Alexander Arslanyan talks preserving Polaroids

The photography researcher explains what to look for after you shake your Polaroid picture.

![Unknown photographer, Chillin on the beach, Santa Monica [Couple on beach blanket]](/sites/default/files/styles/max_1300x1300/public/2023-04/RSZ%20WMM.jpg?itok=mtDNSb7g)

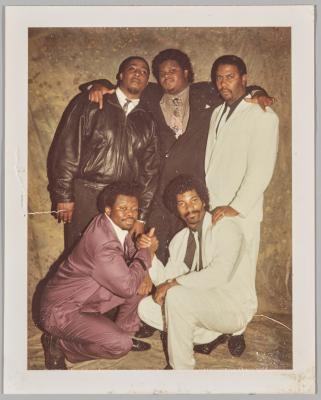

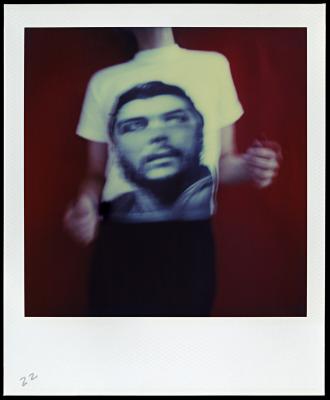

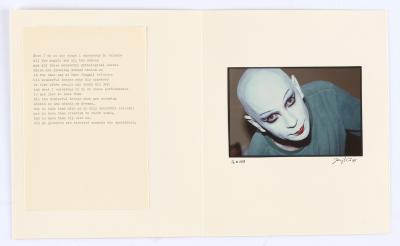

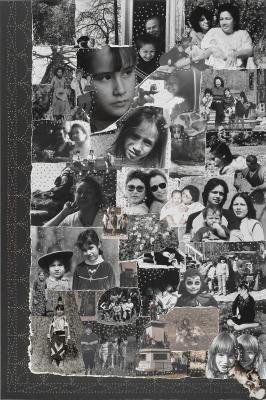

Unknown photographer, Chillin on the beach, Santa Monica [Couple on beach blanket], April 17, 2005. Colour instant print (Polaroid Type 600), 10.8 x 8.8 cm. Fade Resistance Collection. Purchase, with funds donated by Martha LA McCain, 2018. © Art Gallery of Ontario 2018/771.

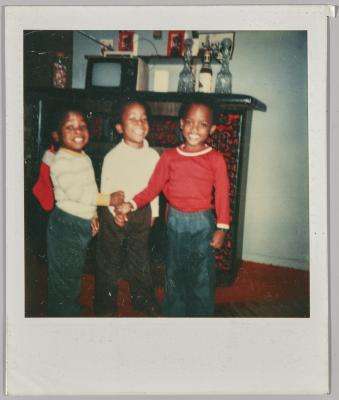

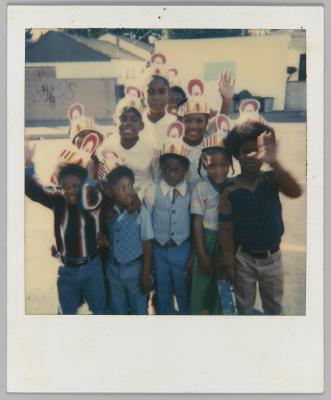

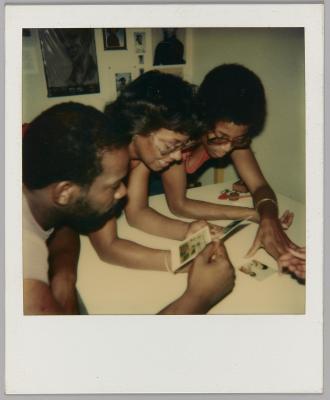

Exhibitions are born, and come into this world, with many helping hands. Co-curated by visual artist Zun Lee and Sophie Hackett, AGO Curator, Photography, preparations for What Matters Most: Photographs of Black Life [closed January 2023] involved significant research and discussion, as the found images in the exhibition came to the museum with little or no documentation. This is the first exhibition to showcase works from the recently acquired Fade Resistance Collection, which features more than 3,000 Polaroid instant prints.

To aid in the research, the curatorial team welcomed Alexander Arslanyan, then a grad student in Film + Photography Preservation and Collections Management at Toronto Metropolitan University. Interested in the preservation of Polaroid-brand instant photos, his assignment was to help curators and conservators identify the types of Polaroid formats used, record and decode the manufacturing codes on the backs of the Polaroids and determine the dates.

We caught up with him to hear more about what he learned about caring for and identifying Polaroids.

Foyer: What did you come to the AGO hoping to learn about Polaroids?

Arslanyan: I was very keen to see and understand how Polaroids degrade over time, and the challenge up until coming to the AGO was getting access to a large enough collection of Polaroids to make an accurate sample for analysis. One of the hard things about 20th century film and photographic products is that the manufacturers (for obvious reasons) didn’t publish a lot of research about their own products, so anyone looking is reliant on secondary sources.

Foyer: Remind us, when were Polaroids invented?

Arslanyan: Polaroids were invented in 1948. And they were hugely popular from the very beginning. On the first day they were released, the Polaroid Corporation brought 56 cameras to a Jordan Marsh department store in Boston, hoping they’d sell out by Christmas. They sold out that same day. By the end of 1958, they had sold 900,000 cameras.

Foyer: Were Polaroids a worldwide phenomenon?

Arslanyan: Yes. And many others got into it - Fuji and Kodak also produced instant prints. There’s a good story about how the Soviet Union tried to mass produce instant film for its markets, by illicitly importing Polaroid products and trying to reverse engineer them. To little success.

Foyer: What were you hoping to learn by looking at the Fade Resistance Collection?

Arslanyan: I wanted to see how Polaroids degrade over time and naturally − outside of a museum vault. Which was why working with the Fade Resistance Collection was so ideal - because there were thousands of images, that up until their entry into the AGO Collection, had not been kept in perfect conditions − no humidity controls, no acid free paper or dark boxes.

The range of the Fade Resistance Collection provides a remarkable cross-section of instant film technology. Polaroid film has evolved a lot, as have other formats − close to 50 or 60 instant film formats have been developed since the 1940s. The first film manufactured was a peel-apart orthochromatic film, which means that it wasn't sensitive to red light. It wasn't a true black-and-white, but sepia in tone. And then from 1948 until 1962, the focus was on creating instant colour film. And then from 1963 to 1972, there's another period of innovation where they're continuously trying to create Sx70 integral film, the first non-peel-apart instant print.

Foyer: Left in nature, what are the actual stages of degradation of a Polaroid photo?

Arslanyan: It’s well known that Polaroids are less stable than other photographic products, and I was very surprised to see just how well the images in the Fade Resistance Collection have stood up. There was considerable dye staining in some, some yellowing and peeling in others − all of which are natural impacts of time, humidity and light. Polaroids have no fixative bath, so over time and in bad conditions, the dye will transfer to the surface, and blur and stain the image, ultimately leaving you with a muddy and faded image. The warmer, the brighter the storage conditions, the faster the degradation. Polaroids are complex reactions, involving more than 1,600 layers of chemicals. But the polyester coating on these images is ideal − it’s non-reactive, so they have the potential to last. That’s the beauty of the design.

Depending on when the film was made, you also see colours fading at different rates. Up until 1972, the colour film used the same types of dyes, which means the colours in them faded at relatively the same rates. After 1972, they used different types of dyes in the same image, meaning you get greater colour shifts, happening at different times. Which is why, in my opinion, the older Polaroids look better than the newer ones. Because they've faded at a consistent rate.

Because no one is making Polaroid film anymore − the instant film offered by the company now called Polaroid is significantly different − the need to better understand how to preserve these materials for the future is essential.

Foyer: Clearly, when you’re cataloging thousands of Polaroids and others instant prints, there’s a lot to consider. Did Polaroid have a simpler way to identify its own various products?

Arslanyan: It’s fascinating. Polaroid was very consistent and tracked every piece of film ever produced, by stamping them with an individual serial code. That code will tell you the month and year it was made, and the machine it was made on. But there’s a nuance to it − the codes are guided by an internal logic. For instance, the number 0 in this case representing the year may signify either 1950,1960 or 1970. So you have to then start looking at the type of film that it was, and know when that type of film was in production. The location of the serial code is also significant − again these were done manually, so there is the potential for human error. In 1982 Polaroid actually published a two-page guide to how to read these serial numbers, but much is missing.

The beauty of this serial code system, in examining the Fade Resistance Collection, means that by a stint of hard cataloging you sometimes are able to find matches − images made from the same batch of film that was produced in the same month and same year and in all likelihood owned by the same people. Which, when you consider that Zun Lee collected these images from all over − from different vendors, in different cities − is remarkable odds. Like finding a needle in a 3,000-piece haystack. But once you have the codes and it's in a database, you can do just that. In the exhibition What Matters Most, there is an installation of four or five photos of two young girls in front of a Cadillac in New York City. Until we compared the numbers, we had no idea these images were related, as they arrived separately.

Foyer: What’s the next step for your research?

Arslanyan: Next step in this research, ideally, would be to look at the Polaroid corporate archive, at Harvard University. They have it all, but none of it’s been digitized. When the original Polaroid company collapsed, they just gave them boxes and boxes of materials. The current company doesn't own any of the original patents, and it will be interesting to see what potential innovations can be unlocked. But getting access to that, even just to take a look at preservation recommendations, and internal memos related to it, would be huge for the field.

![Unknown photographer, Chillin on the beach, Santa Monica [Couple on beach blanket]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-04/RSZ%20WMM.jpg?itok=nUdDiiKr)