Four Brazilian Artists on View at the AGO

These artists used modern art to respond to Brazil’s diverse and changing sociopolitical climate

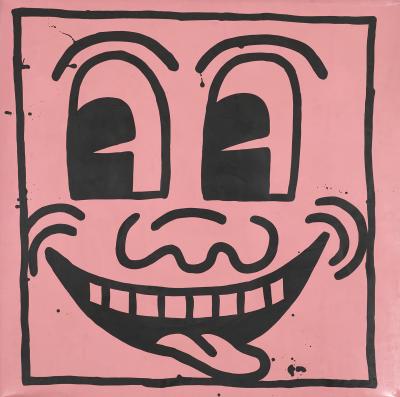

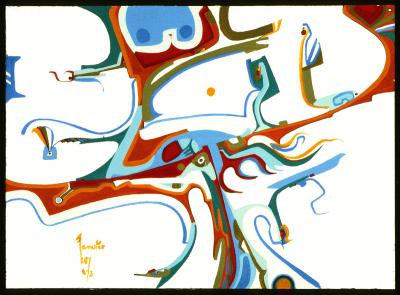

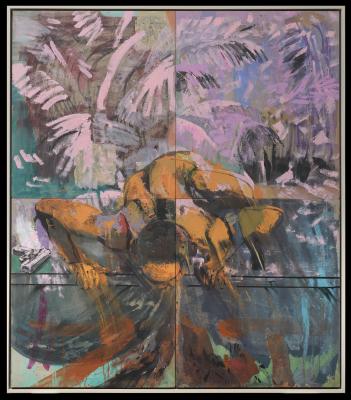

Osmar Dillon. Sun/Shadow, 1973. Acrylic on painted fibreboard with plexiglas,100.3 x 100.3 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of Brascan Limited, 1976. © Estate of Osmar Dillon, courtesy Tramas Galeria de Arte. 76/180

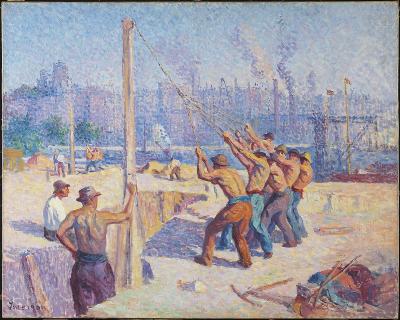

Brazil in the 1950s and 1960s was a time of sociopolitical change. The 1950s focused heavily on modernization and industrialization. In 1960, Brasilia, a utopian modernist city built from scratch, replaced Rio de Janeiro as the country’s capital. Political tension in the 1950s (and even earlier) paved the way for a military dictatorship over the country from 1964 to 1985.

In response to Brazil’s changing socio-political climate, two modern art movements began to develop: Concretism and Neo-Concretism. Both movements focused on mechanized forms and optical illusions and prevailed in Latin America in the 1950s. In Brazil, the Concrete Art Movement is associated with São Paulo and focused on being rational and systemic – a response to Brazil’s increased industrialization. Neo-Concrete art, which is associated with Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, was a response to the Concrete movement, advocating for adding human experience and a poetic approach to abstract art and rejecting the cold objectivity of Concretism.

Four Brazilian modern artists are on view at the AGO as part of the exhibition Moments in Modernism. These artists represent the distinct ways Brazilian artists engaged with modern art and how they used it to grapple with the complexities of identity in a diverse national landscape. The Concrete and Neo-Concrete movements influenced some of these artists, while others completely rejected them for their own unique practices.

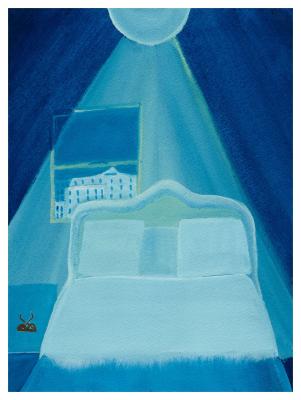

Osmar Dillon

Osmar Dillon, New Moon, 1973. Acrylic on fibreboard with plexiglas, 100.3 x 100.3 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of Brascan Limited, 1976. © Estate of Osmar Dillon, courtesy Tramas Galeria de Arte. 76/179

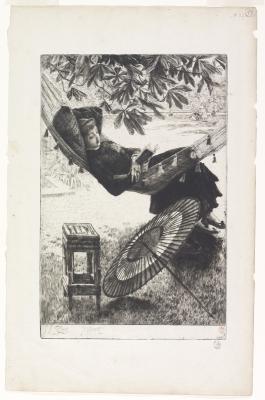

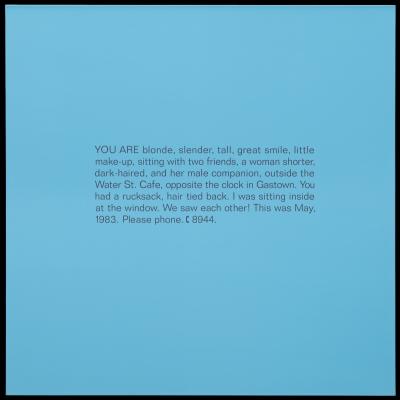

While he first studied architecture, Osmar Dillon (1920 - 2013) devoted his life to painting and poetry. In 1960, he began combining the two, resulting in a series of short poems playing with the usage of blank space. Seeking the integration of poetry and painting, a key aspect of his practice was incorporating words and language, both an ornamental and an intrinsic part of his works. Another key aspect of Dillon’s practice is the viewer’s participation. You may notice in Rain (1973) that the materials reflect the viewer, incorporating them into the work. The way Dillon involves the spectator goes beyond playful; the combination of words and abstract forms calls upon the viewer to creatively reconstruct new meanings of his work. His poetic approach to art naturally led him to join the Neo-Concrete movement, allowing him to focus on both the materiality of his work and how the viewer consumed it.

Osmar Dillon, Rain, 1973. Plexiglas, stainless steel, wood, 100.3 x 100.3 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of Brascan Limited, 1976. © Estate of Osmar Dillon, courtesy Tramas Galeria de Arte. 76/178

While Dillon lived a discreet life (hence his elusive digital footprint), it’s been recorded that he partook in Domingos de Criação (Creation Sundays in English), a series of experimental public events hosted by the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro in 1971. Taking place in the museum’s outdoor spaces, Domingos de Criação aimed to expand the public meaning of art in the landscape of Brazil’s military dictatorship. The series occurred over six Sundays, with Dillon participating in the Down to Earth Sunday, where the artists worked with donated sand, lime, cement, gravel, clay, and mud.

Paulo Roberto Leal

Aiming to expand the concept, Paulo Roberto Leal (1946 - 1991) was known for “painting” without any of the typical tools. The artist swapped paint and brushes for paper, milky acrylics, and sewing machines. He often worked with the canvases by cutting and pasting, sewing, and dyeing them with oil.

Like Dillon, Leal did not begin his career as an artist. He studied economics during university and worked at the Central Bank of Brazil for years. Without any formal training, he learned about art by meeting artists, as well as attending exhibitions and visiting studios. Leal acquired a small collection of art created by artists associated with the Concrete and Neo-Concrete movements, such as Ivan Serpa and Lygia Clark.

Installation view, Moments in Modernism, June 14, 2024 - March, 2026. Art Gallery of Ontario. Works shown: Tomie Ohtake, Opus 3, 1973; Osmar Dillon, New Moon and Sun/Shadow, 1973. © the artists. Photo: AGO.

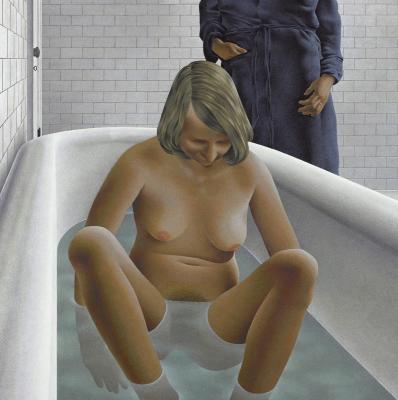

Starting his artistic career in the late 1960s, Leal also became associated with these movements. His work incorporated geometry, emptiness, interstices, and silence, and his prime focus was on the materiality of his work. On view as part of Moments in Modernism, Image 21 (1973) represents how Leal often used paper in his practice. In this work, squares of white paper are geometrically ordered and enclosed by a translucent white acrylic sheet. The sheets of paper are curled, a natural reaction that happened over time. Leal’s use of milky acrylic creates an ephemeral and sensual atmosphere that contrasted with the chaos of the military dictatorship happening in Brazil at the time.

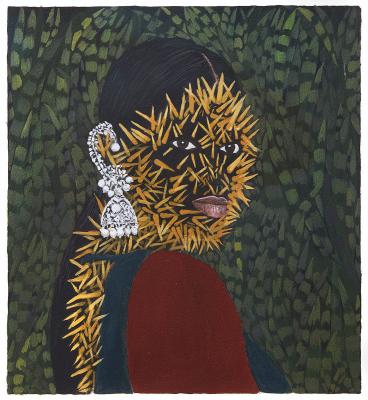

Rubem Valentim

Like the other Brazilian artists on view in Moments of Modernism, Rubem Valentim (1922 -1991) also did not start as an artist. He trained as a dentist and journalist before he left his dental career in 1948 to become a self-taught artist.

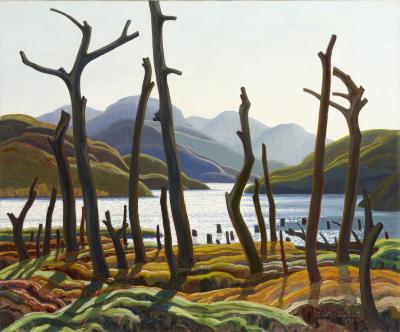

Installation view, Moments in Modernism, June 14, 2024 - March, 2026. Art Gallery of Ontario. Works shown: Osmar Dillon, Sun/Shadow, 1973; Rain, 1973. © Estate of Osmar Dillon, courtesy Tramas Galeria de Arte. Photo: AGO.

Valentim’s work is an homage to Afro-Brazilian culture. His work incorporates Afro-diasporic aesthetics, often focusing on Orishas, which are spiritual deities found in religions across the African diaspora. Enslaved people from Africa brought these religions to Brazil during the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade. In his work, Valentim abstracts religious symbols to represent these spirits, using hard-edged lines, circles, cubes, and arrows while incorporating bold and flat colours. While Valentim was not formally associated with them, his work includes comparable aspects to the Concrete and Neo-Concrete movements. Valentim mainly focused on creating a visual language for Afro-Brazilian culture.

Tomie Ohtake

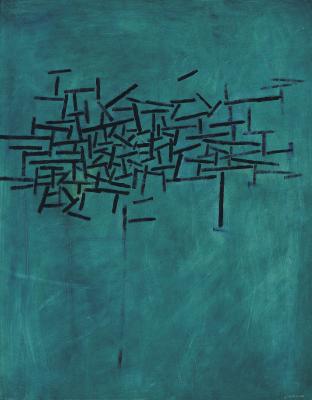

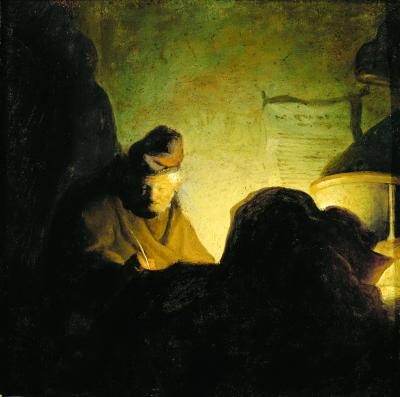

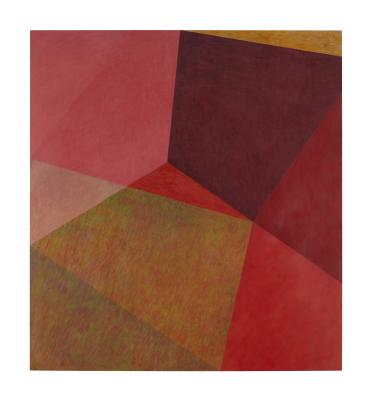

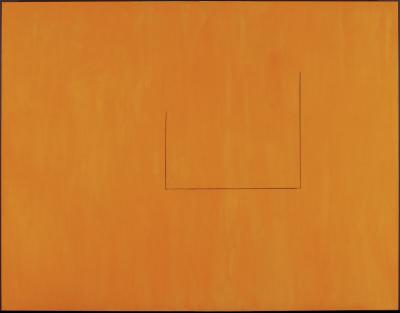

Tomie Ohtake. Opus 3, 1973. Oil on canvas,165.1 x 165.1 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of Brascan Limited, 1976. © Instituto Tomie Ohtake. 76/184

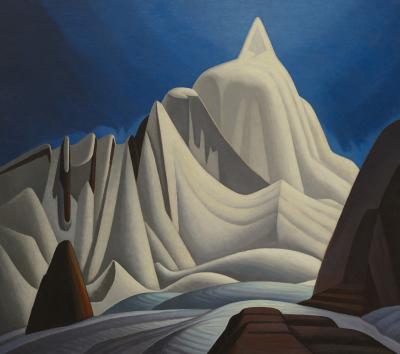

Unlike the other Brazilian artists in Moments in Modernism, Tomie Ohtake (1913 - 2015) blatantly rejected the Concrete and Neo-Concrete movements, preferring to develop her unique abstract style. Born in Kyoto, Japan, Ohtake settled in São Paulo after she could not return home from a trip visiting family due to the Second Sino-Japanese War. Ohtake began painting at 39 and became one of Brazil’s most influential abstract artists.

Ohtake’s practice was experimental, and she did not want to be confined to a formal art movement. She ripped and cut paper to create tiny collages that would inspire her paintings and even painted blindfolded. She often avoided naming her works to prevent limiting their interpretation.

Ohtake also used spray guns in her work, as seen in Opus 3 (1973), which is on view in Moments in Modernism. She built layers of paint in her work, creating texture and luminous colour. She was also a very skilled colourist – if you look closely, there is a very subtle difference between the reds used in Opus 3.

Ohtake passed away at 101 in 2015. Her influence can be seen all over Brazil through the public sculptures she created, as well as through Instituto Tomie Ohtake, a not-for-profit cultural centre built in São Paulo to honour her legacy.

Experience a sample of Brazilian modern art by visiting Moments in Modernism, on view on Level 4 as part of Moments in Modernism at the AGO. The exhibition is co-curated by Debbie Johnsen, Assistant Curator, Contemporary Art, and Stephan Jost, Michael and Sonja Koerner Director, and CEO. Moments in Modernism features work that will form the cornerstone for the expansion of the new Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery. The new building is being designed by architects Diamond Schmitt, Selldorf Architects and Two Row Architect to showcase the AGO's growing collection of modern and contemporary art.

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)