Alanis Obomsawin is listening

Acclaimed Abenaki filmmaker and activist on her new exhibition and why she can’t stop making art

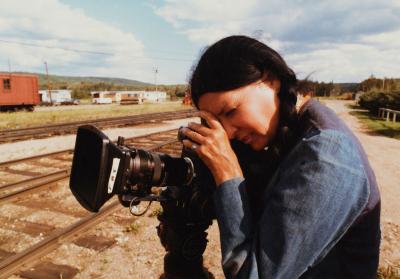

Alanis Obomsawin filming Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child, 1986. Courtesy of the National Film Board of Canada and the artist.

Surveying the remarkable life’s work of Abenaki filmmaker and activist Alanis Obomsawin, The Children Have to Hear Another Story, arrives this September in Toronto, following critically lauded presentations in Vancouver and Berlin. With more than 50 documentary shorts and features to her name, and countless awards and honours, one might assume her career was spent solely behind the camera.

Best known for the documentary films she has created during her long tenure at the National Film Board of Canada (NFB), Obomsawin’s body of work includes the groundbreaking ‘Incident at Restigouche’ (1984), a behind-the-scenes view of the police raids on a Mi'kmaq reserve, and ‘Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance’ (1993), documenting the Mohawk resistance to the expansion of a golf course on their sacred burial lands.

But as this exhibition so deftly proves, her accomplishments as a filmmaker are but one aspect of her activism. Since the 1960s, through music, art and education, Obomsawim has been a tireless advocate for Indigenous peoples and children, giving voice to those seeking basic rights and recognition. “Our people are so beautiful and I know that if you hear and see them, you will realize the knowledge they bring to the rest of the world.”

Ahead of the exhibition opening at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto, we listened to Obomsawin about what it’s like to see one's life work laid out, and why, at 91, she feels compelled to continue to witness and share stories.

The following has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Foyer: That a survey of Canada’s foremost Indigenous filmmaker should debut in Berlin is surprising. Or is it? What was the reception like there?

Obomsawin: Very surprising. I had been to Berlin a few times but had no idea there would be that kind of interest. Co-curator Hila Peleg initially proposed the exhibition. She and co-curator Richard Hill, and now Barbara Fischer at U of T, have all been so very generous. When it opened in Berlin they asked me, “What thing could we do to please you for something extra?”

I said, my main interest is really children. So they organized a group of children, about 15 of them, to come to the exhibition. And they were all refugees, and they were just beautiful, it was such an honour to meet them. I always show games to children, play with them, and tell them stories and songs. It was funny - I showed them a variation on ‘Duck, Duck, Goose’ called ‘Wild Duck’, where one person taps and another must run. So we did this, and at one point, I got picked, and would you believe I could not get up? It was so funny. Some people had to come in and help me up. This is the strong message there but I haven’t changed my game. Everybody was laughing. But the real highlight of these meetings is listening. The children talk to me about themselves. We met with children again at the Vancouver Art Gallery when the exhibition opened there, and I’m looking forward to doing so here in Toronto.

Foyer: What guides your decision-making process as an artist? How do you decide which projects, which stories to tell?

Obomsawin: I spend a long time listening before doing and ending any film project. I need to make sure that I really understand why people are saying what they are saying, and what it is about. I record a lot of audio, before turning on the camera. For me, that's what is sacred - the voice of the people. Their words are sacred. I can listen and listen again. If someone repeats themselves, it's okay, because by the time you're in the cutting room, if you have the same story three times, then you pick the best one. The sound of a voice conveys so much. When someone says something sad their voice changes to a different space. Sometimes they cry. Or sometimes it's funny, and they laugh, because they are at ease, and they trust. And those words are sacred. A lot of people say, “oh, no, I don't want to just do the voice. I want the camera”. Well, the camera is very important. But you have to listen and hear first, the secret of their life.

Alanis Obomsawin, Trick or Treaty?, 2014. Digital video, colour, sound, 85 min. Courtesy of the National Film Board of Canada.

Foyer: Few of us have the opportunity to see our life's work displayed. In seeing the exhibition, has anyone film, or object, or moment, stood out to you being, in hindsight, as particularly poignant?

Obomsawin: It's hard to say. There are interviews from when I was very young, and was subjected to racist comments - I remember a man telling me I was very lucky to be off the reserve. Of course, I defended myself as best I could at the time, but I didn’t have the language or experience I do now. I find that embarrassing to see, but it was like that then. Instances like that - which were not uncommon - are why the exhibition is called The Children Have to Hear Another Story.

Foyer: You’ve been witness to so much. Are there films or people you wish you could revisit?

Obomsawin: I don't have much time to look backwards, because I'm always working on a film. But when I do see my work - often at a film festival or screening, I always feel so moved by it. So many of the people I worked with - who fought so hard, and sacrificed so much - have passed away, and I feel my heart getting very, very sad. That makes me miss them more. But, at the same time, I say look at the magic. Yes, they're gone, but you can still hear them and see them and I find that very enriching.

When All the Leaves Are Gone, 2010. digital video. 17:30 min, Alanis Obomsawin, provided by the National Film Board of Canada. Filming Locations: Odanak and Trois-Rivières, Québec.

The Children Have to Hear Another Story is organized by Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin, Art Museum at the University of Toronto and the Vancouver Art Gallery, in collaboration with the National Film Board of Canada and through the generous support of Canada Council for the Arts and CBC/Radio Canada. It has been made possible in part by the Government of Canada.

Curated by Richard Hill, Smith-Jarislowsky Senior Curator of Canadian Art at the Vancouver Art Gallery, and Hila Peleg, The Children Have to Hear Another Story: Alanis Obomsawin is on view at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto from September 7 through November 25, 2023. For more information, visit the Art Museum at the University of Toronto's website.

![Attributed to Andrea Susan. [Susanna standing in the road], October 1964.](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-03/AGOCasaSusanna121886WebandStandard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=wIAUCJJ5)