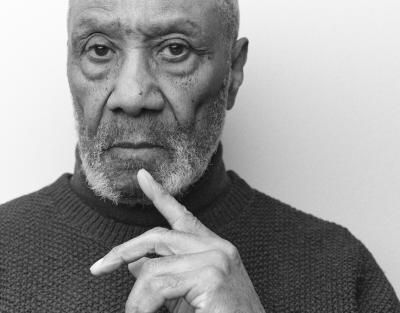

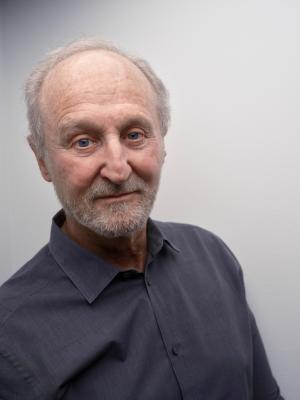

Mining the Archive With Stan Douglas

The acclaimed Vancouver-based artist reflects on his fascination with history and works on view

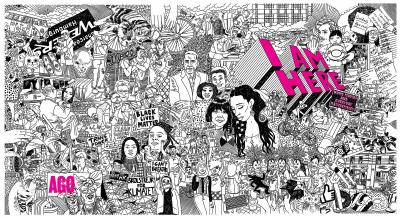

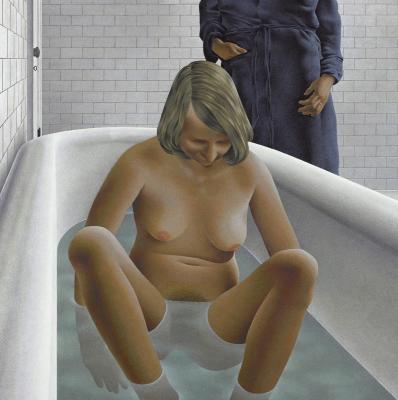

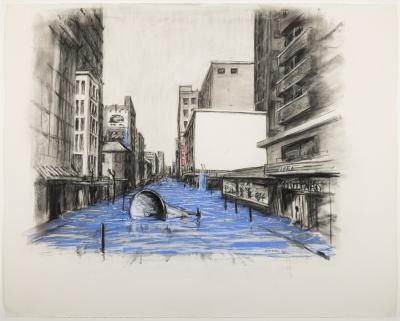

Stan Douglas, Abbott & Cordova, 7 August 1971, 2008. Chromogenic print, 177.8 × 290.8 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario, Gift of the Estate of Philip B. Lind, 2024. 2024/41. © Stan Douglas. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner

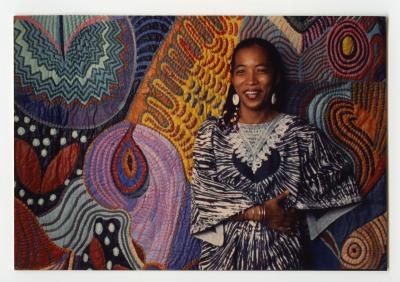

For Stan Douglas, pivotal moments in history are an opportunity to better understand the present. Over the last three decades, the Vancouver native has used his distinct command of photography, film and installation to unpack and reinterpret historical archives. Three works by Douglas demonstrating the range of his oeuvre are currently on view at the AGO – two in the exhibition Light Years: The Phil Lind Gift and one in the exhibition The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

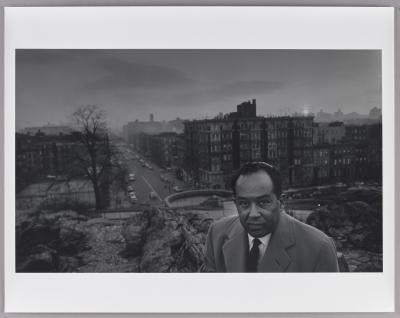

Douglas’s relationship with the neighbourhood depicted in Abbott & Cordova, August 7, 1971 (2008) dates back to his time in art school in the 1980s. The grand photograph, on view in Light Years, features a chaotic scene from the Gastown riots of 1971 in Vancouver’s Downtown East Side. After attending art school and situating his studio in the area for years, Douglas staged a full-scale re-enactment of the 1971 event with over 100 actors in 2008, resulting in a composite photographic work of remembrance.

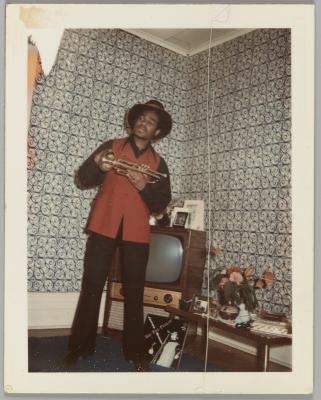

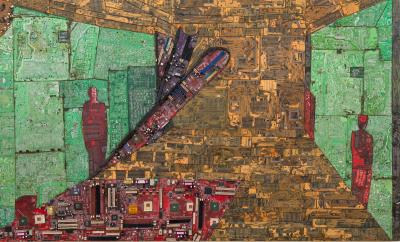

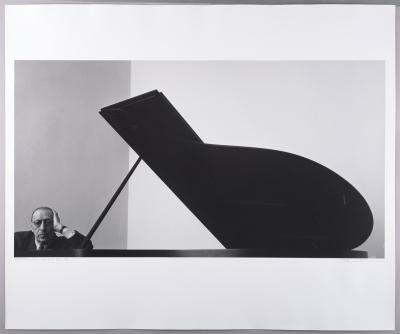

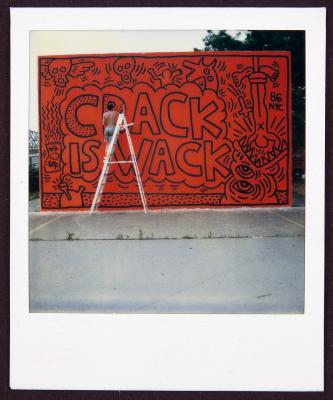

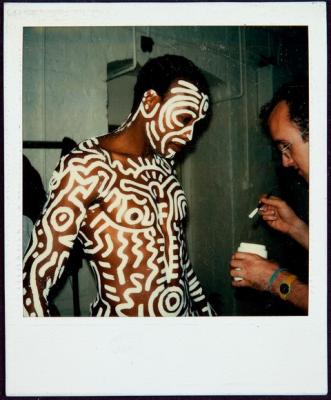

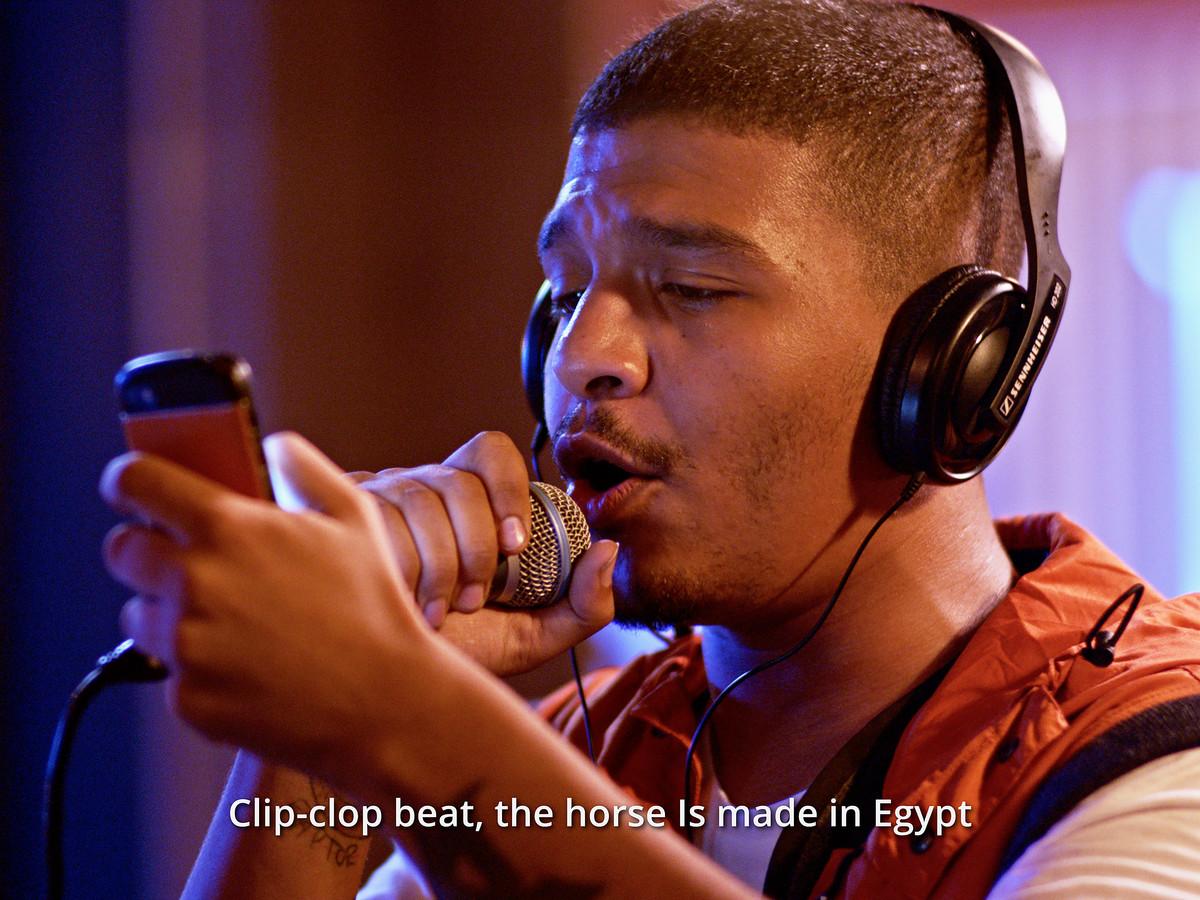

Part of his solo presentation at the 2022 Venice Biennale of Art, Douglas’s two-channel video installation ISDN uses rap as a means of intercontinental dialogue between sites of protest. Inspired by the Arab Spring and London riots of 2011, ISDN features UK grime and Egyptian mahraganat rappers in their respective studios, trading verses back and forth over the telephone using ISDN technology. Currently on view at the AGO as part of The Culture, the immersive installation invites visitors to consider hip hop’s revolutionary power.

Before his upcoming talk at the AGO, Douglas spoke to Foyer about his fascination with history, Vancouver’s Downtown East Side, and the global impact of hip hop.

Foyer: Much of your work bridges the gap between the historical and the contemporary. Can you talk about why history is so important to you and why you continue to mine historical archives as the starting point for many of your works?

Douglas: I think the question is when does history start and when does it stop? A lot of things that are thought to be historical are ongoing. Their effects are ongoing. I try to find pivotal moments which are perhaps forgotten, or maybe lesser known or understood, and find out how they can still have an impact or a relationship to our lives today. Sometimes it’s a case of things which did not happen, but had a possibility of happening, and we didn't take that road. Perhaps it's a road we should have taken, and looking at that parallax between these two points of view is my interest.

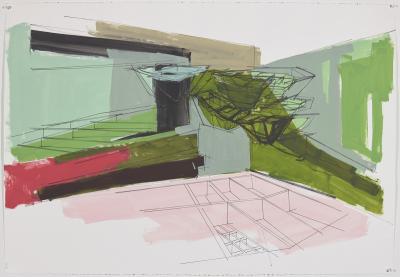

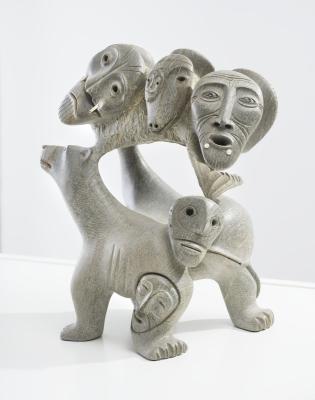

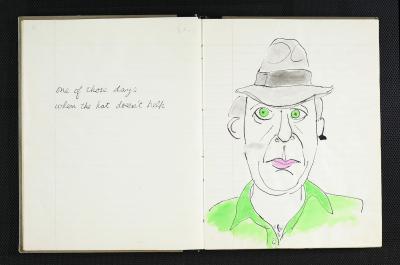

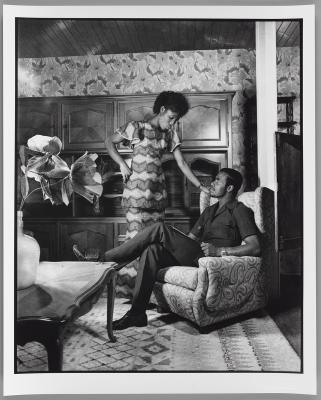

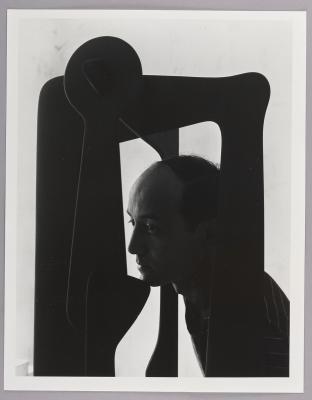

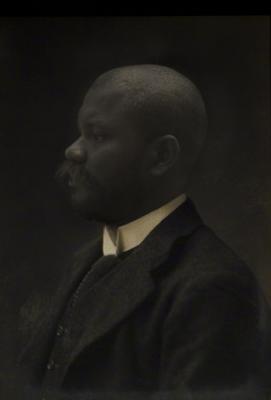

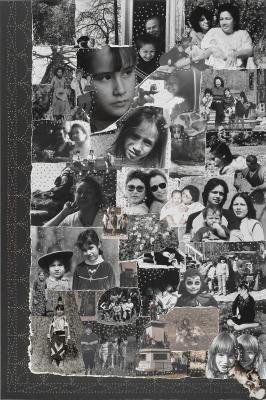

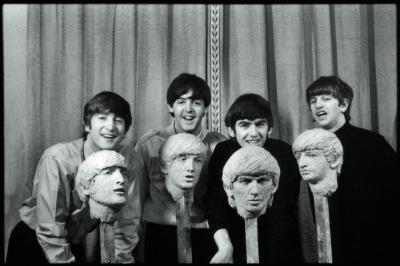

Image courtesy of Stan Douglas

Your photograph Abbott & Cordova, August 7, 1971, is currently on view at the AGO. Can you share some of the inception story of the work with us? What originally sparked your interest in Vancouver's Gastown riots?

That neighborhood has been a part of my adult life ever since I went to art school in the 1980s. I went to the Vancouver School of Art when it was in Gastown, so I got see the Downtown East Side in a very intimate way. The Woodward's Building, then the Woodwards’ Department Store, which is where Abbott & Cordova, August 7, 1971 is installed, was my art supply shop in a sense. I would find materials or information there that I used to make things. The neighbourhood was home to my first studios, and the studio I’m in right now is a few blocks east of Woodward’s. I've always been in this neighbourhood, in a way, watching it decline over the years.

When the city of Vancouver was hosting Expo 86 [The World Exposition on Transportation and Communication] and decided to clear out the whole area to make room for people who would be visiting, displacing the mostly older working-class men who had worked in the resource industry and were living in single room occupancy hotels. Around the same time the provincial government stopped funding halfway houses, and as a result, many people struggling with mental health and addiction related issues were without housing and began populating the streets in the area once the fair was over. The neighborhood has always been a place where the city would almost allow certain illegal activities to take place, as long as it wasn’t spreading elsewhere. It was like that in the 1970s, and the event depicted in my work is a key moment in that history.

Around 1971, hippies had been moving into Gastown, squatting in a lot of the industrial buildings throughout the neighborhood. They were spending time in the local bars mixing with the old-timers and regulars, which the police didn’t like - they’d rather keep the communities quarantined. The police then began harassing young people in the bars. In response to the police aggression, the hippies organized a festival with hundreds of attendees. They had music , free watermelon and flowers for everyone, and a 10-foot-long joint - flaunting it all in the face of the cops. By 10 o'clock the chief of police had had enough, and brought in the riot squad. It all got out of control very quickly, because neither the Vancouver riot police nor the hippies were used to this kind of event - it left everyone scrambling for answers. This one zone,at the corner of Abbot and Cordova where the photograph is now installed, is the place where pressure was being released - where people were attempting to escape the cops who stormed in to apprehend them. That's the scene you're seeing in the photograph. It’s meant to be a token of that moment, without much explanation. It's not specifically saying “cops are good, hippies are bad” or “hippies are good, cops are bad.” It's basically there, installed in that location, so you can observe, wonder what happened to this place, and start a conversation.

What does your process look like when creating a composite photograph with so many actors and moving parts?

I had been working with film crews for a while, making my motion picture work and used the same crew that had worked in my last couple of videos and films to make this piece. We wanted to take a photograph composed of multiple scenes in one location. First, we explored doing the whole thing on location, but there were too many complications. The Canucks were in the Stanley Cup playoffs that year and the city would have to shut the streets down at a certain point for crowds to come out. Then the owner of the building on the corner across the Woodward's building wanted to charge us $50,000 to dress their window. We realized, for that amount of money we might as well just build a set. We found an empty parking lot, laid black top pavement, poured curbs, got hardware from the civic works yard (garbage cans, lamp standards), and we had a foundry cast metal street signs. We made some vintage garbage, newspapers from the day, posters from the day. We shot over three nights - two nights with the horses and actors in the foreground and background, and a final night for all the different layers of the images. Then, it was all stitched together as a composite in Photoshop.

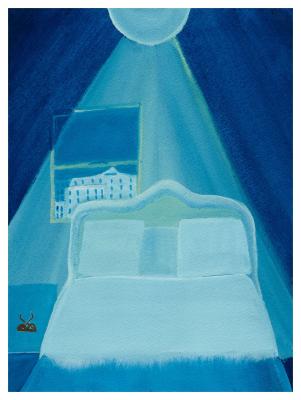

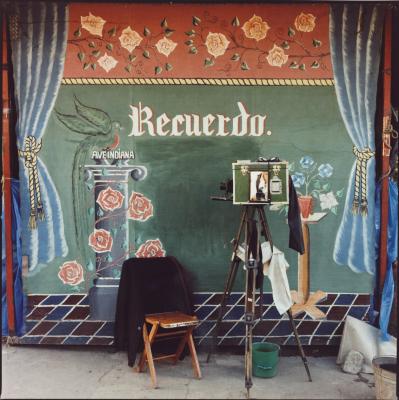

Stan Douglas, Film still from ISDN, 2022. Two-channel video projection, 1523 days 17 hours 52 minutes. © Stan Douglas. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner.

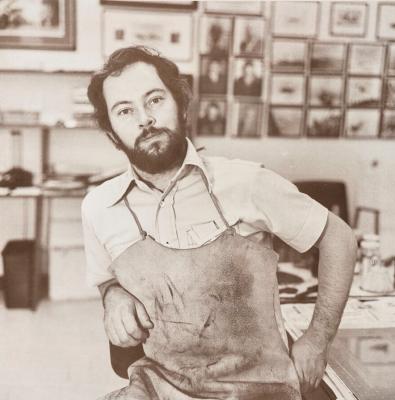

ISDN features rappers from both London and Cairo trading versus back and forth, seemingly across continents. Can you talk about how this work came about? Specifically, your choice to include rap as a cross-cultural exchange, as well as your choice to use ISDN technology as the conceptual framework of the film.

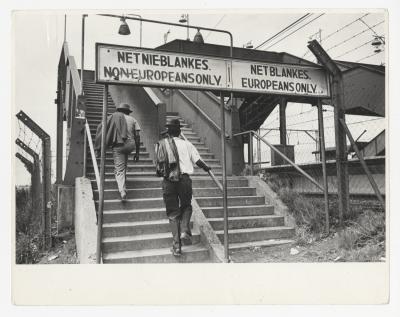

I was interested in the various uprisings that happened in 2011 and had imagining a parallel between them and the European revolutions of 1848. Basically, through ideas that were circulated in print media, all the nation states in Europe, aside from Britain and Russia who had very severe state police apparatuses, had cascading bourgeois revolutions demanding more representation for their taxes . They were all failures, but somehow the reforms they demanded became a model for what came to pass in the 20th century. I was curious about these events as failed revolutions that nevertheless set the spark for the possibility of change later on.

Although nation states paid attention to protesters in 1848, in 2011 people were protesting intuitively or in an explicitly political way the austerity after the 2008 stock market crash, and they weren’t being heard. By 2011, bankers were getting their bonuses again, but austerity was still in place. A lot of people couldn’t articulate it politically, but they still felt something was wrong, so they went to the streets in different ways to protest that. The Arab Spring was called the Arab Spring in reference to the Springtime of Nations, which was a nickname for the 1848 bourgeois revolutions.

I was reading a book about the 2011 uprisings and the author was saying that grime music in the UK was literally the soundtrack for what was going on in the streets, and protestors were playing it on their portable radios. As I looked into the music more, I realized they had taken the hip hop formula of rap plus electronic beats and applied that to a local idiom, grime, to make something new. I thought, if this happened in the UK, given the prevalence and the popularity of hip hop around the world, it must have happened somewhere in North Africa as well. I looked into the music scenes from that period in various places - Tunisia, Palestine and others - finding different variants of hip hop in local languages, but musically they were very often a carbon copy of some US model. In Egypt, however, there was a combination between a local genre called shaabi (a working-class party music) and hip hop called mahraganat. I figured this would be an ideal pairing with grime. I set up the premise that through this obsolete audio technology, ISDN, people are communicating across the world, rapping over beats at another location.

Years ago, I was introduced to ISDN technology when I used it for audio dubbing. I chose to use it in the context of this work because it is a very stable and reliable system - I think CBC still uses ISDN. I know musicians tend to love vintage equipment that works well, so I worked with the premise that these people may be making a musical and lyrical connection over ISDN.

Stan Douglas, Film still from ISDN, 2022. Two-channel video projection, 1523 days 17 hours 52 minutes. © Stan Douglas. Courtesy the artist, Victoria Miro, and David Zwirner.

Douglas will be live at the AGO on Wednesday February 12 at 7 pm. Book your tickets here. His works Abbott & Cordova, August 7, 1971 and MacLeod’s Books, Vancouver are on view now as part of Light Years: The Phil Lind Gift. His video installation ISDN is on view now as part of The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary art in the 21st Century.