Queering St. Ives

Dr. Ian Massey discusses the St. Ives artist colony and what might have enticed Helen McNicoll

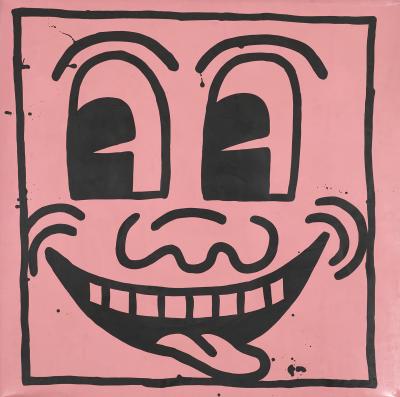

Unknown photographer, Helen McNicoll in her studio at St. Ives, c. 1906. Gelatin silver print, 24.3 x 13.9 cm. Courtesy of The Robert McLaughlin Gallery Archives.

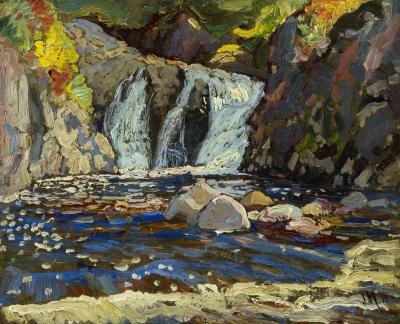

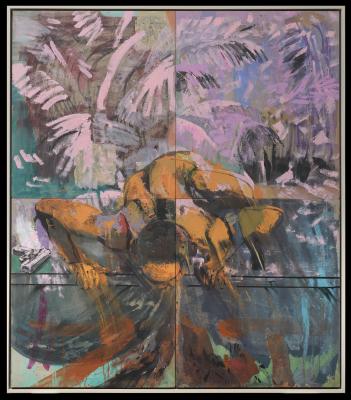

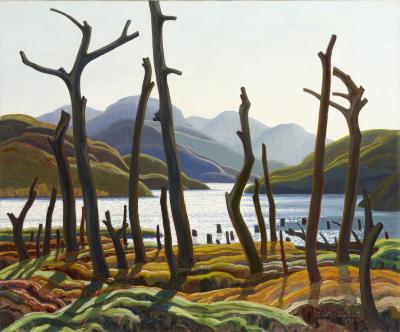

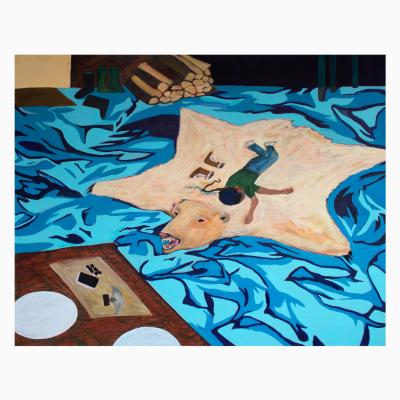

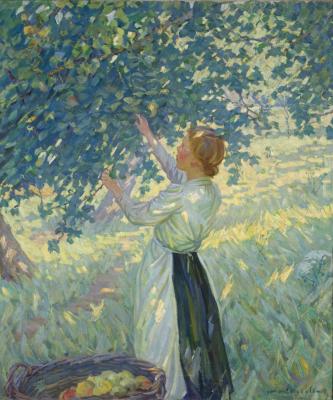

One of the many delights that await visitors to Cassatt – McNicoll: Impressionists Between Worlds, is the opportunity to take a closer look at the art and career of Canada’s own Helen McNicoll. An under-recognized art star, her luminous paintings of women and children showcase a skillful appreciation for open spaces and azure skies, the likes of which we so rarely see here in Canada. That the bulk of her all-to-short career was spent in Europe, at a time when artistic professionalism demanded European education and exposure, is no surprise. But what does stand out to the casual viewer, is her decision in 1905 upon graduating from the Slade School of Fine Art, to relocate to Cornwall. Specifically, to St. Ives, a small coastal town.

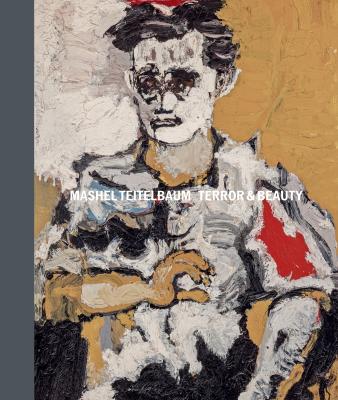

To better understand the appeal of St. Ives and its legacy, we reached out to curator and writer Dr. Ian Massey. Heralded by The Spectator as ‘absorbing and extremely well written”, Massey’s 2022 book Queer St. Ives and Other Stories offers a unique view of St. Ives, weaving together art history, biography and social history to spotlight the town's heyday in the mid-20th century, when it played host to modernists John Milne and Barbara Hepworth.

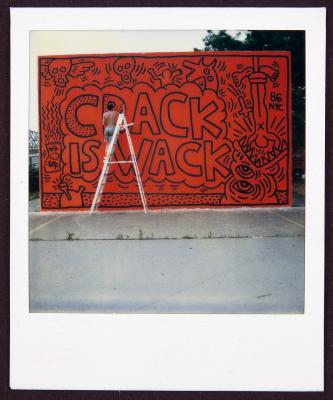

Ian Massey in St. Ives. Photo courtesy Ian Massey.

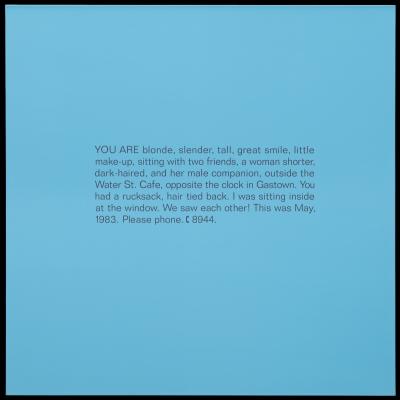

Foyer: We know that McNicoll moved to St. Ives in 1905, to attend the Cornish School of Landscape and Sea Painting, where she would meet fellow artist, advocate and possible romantic partner Dorothea Sharp. Do we know what reputation the school had at that time? Prior to the ‘Cornish renaissance’ of the 1950s, was St. Ives just another beautiful artist colony or something unique?

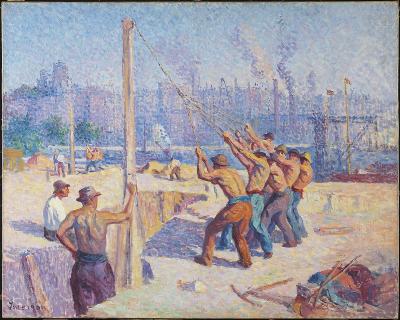

Massey: The town’s reputation as an art colony was established long before the 1950s, though it is true to say that its significance as an internationally recognised hive of modernist production gained great traction during that decade. Up until the latter half of the nineteenth century, Cornwall was difficult to access because of its remote location, but travel to the county became far easier when a railway line linking Plymouth and Truro was opened in 1859, and then subsequently when the line to St Ives opened in 1877. The colony first became established a few years later, and The School of Landscape and Sea Painting that McNicoll attended became renowned not long after it first opened its doors in the 1890s. It drew artists not only from elsewhere in the UK, but internationally, from America, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Along with the physical splendour of land and sea in and around St Ives, its generally benign climate and long daylight hours were also central to the town’s allure, particularly so during the period when plein air painting was fashionable in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Foyer: You say it has long been cliché to remark on the particular clarity and translucency of the light in St. Ives. Indulge us a little – what makes this bit of Cornwall so singular?

Massey: Well, as I have written in my book, the light in St Ives is transformative, certainly in the way it affects colour, notably that of the sea, which takes on hues – aquamarine, mauve, turquoise – that are more redolent of the Mediterranean than the Atlantic. Generations of artists have been drawn to the town because of this defining characteristic of light. There’s also the distinctive geography of the place, its harbour and narrow streets effectively bracketed by Porthmeor and Porthminster, the largest and most beautiful of its four beaches. There’s also a strong romantic attraction, in the elemental wildness of the town’s adjacent coastline, and in that of the nearby moorland, with its pagan mystery of standing stones, and megalithic dolmens. Considered more generally, Cornwall has long provided a haven for nonconformists, a place of self-imposed exile to which one might escape from the rigidity of social expectations. In this respect, the notion of Cornwall as ‘other’ – at once both part of England while at the same time ‘Celtic’ and therefore intrinsically foreign – is fundamental to its appeal.

Foyer: You recount with delight your first visit to St. Ives in 1976, its hold on your imagination and the need for a historical corrective. Was it ‘coincidence, curiosity or crisis’ that led you to expand your study of John Milne to consider St. Ives more broadly?

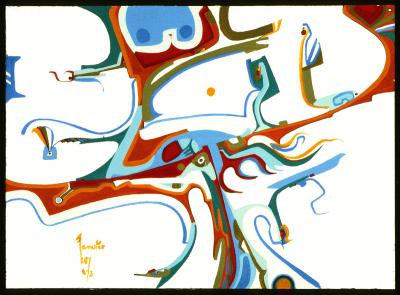

Massey: My original intention was to write a book about the sculptor John Milne, one that considered both his life and his work. Aware of him for many years, I somehow suspected that there was more to his story than had yet been told. I was fascinated by ‘Trewyn House’, where Milne had lived and worked from 1956 until 1978, the year of his death. The house is situated immediately behind Barbara Hepworth’s former home, studio, and garden (what is now the Barbara Hepworth Museum). ‘Trewyn House’ is shielded from view by the high stone walls that surround its garden, making the place all the more mysterious and intriguing for me.

As so often happens, the research led the way and, as it progressed, I came to realize that Milne was a central, and indeed crucial figure in the virtually undocumented queer history of St Ives. And, in writing this history – or at least a substantial part of it – I realized that I was effectively documenting a vital part of the social and cultural history of St Ives for the first time. Therefore, as the research became more expansive, so too did my ideas about what direction my narrative might take, how it might be structured, and what it might encompass. The original premise, of a biography of Milne combined with a critical analysis of his work, remains a significant element of the text, but it is now framed within a far broader context than I had initially imagined.

Foyer: In your book, St. Ives is as much a character as the artists themselves, a place of such translucent light and exotic palm, where in Autumn, ‘one might turn in on oneself, depression seeping in like a sea fog’. Were you to anthropomorphize and typecast St. Ives, what role would you assign it? Tempestuous sibling, stern but loving nanny, generous but distracted mother?

Massey: In response I would say that, depending on season and circumstance, one’s anthropomorphic assignments might prove wildly different! Viewed through the lens of a holidaymaker, the town is deeply alluring, and many of those who visit on holiday fantasize about moving to live there permanently (I have done so myself – though house prices there have long forbidden such a move). For them St Ives might be seen as a rather exotic and comforting maternal figure. But the reality of living there on a full-time basis is of course quite different. For John Milne the winters there were especially lonely and depressing; he might then have thought the town a cruelly indifferent sibling, to whom he was tied against his will.

Foyer: The queer lives that intersected in St. Ives between the 1950s and 70s, while under-recognized, were hardly closeted. What accounts, in your mind, for St. Ives' seeming liberalism?

Massey: Some of the former long-term residents of St Ives that I interviewed for my book stated quite firmly that Milne and his queer friends were never persecuted by the local community because of their sexuality. Yet, for all that, while St Ives in the 1950s and 1960s was in some ways a liberal place, many attitudes in the town were doubtless informed by the prevailing homophobia of the times. For instance, in my book there are details of a particularly nasty case of queer bashing that happened there in 1962, which was reported in the local newspaper. One might add, that though they formed a familiar part of the local populace, the artists themselves –regardless of their sexuality – were viewed warily by some residents, as bohemian types of questionable moral character. Such attitudes came against a backdrop of strict Methodism, in which the churchgoing fishermen and their families who formed a large part of the town’s community looked for God’s protection against the loss of life at sea. It’s also important to contextualise all of this historically; it wasn’t until 1967 that the Sexual Offences Act decriminalised consensual homosexual acts conducted in private in England. Milne and his friends knew that they were operating outside of the law, including when they were sequestered behind the high stone walls of ‘Trewyn House’.

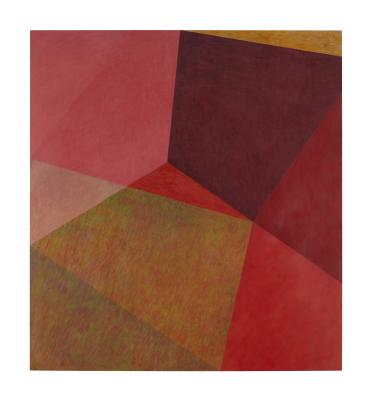

Foyer: You remind us beautifully of the important role St. Ives played in the artistic evolution of modernism. Now a popular tourist destination, and museum hotbed (Hepworth museum, Tate St. Ives) can you imagine a second act of equal import?

Massey: Artists remain drawn to the place, and there are some excellent practitioners working there now: painters, sculptors, photographers, filmmakers, ceramicists, etc. There is an artistic community in and around St Ives keen to engage with the contemporary world, and to reflect it in their work, rather than merely reiterate the stylistic tropes of 20th century modernism for which the place is so famous. But I somehow doubt that a second act of equal import could take place there. When Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, Peter Lanyon et al were active in St Ives, they had international links with the avantgarde in Europe and North America, and were part of the drive – an essentially utopian one – to form a modernist ethos that related to the social and political ideals that had become especially urgent during the post WWII period. I don’t think that there is a comparable drive now. But were one to develop, it might arise from artists concerned with environmental issues, of whom there are a number currently active in Cornwall.

Cassatt – McNicoll: Impressionists Between Worlds is on view now until September 4, 2023 in Sam and Ayala Zacks Pavillion, located on level 2 of the AGO.

Queer St. Ives and Other Stories is published by Ridinghouse UK, and a copy is available in the AGO’s E.P. Taylor Library & Archives.

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)