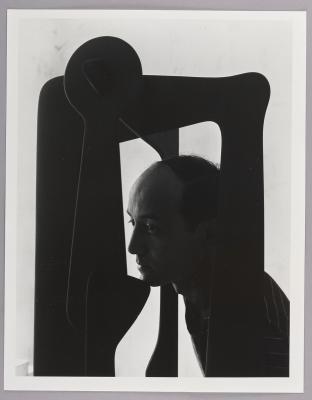

Family ties with Pio Abad

The contemporary artist and nephew of Pacita Abad reflects on his aunt’s legacy

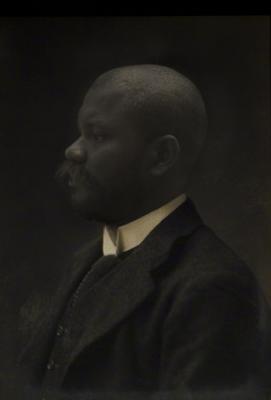

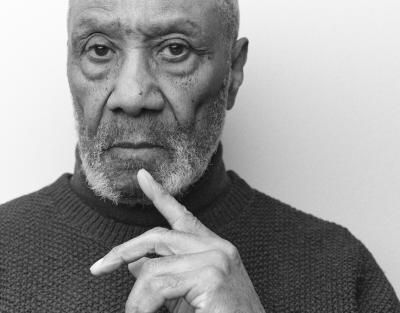

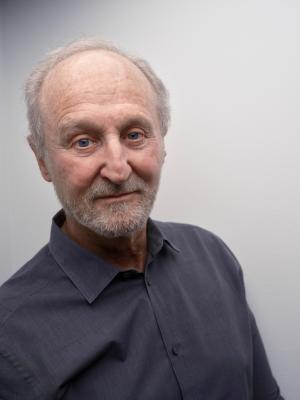

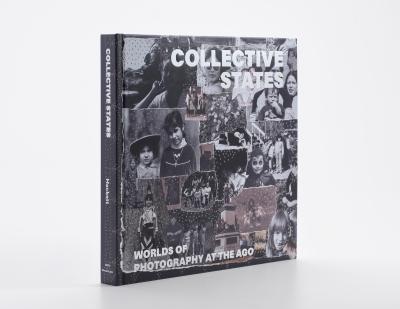

Photo by Frances Wadsworth Jones

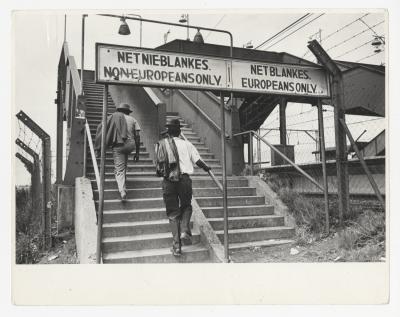

In Pacita Abad’s family, art and politics are inextricably linked. After working as a student activist in her hometown of Manila, 24-year-old Abad was forced to flee the Philippines in 1970, escaping the violent regime of President Ferdinand Marcos. This event marked a pivotal moment in her life, significantly informing the ethos of her art practice.

Roughly a decade later, during the Marcos regime’s final years, her nephew Pio Abad was born. Spending his teenage years idolizing the globetrotting, artistic journey of his aunt, Pio was inspired by Pacita to leave Manila as well, in pursuit of his own career in the arts. Fast forward to 2024, and Pio is now an internationally acclaimed artist, continuing to curate his late aunt’s work and championing her legacy.

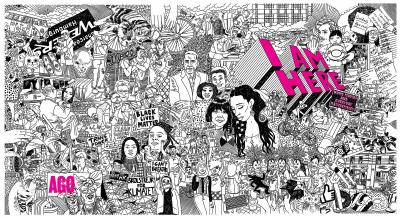

To celebrate the landmark exhibition, Pacita Abad, Pio recently appeared at the AGO for a roundtable discussion with the exhibition’s curators Victoria Sung, Matthew Villar Miranda and Renée van der Avoird. The group explored Pacita’s work and life, providing candid insights into the exhibition.

Pio’s expansive practice includes drawing, painting, textiles and installation. His work critically examines historical events, offering counternarratives that show complicity between incidents, ideologies, and people. Nominated for the 2024 Turner Prize, his exhibition, currently on view at Tate Britain, includes drawings of Benin bronzes, reflecting on the 1897 British invasion of the West African nation through a personal lens. While their technical approaches may differ, the spirit of Pio’s practice echoes that of his aunt, driven by the narratives of oppressed and colonized people of colour worldwide.

Pio spoke to Foyer about family, migration, politics, and his treasured relationship with the work and legacy of Pacita Abad.

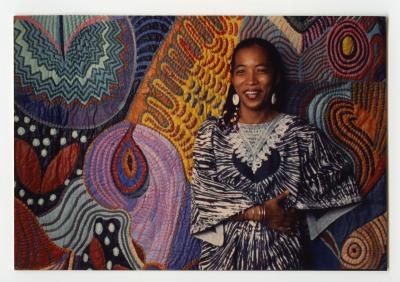

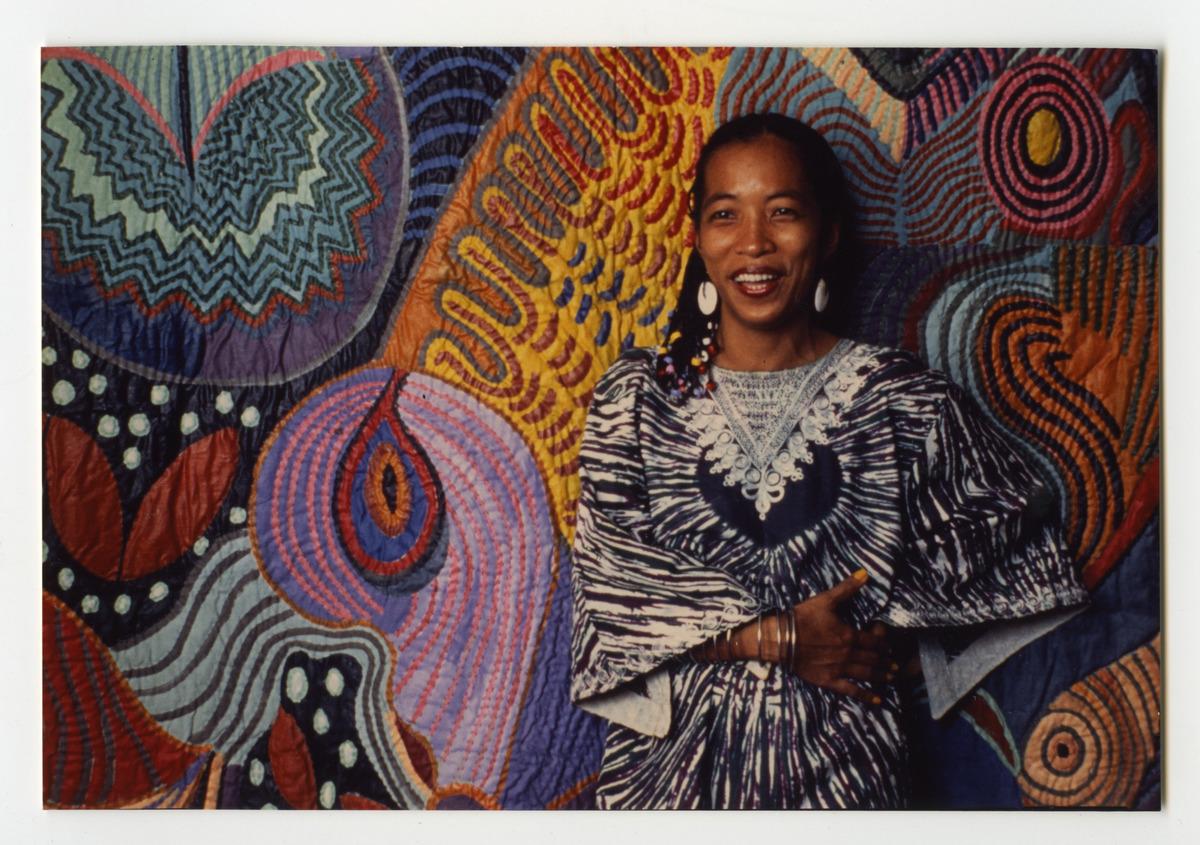

Pacita Abad with her trapunto painting Ati-Atihan (1983) wearing garments and jewelry collected on her travels. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate.

Foyer: You've spent your life engaging with Pacita’s legacy and curated several exhibitions of her work. Could you describe what it felt like for you the first time you saw this full retrospective exhibition in person?

Abad: This is a show that's traveled to four different cities, and I feel like every time I see the exhibition, I see it for the first time. Pacita's work is so epic and bursting with everything - with narrative, with color, with material - that it's almost always difficult to contain it.

When I saw the first iteration of it at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, I was incredibly emotional. I realized that not even she had the privilege of seeing her work laid out on this scale. She worked intensely over a period of three decades, she was always making. It's a tragedy that she passed away before her work was fully appreciated. Initially, there was a hint of sadness in realizing that we were experiencing something that she never did. Then that was immediately superseded by seeing how people look at the work. One of the pleasures of curating various exhibitions of Pacita’s work over the years is watching people look at the work. They often sit down in front of it and almost treat it like a film, taking on the textures and the details. There's something beautiful about that because it doesn't happen anymore in this day and age when people don't have much of an attention span. Her work captivates, in every sense of that word.

Her work is generous, so it invites the viewer to be generous as well. The AGO iteration of this exhibition is probably the second largest, and it's amazing to be able to get to see the work in this scale again. Also, there are exhibition labels in Tagalog here, and I don't think labels and most museums in the Philippines are even in Tagalog. For her work to take up space, but also for the Filipino language to take up space, really means a lot.

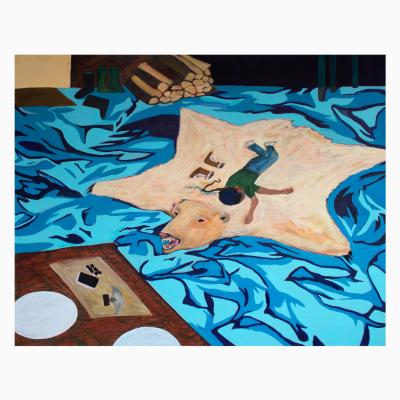

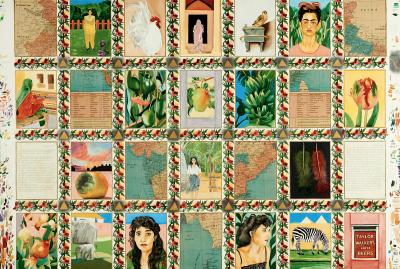

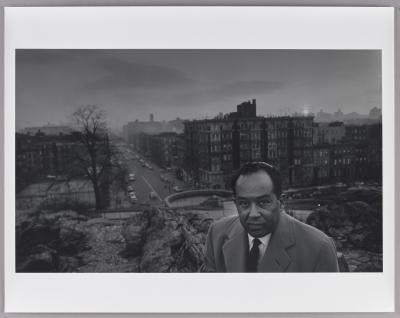

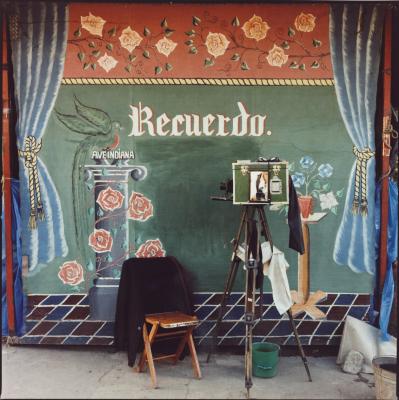

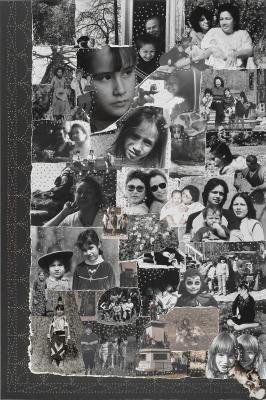

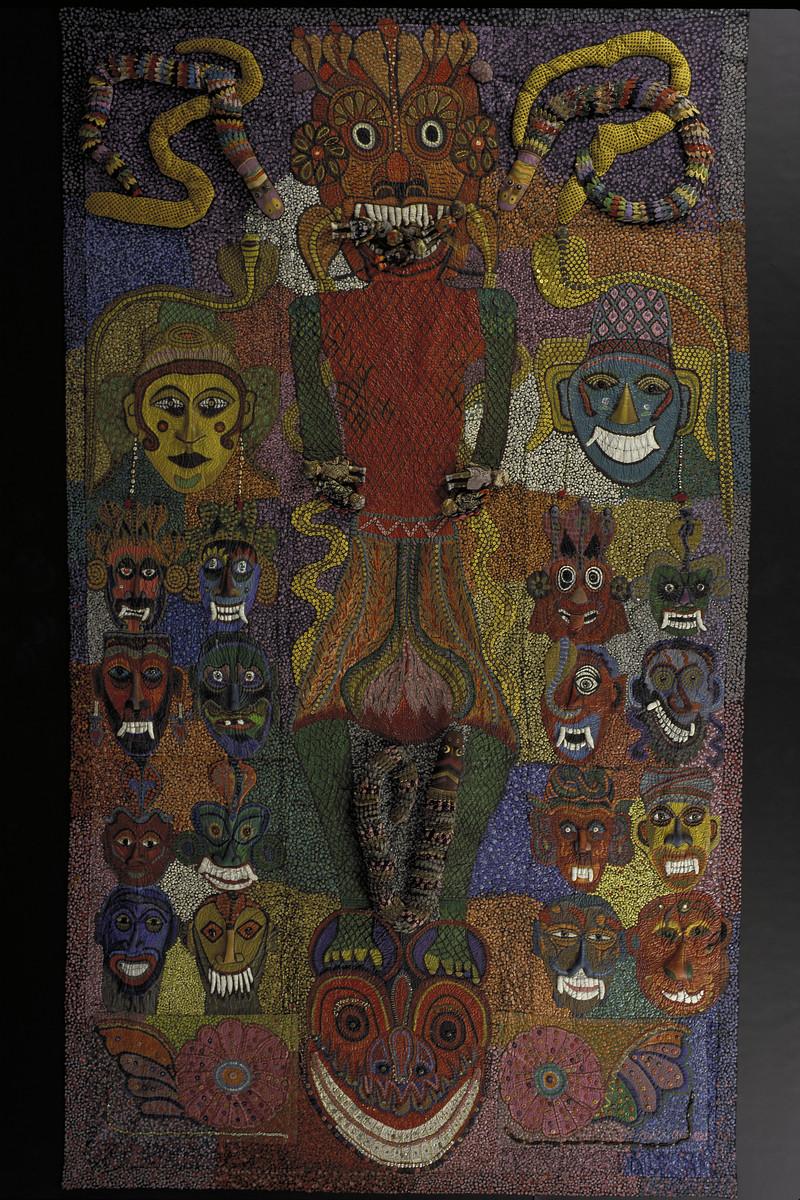

Pacita Abad. Marcos and his Cronies, 1985-1995. Mixed-media painting. Collection Singapore Art Museum. Courtesy Pacita Abad Estate and Singapore Art Museum. The copyright of this artwork belongs to the artist or their authorized representatives and may not be reproduced for any purpose whatsoever without the prior written permission of the Singapore Art Museum/National Heritage Board and/or copyright owners.

Leaving the Philippines during the Marcos regime was a pivotal moment in Pacita’s life and seems to have set the tone for a lot of the themes and commentary throughout her body of work. You were born in Manila during the end of the regime, leaving in 2004 at the age of 21. Could you share how these events have helped shape your approach to your practice?

It's one of those strange moments of timing. I left the Philippines in September 2004 to pursue my studies in the UK, and Pacita died in December that same year. The last time I saw her, she had just opened her final exhibition in the Philippines, literally a few days before I boarded my flight. She had such a big influence on me. I remember she told me, “If you want to be an artist, you need to get the fuck out of Manila.” I think, for her, it was important to be embedded in the stories of the Philippines and the issues that affect Filipino lives, but it was also important to see this through other lenses and relate her perspective to the experiences of other colonized people throughout the world.

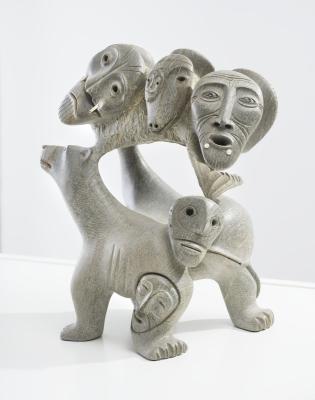

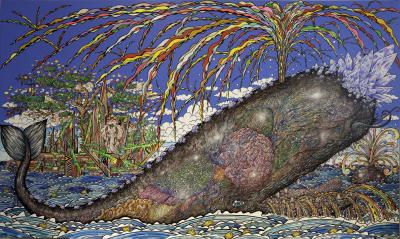

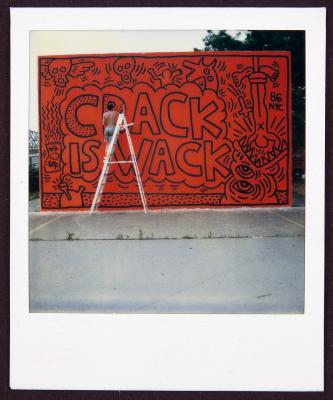

Thinking back to the history of the Marcos dictatorship and how it was formative for our family, Pacita fled in 1970 because her activities as a student activist made things quite perilous for her. What I love about this exhibition is the first work you see when you enter the space is this 16-foot-high trapunto of demons on top of demons, eating children, surrounded by snakes - which to me is her masterpiece and manifesto. When you describe it like that it sounds absolutely horrific - and it is - but it's also frightening, beautiful, exquisite and sublime. That painting is called Marcos and his Cronies.

Part of Pacita’s genius is how she uses different cultures, cultural heritages and materials to speak to each other. In this work she used the tradition of Sri Lankan masks to talk about the history of corruption in the Philippines. There's this constant need to refract her experiences - and the Filipino experience - through the lenses of other traditions. Now that the Marcoses are back in power in the Philippines, this work becomes something else. It's not only about something from the past, but it's about a past that is very much present.

Though my work as an artist is very different, I use the language of visual form to talk about histories of oppression and corruption, that are not just my experiences, but a larger group of people. Pacita’s work has certainly affected not just how I view art, but how I view life. I always think that Pacita’s work, while being these incredibly beautiful paintings, also has such a strong journalistic intent. You can really see her capturing the day-to-day lives of people that she's coming across. There's such a burning desire to talk about the plight of others and to situate herself within those experiences. I think, growing up in my family - which is either very artistic, very political, or often both - that desire has become part of our genetic code.

From drawing to sculpture to installation, your work incorporates an array of mediums. When you conceive of an idea for a new artwork, how would you describe your process for narrowing down a technical approach and deciding what materials and mediums to utilize?

It changes depending on the situation. My work is less monumental than Pacita’s, but it's more materially promiscuous. Everything starts with research and looking at the archive. For me, it comes down to what medium is best to tell the story. Often, I start with drawing. I make these really intricate pen and ink drawings that almost map out the stories that I want to tell. And sometimes, drawings become insufficient because the viewer needs to be confronted with something, so a drawing needs to be transformed into a piece of 3D printed jewelry, a monumental concrete sculpture, or some wall text. It's about storytelling and deciding how best to reach people and how best to bring a story to life. Thinking about my relationship to curating Pacita’s work over the past few years, I also see it as one vast archive that I navigate. It just so happens that the archive is made up of four by five-meter paintings of sharks fighting octopuses. There's still that sense of looking through historical material and finding the best way to tell the different stories contained within.

More recently, I've been interested in materials that speak directly to the weight of history, like bronze, concrete and marble. My work deals with histories that have often been forgotten or conveniently set aside. So, to transform the stories into bronze and marble seems to be a way to make them even more present than they've ever been or ever will be.

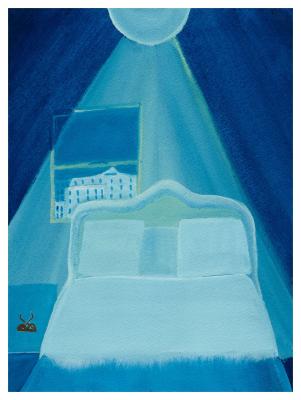

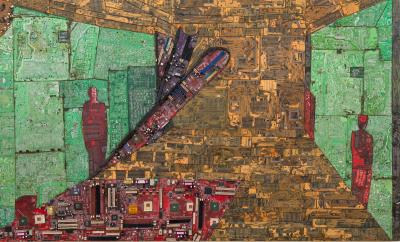

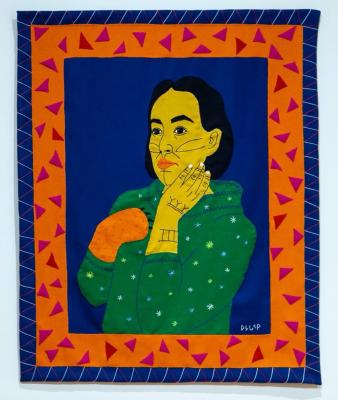

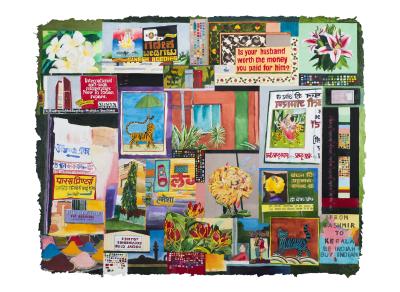

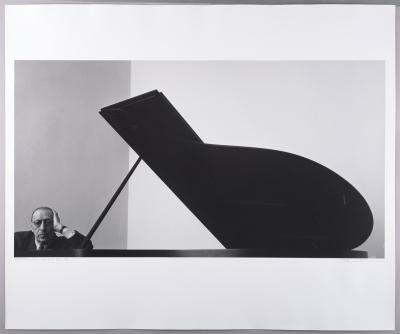

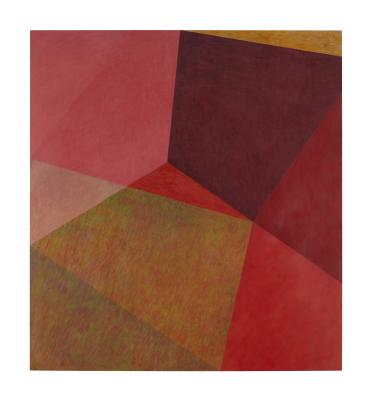

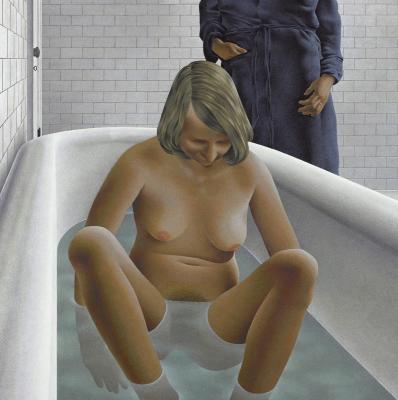

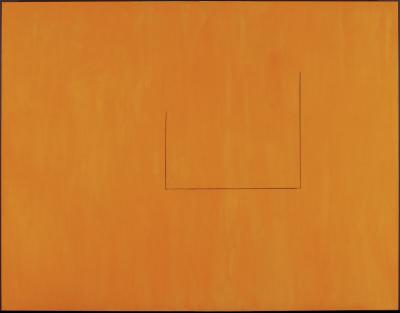

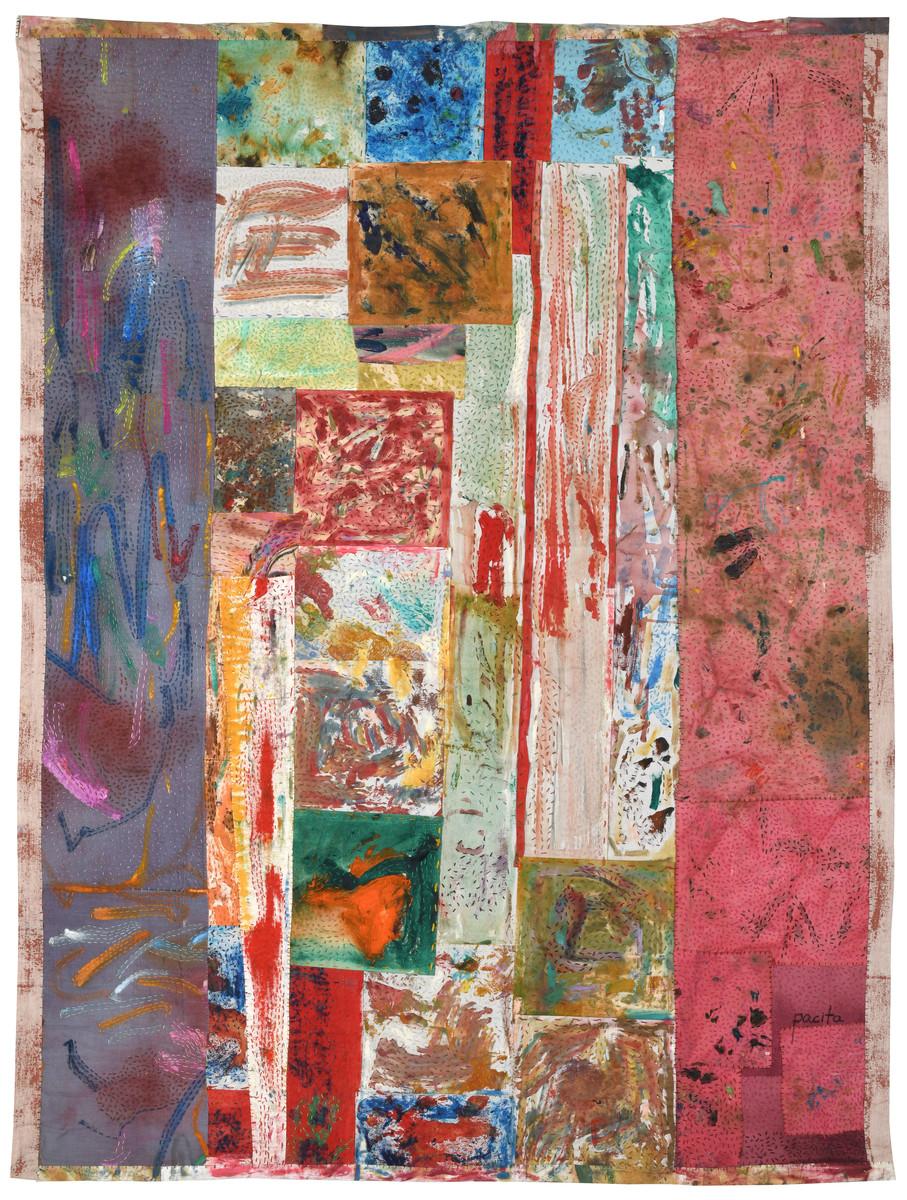

Pacita Abad. White Heightens the Awareness of the Senses, 1998. Oil, acrylic, oil pastel, dyed cotton, painted canvas, painted cloth on stitched canvas. Courtesy of Pacita Abad Art Estate. © Pacita Abad Art Estate LLC.

There are over 100 of Pacita’s works in this show. Is there one that comes to mind, that perhaps you’d like to draw more attention to or speak about in depth?

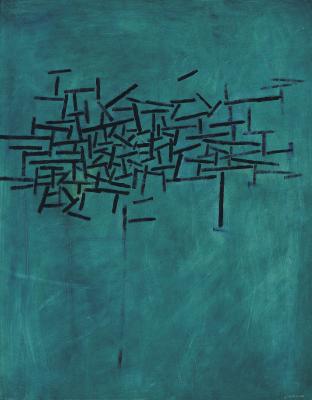

One of the things I really love about this particular presentation is that one of my favorite abstract paintings of hers is given this space where viewers can see both sides of it. And actually, when I started curating Pacita’s shows, that's something that I insisted on - to be able to show the intensity of the painting in the front, but then also in the back, you see how intricately constructed they are. It makes the viewing experience all the more powerful.

This particular work is an abstract work called White Heightens an Awareness of the Senses. For Pacita, abstraction isn't about the absence of subject matter, it's actually about the abundance of it. I'm thinking about that title in relation to the recent US election. In the panel text, for the first iteration of the exhibition at The Walker, there was a Zora Neale Hurston quote that read, “I feel most coloured when I am thrown against a sharp white background.” Pacita was a genius at titling work.

This work is really gestural in terms of brush strokes but, then you see as you get closer, she followed the brush strokes with embroidery. So, formally, it's an incredible work. In terms of what it's trying to say through abstraction, it seems like it could have been made today. I always talk about Pacita’s abstractions as a kind of archive of the experiences of the lives of people of colour. Fabric is the armature for these compositions, and fabric is never neutral - it's from the day to day lives of people. It has history. It's about struggle. It's about domesticity, but also the politics within that.

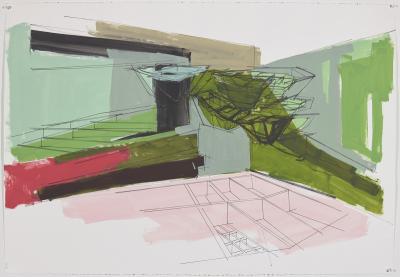

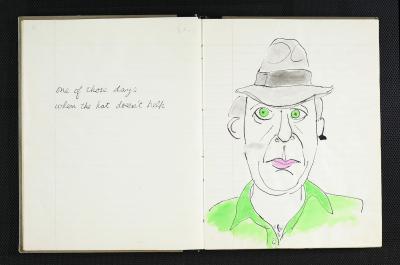

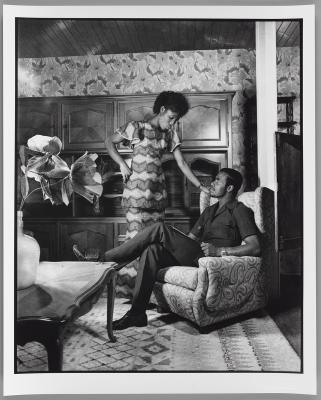

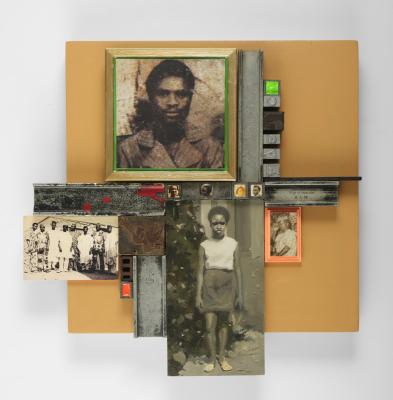

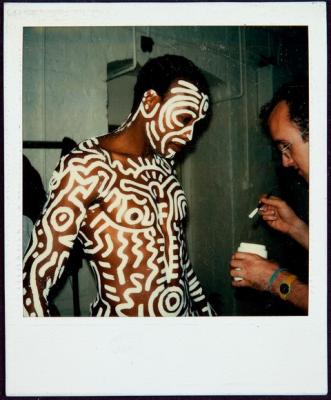

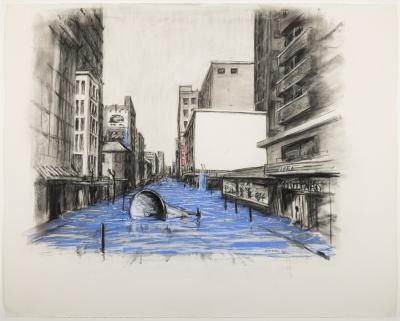

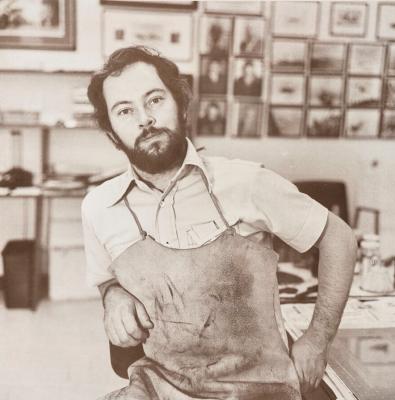

Pio Abad, 1897.76.36.18.6 No. 23, 2024, India ink on heritage woodfree paper, 1016 x 686 mm. Photo: Andy Keate. Image courtesy of the artist.

Is there an artwork, body of work, or a project of some sort that you're currently working on - or recently finished - that you're excited to share with people?

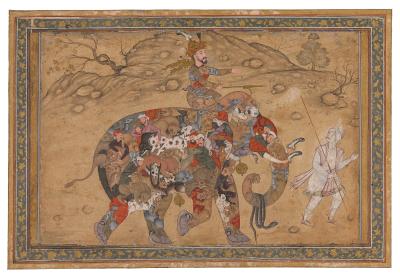

There's a work that is part of my show currently on view at Tate Britain. It's the first time I've been able to show drawings in London. The series of drawings that depict historical Benin bronzes on one side and on the other side are stacks of domestic objects that I have at home. This body of work came from me realizing that my home in London was actually the exact site where the British Army gathered their weapons and prepared ammunition on their way to looting and ransacking Benin in 1897. Going back to this idea of home being the site of politics, it can't be more direct than this example. I drew the Benin bronzes because they have become these icons of colonial violence, but each object carries a specific history. So, I drew them to the exact scale that they are in real life, and then stacked household objects on the other side, measuring them according to my own personal and emotional dimensions. It's a project I'm carrying on, and it's exciting because it expands the narrative of my work beyond the Philippines, but still very much home.

It also resonates back to Pacita as well. For her, all these artifacts we see in museums are not neutral objects. They meant things to families. They were ritual objects in domestic places, before they were in these sanitized museum spaces. They're ghosts of people's lives, and it's good to not present them as hauntings, but rather something that is still very relevant today.

Pacita Abad is on view now until January 19 on Level 2 in the Sam & Ayala Zacks Pavilions (galleries 244 and 245) at the AGO. Organized by the Walker Art Center in collaboration with Abad’s estate, the exhibition is curated by Victoria Sung, Phyllis C. Wattis Senior Curator at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), and former associate curator, Visual Arts, Walker Art Center; with Matthew Villar Miranda, curatorial associate at BAMPFA, and former curatorial fellow, Visual Arts, Walker Art Center. The AGO presentation is organized by Renée van der Avoird, Associate Curator, Canadian Art.