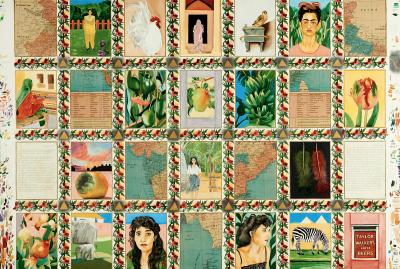

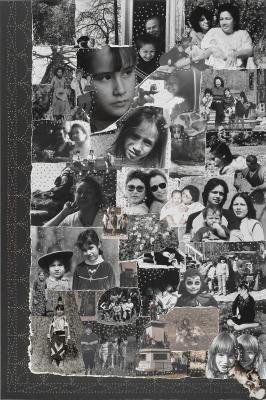

A Quickstop run with Tarralik Duffy

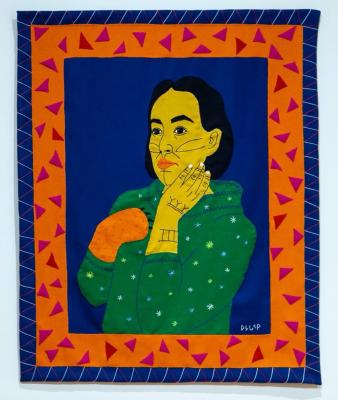

Multidisciplinary Inuk artist Tarralik Duffy talks about her solo show at the AGO

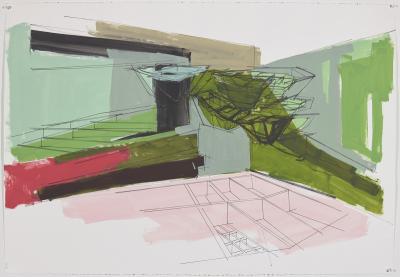

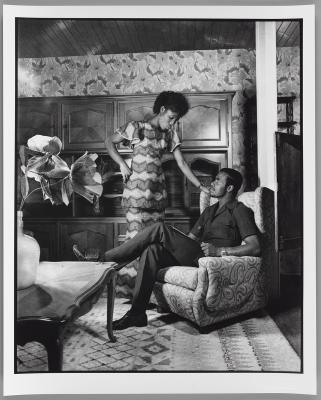

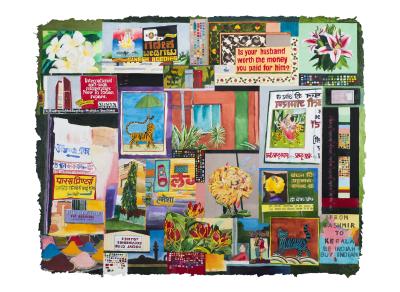

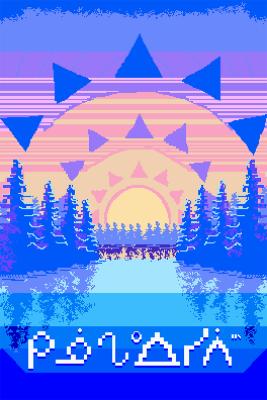

Installation view: Tarralik Duffy: Let's Go Quickstop, June 2023 - Ongoing. Art Gallery of Ontario. Artwork © Tarralik Duffy, Pipsi, 2022. Photo: AGO.

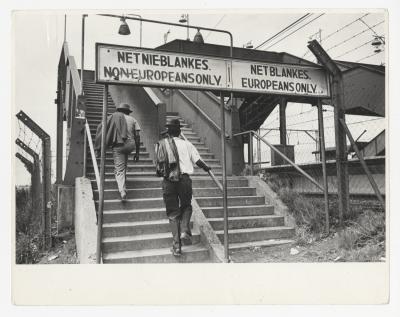

Writer, multidisciplinary artist and designer Tarralik Duffy’s work is a love letter to her hometown of Salliq, Nunavut. An intuitive connection to her Ancestors and a deep reverence for Inuit culture and tradition have informed her dynamic practice over the years – from jewelry making to large-scale soft sculpture. In her work, Duffy references objects from her own childhood that are iconic in Nunavut and embedded in Inuit contemporary culture.

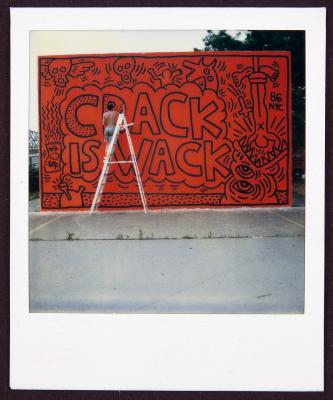

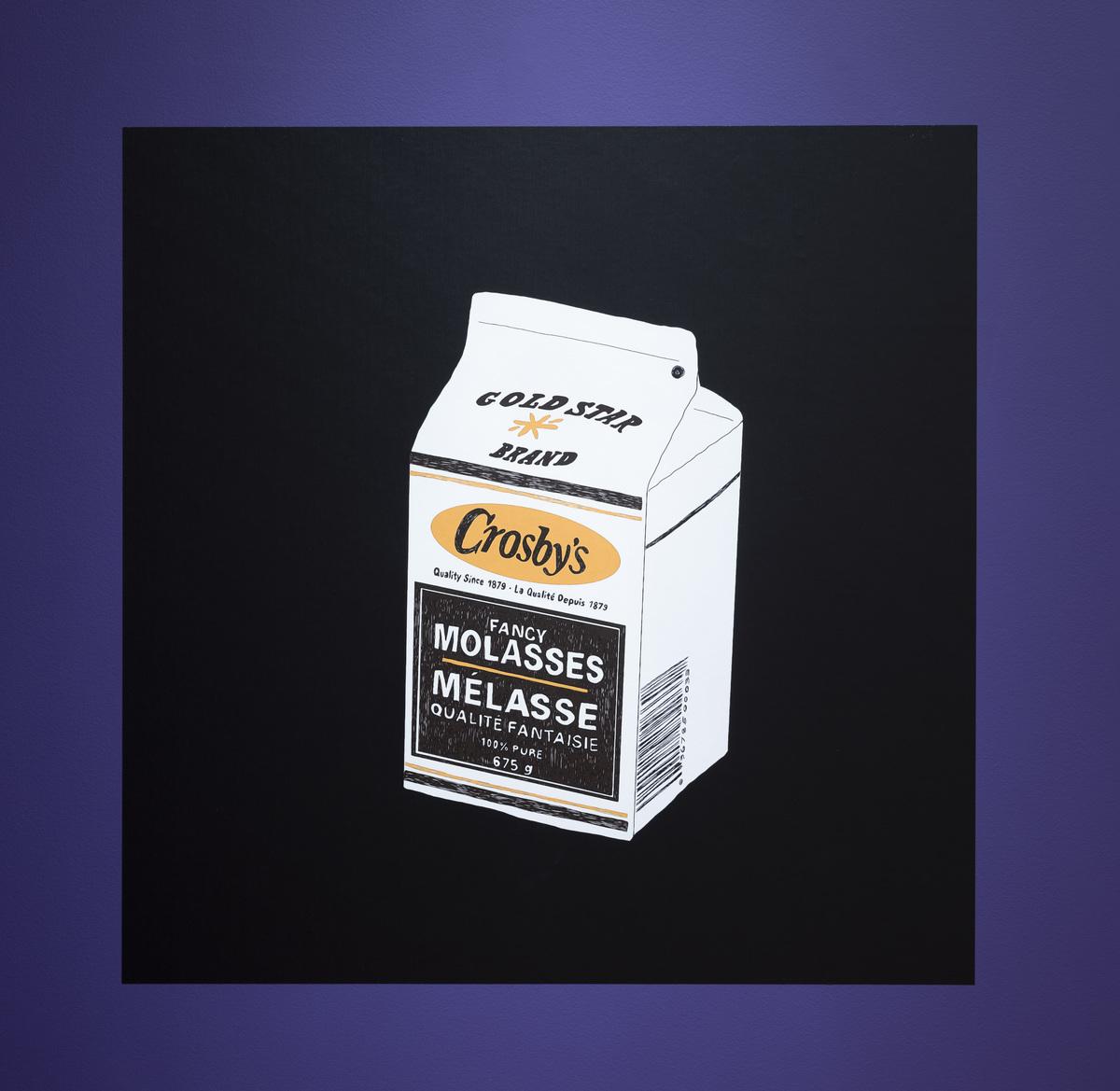

On June 16, 2023, her most recent solo exhibition – Let’s Go Quickstop – opened at the AGO. The title references a northern Canada convenience store chain frequently visited by Inuit communities for groceries, takeout and hunting/camping supplies. The exhibition of drawings and sculptural works features striking depictions of products that were for sale during Duffy’s childhood: cigarettes, China Lily Soya Sauce, Crosby’s Molasses, Magic Baking Powder, Pepsi Cola, and Red Rose Tea.

In conversation with Foyer, Duffy offers insight into the inspiration behind Let’s Go Quickstop, the profound impact of her grandmother, and the importance of community-based Inuit artists.

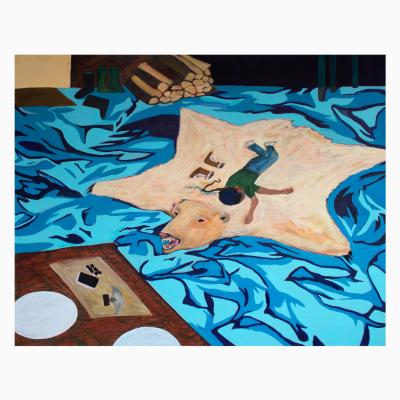

Installation view: Tarralik Duffy: Let's Go Quickstop, June, 2023 - Ongoing. Art Gallery of Ontario. Artwork © Tarralik Duffy, Crosby Molasses, 2023. Photo: AGO.

Foyer: The works in the exhibition feature kitchen pantry products found at Quickstop stores in Nunavut. Can you talk about what makes these items so iconic for you?

Duffy: I have a very specific memory of the look of the packaging of Crosby’s Molasses from the 80s. When I walked in to see the installation for the exhibition, I started crying because it was like looking at the molasses on my Anaanatsiaq's (grandmother's) table. I didn't expect to have such an emotional reaction to my own work, because I’ve seen it a lot, and I've already drawn it and conceptualized it. It’s very nostalgic to me, and it took me right there. When we lived in Nunavut, we would always visit my grandmother daily, and if she made fresh bannock, we would dip it in the molasses. Usually, there'd be a really messy molasses carton on the table and you pour it into a bowl. For me, the items are reminiscent of visiting my Anaanatsiaq’s house – or my mom's house. To me, they represent more than the store. I'm also a sucker for marketing – I like a well-marketed product. There's something so nice about items that have yellow, or black - I'm very drawn to things like that. They're very tied to my relationship to my Anaanatsiaq, and my mom, and visiting culture in Nunavut.

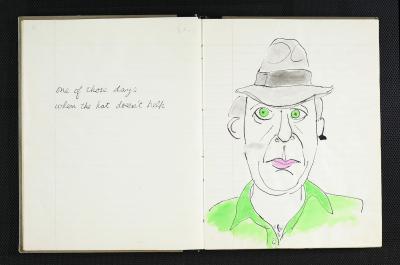

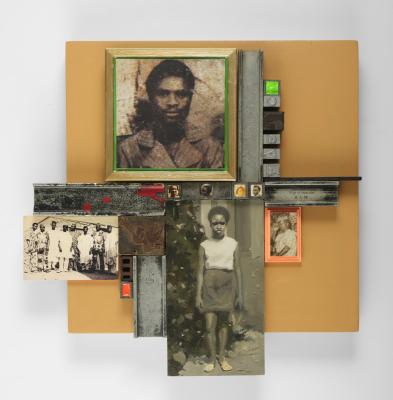

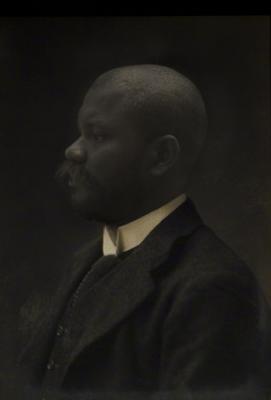

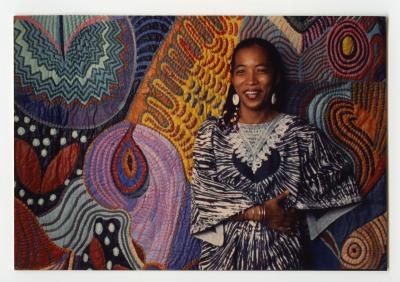

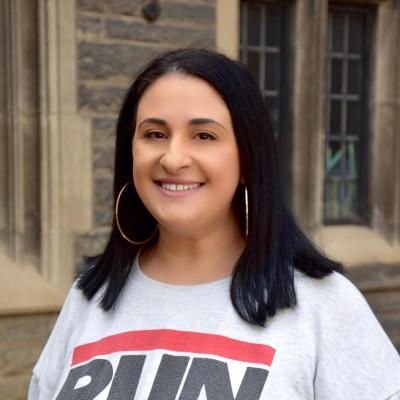

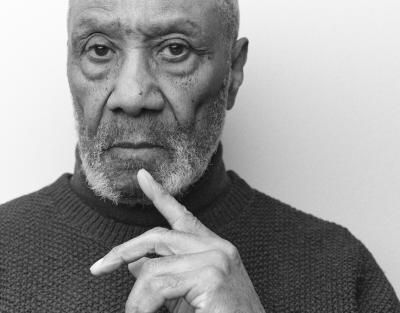

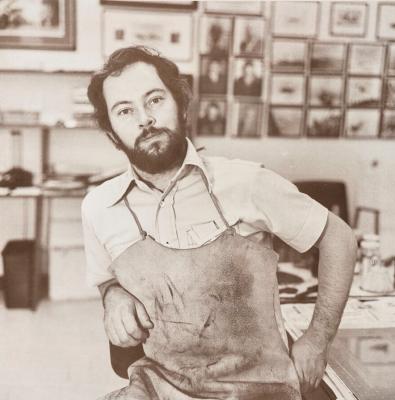

Tarralik Duffy. Photo courtesy of the artist.

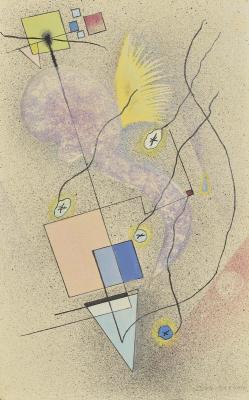

What has drawn you to this specific style of pop art? Are there any references or inspirations that you could share with us?

I think a lot of people probably initially think of Andy Warhol. But for me, one of my first inspirations – as far as drawing everyday items from Nunavut – is Annie Pootoogook. I bought a book of her drawings that featured food items and scenes of everyday life, and that was very moving to me. She's definitely one of my inspirations. And I do love Andy Warhol – though I kind of didn't like him at first – so now it's funny he’s the artist that I'm often compared to. I just liked the idea of everyday objects, in the past Inuit often drew things that they encountered daily, which is often animals, or what they saw out on the land. What I encountered every day growing up was going to the store, because that was the popular place to go. There was nowhere else to go really, except for the Hudson’s Bay or the Co-op – which was the inspiration for Let’s Go Quickstop. It's like, where else are you gonna go?

Installation view: Tarralik Duffy: Let's Go Quickstop, June, 2023 - Ongoing. Art Gallery of Ontario. Artwork © Tarralik Duffy, Klik Can, 2023; Pilot Biscuits, 2023; Northern Store plastic bags, 2022. Photo: AGO.

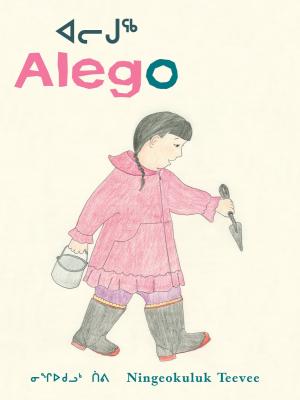

One of the other mediums that is central to your practice is jewelry making. Can you share how you got your start in jewellery making and some of the inception story of your jewellery brand Ugly Fish?

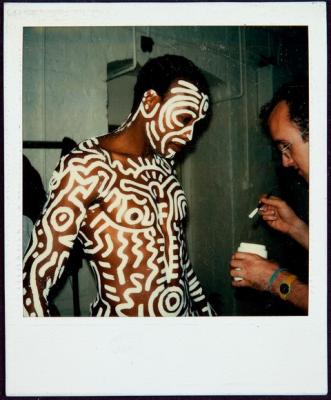

With the jewellery making, I was in a place in my life where I didn't know what to do with my time. I was visiting my sister, and we would draw a lot. I had these grandiose ideas of what I wanted to do with my time, but I would find that overwhelming. While I was visiting her I noticed there was discarded antlers around town. She also had a Dremel that no one was using on her porch. Then I started thinking, “if my ancestors had access to a power tool, what would they make with it?” So I asked my sister if I could use the Dremel, found some antlers and just started cutting antler pieces.

I was attracted to the idea of not wasting anything. It was born from this sense of needing something to do, and I loved the feeling of completing something in a day or a couple of hours; something that is right in front of me. That was really satisfying.

Then the practice grew from there. I'd go walking along the beach looking for materials. One day I found these two perfectly washed-up whale vertebrae; intervertebral discs right by my feet. They were a perfect pair of earrings just waiting for me like a gift. I had never seen anyone make earrings from whale vertebrae before, at least not in that way, but I thought that it would be beautiful. It’s inspired by the concept of not wasting anything, because I saw a lot of pieces going to waste, like antlers. I noticed ptarmigan feet would often be thrown away, so I started making lucky ptarmigan feet as a riff off of lucky rabbit feet. Our ancestors definitely didn't waste. We always say as Indigenous people, “we don't waste anything. We use every part of an animal”, which is bullshit, because today a lot is wasted. I've seen a lot of animals in the garbage and a lot of garbage on the land. There's a part of me that treats it a bit like repentance. I know I have wasted a lot in my life. Our generation still has a lot to learn from the past, and we need to go back to the way we used to treat animals. I go and salvage things and I turn them into something beautiful.

In Nunavut, we call Sculpins “ugly fish”. My Anaanatsiaq was named Kanajuq, which means sculpin in Inuktitut. So the name is an homage to my Anaanatsiaq.

Installation view: Tarralik Duffy: Let's Go Quickstop, June, 2023 - Ongoing. Art Gallery of Ontario. Artwork © Tarralik Duffy, Pop, Chip Kukuk, 2022. Photo: AGO.

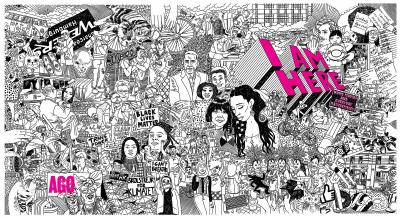

In recent years, the AGO has exhibited the groundbreaking work of Inuit artists like ᓛᒃᑯᓗᒃ Laakkuluk and Shuvani Ashoona, among others. What are your feelings about the popularization of Inuit art on a global scale? How do you hope to see it evolve in terms of opportunities and representation for Inuit artists?

I think because our culture is so rich, we have so much to work from. Our experiences are very deep. Inuit have a lot to share. We have a lot to express, and we have always been so artistic, so I'm not surprised by the popularity.

The Inuit artists that I've always been the most inspired by are community artists. Cost of living is so high, there are housing issues and materials and tools can be expensive, especially when poverty is a real issue. My friend Henry Nakoolak, for example, makes some of the most amazing carvings that he would sell to the co-op. Then they're resold for quite a lot, but he's never seen that money. I have many carvings from him, they are my some of my most treasured pieces. A few he gifted me and I would try to buy from him whenever I could afford it. There was one very cold winter where he lived in a shack, he borrowed power to carve, he never gave up even though he was facing extreme circumstances.

I can never remove myself from that understanding, because I feel quite privileged in a way. Especially when you're the kind of person that can live in white worlds, or worlds that aren't very Inuk. I would love to see artists like that being able to bask in the glory of their talents in a way that can be life-changing monetarily. So there's something about those carvers that I think about often.

Another one of my great friends – who recently passed away – is Daniel Shimout. He was an amazing carver, and I think he received a bit more recognition for his work, but not as much as he should have. I own his pieces as well and I cherish them greatly. It would be great to see artists like that be highlighted and have major shows, though I know Inuit culture and the art world are diametrically opposed. They’re like different universes. Sometimes it's positive, and sometimes it can be negative.

Installation view: Tarralik Duffy: Let's Go Quickstop, June, 2023 - Ongoing. Art Gallery of Ontario. Artwork © Tarralik Duffy, Pipsi, 2022. Photo: AGO.

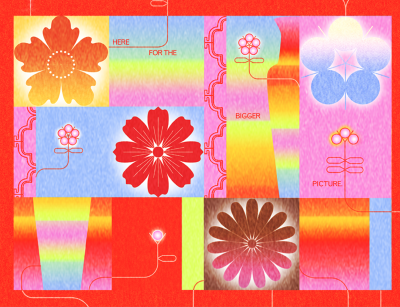

You're a prolific multidisciplinary artist. Are there any new projects or current works in progress that you could share details about?

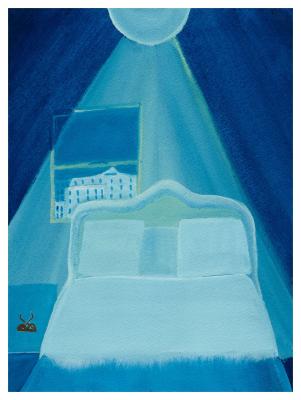

I've become obsessed with soft sculpture. So I have a show coming up in Winnipeg on September 22,2023 [closed April 2024]. That's going to be another exhibition where I’m taking 2D drawings that I've done and turning them back into 3D pieces. I love these sculptures because the sewing is physically taxing, and then you're holding onto an object afterwards. There's something about stitching that really connects to my ancestors. When we say ancestors, it often means something so far removed. When I say ancestors I mean directly to my Anaanatsiaq, my Amauq (great-grandmother), and my Aunties.

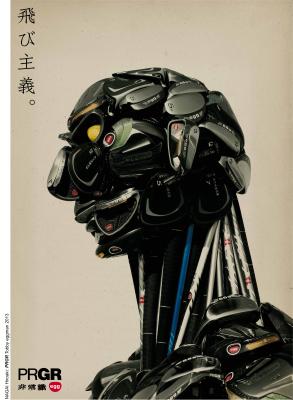

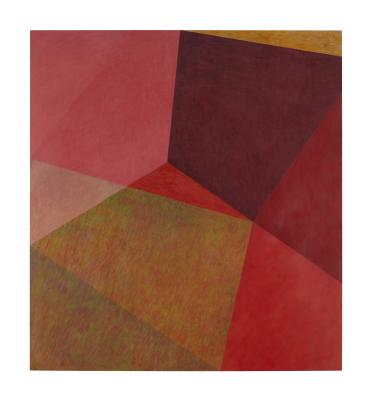

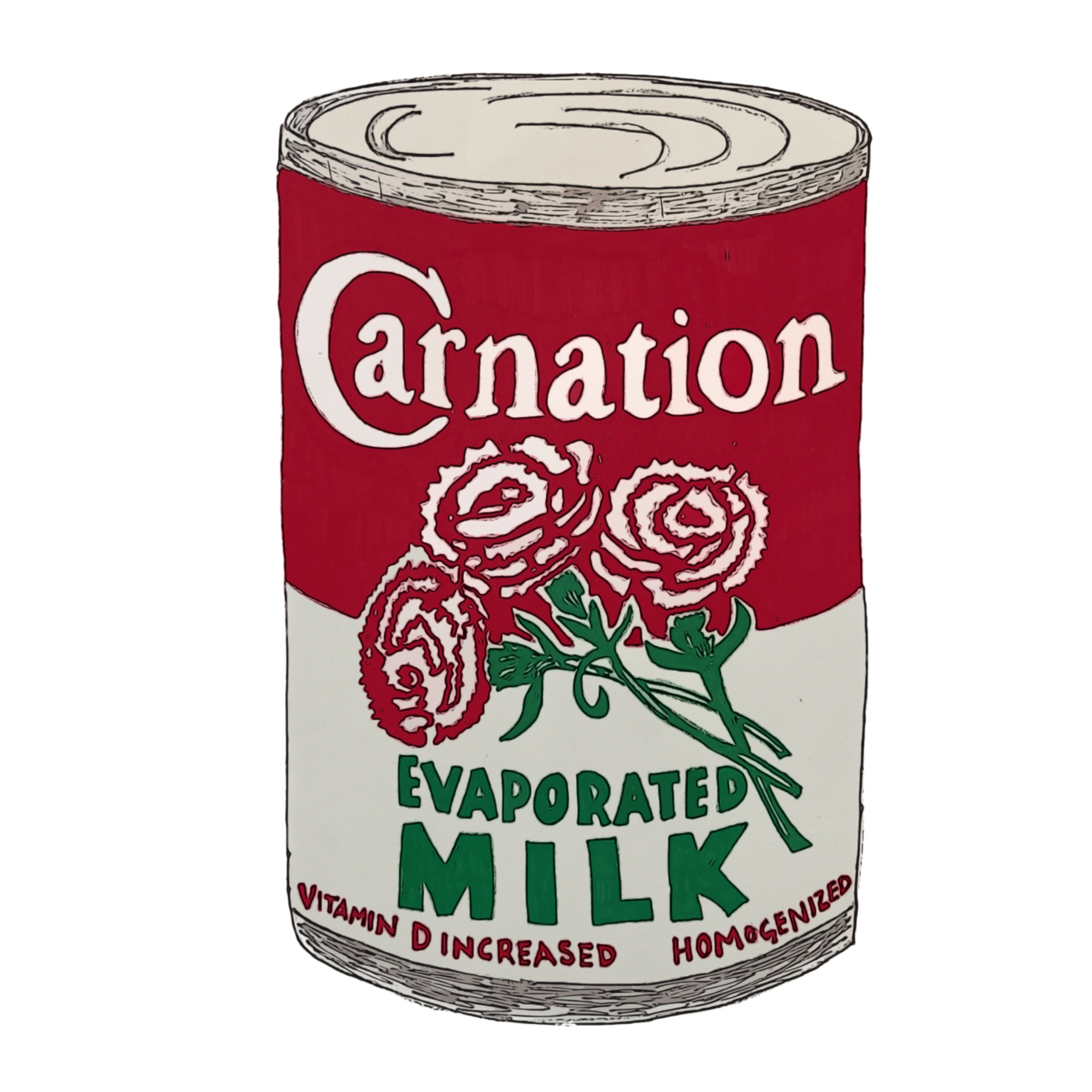

Tarralik Duffy, Carnation (2021). Digitized pencil drawing. Courtesy of the artist.

Tarralik Duffy: Let’s Go Quickstop is on view now on Level 1 of the AGO in the Fudger Rotunda (gallery 126).