In conversation with Sarindar Dhaliwal

The South Asian Canadian artist reflects on childhood memories and 40 years of artmaking.

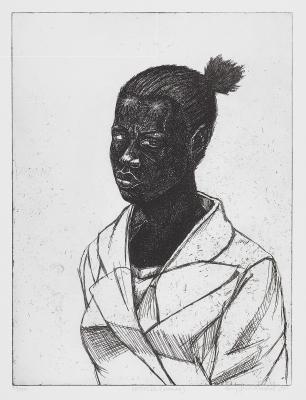

Sarindar Dhaliwal with her work, Hey Hey Paula, 1998. Installation consisting of 544 inkjet photographs on Fujiflex polyester paper, muslin curtain, rotary telephone with audio on a painted wooden table. Dimensions variable. © Sarindar Dhaliwal. Photo: Craig Boyko © AGO

For Sarindar Dhaliwal, the transition from a seed idea to completed artwork often takes several years of fervent study, intuitive travel and deep reflection. The powerful colours and captivating imagery in Dhaliwal’s work invite viewers to look deeper and discover a rigorous investigation of memory, migration and identity.

On view now at the AGO, Sarindar Dhaliwal: When I grow up I want to be a namer of paint colours exhibits more than 40 years of artwork by the artist. The exhibition marks Dhaliwal’s first at the AGO and consists of significant works from her oeuvre, including drawings and mixed media works from the 1980s to the 2000s, alongside large-scale installations and recent photography. Curated by Renée van der Avoird, Associate Curator, Canadian Art, the show highlights four recent AGO acquisitions, among them: Hey Hey Paula (1998) and the cartographer’s mistake: the Radcliffe Line (2012).

Dhaliwal was born in Punjab, India and moved with her family to England at the age of four, where she grew up in Southall, London. At fifteen, she migrated again with her family to Canada. She received a BA in Fine Art at Falmouth University, Cornwall in England (1978), then moved back to Canada, where she currently lives. She gained a MFA from York University in 2003 and a Ph.D. in Cultural Studies from Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario in 2019.

A week before the exhibition’s opening, we met with Dhaliwal for a conversation. In the midst of installation – with rolled up sleeves, writing crimson text directly on the wall – she graciously took a break to chat about childhood memories, pivotal moments in history, and the epic backstories attached to key works from the exhibition.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

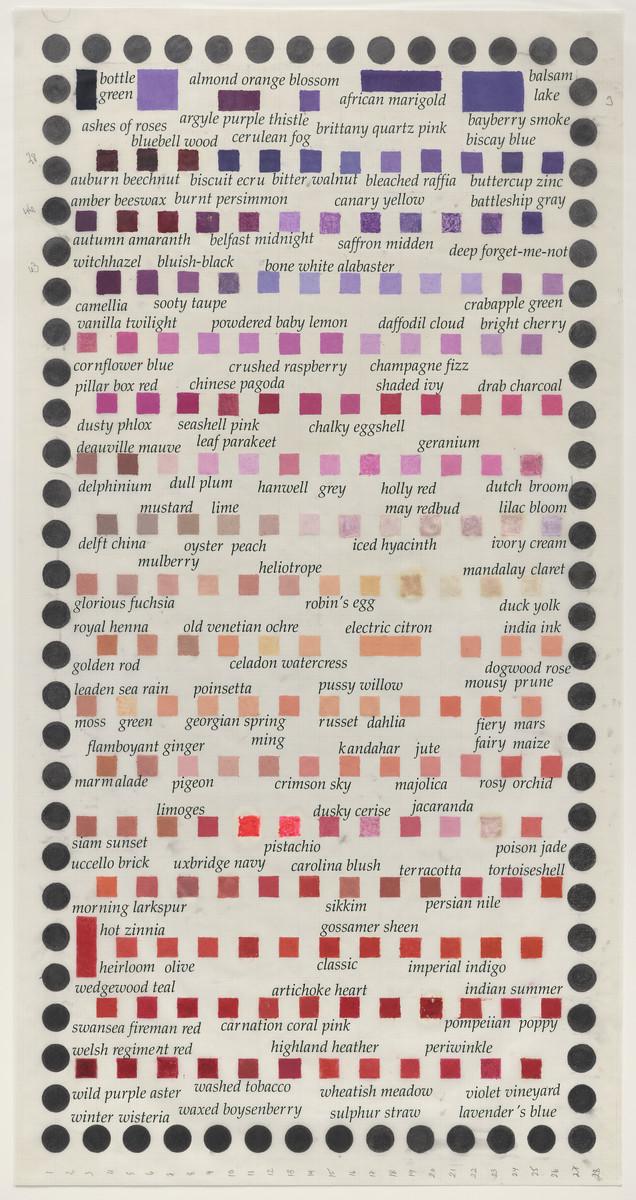

Foyer: The title of your work, When I grow up I want to be a namer of paint colours doubles as the exhibition's title. Can you share with us the origin story of that specific work, and why you feel its title also serves as a representation of your work in general?

Dhaliwal: Sometimes, I think of the title before I make the piece. You know when you go into a paint shop, and there are paint chips, and they have the titles of the colours? I always thought that would be a great job to have. One of the things I've noticed in Canada is that when they name streets, sometimes they can be quite boring. There’s a street near where I live called Canmotor – who in the world would call a street that? I find the names of the colours of paint chips far more poetic.

I went to France – I was probably there for five weeks, in Brittany. I knew I was going to make something there, but I don't think I knew what it was, so I took some mylar [painting or drawing surface]. Since I was travelling, I didn't want to take all the pastels that I have, so I picked a range that was between various reds and pinks and purples. When I arrived, I started to make these colour swatches, but I still didn't know what the piece was going to be. When I came back to Canada, I decided that I wanted to use Letraset [dry transfer lettering] to make names of colours. Deauville Mauve is one. Belfast Midnight, another. When I was putting the Letraset on, I was very conscious of the letters themselves. Sometimes there'd be a colour that had two Z’s, then beneath it,, I'd find another colour that had two Z’s or two R's. So it was done very intuitively, without any real conceptual meaning.

Sometimes when the work was interpreted, people would think, “Why is she calling a swatch that's pink, Belfast Midnight?”, They felt like I was actually saying something with that – but I wasn't. I was just working visually and enjoying making things. Renée [van der Avoird] and I tossed around a few ideas for the title of the show, and that one seemed most poignant because almost every piece in the show has something to do with colour to some degree.

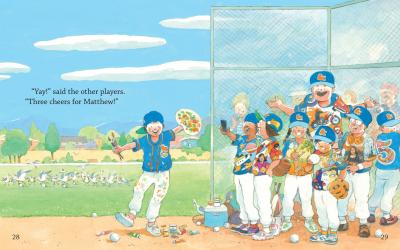

Sarindar Dhaliwal, When I grow up I want to be a namer of paint colours, 2010. Mixed media on mylar, 152.4 × 86.4 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Sarindar Dhaliwal. Photo AGO.

Foyer: Your work incorporates such a vast array of materials and mediums. When you conceive of an idea for a new artwork, how would you describe your process for narrowing down the technical approach and deciding what materials and mediums to utilize?

Dhaliwal: When I make a work, at first, it is just an idea – it’s usually not fleshed out. Then it's the coming together of materials to make the work. Sometimes, however, I begin by seeing the work as finished in my head. There is a work in the exhibition called The green fairy storybook. Its various elements came together over several years.

Since the 80s, a lot of my work has been about looking at my childhood, and the dissonance of being an immigrant child. It's much different now, but in the 50s and 60s, you were pointed out, and you were seen as something that polluted the nature of how the host country wanted kids to be. My mother was illiterate, but I loved reading. So I would go to the public library to read a series of anthologies by an author named Andrew Lang. They were all colour-coded fairy storybooks – there was the green fairy book, the yellow, the lavender etc. I would bring these books home and spend time reading, but my mother saw reading as a very lazy activity. She would say, “If you don't stop reading, you're going to fail at school.”

Many years later, I went to a place called Pondicherry in India. It has a history of being a big ashram city. They used to have a papermaking facility there. I found a large room stacked with sheets of paper of all different colours. So I bought paper from them and they shipped it here to Toronto. Once I had the paper, I went to a bookbinder and asked them to make me books of various colours. Then I had to write the text, which went on the spines of the books, to be read horizontally. It tells the story of learning to read and my love of books.

Lastly, I needed to decide how this work would be displayed. I had met a man who worked for the film industry in Montreal, and he was an exceptional carpenter. I asked him if he would make a special table for the books, and he did such a great job that it actually looked like a table from the 1950s. None of these elements come to me at the very beginning, they gradually morph into a work.

I think the work is very unusual in that way because it has these very personal anecdotes, but it's almost a way of fixing the past. I've always seen it as psychological. It's like, once I make the work, then I can forget about my mother not understanding how important reading is.

{"preview_thumbnail":"/sites/default/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/4L6sy0eEhZw.jpg?itok=SlocKNIJ","video_url":"https://youtu.be/4L6sy0eEhZw","settings":{"responsive":1,"width":"854","height":"480","autoplay":0,"title_format":"@provider | @title","title_fallback":true},"settings_summary":["Embedded Video (Responsive)."]}

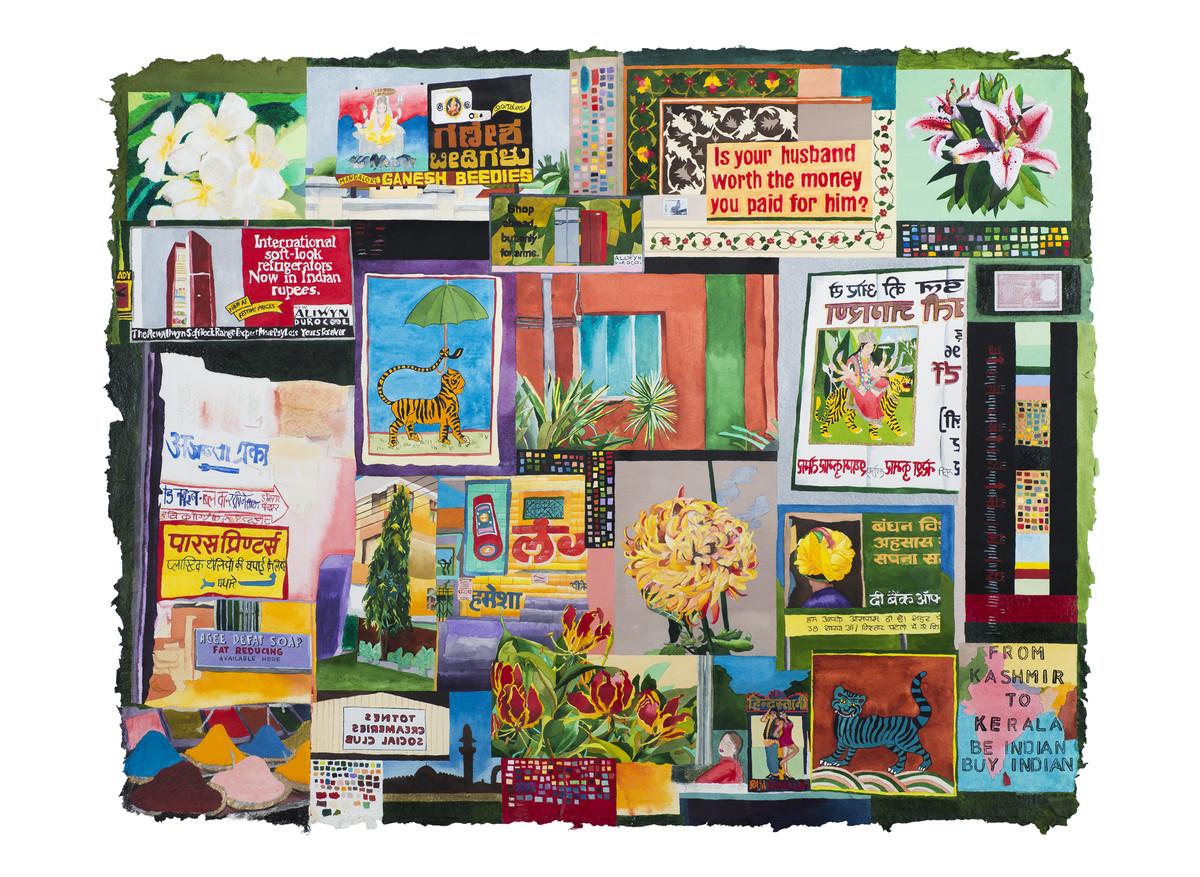

Foyer: In much of your work, there’s a recurring technique of tiled segmentation. Among other works, it is present in Hey Hey Paula, Oscar and the Two Fridas and Indian Billboard. What has drawn you to this technique? Why is it such a staple in your practice?

Dhaliwal: When I started to paint during the first year of my BFA, I made a still life of a savoy cabbage and other vegetables. My professors at the time didn’t approve of the techniques I was using, and I eventually decided to major in sculpture instead. Years later, I began to paint again in Kingston during my Ph.D. I wanted to paint on large sheets of paper but wasn’t able to, because I hadn’t learned how to paint on that scale. It was easier for me to find all the different kinds of images and make them small. It's a bit like a bunch of miniatures, pieced together to make a bigger picture.

I think it's often just images I like. Almost all of them are images I've taken as a photographer. I think that gridded way of working means I can make large works without having to worry about people seeing it as a whole – even though I think it works as a whole. Often, I could start work, and I might not know what all of those squares are going to be. Then I may finish one and think of other images I have that could work in the remaining squares.

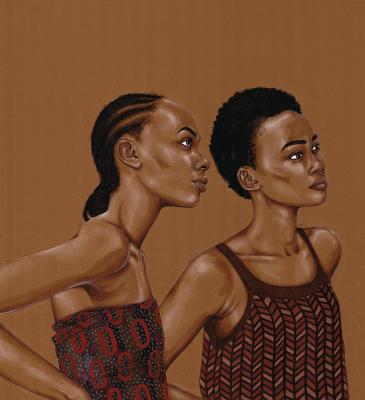

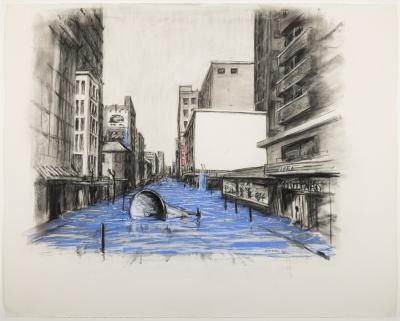

Sarindar Dhaliwal. Indian Billboard, 2000. Watercolour, oil pastel on paper, Overall: 127 × 153 cm. Collection of the Canada Council Art Bank. © Sarindar Dhaliwal. Photo: Brandon Clarida Image Services

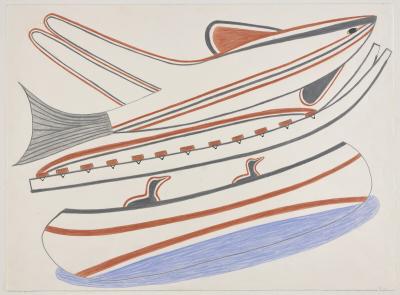

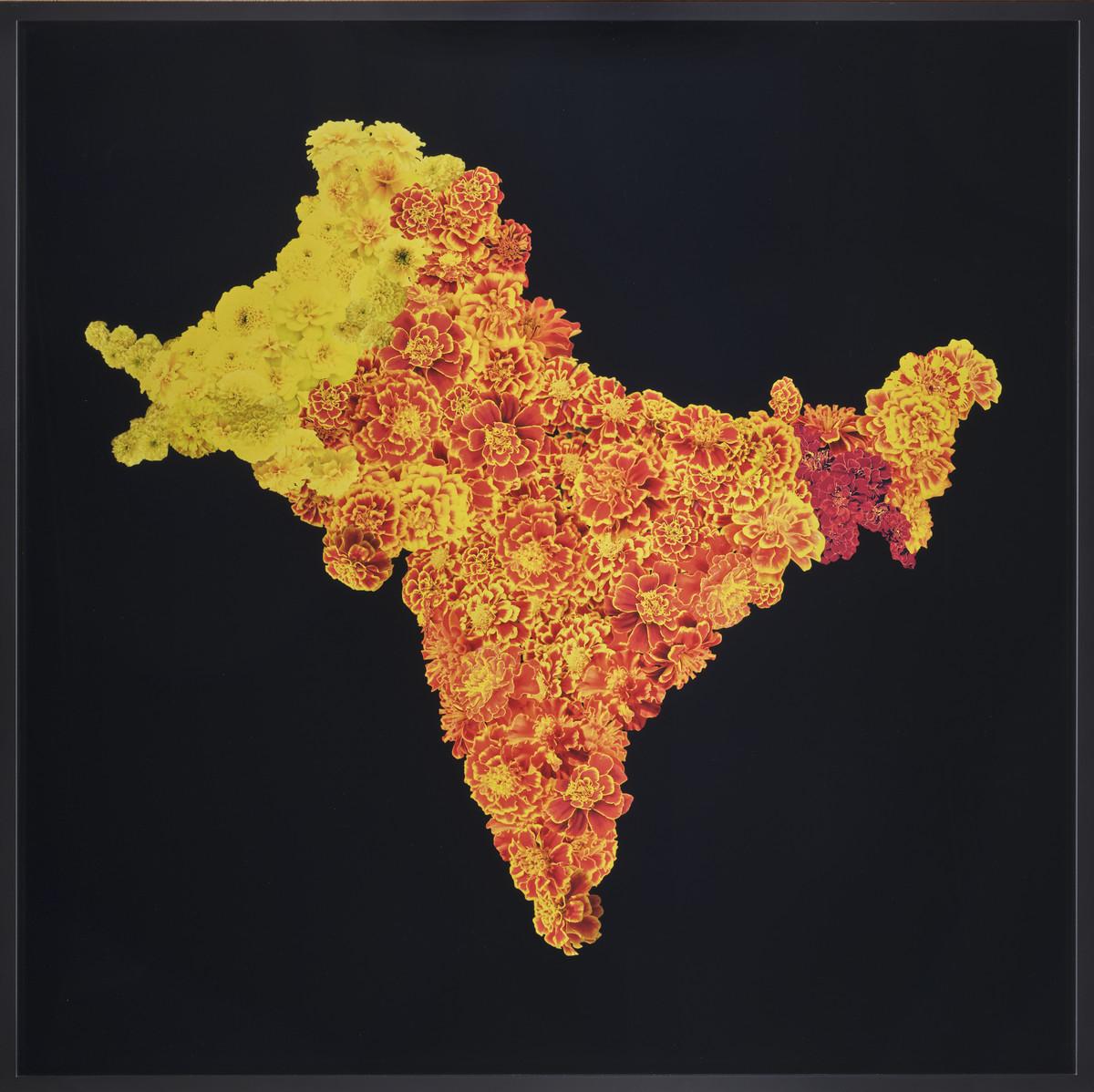

Foyer: The cartographers mistake: the Radcliffe Line is the first artwork in an ongoing series you began creating after you read Indian Summer, The Secret History of the end of an Empire by Alex von Tunzelmann. Could you share some of what you discovered in the book, and the conceptual meaning of the cartographers mistake series?

Dhaliwal: My work on this series began in the late 90s. There were two incidents that I was deeply affected by: One was the death of a 15-year-old girl on Vancouver Island named Reena Virk. She was of Indian descent and had recently been placed in foster care. One night she attended a party and was viscously attacked by another group of teens, thrown in the river, and tragically killed. The other was a seven-year-old boy named Randal Dooley. He had recently emigrated from Jamaica to Toronto to live with his father and stepmother. Randal was also tragically killed, due to the horrific abuse and neglect of his stepmother.

These events made me reflect on the idea of God, and wonder, “Where was God when Reena and Randal needed him?” So I began to do research into the afterlife, and reincarnation. I discovered that there was something called the Akashic Library. It is a metaphysical record of everything that has ever happened in the world, and it can only be accessed by those who can enter the non-physical plane. One of the only things that gave me comfort from the emotional distress I was feeling was the thought that there are two volumes in the Akashic Library dedicated to Reena Virk and Randall Dooley.

I continued to read heavily about life after death and reincarnation. Then in 2001, during my MFA, I read Indian Summer and discovered the story of Cyril Radcliffe. Though he was a barrister, in 1947 [when India and Pakistan won independence from Britain] he was employed as a cartographer sent by the British government to India. After being given unsophisticated maps and a very short timeline, Radcliffe was tasked with laying the partition between India and Pakistan [The Radcliffe Line]. After being pressured by India’s soon to be Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, Radcliffe granted the predominantly Muslim region of Kashmir to India rather than Pakistan – a decision that has caused war and political tension in the region ever since.

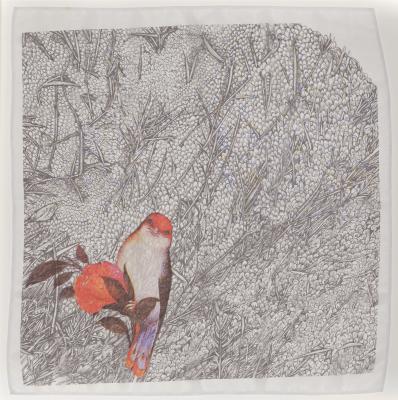

Then I got an idea that, as a punishment, Cyril Radcliffe – even though I don't consider him guilty – should get reincarnated as a bird, again, and again and again throughout time. So I wrote stories about him in his various disguises as birds, and the details and settings of the stories were dependent on where I was in the world. I did a residency in Sydney, and Cyril was a little baby cockatoo, and he remembered all his past lives as a bird.

There are 11 works in the series, of varying mediums. In them, I bring together my geographical wanderings. There’s a satisfaction I get from these retellings of history; a freedom to use my imagination and just make these kinds of weird, quirky works.

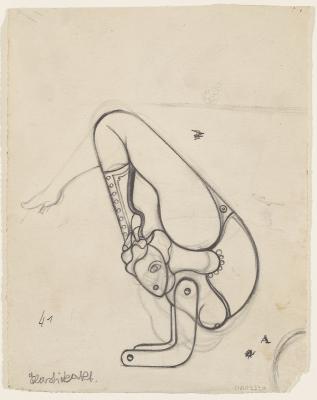

Sarindar Dhaliwal. the cartographer’s mistake: the Radcliffe Line, 2012. Chromira print, 107 x 107 cm. Collection of the Art Gallery of Ontario. Purchase, with funds by exchange from the J.S. McLean Collection, by Canada Packers Inc., 2020. © Sarindar Dhaliwal. Photo courtesy of the artist. 2019/2467.

Foyer: It's evident that your relationship to – and your memories of – India have greatly influenced your art practice. How do you think leaving as a child and not returning back until much later has uniquely shaped your artistic lens on India?

Dhaliwal: I think it's both India and Britain. I think it's the colours, flora and architecture of India that have shaped my artistic lens more than anything sort of deeper than that.

I think the first time I went back [to India] was around 1978. There is a work I made during that time that talks about going to India and looking for “the exotic”. At the time, I was travelling with a Dutch man, and I can remember walking around the botanical gardens with him. People were staring and pointing at us. I instantly realized that we weren't looking for the exotic, we were the exotic.

Sarindar Dhaliwal: When I grow up I want to be a namer of paint colours is on view now at the AGO on Level 1 in the Philip B. Lind Gallery (galleries 131 & 132).