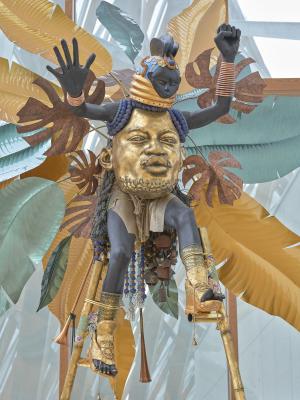

Magdalene Odundo’s earthly vessels

Odundo’s sculptures examine the relationship between clay, nature, and humanity

Photograph courtesy of Cristian Barnett Photography

Sensuous curves in orange and black — the vessels of Dame Magdalene Odundo signal an intrinsic relationship between clay, nature, and humanity.

On view at the Gardiner Museum until April 21, Magdalene Odundo: A Dialogue with Objects marks the artist’s Canadian debut and the largest exhibition of her work in North America. Featuring over 20 works spanning Odundo’s career, her vessels are presented in dialogue with contextual objects from other museums in Toronto, including the collections of the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) and the AGO.

First pursuing graphic design in her home country of Kenya, Odundo moved to the United Kingdom in 1971 to study at the Cambridge School of Art. There, she began to work with clay, changing her career trajectory. Since the early 1980s, Odundo has focused her practice on creating refined, magisterial ceramic vessels, her style becoming unmistakable.

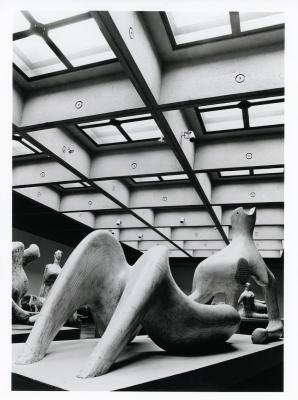

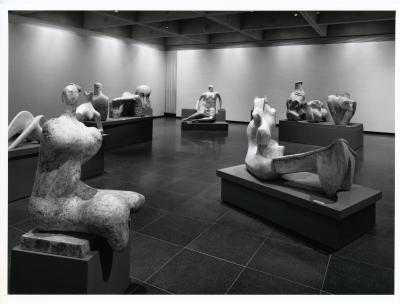

Photo taken by Toni Hafkenscheid

The characteristic colours of Odundo’s vessels are the natural result of oxidation and reduction reactions between oxygen, heat, smoke and clay. Smooth and lustrous, her vessels have familiar features: rounded bellies, elongated necks, and small protrusions. With an intrinsic connection between clay and humanity, Odundo’s vessels unmistakably reference the human body.

“Clay is a fundamental material that has nurtured and sustained life on earth for all time,” she explained. “I cannot think of any living creature that does not rely on earth (clay) in some way. It is an extension of our human existence and historically the first material to be used to mould and shape objects for function and spiritual purposes.”

Magdalene Odundo, Vessel Series II, no. I, 2005-6. Ceramic, H 56.5 × 28.9 cm (H 22 1/4 × 11 3/8 in.) Maxine and Stuart Frankel Foundation for Art. Photo: PD Rearick

This connection between clay and spirituality is explored throughout the exhibition, mainly through what is not visible to viewers: the inner space of Odundo’s vessels. Furthering the connection between the human body and vessels, Odundo sees the inside of her vessels as a sacred, protected space, just like our own inner worlds.

The exhibition also emphasizes the political aspects of Odundo’s work by exploring how her vessels represent the artist’s response to the effects of colonialism. Much of Odundo’s early life and career was marked by political and social change, including African independence movements throughout the 1960s-70s and the emergence of the Black Panther Party during her early years in Britain.

“When you are present while these events are unfolding, they are lived experiences, and they affect how you perceive yourself and how you live your life,” she said. “These events have truly impacted the way that I live, think, and the work I make.”

Magdalene Odundo, Untitled, 1995. Ceramic, 50.8 × 29.2 cm (H 20 × 11 1/2 in.) Maxine and Stuart Frankel Foundation for Art. Photo: PD Rearick

The political dimension of Odundo’s work may not reveal itself at first glance. Compared to other artists examining colonialism and the African diaspora, Odundo takes a more subtle route. Her minimalist vessels lead the viewer towards introspection. For Odundo, the interiors of her vessels represent an inner silence that allows her to reflect on and navigate the effects of colonialism.

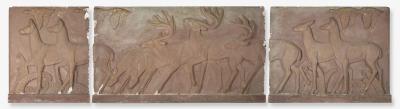

Odundo’s vessels are made entirely by hand, using small tools instead of a pottery wheel. In 1974, Odundo completed an apprenticeship in Nigeria at the Abuja Pottery Training Centre, working under accomplished Gbayi potter Ladi Kwali. The influence of her training in traditional West African pottery still evident in her work.

Photo taken by Toni Hafkenscheid

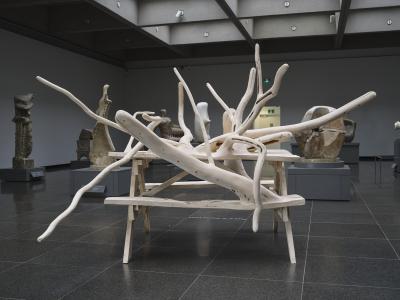

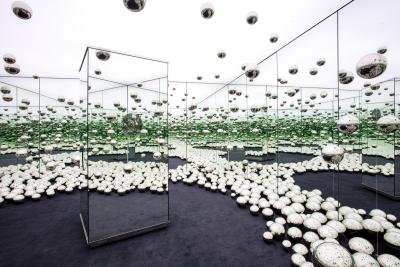

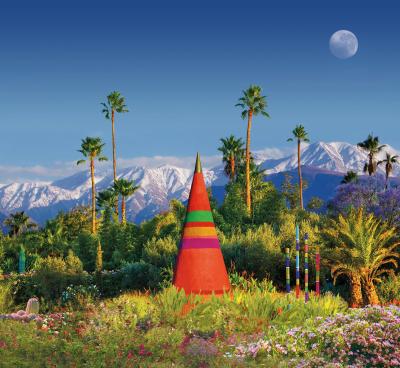

Highlighting how Odundo pulls from both African and global traditions, the exhibition places contextual objects from diverse backgrounds in dialogue with Odundo’s vessels, including carved stone works found in archaeological settings across present-day Ontario and the Great Lakes, a ceremonial tunic from Indonesia, a painting by the late Trinidadian Canadian painter Denyse Thomasos, and many more. Odundo co-curated the show with Dr. Sequoia Miller, Chief Curator & Deputy Director of the Gardiner Museum. After working with Miller to go through long lists of works from Toronto museums, the sorting criteria for Odundo became finding works that shared the same values as her pottery.

“It is so difficult to explain how a piece of work moves you,” she said. “However, I felt that [the chosen] pieces spoke to the quest for simplicity that I seek in my work.”

Photo taken by Toni Hafkenscheid

While Odundo chose many contextual works in appreciation of their utilitarian purposes, Odundo’s works themselves are created as sculpture. Returning to her perception of the interior as a sacred space for introspection and reflection, departing from the utilitarian nature of traditional pottery is a way for her to shift perspective.

“I see myself as an artist, and like other artists, I have my own narrative that speaks of an inherited history past and present,” she explained. “The history of colonialism which I grew up with influenced how I perceived the events of emancipation and the world movements for independence and the abolition of slavery. Thus, contemporary interpretations that are embedded in my work present some narrative about myself and my people.”

Experience Odundo’s vessels at Magdalene Odundo: A Dialogue with Objects on view at the Gardiner Museum until April 21.

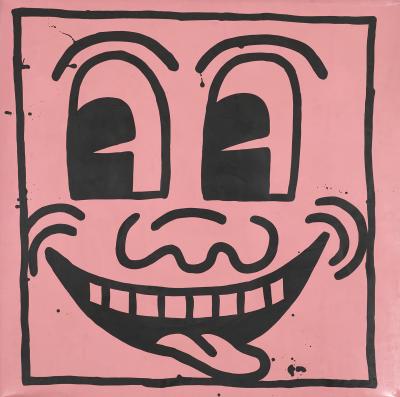

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)