Stories shared

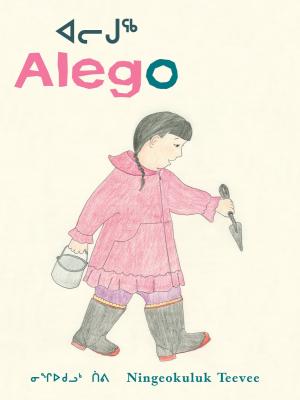

The latest in a long line of groundbreaking women Inuit artists, we spoke with Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona about her own journey into art.

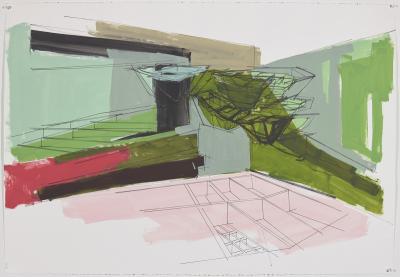

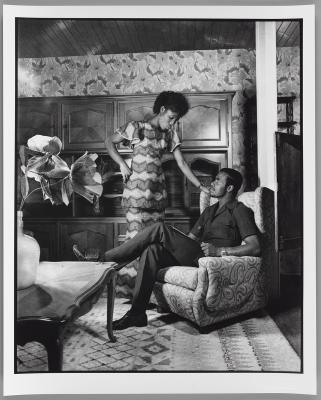

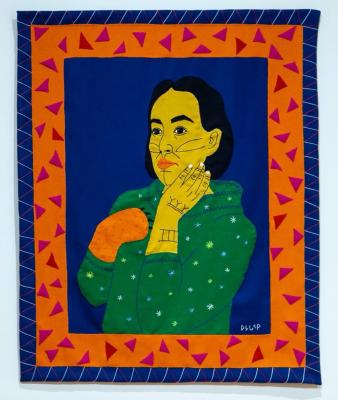

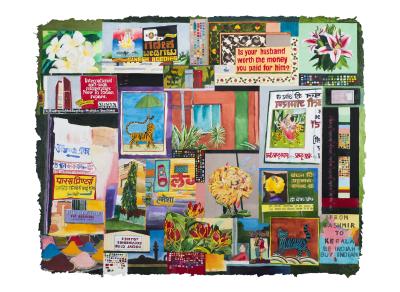

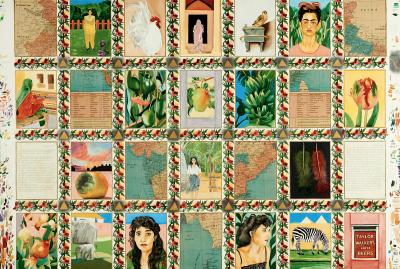

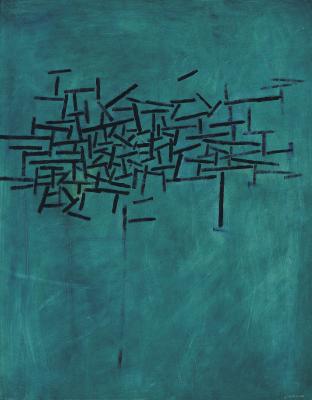

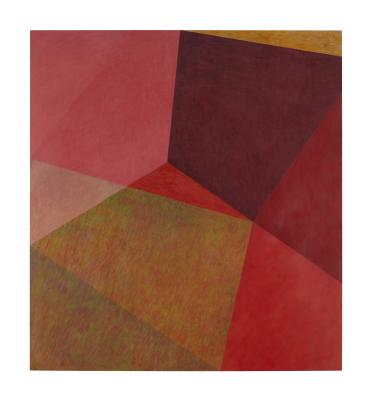

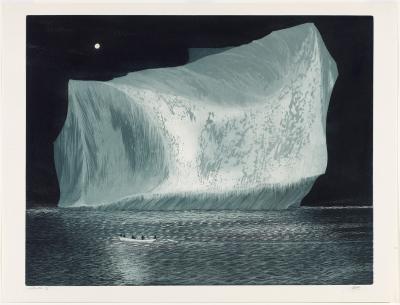

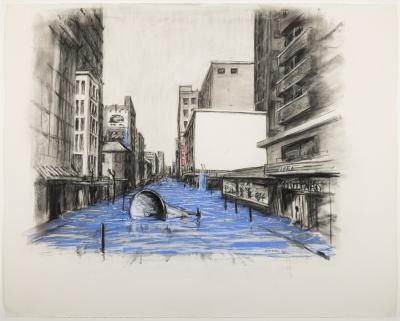

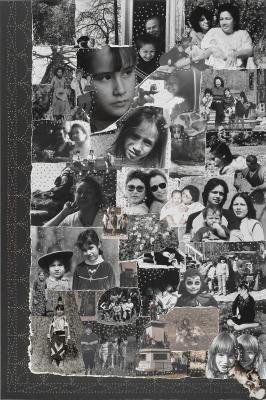

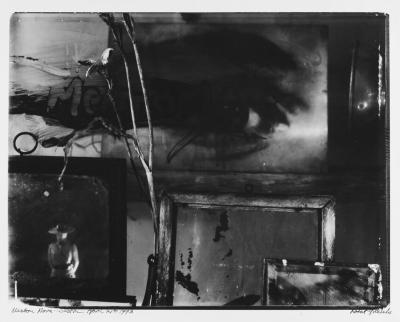

Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona, Tiriganiaq, (2022). Photo courtesy the artist.

One of the most prolific Inuit artists of her generation, the late Victoria Mamnguqsualuk (1930−2016) brought the stories of Inuit superhero Qiviuq (Kiviuq) to life in ink, coloured pencil and tapestries. In 2022, the AGO revisited her monumental creativity with an installation of 17 works on paper. In her portraits of Inuk life, there are communities of people, animals and beings from the spirit world, working together. In every image, a rich story unfolds.

Today, the family's artistic lineage continues in the work of Victoria’s granddaughter, the Ottawa-based artist Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona. We spoke with Gayle about exhibiting alongside her grandmother at the Art Gallery of Guelph and her summers growing up in Qamani`tuaq (Baker Lake), Nunavut.

Foyer: Growing up, were you inspired by seeing your grandmother at work as an artist?

Uyagaqi Kabloona: I grew up in B.C., but often spent summers with my dad and grandmother in Baker Lake. She only spoke Inuktitut and I only spoke English, so all conversation was mediated by dad, but he told me all the same stories that she had told him. What strikes me now, as I pursue my own artistic career, is how art never seemed like a career choice for her − just another thing she did. She would do her day-to-day errands and come hunting with us and there in the corner, she had a pile of half-sewn appliques. She would make these, and parkas for her family, in the same corner she would make giant wall hangings for museums.

Understanding now art as being part of life − it may look like errands, but each trip to the post office is progress − I’ve become acutely aware of the many inequities that surround Inuit art. I think a lot about how there’s an enormous wall hanging in the National Art Centre in Ottawa, a giant tapestry made by my great-grandmother Jessie Oonark, that was so big, it couldn’t be laid out in her house. She had to make it in small pieces and sew them together, the finished piece unseen. Her talent was huge, to be able to compose a scene without looking at the whole piece.

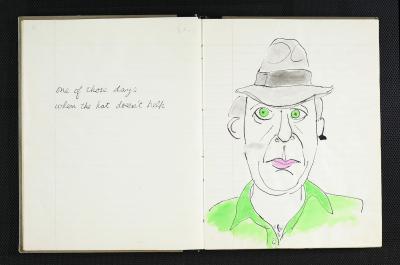

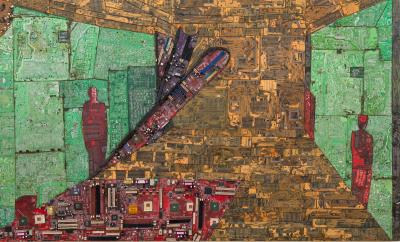

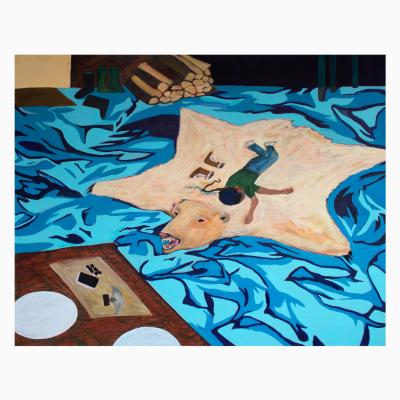

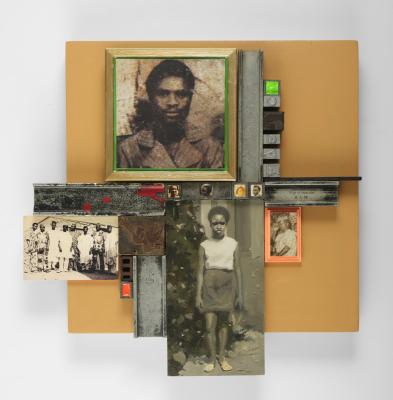

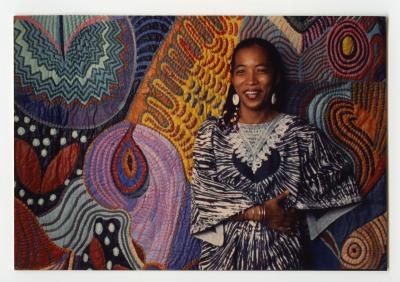

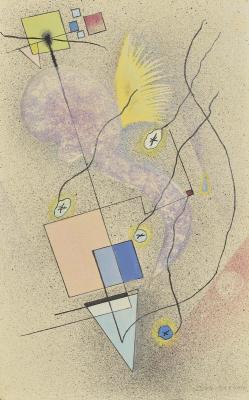

Victoria Mamnguqsualuk. Killing Snake, date unknown. Coloured crayon/pastel and graphite on paper, Sheet: 59.5 × 79.7 cm. Gift of Samuel and Esther Sarick, Toronto, 2002. © Public Trustee for Nunavut. Estate of Victoria Mamnguqsualuk. 2002/10371

Foyer: As part of the Creative Research Residency you recently did with the Art Gallery of Guelph, you spent time with their collection of artworks by your grandmother. What was it like to see her work in that setting?

Uyagaqi Kabloona: It was incredible. I had never seen the artworks they had there. I have a few pieces and my sister and my dad do as well − so I’ve seen a lot of them. The biggest difference was seeing them in an institutional context − to see how far her work has reached and its important place in Canadian art. What I have the most familiarity with are the smaller applique pieces. As part of the Art Gallery of Guelph’s exhibition, Kajuhiutihimajatka | Qautamaat, Taqralik Partridge, the curator, installed two parkas my grandmother made for me. To see those installed alongside artworks by her and my great-grandmother and my aunt and so many incredible Inuit artists, was revelatory. She put the same level of skill and care into those parkas as she did anything she ever sold.

Foyer: You created a wall hanging, titled Tiriganiaq, that was first exhibited as part of that same exhibition. What inspired your choice of subject?

Uyagaqi Kabloona: It wasn’t until that residency that I had the opportunity, and the support and time necessary, to learn how to create something bigger. Only now, as an adult, have I realized the violence behind many of these traditional Inuit stories. So when presented the opportunity to make my own wall hanging, I wanted to engage with the traditional stories, but in a way that shone a light on the gender inequalities. The artwork I made is rooted in the legends of Qiviuq and his many wives. One of those wives was a fox woman, a woman capable of transforming back and forth between animal and human form. It’s a violent story and I wanted to see her for herself, and to liberate her from victimhood, so I took the opportunity with Tiriganiaq to present her alone, in her own space, as the main character of her own story.

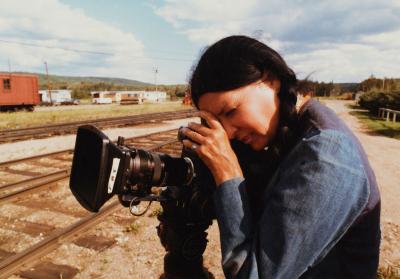

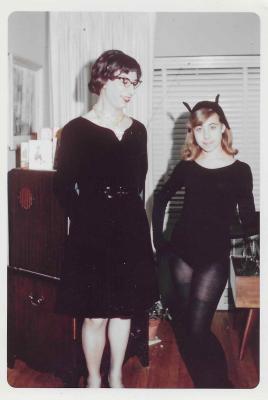

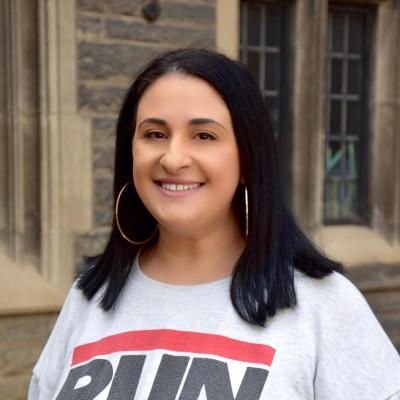

Gayle Uyagaqi Kabloona and Tiriganiaq, (2022). Photo by of Taqralik Partridge.

Foyer: For all the family history, art is your second career. How did that happen?

Uyagaqi Kabloona: Growing up I was encouraged to do something practical, that I could support myself with. So after several years doing environmental policy work in Nunavut, I became an urban planner. But the development review process was too dull, too bureaucratic, and I left it behind for art.

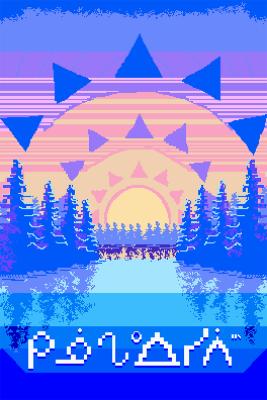

Foyer: Clearly to our benefit. In addition to the exhibition at Guelph, you had a stamp issued by Canada Post this year and Google has acquired your designs. Tell me about the stamp.

Uyagaqi Kabloona: The stamp was one of four by Indigenous artists released on September 30, to commemorate National Truth and Reconciliation Day. It’s a linocut print of an Inuk woman in traditional dress lighting a qulliq, a traditional stone lamp. I had a lot of anger towards the idea of Truth and Reconciliation. I feel the truth needs to be heard first, and reconciliation is far from us. But I didn’t want to make something pessimistic. To be truthful to myself, I had to remove the settler aspect and focus entirely on what it means to be Inuk. Growing up, I had never saw a qulliq lit − many of the traditions had been put aside − but I’ve since learned to light it myself. I see the lamp as a symbol of continuing culture, as a practical expression of daily life, and wanted to communicate that in order to continue as a people, we need to keep doing what we have always done, which is continue.

This interview has been condensed and edited for space.