Freedom and folklore

Take a closer look at Zak Ové’s Moko Jumbie, on view now at the AGO.

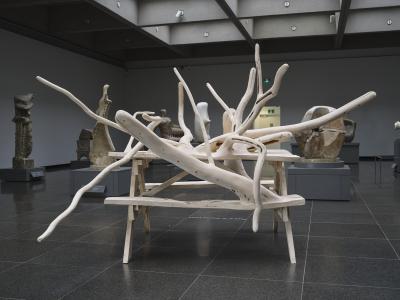

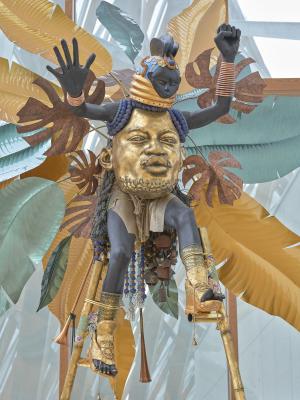

Zak Ové. Moko Jumbie, 2021. Mixed media, Overall: 560 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Commission, with funds from David W. Binet and Ray & Georgina Williams, 2021. © Zak Ové. 2021/70.

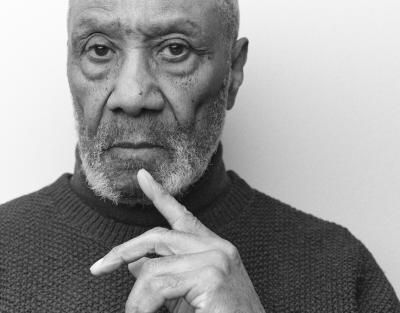

British-Trinidadian sculptural artist Zak Ové takes his artistic cues from the traditions of his ancestors. While documenting the Trinidad and Tobago Carnival as a young filmmaker in the 1990s, he became enthralled by the festival’s emancipatory pageantry, and began creating art inspired by it. The latest edition to Ové’s well-known Moko Jumbie sculptural series is on view in the AGO’s Galleria Italia, previously part of the groundbreaking exhibition, Fragments of Epic Memory [closed February 2022].

For over a century, the grand Afro-Caribbean tradition of Moko Jumbie has been a beloved fixture of Trinidad and Tobago’s annual Carnival. The pre-colonial roots of these towering deities reach back to central and West African folklore, in which Mokos (loosely translated as Gods or diviners) would watch over a village, using their elevated stature to foresee evil on the horizon. Adopted as a staple of Trinidad Carnival in the early 1900s, Moko Jumbie masqueraders stand atop 10-foot-tall stilts, adorned in elaborate costumes, marching and dancing throughout the festival. Like many other elements of Carnival culture, Moko Jumbie connects Afro-Caribbean communities to their ancestral legacy to celebrate emancipation from colonial rule.

In his practice, Zak Ové attempts to put a contemporary spin on ancient cultural mythologies. He does so by utilizing what he describes as “new world materials” and symbols in the construction of his works – picture a massive Moko Jumbie deity in a pair of shiny gold Air Jordan 6 basketball sneakers. Though the folklore of Moko Jumbie dates back centuries, the social and political context of Masquerade tradition remain equally as relevant now as it was in its inception. Describing how the ethos of Carnival inspires his practice, Ové states, “Within Masquerade there was also a championing of emancipation by use of costume; a sense of transfigurement; a sense of being able to exalt; a sense of being able to break ground from how one was duped in a colonial society.”

Zak Ové. Moko Jumbie, 2021. Mixed media, Overall: 560 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Commission, with funds from David W. Binet and Ray & Georgina Williams, 2021. © Zak Ové. 2021/70.

Ové’s Moko Jumbie sculpture is a striking, 10-foot-tall mystical figure who commands attention. Mounted atop towering bamboo stilts, its intricate details and materiality are awe-inspiring. The figure stands mid-stride in a symbolic formation – one hand clenched in an iconic Black power fist, the other outstretched with an exposed palm (possibly referencing the well-known BLM chant/ hand gesture “Hands up, don’t shoot”). It is adorned with jewellery and accessories referencing tribal aesthetics from various African regions, including bracelets of the Venda Peoples of South Africa and neck rings worn by the Ndebele Tribe, also of South Africa. Finally, it is surrounded by a grand plume of teal and gold banana leaves, resembling an angelic wingspan.

FRAGMENTS OF EPIC MEMORY SUPPORTERS

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)