LaBruce’s Queercore legacy

Renowned multidisciplinary artist Bruce LaBruce boldly traverses film, photography and porn.

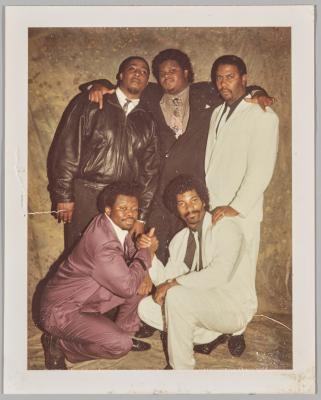

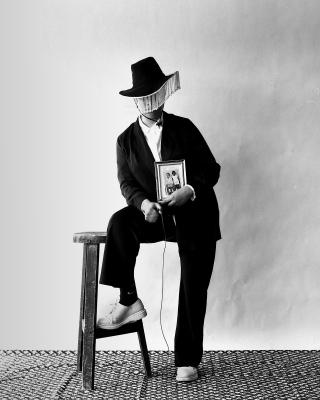

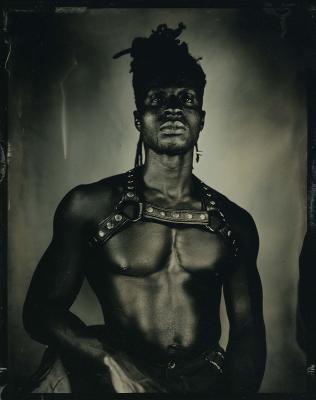

Bruce LaBruce by George Nebieridze.

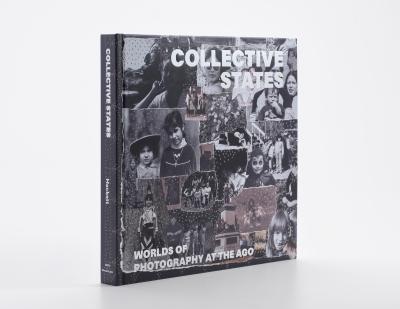

Recently, the multidisciplinary artist, cultural icon and inventor of Queercore Bruce LaBruce appeared live at the AGO. In a conversation with AGO Program Curator, Performance and Live, Bojana Stancic, LaBruce discussed his recent photography books Death Book and Photo Ephemera, as well as his cultural legacy and art practice at large.

After the talk, we caught up with LaBruce to ask some additional questions about photography, film and his artful approach to porn. Then we tapped Stancic - a devoted fan whose admiration for his work grew concurrently with her coming of age in Toronto - to put together a forward for the interview. Check it out below.

Forward by Bojana Stancic

Bruce LaBruce is a singular artist. He is a writer and ideologue, filmmaker and cineast, photographer and pornographer. While known primarily for his film work, his columns for the widely circulating free newspapers Eye Weekly and Exclaim! made him the voice of an alternative and youthful Toronto during their run, influencing and inspiring generations of teenagers, of which I was one. His prose was diaristic, intellectual and sexy, but also cosmopolitan - a narrative thread that connects all his artistic outlets. Amongst his many legacies of which I count Feelings and BLAB columns, Labruce has also been credited with inventing the queercore movement, a merging of queer and punk ethics and aesthetics. His DIY zine J.D.s was one of the first signals of this cultural paradigm announcing LaBruce to the world, and was also the one that led him into filmmaking. Since then, along with a number of short films, he has written and directed fourteen feature films, including Gerontophilia, which in 2013 won the Grand Prix at the Festival du Nouveau Cinema in Montreal, and Pierrot Lunaire, which won a Teddy Award at the Berlinale in 2014. His recent film Saint-Narcisse was named one of the top 10 films of 2021 by John Waters in Artforum, and his first feature No Skin Off My Ass was named a favourite by none other than Kurt Cobain.

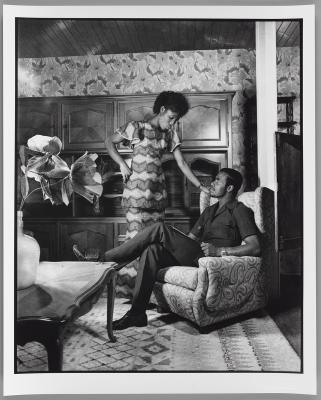

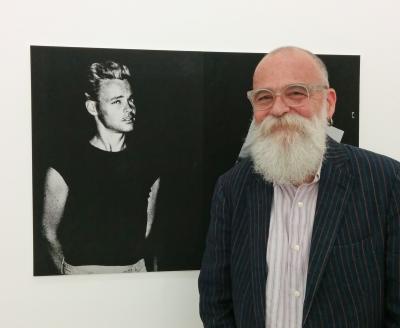

As a photographer LaBruce has had numerous gallery shows around the world, including Obscenity (2012) at La Fresh Gallery in Madrid – which caused a national ruckus in Spain – as well as C A S S T L in Antwerp, a non-profit artist initiative surrounding revered painter Luc Tuymans and his partner. Prior to our interview, Bruce just came back from London, UK where his work was featured in no less than three exhibitions, most notable being the blue chip Sadie Coles HQ where he was featured in a group exhibition aptly titled Hardcore. His artwork has been represented by Peres Projects, and his film work was rewarded by major retrospectives at TIFF Bell Lightbox in 2014, MoMA in New York in 2015, and la Cinémathèque Québécoise in Montreal in 2022. Closer to home, in addition to having a portrait in the current Wolfgang Tillmans To Look without Fear exhibition, it was an absolute honour for him to accept my invitation in 2016 to guest-curate AGO’s Pride-themed First Thursdays event, aptly named Queer Insurgents – which indeed he continues to be an emblem for, and a very prolific one at that.

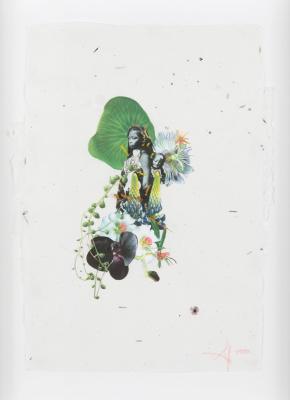

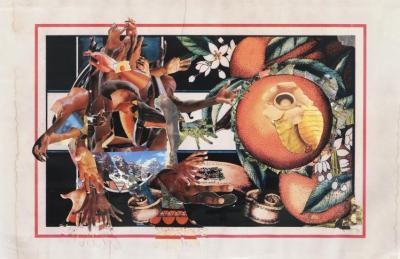

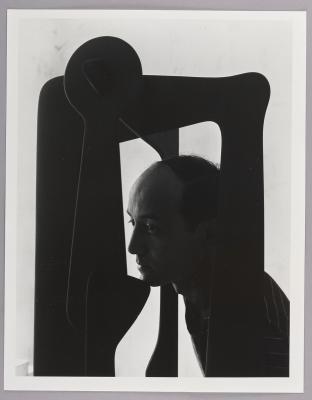

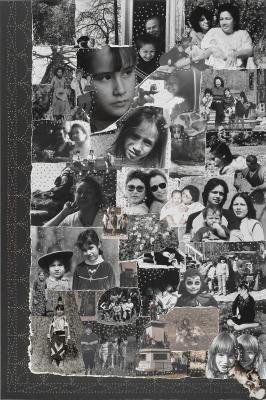

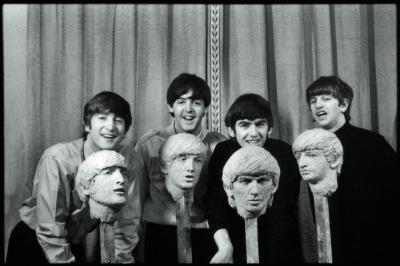

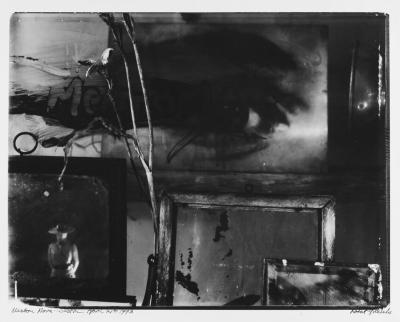

Image courtesy of Bruce LaBruce.

Foyer: Photo Ephemera features such a broad range of moments of your life. Can you walk us through your process for deciding what to photograph and when? Is it mostly intuitive, or are you usually looking for something particular?

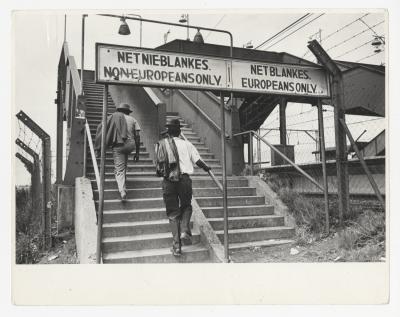

LaBruce: The photographs in my two volumes of Photo Ephemera were taken with a point-and-shoot digital camera that I switched to from a point-and-shoot film camera, somewhere in the early oughties, before the smart phone reversible screen camera became ubiquitous. I would carry my point-and-shoot in one pocket and my cell phone in the other. But the point-and-shoot was still a traditional style camera, with both a screen and a viewfinder, and you couldn't reverse it to take selfies. So taking photos with the point-and-shoot through the viewfinder entailed framing and composition, and, at least for me, represented a more deliberate and conscious act of photographing subjects. But it will still casual and spontaneous, so on my international trips I was constantly documenting the people I encountered - friends, hustlers, strangers, people in bars or on the street - as well as landscapes, buildings, signs, graffiti, etc. I had quite an archive of these photographs, so it was just a matter of going through as much of it as I could and choosing the most interesting ones, both aesthetically and in terms of the subject matter, much of which was very personal. While travelling I'm always looking for subjects, animate or inanimate, that are somehow emblematic of the country I'm visiting, often choosing more working class subjects in places that are off the beaten track, avoiding touristic sites that have already been photographed to death.

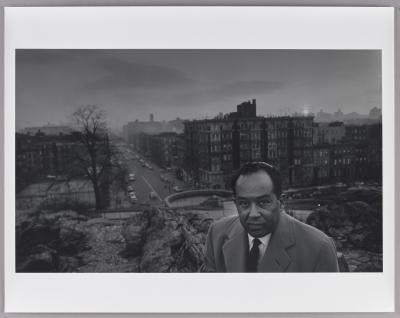

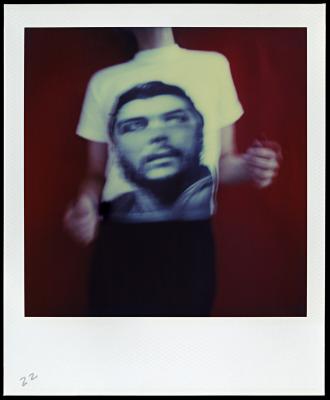

Image courtesy of Bruce LaBruce.

Foyer: You are both a prolific filmmaker and photographer. What are some of the key differences in your creative approach to each of these mediums?

LaBruce: I started out in film school at York University taking production. The first year included a still photography course where I learned proper darkroom techniques, and the second year was super 8 film production. So for me the two disciplines were equally important and interrelated in terms of developing a personal style and aesthetic, learning about depth of focus and composition and lighting and so on. I switched to Film Theory and got my Masters in Film and Social and Political Thought, but meanwhile I started producing a queer punk fanzine called J.D.s, which begat the Queercore movement, a very multi-disciplinarian project that involved taking photographs, making experimental super 8 films, desktop DIY publishing, collage, cut-and-paste, writing fiction and manifestos, etc. So for me, everything comes from the same creative source. A lot of the photography I've done is portraiture, starting in the late nineties when I shot naked guys with hard-ons for several NYC porn magazines like Honcho and Inches. But I also do fashion photography, and I take production stills on all of my movie sets, which is all part of the same process.

Foyer: A lot of your work boldly removes the barrier between photography and pornography. What do you find most inspiring about creating erotica?

LaBruce: During my queer punk period in the mid to late eighties and early nineties, along with a few friends, we rejected the mainstream gay world and turned to the punk movement, which seemed more stylistically interesting and politically rambunctious and radical. When we discovered that the punk scene exhibited the same misogyny and sexism as the gay scene, with the added bonus of homophobia, we decided to make our fanzine pornographic, queering punk in a very overtly pornographic way as a political statement: if you're so radical, you should be able to handle explicit gay sex and be more sexually revolutionary. We used found porn at first, and then I started making my own naive pornography on super 8, which eventually led me to becoming a full-fledged pornographer. I don't really make much of a distinction between pornography and art; for me it all comes from the same place. My work is often about exploring taboos and fetishes and pushing the limits of representation. If get the feeling that I've gone too far, or that I've even shocked myself, it's an indication that I'm going in the right direction. As the character Big Mother says in my movie "The Misandrists," "pornography is an act of rebellion against order and regulations. It expresses a principle inherently hostile to society." When I make more mainstream films or photography, I try to push it close to the boundary of pornography, and likewise, when I make porn, I try to introduce elements of narrative, irony, and aesthetics that are more associated with art practice.

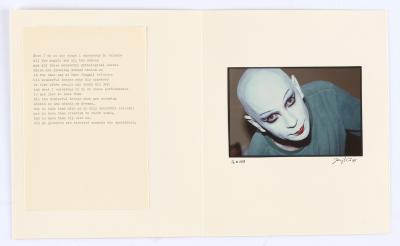

Image courtesy of Bruce LaBruce.

Foyer: Why do you think there is such a lack of art-forward content in the porn world?

LaBruce: For me the more pertinent question is why there is such a lack of porn-forward content in the art world! But both are interesting questions. I have been heavily inspired by pornographers of the seventies who are now considered masters of the avant-garde - Wakefield Poole, Peter de Rome, Fred Halsted, Peter Berlin, etc. A lot of seventies porn, which was all shot on film, was more experimental in form and "artistic," and the narratives and subjects of the films were more sophisticated and central to the experience of pleasure. Today, there is a lot of very interesting queer pornography that has this same quality and intent, and there is more crossover with art and fashion, but the barriers are still in place. My work has always been too pornographic for the art world and too artistic for the porn world. It's that grey area that fascinates me. The naked sexual act, with penetration, is still the greatest taboo in mainstream culture and art, and people who make "art films" tend to only use explicit porn if it is perceived as either something grotesque or unpleasurable, or demeaning. Sexual pleasure itself is taboo, but we are encouraged to take pleasure in the most obscene and horrifying acts of violence imaginable. I've explored this fetish for sexualized violence in a number of my films and in my recent photography book Death Book.

Image courtesy of Bruce LaBruce.

Foyer: Do you have any upcoming projects – photography, film or literature – that you are able to share any details about?

LaBruce: I recently shot an experimental art porn film at an art space in London, UK, called a/political. It's a porn reimagining of Pasolini's film Teorema, called The Visitor. I have some reshoots to do this summer as well as editing and post-production, and then we plan to debut it a/political, along with some of the props and the productions stills I took, for a month-long show in October during Frieze. I also have a new book of photographs coming out, title TBD, from Baron Books, which is more of a retrospective of my photographic work.

![Unknown photographer, Chillin on the beach, Santa Monica [Couple on beach blanket]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-04/RSZ%20WMM.jpg?itok=nUdDiiKr)