On Resting in the Dark While Developing

Black Pen writer Adeola Egbeyemi's response essay to What Matters Most: Photographs of Black Life.

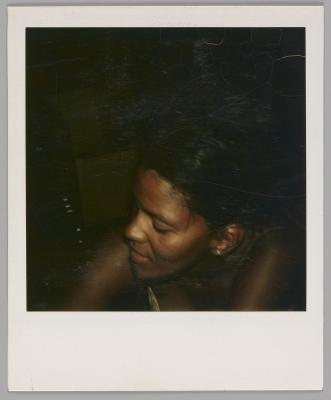

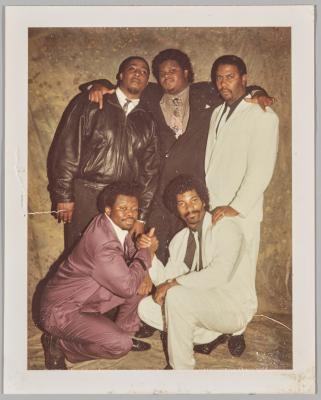

Unknown photographer. [Profile of woman with a stud earring and bare shoulders], 1974. Colour instant print [Polaroid SX-70], overall: 10.8 × 8.8 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Fade Resistance Collection. Purchase, with funds donated by Martha LA McCain, 2018. © Art Gallery of Ontario 2018/3547

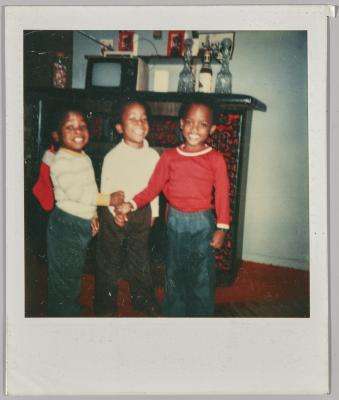

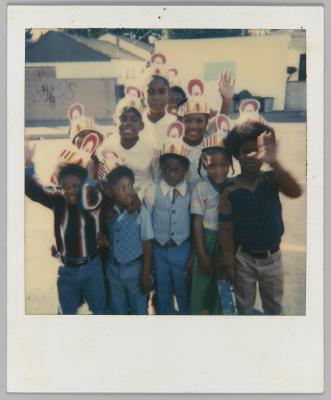

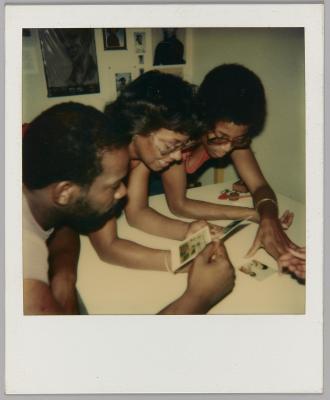

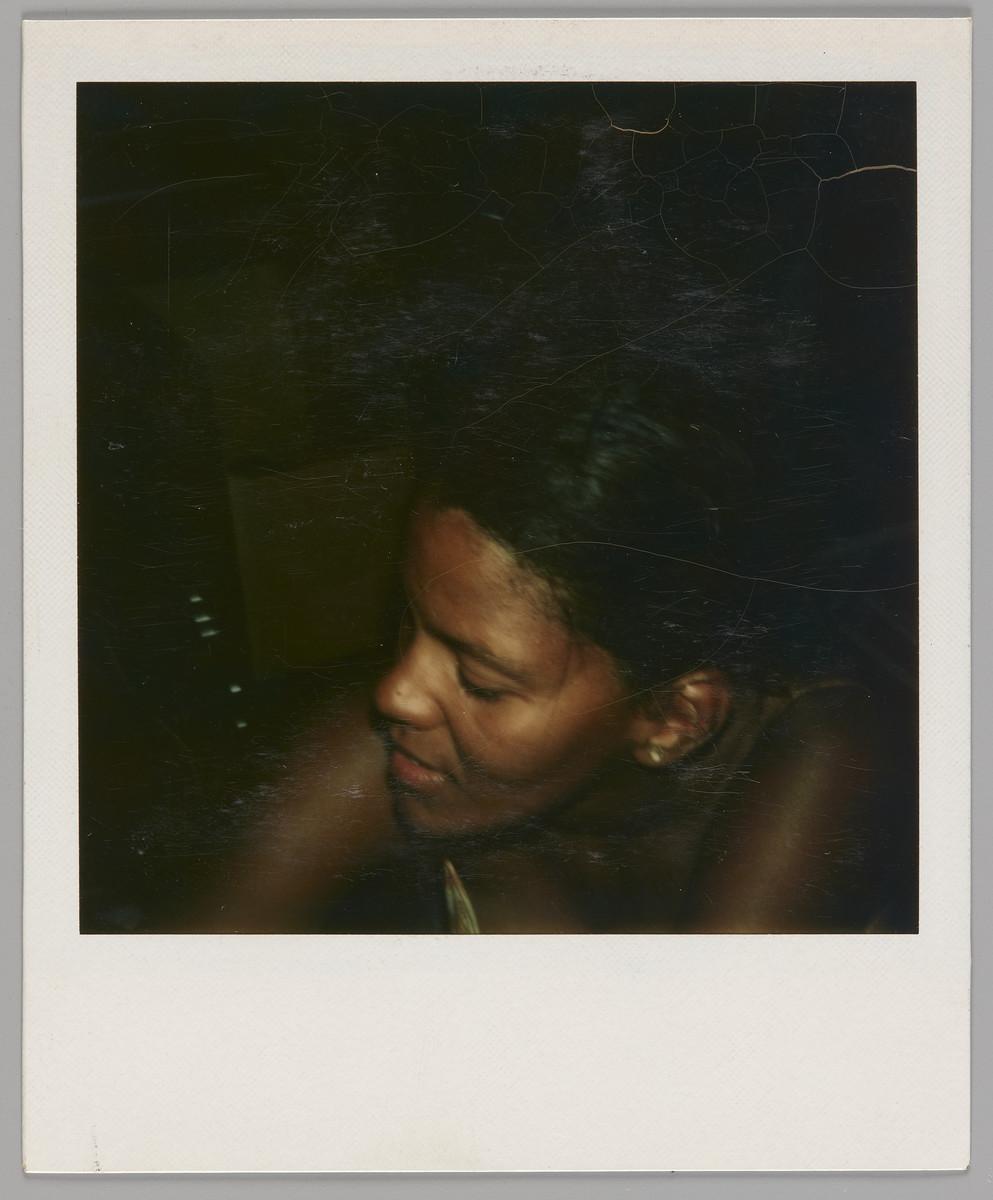

What Matters Most: Photographs of Black Life enshrines the role of the family photograph in shaping Black identities. Co-curated by artist Zun Lee and AGO Curator, Photography, Sophie Hackett, the exhibition of over 500 instant prints drawn from the AGO’s Fade Resistance Collection underscores the moments that matter most in the everyday – births, deaths, portraits, graduations and family gatherings among them.

We commissioned six graduates of Black Pen, a Toronto-based literary program for emerging Black-identifying writers, to compose personal responses to one or more of the photographs on view in a style of their choosing. The Black Pen alumni were first given a guided tour of the exhibition, which proved inspiring for each of them, and the results blew us away.

A moving contribution by African-American poet and essayist Dawn Lundy Martin to the What Matters Most catalogue inspired this commission. She writes about the implications of the Fade Resistance Collection being acquired and placed on view at a major art museum. She then turns her reflections inward, analyzing two of her family photographs and revealing the complex narratives they represent.

Take a moment to read this essay by Adeola Egbeyemi below.

On Resting in the Dark While Developing

By Adeola Egbeyemi

I don’t have family photos up on my fridge. I’ve formed a habit of suppressing my social media presence. Loved ones who bravely include me in pictures know this: sometimes I can’t let photographic moments just be photographic moments. I drag my feet. Mutter. Make silly faces.

I think I tend towards privacy. Even here: we writers were encouraged to pick one Polaroid and reflect on our Black lives. I thought mmm, no and wrote a 1,200-word essay on aesthetic sublimity. Thankfully, that take will remain unseen.

Still, I think this introverted tendency was heightened by experiencing over five hundred photographs of Black life.

I consider it sublime—as Kant writes: amazement bordering on terror. Horrifying. Sacredly thrilling. I couldn’t look at one photo for too long. I thought about Californian urban planning, graduation (the amazement), childhood Christmases, fashion trends in the ‘80s and in 2018, terracotta tile, the Möbius strip as a metaphor for pop culture development, 0.5 lens selfies, auntiehood, summertime, carpeted living rooms, funerals, graduation (the terror) and 50th birthdays. Is this overwhelming? Today—already never coming back; any conceived tomorrow—bound to be history. Is that a burden? Following your dreams, falling in love, road trips with friends, cherishing youth, forgiving family, good health. Is this an ad for Nikon? The sublime developed into juvenile existentialism; the Daniels were right: everythingness feels empty in the centre.

Some photographic terms are interesting to think about in the light of Black life: Capture, shot, hang. Before dismissing this as woo woo high school English analysis nonsense, consider that the Art Gallery of Ontario, an institution that sustains discrimination, racism and oppression, now owns these Polaroids, has possession of documents of Black families, funerals, graduations, parties—lives. I also thought about the superimposition of blackness on Polaroid photography, specifically. Early colour film photography was designed for white skin. The light range was so narrow that Black people would be rendered invisible. The light range only got expanded when Kodak’s biggest paying clients – the confectionery and furniture industries – complained that dark chocolate and brown furniture couldn’t get photographed. People with dark skin know: it takes serious effort to be visible in a Polaroid, let alone look loved by the camera. Polaroids were not made to capture us, but here we are, in despite. Here we are, also, collected en masse.

One runner-up photo choice I have rests in this needed balance of visibility and capture—a photo that, probably due to bad development, is completely black. Wouldn’t it be thoughtful to unpack a literal Black square? Another potential pick of mine was pretty meta. But here’s take two: I feel like taking a Polaroid really limits your behaviour. Film is expensive, so you take careful shots at times you think are important. Film has a chance it won’t develop well, so you take it in the best light possible. With that, it’s almost unthinkable that someone dared to take a Polaroid of a Black person for no obvious reason to us, with no distinct expression, in no discernable location, at no stated time. In fact, it's one photo out of a set of three of the same subject. That feels really bold to me. Graceful. And very cool.

I found a cool Polaroid once. A vintage 600 Flash. My housemates and I were taking the occasional night stroll to the convenience store. Westdale is the best neighbourhood, people just put cool stuff on the sidewalk for anybody. I was stoked. I held onto it for five months. I got help to pick up the right film from Staples and photographed a fun day where we drove to frozen waterfalls and a castle, but the pack was expensive, so I was cautious of each take. However, the first picture was a quick test. Make sure the camera works. From my bedroom, I took a Polaroid of the tree outside our dank student house, pillowed with white snow. Carefully captioned it in Sharpie. December 1, 2020. The tree was over two storeys tall, knotted like a knuckle bone, and home to loud squirrels that jumped from its top branches onto other soft trees that ran all the way down to the gothic window of the United Church harbouring the end of our oval-shaped street. An oak tree, I think. It was one of those trees you imagine tying an old tire to a low branch and just swinging. I lost the Polaroid photo. I gifted the camera. The tree was cut down nine months ago, and we all moved out one month later.

I don’t know if we deserve this world.

All you private people, I feel you.

Adeola Egbeyemi tells many stories that sometimes get written down. She loves playing with form and alternate narratives. Her creative work has been published in GRIOT (2022) by the Nia Center and Penguin.

Black Pen is a Toronto-based literary program for emerging Black-identifying writers, founded by Nia Centre for the Arts. The program’s first six graduates published GRIOT: Sojourn into the Dark in 2022, their first chapbook of fiction and non-fiction. Read the writings of Yvvana Yeboah Duku, Adeola Egbeyemi, Onyka Gairey, Saherla Osman, Kais Padamshi and Omi Blue, all on Foyer.

![Unknown photographer, Chillin on the beach, Santa Monica [Couple on beach blanket]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-04/RSZ%20WMM.jpg?itok=nUdDiiKr)