Alex Colville’s Compelling Modernism

Curator and writer Ray Cronin on how Colville made the ordinary profound

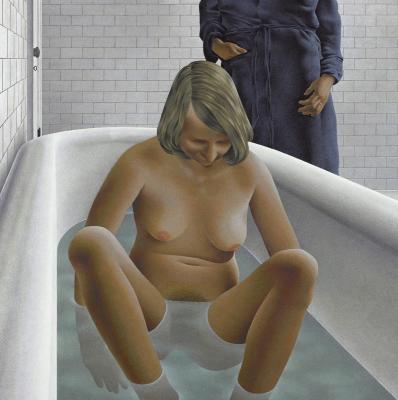

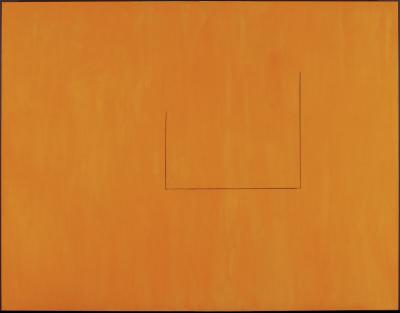

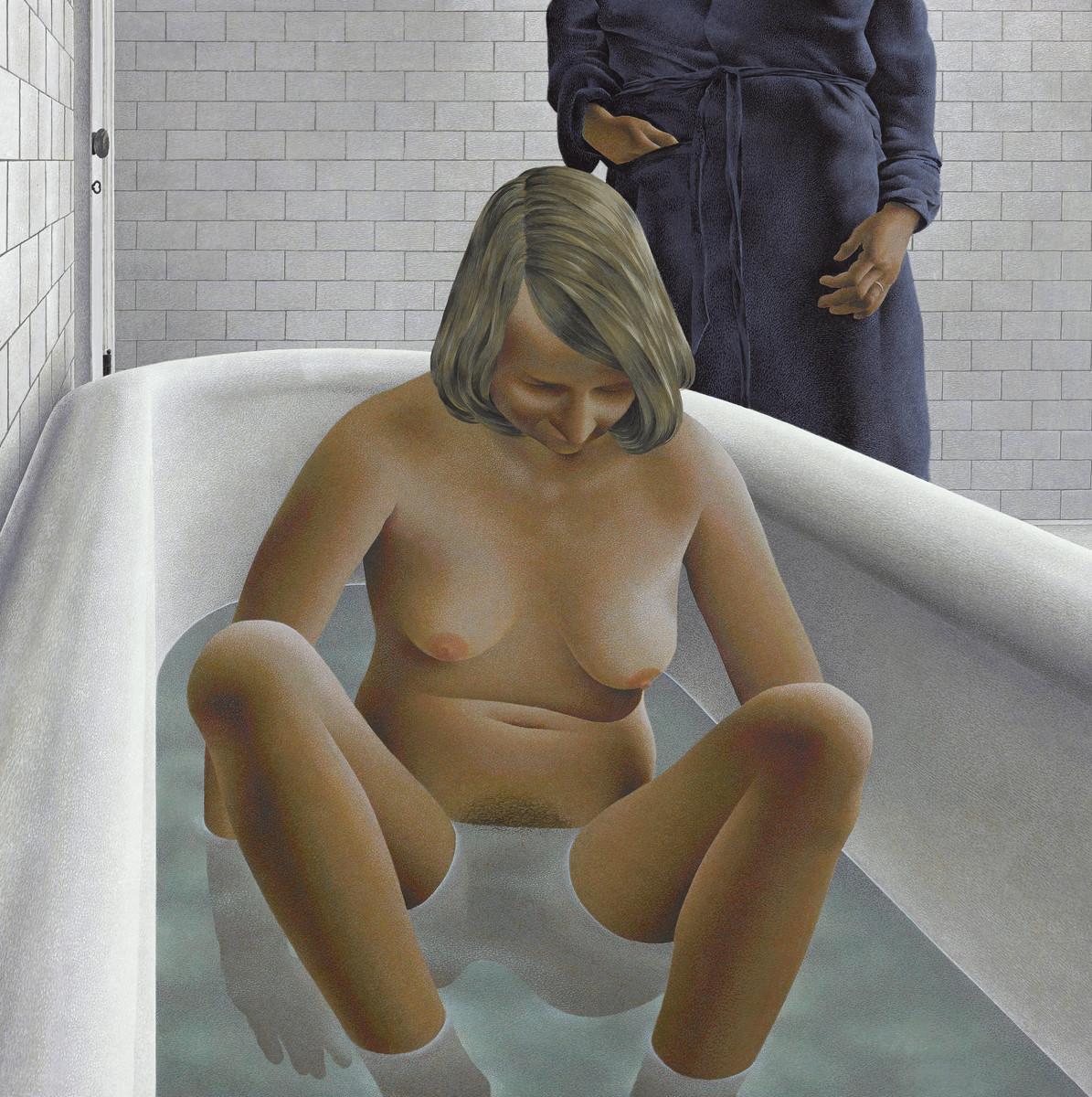

Alex Colville. Woman in Bathtub, 1973. Acrylic polymer emulsion, Overall: 87.8 x 87.6 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Purchase with assistance from Wintario, 1978. © A.C. Fine Art Inc. Photo: AGO. 78/124

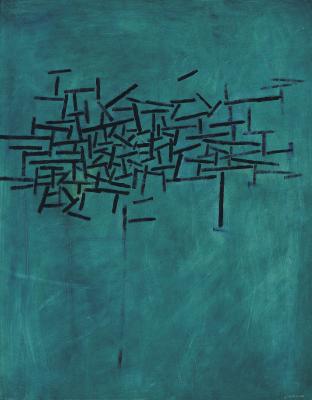

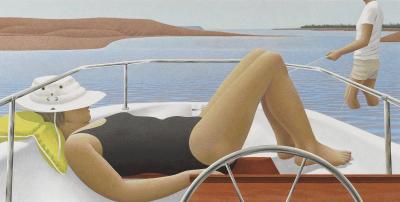

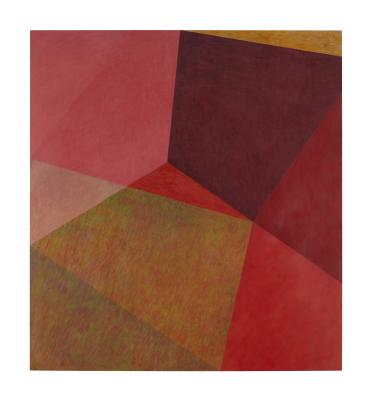

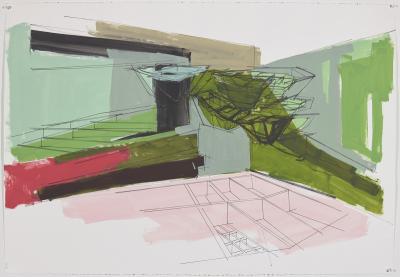

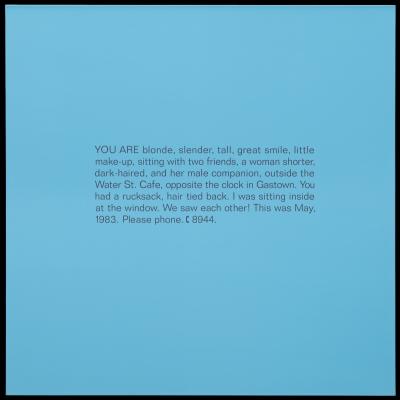

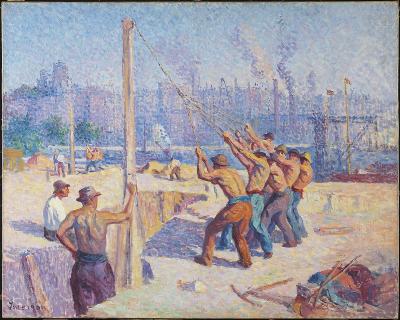

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, from Toronto to São Paulo, painters began rejecting figuration and perspective, embracing colour, scale and line, in pursuit of a more expressive and immediate experience. Exploring this impulse is the current exhibition Moments in Modernism, a unique conversation between artists of the era. Nestled amongst the many large-scale abstract works on view, some of the most popular are those by Canadian painter Alex Colville (1920 – 2013), an artist whose highly controlled, but not quite real portraits of family and the Maritimes, have earned him fans around the world. Exploring Colville’s particular expression of place and his relationship to Modernism, the AGO welcomes Ray Cronin, Curator of Canadian Art at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery on April 9 for a public talk.

Before his talk, Foyer reached out to Cronin to chat about why Colville continues to compel us and what makes him so modern.

This conversation has been edited and condensed.

Foyer: You've written a lot on Colville. What keeps you coming back to his work

Cronin: In part, it is because his work is so central to late modernity and is an existential response to World War II. He was someone who thought very long and hard about what it meant that the first half of the 20th century was chaos. His response to the bloodshed, the incredible tragedy of it all, was very thoughtful, very philosophical, and asked what it meant to be human in the world. It's not unique – those questions permeated philosophy and art and culture in the 50s and 60s into the 70s. My father was a philosophy professor, and I always responded to Colville’s brand of thoughtfulness. Coming of age as a curator at a time when we struggled (and still do?) to understand what the post-modern is and worked against what came before, his works stuck out for me as something compelling, that can’t be dismissed.

Did you ever meet Colville?

I had the pleasure when I worked at the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia, to meet him several times. I got to visit him in his house, even had a couple conversations about philosophy. He loved that I had continued to read philosophy recreationally. A good friend of his, at Mount Allison, was a friend and colleague of my father's. And he liked that connection.

Ray Cronin, Curator of Canadian Art at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery. Photo by Steve Farmer.

There is an enduring perception of him as being a very isolated, withdrawn individual. Did he see himself that way?

He said himself that he went to Sackville to be isolated from the art world. But what he wanted was to avoid its influence. He wanted to be in a place where he could just concentrate on his own vision. That wasn't very flattering to his colleagues at Mount Allison but was how he felt. After serving in the war, being a war artist, and having had an art studio in London, he consciously turns inward.

But importantly, his work is still showing in New York, he was showing in Berlin, he was showing in London. He just wasn’t there. He deliberately sought out a place where he could really drill down to his own vision, his own sense of what he wanted to express. And for him, Sackville, and then later, Wolfville did that. His is probably the most biographical work by any major Canadian figure that I can think of, in terms of his subject. His children are depicted from their youth through to adulthood, particularly his daughter. And you see 60 plus years of marriage, through portraits of his wife Rhoda, in addition to self-portraits from his youth to his late 80s. His work is a remarkable human document.

Moments of Modernism highlights how central New York was to abstract expressionism. What was Colville’s relationship to the conversation happening there?

Colville comes to New York in the 1950s at the time when the art world was at an inflection point, poised to follow one of two strains – abstraction or a more figurative approach likened to magical realism. His work can be considered part of the latter, this alternate vision of modernism. But the dominant taste quickly moves to abstraction– which was completely antithetical to his way of thinking about making a painting. And Colville was just not an abstract artist. He liked good painting, whatever it was. But he didn't think that way.

His purposeful move away from the New York scene also reflects his pace. He couldn't make enough paintings in a year to satisfy a Soho commercial dealer, and he didn't want to work on that kind of treadmill. Two paintings and a serigraph were a very productive year for Colville. And there was always a lineup of people to buy those, so he didn't need to push. He wasn't somebody who rejected the art world. He just didn't work in their way.

Yet he becomes huge in Germany. How?

I think it had to do with the fact that they are very thoughtful, very existential paintings. They're very much about coming to terms with a world in which all certainties have been erased. I find parallels between Colville and the French philosopher Albert Camus’s idea of the conservative rebel, and the need to build in the face of chaos. Which is what Germany’s response to the Second World War was, they insist on order and do the work to build it, to recreate the sense of themselves. I think Colville’s work dovetails nicely with someone like Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer and their look at German history and psychology. And I can see why his work was so popular there.

Moments in Modernism brings their work (Colville and Richter) together. Do we know if Colville had a relationship with Richter?

There was a person who connected them – Colville knew Garry Neil Kennedy quite well, and Kennedy (then President of NSCAD) and Richter were quite close. Richter had his very first North American exhibition in Halifax, but whether Colville saw it, I don’t know. Richter showed a series of abstract paintings there that were for sale for like, under $500 and not a single person bought one.

There's an apocryphal quote, that one always knew when Colville was starting a new painting, because he would be out measuring the dog. Tell me about his interest in geometry.

That’s a true quote. Geometry for Colville, it goes back to order. It goes back to the sense of balance. He's very interested in the unity of a picture. He made these images that have the appearance of a chance observation, right, a random moment? But when you break them down or analyze them, you realize that these paintings have repeated forms, that there's relationships between the forms, and that it’s his various interlocking rectangles or circles that tie the image together. His paintings never spill off the edge, but rather spiral into the centre and have a very logical completeness to them, which is the result of geometry.

He's thought of as a realist, but if what he was depicting didn't fit the geometry, he had no problem with changing it. Certainly, he used sketches, he used photographs, he used actual objects as his source material, but he would put compositions together that reflect an idea about reality, rather than what was real. He was composing an image from elements drawn from the world but then marshaled or organized it visually through this detailed mathematical process.

What he found through these processes was a way of helping to amplify the universal quality of his work. Very aware of the ability of Medieval and Renaissance religious paintings to speak to everyone, and the post-war era’s lack of unifying imagery, it was in pursuit of something solid, that he looked to geometry to make the ephemeral seem eternal.

Of the Colville paintings on view in Moments in Modernism, is there a standout in your mind?

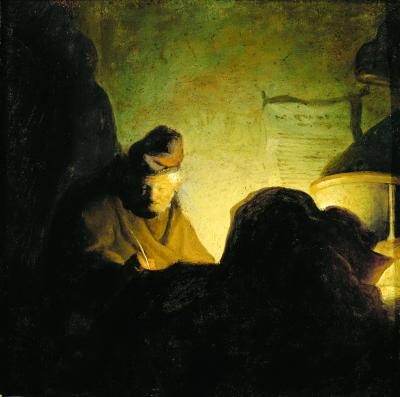

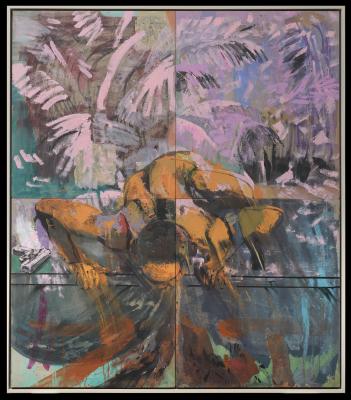

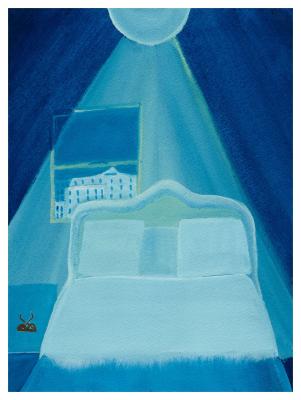

Woman in Bathtub (1973) is, I think, an absolute perfect Colville painting, in many ways. It's about this incredible intimacy of a married couple, which is a constant theme in his work. It's not the kind of thing you see in art very often. It's not a heroic painting but does have this kind of brooding quality. People often feel a kind of menacing quality in Colville's work, but I think the painting is more an expression of the role of family. He often would say, the world is menacing, but the family unit is what protects us.

Here at the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, we have a remarkable Lucien Freud painting called Hotel Bedroom (1954), featuring a wife in bed, with her husband brooding in the background. Someday, I'd like to see it hung beside Woman in Bathtub. They share a similar awkwardness and existential kind of angst, but at the same time, the woman in both is not someone who's looking threatened or cowed. Anyone who's lived with a domestic partner has experienced seeing the other while they're having a bath or shower, right? It's a very common thing that Colville makes us feel is brooding, deep, strange and compelling. His genius was his way of making the ordinary so profound.

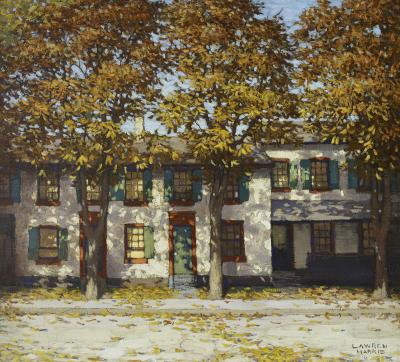

Alex Colville. Circus Woman, 1959-1960. Oil and synthetic resin, 66 x 76 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of Dr. Helen J. Dow, 1991. © A.C. Fine Art Inc. Photo: AGO. 91/85

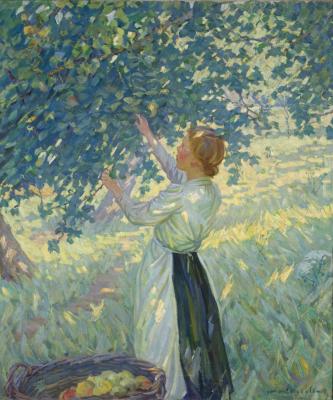

Amongst the paintings on view, am I right in thinking Circus Woman (1959-1960) stands out somehow? It’s not an obvious maritime or family setting.

That's a weird one, right? One of the artists Colville loved was the Italian Renaissance painter Andrea Mantegna, who has a painting of a foreshortened Christ figure that is seen from the feet, and I think that composition is replicated somewhat here. Colville was very adamant that, after the war, when he was living and painting in London, he was spending his time at the National Gallery seeing Renaissance paintings. He didn't pay much attention to the contemporary art around him, except for Henry Moore, who was a huge influence.

What aspect of Moore’s work inspired Colville?

Moore’s underground shelter drawings for sure. He was impressed by them. In Colville’s early work, from 1952 to the late 50s, his figures are very sculptural. People often attribute that as an expression of magical realism, or surrealism, but I see it as being more about the figure. If you look at Colville’s early figures, they are very statuesque, very Henry Moore. It doesn’t last, of course, and Colville’s figures become less symbolic, or less idealized, through the rest of his career. But Colville's first images are very suggestive of statues in an empty room rather than people who are alive in a house.

See the artistry of Alex Colville, on view now as part of Moments in Modernism, on Level 4 of the AGO.

Moments in Modernism was co-curated by Debbie Johnsen, Assistant Curator, Contemporary Art, and Stephan Jost, Michael and Sonja Koerner Director, and CEO. Moments in Modernism features artworks that will form the cornerstone for the expansion of the new Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery, starting construction in 2024. The new building is being designed by architects Diamond Schmitt, Selldorf Architects and Two Row Architect to showcase the AGO's growing collection of modern and contemporary art.

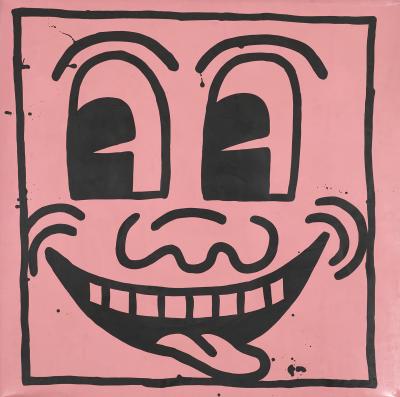

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)