Exploring women's artistry with Making Her Mark

The editors of the exhibition catalogue explain why celebrating women artists is groundbreaking

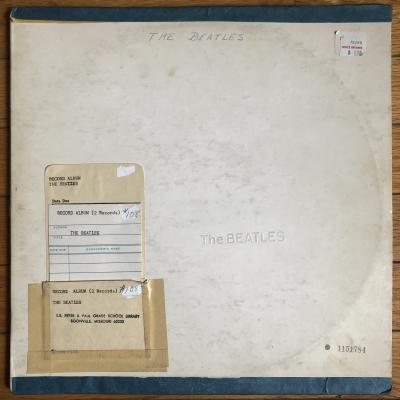

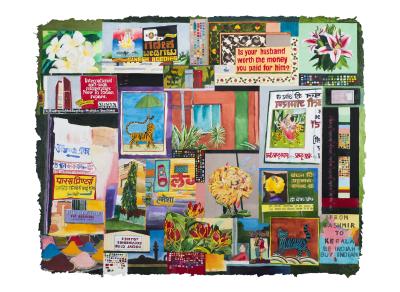

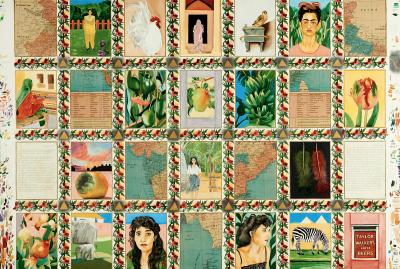

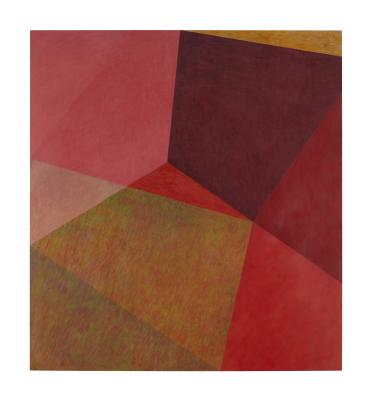

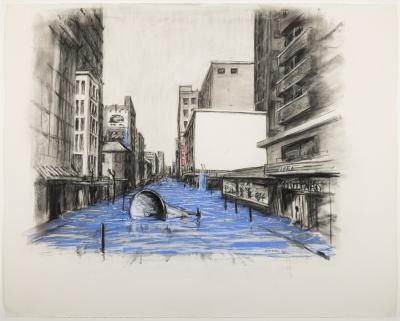

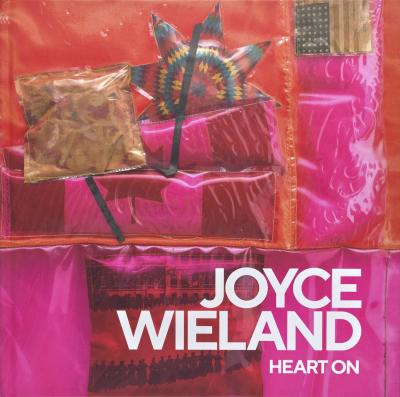

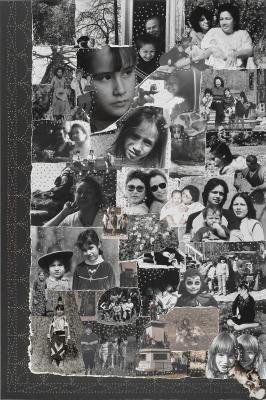

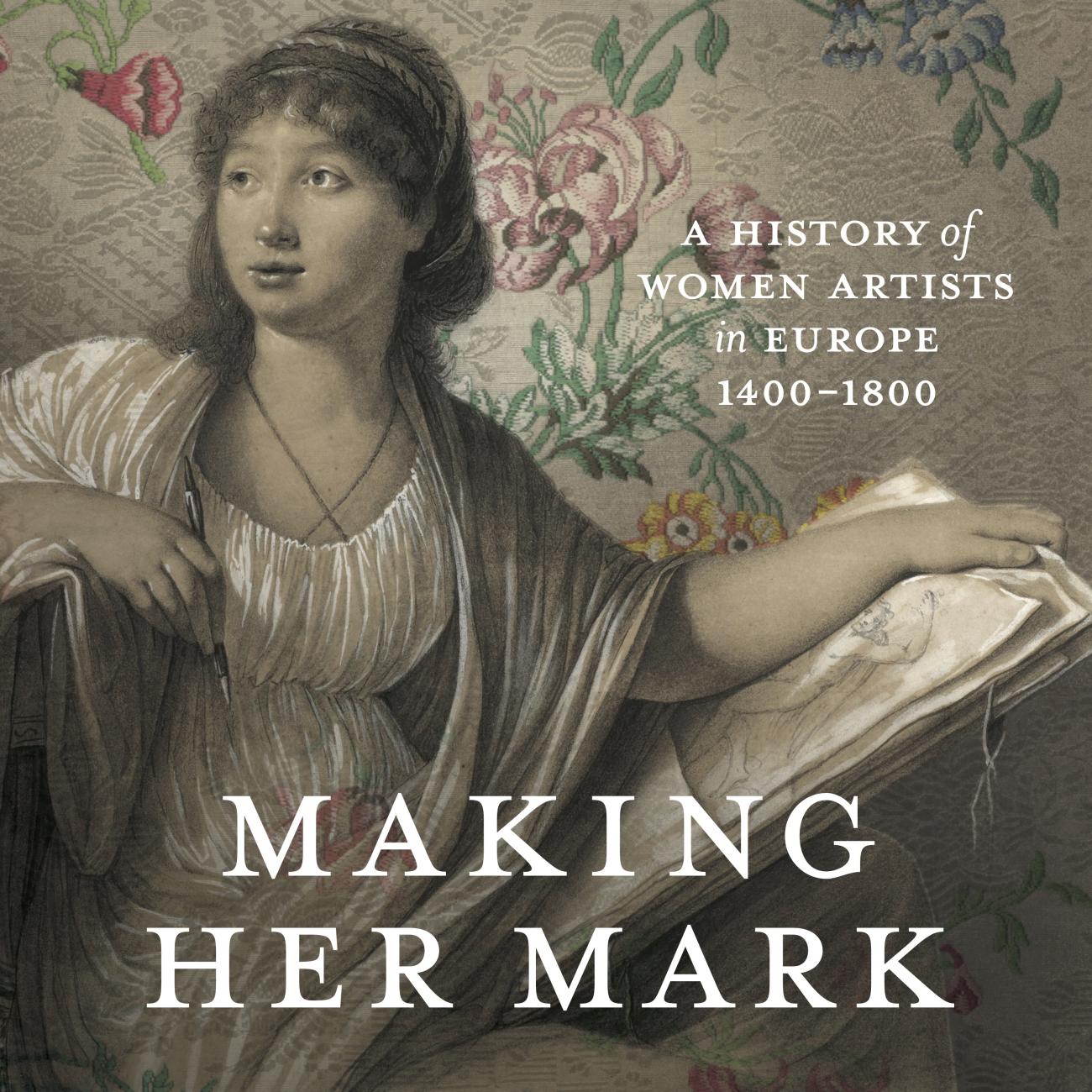

Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800, co-published in 2023 by the Art Gallery of Ontario, Baltimore Museum of Art and Goose Lane Editions. Image courtesy of Art Gallery of Ontario, design by Lara Minja of Lime Design.

This International Women’s Day, the AGO is busy preparing for a major exhibition dedicated to women artists and makers of pre-modern Europe. Demonstrating the many ways women contributed to the visual arts in Europe, the exhibition features more than 230 artworks and objects ranging from the purely decorative to the scientific. In the following excerpt from the accompanying publication, editors Andaleeb Badiee Banta, Alexa Greist and Theresa Kutasz Christensen, describe their motivations for presenting Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800, the feminist art histories it builds upon, and the collaboration that made it possible. The exhibition opens at the AGO on March 27.

---

The topic of historical women artists has garnered a fair amount of attention in museums lately, encouraging a shift in institutional policies to address the paucity of women makers in their collections. As museums try to rectify this long-standing oversight, pre-modern European women artists’ works are achieving greater status within the art market and the public imagination. Organizing an exhibition devoted to women makers during this moment has been exciting and gratifying, to be sure, but also makes clear how our collective perspective continues to be shaped by biases toward narratives of exceptional and solitary genius.

In our efforts to counter this prevailing approach, we found ourselves—as many have—returning to a foundational exhibition of women artists of the past: Anne Sutherland Harris’s and Linda Nochlin’s Women Artists, 1550–1950, first installed in 1976 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Their laudable and historic efforts resulted in increased scholarly interest in women artists and makers from the Middle Ages to the present, establishing a robust tradition in which this exhibition takes part. The curators’ broad sweep of geography and chronology inspired our scope, as did their general intention to bring greater awareness to women’s artistic accomplishments. Yet, despite the important findings this exhibition offered, its approach to understanding women’s contributions to, and status within, the artistic culture of early modern Europe still subscribed largely to the male-established criterion of singular brilliance with a paintbrush.

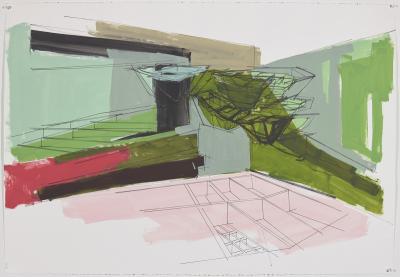

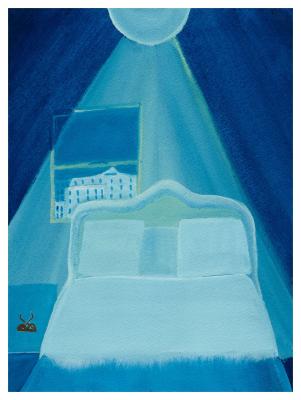

Even in the face of significant development of gender and women’s art historical studies in the nearly fifty years since then, women artists continued to be categorized as rare and comparatively less talented against this standard. Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe,1400–1800 challenges this characterization and shifts focus onto the wide variety of objects made by women. With the aim of presenting a more accurate and diverse range of women’s creative accomplishments, we established several underlying parameters. Foremost was the decision to expand upon the typical painting-centric focus and include various channels of visual creativity that reflect women’s collaborative, silent, or adjacent roles in that production. A purposefully broad geographic scope helps elucidate the variety of women’s socioeconomic situations and how they played out in differing religious and societal contexts. Diversified market forces in the Netherlands and German city-states offered different opportunities than those available to women living in essentially still feudal territories within Italy and the Iberian Peninsula.

Similarly, a wide chronological span allows for the tracking of societal changes over time, such as the lessening of social and professional restrictions imposed on women as well as the impact of major political events or intellectual developments. Traditional art historical methodologies—such as sorting out attributions or identifying makers’ relationships to prevailing stylistic movements—are less of a concern as they have long been used to exclusionary effect and discount the different priorities and circumstances that dictated creative production. We do not deny male artists’ involvement or attempt to present a fantastical world in which women makers operated independently from their circumstances, thereby risking what Griselda Pollock calls the “ghettoisation” of feminist art history. We have also endeavoured to curb the impulse to impose current feminist and gender ideologies that would have been largely incomprehensible to women of the past. Instead, we hope to focus the spotlight on the polyphonic contributions of women makers—exceptional and unexceptional alike—active during the four centuries between the origins of the Western canon and the modern era.

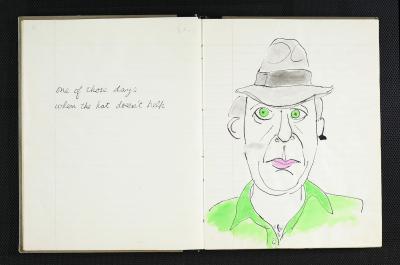

While the absence of documentary evidence for the lion’s share of creative women makes it difficult to treat each individual or society with the same degree of detail, we do hope that calling attention to the prevalence of silent labour or the many facets of artistic production will encourage consideration of unnamed women’s participation. As many have noted since Nochlin’s provocation to go in search of the “great” women artist, the true reach of women’s work has long been hidden in private collections and in museum storerooms, frequently obscured by the attribution of their work to male artists. Closely related is the inherent delicateness of the objects many women made. Women’s work for the domestic sphere—such as shell work, embroidery, paper rolling, wax, and hair work—are particularly limited by their fragility, which drastically impacts access to extant examples in good repair. While literature produced by women resides tucked away in archives and libraries, the material goods made by even the most accomplished women makers were often utilitarian, meaning that they frequently deteriorated due to daily use or fell out of fashion over time. Some of these works have suffered from later appraisals by scholars and curators who determined that objects based on mass-produced patterns or kits were not the result of an authentic creative process. In addition to containing light-sensitive materials, like textiles or paper, these works are often intermedial, existing between museum-collecting departments and therefore less likely to receive sustained attention from curators. Certain media are so fragile and difficult to lend that a number of important works—including those by Anna Morandi Manzolini (1714–1774), Caterina de Julianis (1670–1743), Mary Delaney (1700–1788), and the enclosed garden altarpieces of the women of the Flemish Beguine convents—cannot be properly represented here. By no means does this exhibition or catalogue offer an exhaustive representation of women makers in Europe in the centuries selected.

Even as we committed to the final checklist, new works surfaced. Readers may note greater representation of work from later centuries; this is not intended to favour those periods or imply that women across Europe necessarily played greater roles overall in the production of art in those periods. Instead, this imbalance is a reflection of better archival support for the documented professionalization of women in the arts as well as greater numbers of extant examples stable enough to travel or be put on display. Although there are episodes of global reach woven throughout, the focus remains on Western Europe in a conscious effort to subvert the dominant narrative of male-centred standards for the Western canon and to prevent an unwieldy checklist. This restriction, however, hampered our ability to thoroughly engage with the question of women makers of non-European origin, or the exchange between European women artists and those trained in non-Western traditions. Further, the topic of artistic output by historical gender non-conforming individuals was not something we could address properly with the works we were able to include. We do not intend to negate their existence or erase their contributions, as surely they were part of these artistic communities. Rather, the state of scholarship has not yet led us to specific artistic examples that could concretely illuminate their identities. Equally frustrating was the inability to include objects representing named women makers of colour. While women of colour doubtlessly engaged in the broader production of works of art during this period, thus far it appears to have remained in the same silent or undocumented capacity that applies to the majority of women during this period. We hope to be proven wrong in these last statements, and that future discoveries will lead to many more inclusive and expanded explorations into women makers of the past.

Major essays in this catalogue address a broad range of media, with the goal of offering a variety of perspectives on women’s far-ranging and ubiquitous involvement with all manner of artistic materials and sites of creative production during the centuries covered in this exhibition. Following these broader investigations are concise object-focused essays, organized by media, that take the place of traditional catalogue entries for the works presented in the exhibition. This format is intended to undermine the traditional monographic approach, one that has long favoured male artists. Further, abandoning the focus on individual identities allows for an integrated discussion of the objects with unknown makers, and builds a picture of how women worked in medium-specific contexts. To find a work from the exhibition, consult the medium-specific chapters starting on page 159; to find an artist, consult the index of women makers with works illustrated in the catalogue, located at the end of the volume. As with any major project, this undertaking was the result of a collaborative effort. The team dynamic that under girded its research, organization, and execution felt wholly appropriate to a project that aims to decentre the traditional concept of the individual male artist working in isolation. We are grateful to the dozens of colleagues, scholars, and friends who have contributed generously and with great enthusiasm.

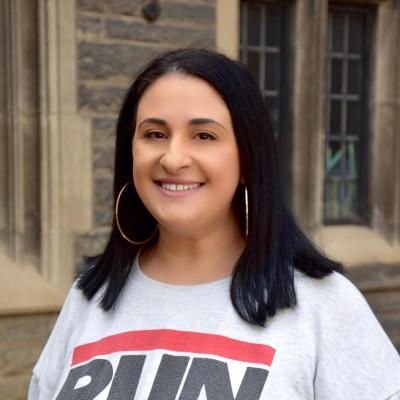

Text by Andaleeb Badiee Banta Senior Curator and Department Head, Prints, Drawings & Photographs, Baltimore Museum of Art, Alexa Greist Curator and R. Fraser Elliott Chair, Prints & Drawings, Art Gallery of Ontario, Theresa Kutasz Christensen, Exhibition Research Assistant, Prints, Drawings & Photographs, Baltimore Museum of Art.

Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800 opens on March 27, 2024 at the AGO. It is accompanied by a 264 page, fully illustrated hardcover catalogue, co-published by the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Baltimore Museum of Art, and Goose Lane Editions. Edited by Andaleeb Badiee Banta and Alexa Greist, with Theresa Kutasz Christenen, it features essays by Babette Bohn, Madeleine C. Vilijoen, Yassan Croizat-Glazer, Britany Luberda, Virginia Treanor and Paris A. Spies-Gans. The catalogue is available now at shopAGO.