Obituaries and couches

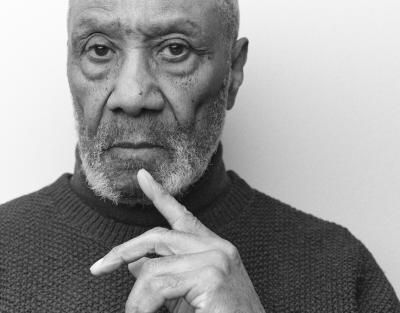

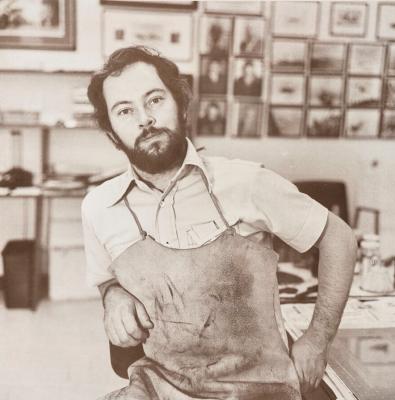

Acclaimed Canadian artist Ken Lum talks death, class, childhood, and sofas.

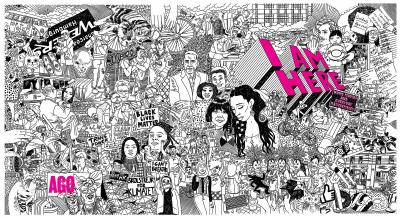

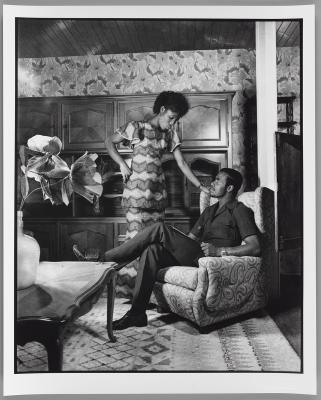

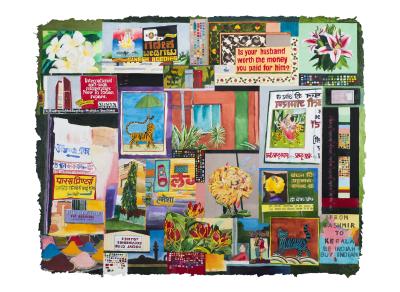

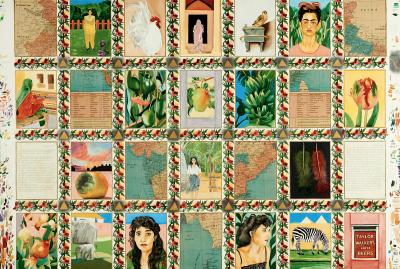

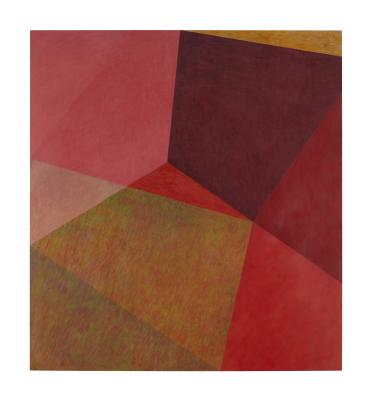

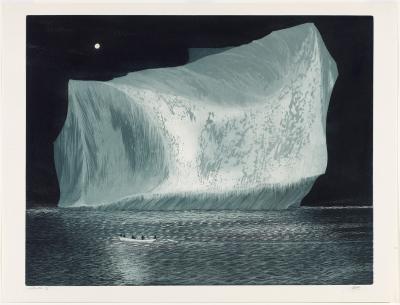

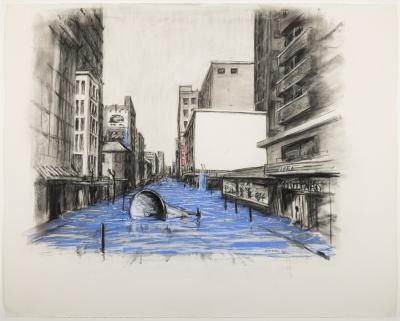

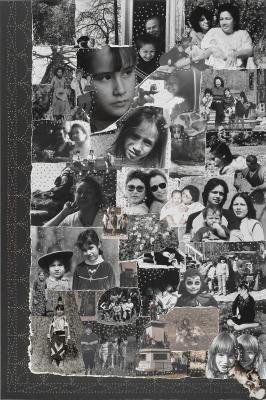

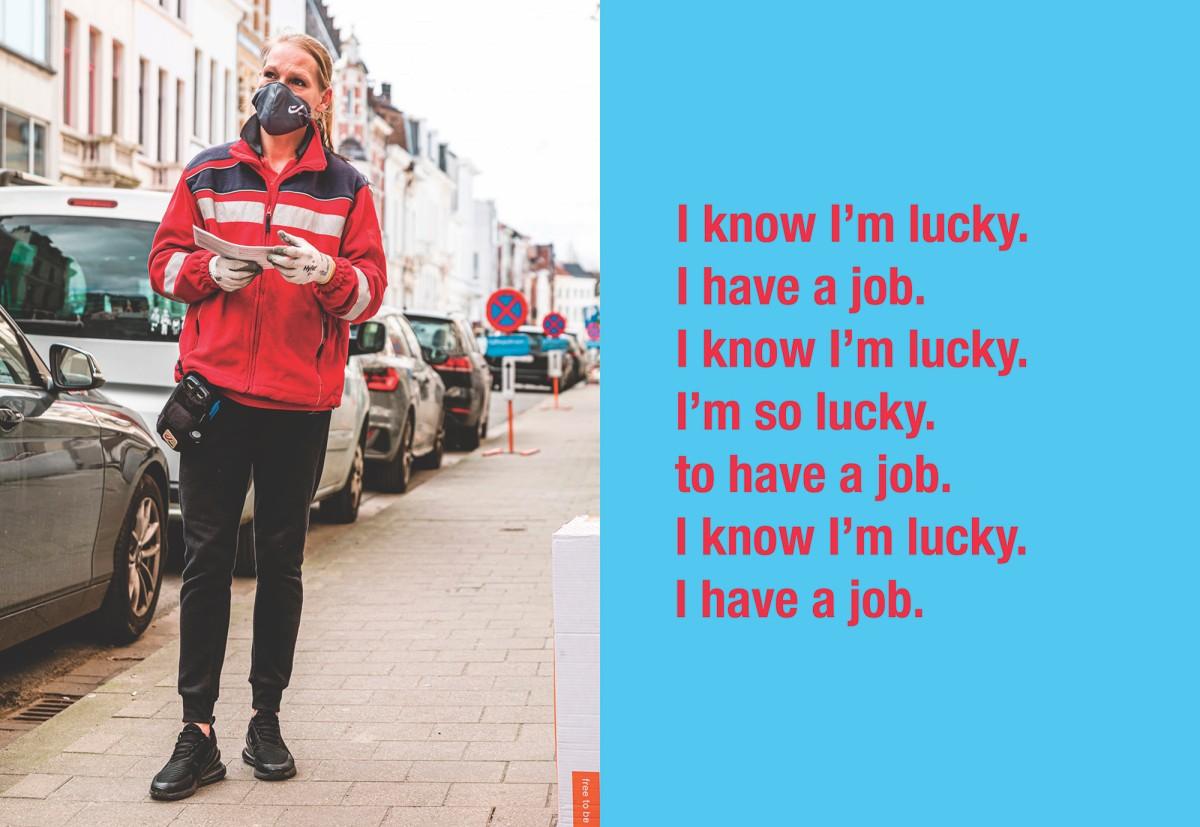

Ken Lum, I know I’m lucky. I have a job. 2021. Digital print on archival paper, 198.12 x 259.08 cm. Courtesy of Royale Projects and Ken Lum. © Ken Lum Image courtesy of the artist

Block of text on the right: I know I'm lucky. I have a job. I'm so lucky. to have a job. I know I'm lucky. I have a job.

In June 2022, AGO visitors witnessed the challenging and thought-provoking artworks of Death and Furniture – the debut AGO solo exhibition by acclaimed Canadian artist Ken Lum. Closed on January 2, 2023, visitors experienced this impactful career survey featuring works of sculpture, photograph, text and installation, spanning the last four decades of Lum’s practice.

On September 21, Lum appeared at the AGO for a conversation with Sofía Hernández Chong Cuy, Director of Kunstinstituut Melly, and Xiaoyu Weng, past AGO Carol and Morton Rapp Curator, Modern and Contemporary Art, about his work and the Rotterdam museum, Kunstinstituut Melly – which is named after his 1989 image-and-text piece, Melly Shum Hates Her Job. Check out their conversation below.

{"preview_thumbnail":"/sites/default/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/QO-rEbIFrV0.jpg?itok=EY-jAom8","video_url":"https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QO-rEbIFrV0","settings":{"responsive":1,"width":"854","height":"480","autoplay":0,"title_format":"@provider | @title","title_fallback":true},"settings_summary":["Embedded Video (Responsive)."]}

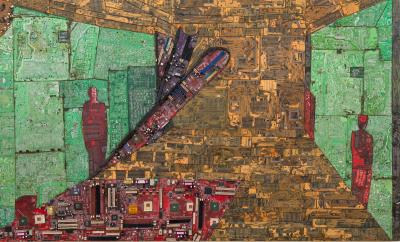

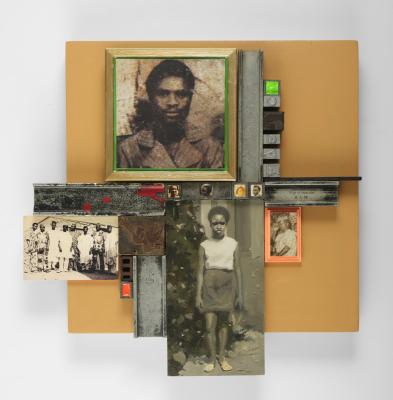

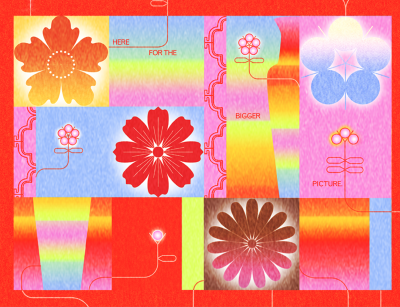

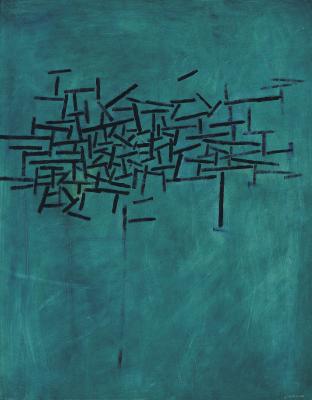

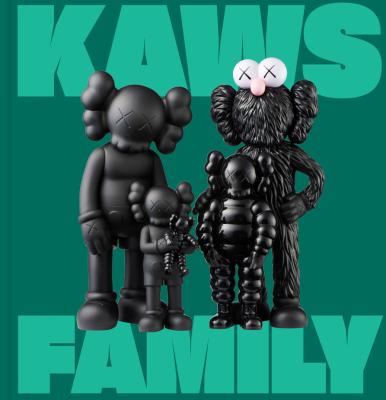

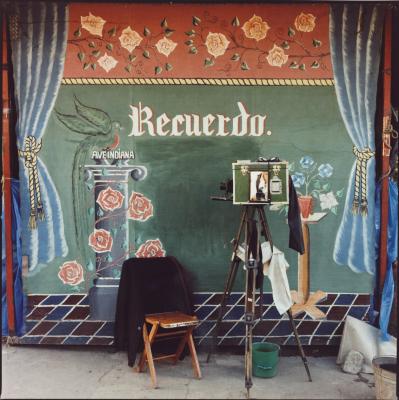

With Death and Furniture, Lum boldly explores the tensions between identity and representation, and challenges the systemic hierarchies of social power differentiated by race, class and gender. The exhibition features his newest body of image-and-text work, Time and Again, which zeroes in on how the pandemic exacerbated people's feelings of stress and anxiety in relation to labour. In addition, the exhibition includes works from Lum’s Necrology Series (2017 to present), Furniture Sculptures (1978 to present), and Photo-Mirror (1997).

Back in September, we connected with Lum and learned more about his approach to creation, and his ideas about death, class, childhood and sofas.

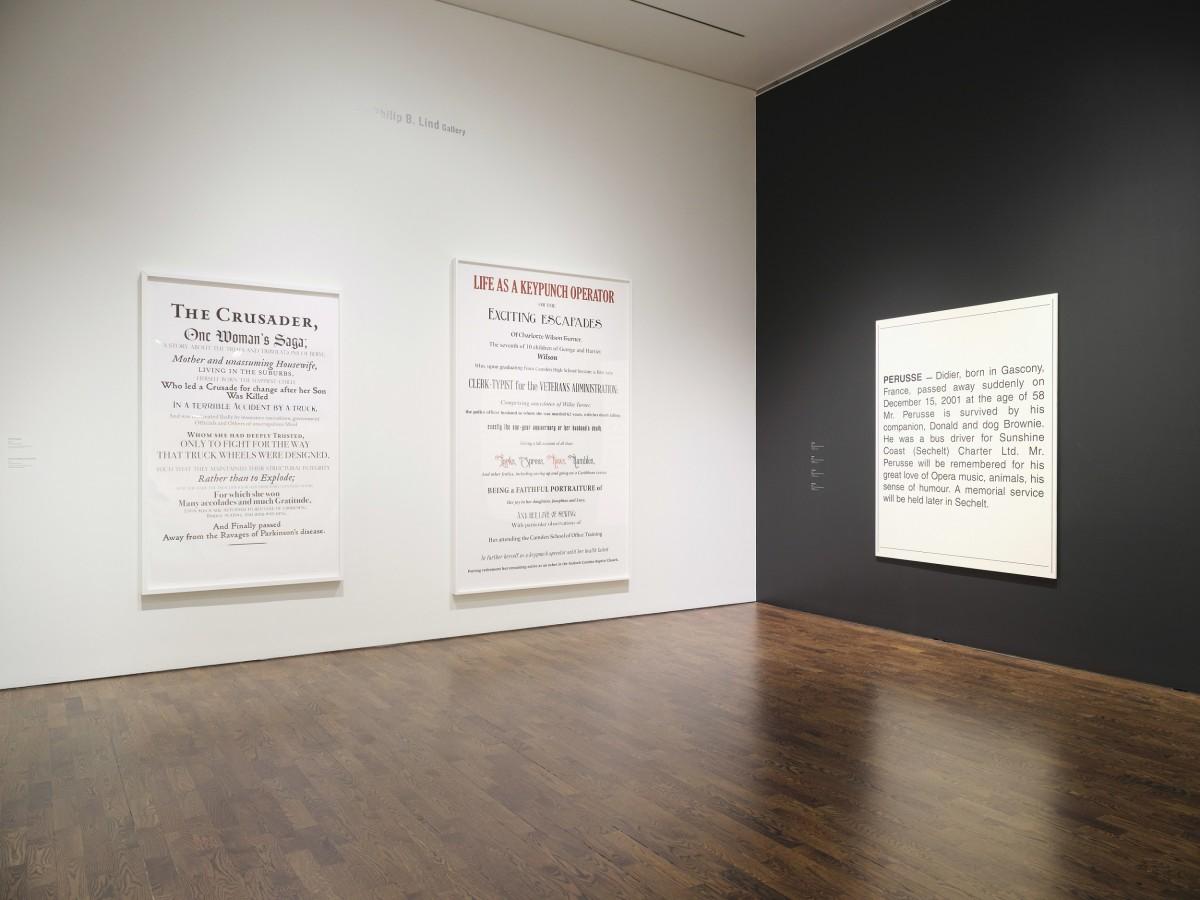

Foyer: Both Four French Deaths in Western Canada and Necrology place viewers in front of uniquely crafted obituaries. Can you elaborate on what interests you about the use of obituaries as a lens for examining human identity?

Lum: All my work dating back to the early 1980s is concerned with the question of how individuals come to be human subjects and how they enter into the process of social identity. I've always been interested in lives lived, and then in telling a story about each life. Whether through image-text, or portrait logo works, they're always about somebody. The viewer is offered indicators for reading the depicted or referenced person. A host of questions also open up such as who is this person? Why is that person in distress? Death is related to speculations of the other, because death is nothing if not a marker of a life lived. Death verifies life. Life and death are tethered terms. But my work is fundamentally about telling the story of a life and how that subject was constituted while alive.

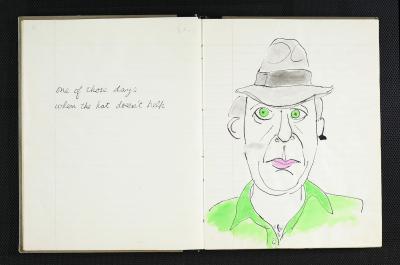

I don't see my fascination with death as a subject as a morbid interest. I have a lifelong habit of reading obituaries. For the Necrology works, the spark came from me coming upon a reprinted newspaper page on the occasion of the 150th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln's death. I noticed the unusual, from today’s perspective, relationship to kerning, font use and spacing of words. There were these sub-headers that in their summary provided a chapter heading narrative of the life of Lincoln. For example, a sub-header said “Born in a log cabin.” A later sub-header would be, “A young lawyer goes to Washington.” And the final sub-header read, “A nation mourns.” I thought, in their sequencing and aggregation, there is something poetic and beautiful in the odd overall design. I started thinking about the ways in which we imagine the world being so contingent on the aesthetic design of things. I started to think about how we not only gain in imagining by new aesthetic design but how we also lose imaginative possibilities once design principles become displaced.

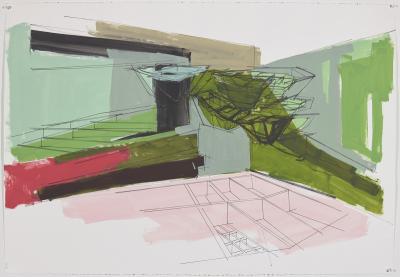

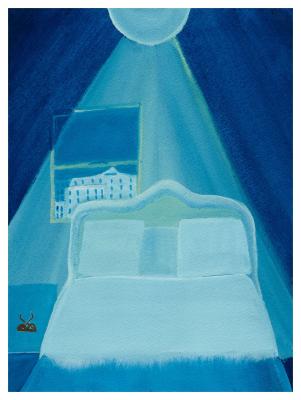

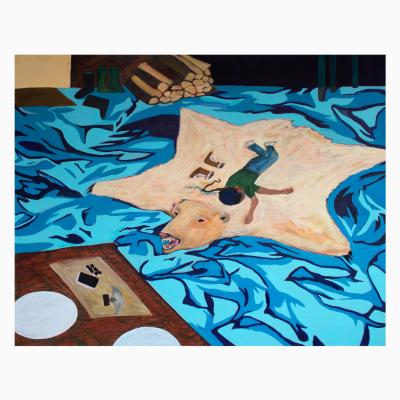

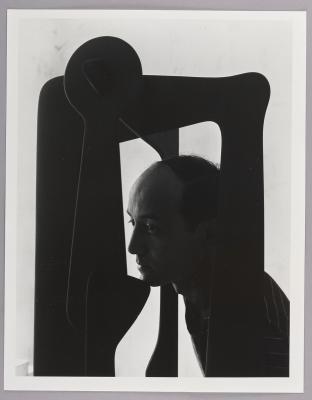

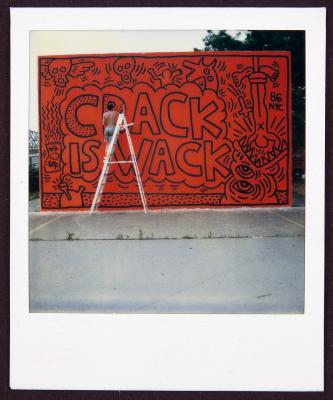

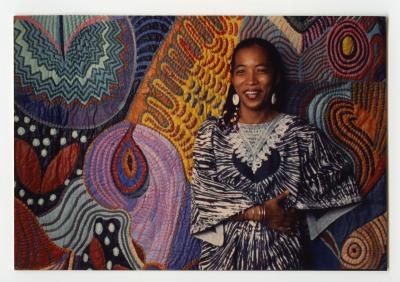

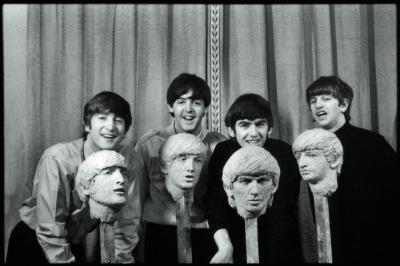

Installation view, Ken Lum: Death and Furniture, Art Gallery of Ontario. Artworks © Ken Lum. Photo: AGO.

Foyer: In Corners, Barriers and Corridors, sofas are positioned in ways that remove the function of seating. In your opinion, how does that alter the viewer’s perception or interpretation of the sofas?

Lum: I've long been interested in furniture because they have a mass and they occupy volume and space. These are the prerequisites of what makes a sculpture a sculpture. The furniture works rely on architecture or enclosure and they rely on circulation. Also, furniture has an anthropomorphic relationship to us because they're meant to be sat on and used; they have all the resonance of sculptural language, yet they exist as non-art, as implements of social spaces in the real world.

I also like how furniture transits into private space (like a collector’s home) and exhibition space. I like this idea of furniture as a kind of sculptural presence that is imbued with social economy, in the sense that it's imbued with questions of taste, questions of how much it costs, which evokes ideas of social differentiation in the form of economic classes. So cheap furniture looks like cheap furniture, and really expensive furniture – even if it's ugly – looks like really expensive furniture. They're commodities, and they're tailored for different classes of income.

A collector may buy something. For example, a collector bought two old loveseats I purchased at the Salvation Army store. The person is a major collector who has really nice, expensive, furniture, but then there’s these two old ratty loveseats perched in the corner. It's totally weird and I'm interested in this. I'm also interested in furniture because the logic of its configuration has an echo in minimal art. Avant-garde artists like Donald John, Robert Morrison and Dan Flavin were really into this idea of pure forms. There are many people who talk about the alienating effect of minimal art, because it's so familiar in a way and yet, it doesn't refer to anything. So I was interested in that dialectic because it is very much at the heart of Americanism.

Foyer: Your use of pink velvet sofas in the exhibition is a direct reference to your childhood. Can you talk about the process of drawing on your childhood (or your background) when creating your work? Is that something that you feel fuels a lot of your practice?

Lum: As a general answer, I believe making art is always about working out childhood trauma. Who am I? Why am I this way? What are my likes and dislikes, how did they come about? I like making art because it can address such questions without providing fixed answers. When I was a child, I often played with furniture sale flyers that would come in through the front door mail slot. They were often full of images for inexpensive furniture, but furniture nicer than what we had. The furniture was often staged within artificial settings [in the flyers], and lit by off-view lights. I loved these flyers. I loved looking at the furniture displays in old Sears or Eaton’s catalogues. In their totality, the pages upon pages of furniture for sale represented a system of representation for furniture. I would have fantasies of them decorating our home. I was perhaps six years old at the time.

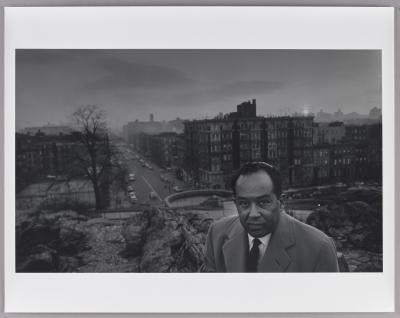

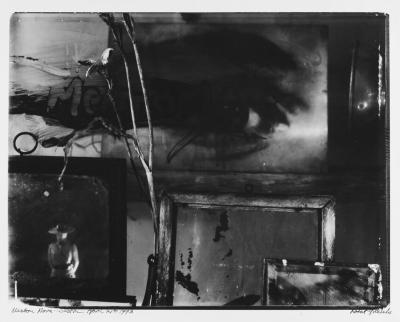

Installation view, Ken Lum: Death and Furniture, Art Gallery of Ontario. Artworks © Ken Lum. Photo: AGO.

Foyer: Much of your work has touched on the complex realities of labour and class. Time and Again zeroes in on how the pandemic exacerbated people's feelings of stress and anxiety in relation to labour. Could you share some of the inception story of Time and Again?

Lum: I was under discussion with the Middleheim Museum in Antwerp for about a year before the pandemic started, and I had a whole series of ideas for a show there. I went to Antwerp and scouted sites. Then when I came back home, the pandemic hit and Belgium was one of the worst-hit countries. By that time we'd already spent this certain amount of money, and Middleheim had been given a specific amount of money for my show. It's bureaucratic to say, but the money had to be spent – yet I couldn't go to Antwerp anymore, because Belgium’s borders were closed. So the question became, ‘How are we going to execute it?’ The whole thing ended up being done remotely with lots of Zoom meetings, images being sent by attachment, my annotating images and sending it back, etc.

Everyone had to respond to this strange new world of pandemic space and time. MFA students I was teaching at the time at the University of Pennsylvania were making work that I could not see physically but through the computer screen. Many students transformed their bedrooms into their studios and I would see their work in such contexts via Zoom. Everyone had to adjust to a different way of working and receiving art. In many ways, it was a reflection of luxury to be able to do that. Some people working in factories or at some fast-food outlet didn’t have such luxury. People who were poor, people tied to jobs essential to the society – they had to continue working from their workplaces. The theme of work and labour came out of these new conditions. It’s a theme that has always interested me, except this time it became quite acute. I had to change course and find a new way to make work, because I couldn’t be there.