Growing up with Keith Haring

The youngest sister of Keith, Kristen Haring, recounts some of her favourite memories of her brother

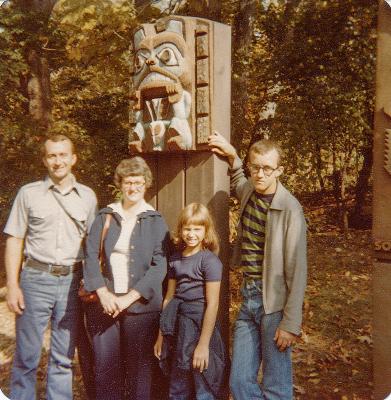

Members of the Haring family at the zoo in 1979. From left to right: Allen, Joan, Kristen, and Keith. Photograph taken by Karen DeLong

Before he was an artist, activist, and international icon, one of Keith Haring’s first and most important titles was big brother.

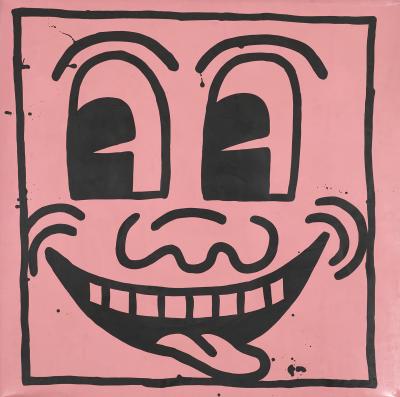

On view now at the AGO until March 17, the exhibition Keith Haring: Art Is for Everybody provides a major overview of the late artist’s career. Growing up in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, Keith was the eldest brother to sisters Karen, Kay, and Kristen. Keith left his hometown to study commercial art in Pittsburgh, eventually moving to New York in 1978 to attend the School of Visual Arts (SVA). In New York, Keith’s career began to take off, starting with the graffiti he famously created in subway stations. Keith developed an impactful career, working with various mediums and befriending and collaborating with various artists and celebrities, including dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones.

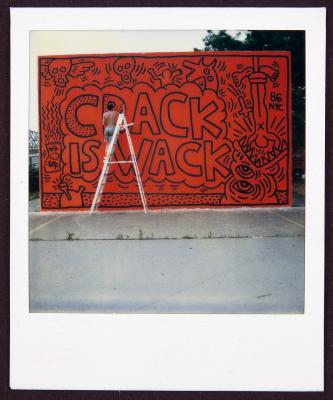

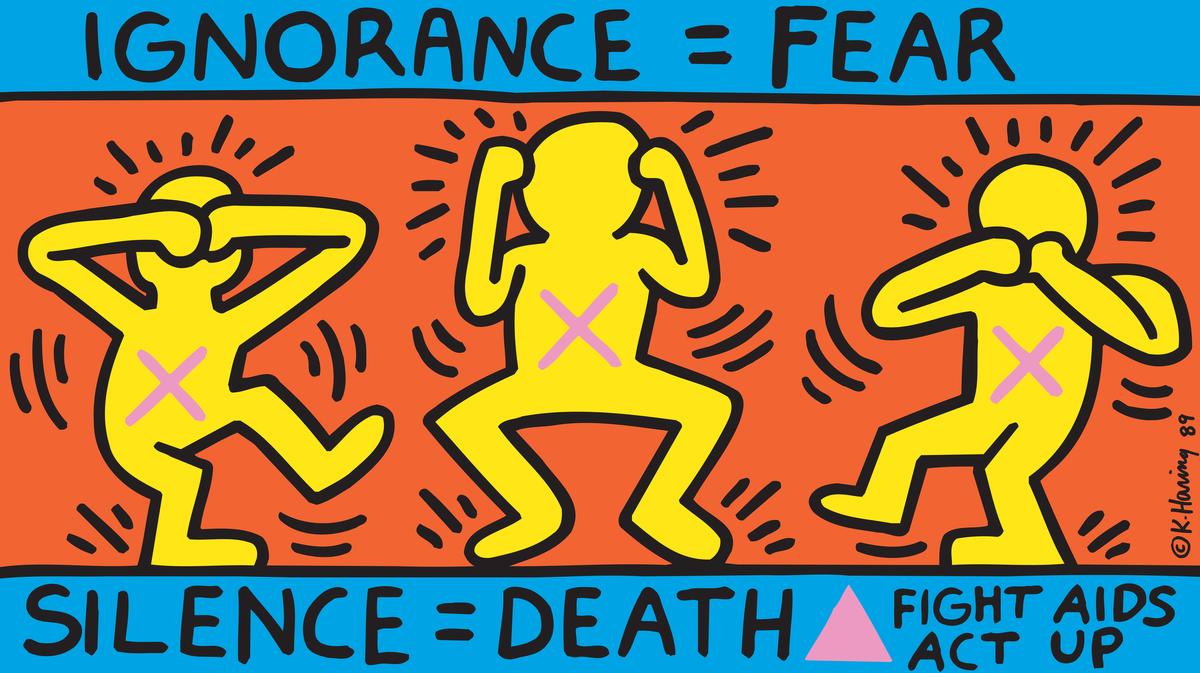

As his work gained recognition, Keith remained steadfast in keeping his art accessible and relevant to the public. Building off his subway graffiti, he created public murals around the world and opened the Pop Shop in 1986. Activism also remained core to Keith’s work, challenging capitalism and white supremacy and using his art to raise awareness around the AIDS epidemic.

Keith Haring, Ignorance=Fear, Silence=Death, 1989. ACT UP poster, 61 × 109.2 cm. The Keith Haring Foundation © Keith Haring Foundation

Keith was diagnosed with AIDS in 1988, and before his death in 1990, he established the Keith Haring Foundation to support AIDS service organizations and organizations assisting underprivileged children. Continuing Keith’s mission to this day, the Foundation is currently led by Keith’s close friend Gil Vazquez and has created $50 million worth of grants to date.

One of the best people to recount Keith’s artistic journey from start to finish is Kristen Haring, Keith’s youngest sister. From creating art together as children to attending his first exhibitions and becoming a founding member of Keith’s foundation at only 19, Kristen followed her brother through it all. Despite a 12-year age gap, the two were close, remaining in contact through letter writing and frequent visits to New York City by Kristen as she grew older.

Establishing her career as a historian of science and technology, Kristen remains connected to the art world as part of the Keith Haring Foundation and continues to visit exhibitions dedicated to Keith’s work. Most recently, Kristen attended the opening of Keith Haring: Art is for Everybody at the AGO, returning for the first time since 1997 when she attended the AGO’s first exhibition dedicated to Keith's work with her parents.

Kristen Haring (right) with Georgiana Uhlyarik, the AGO's Fredrik S. Eaton Curator, Canadian Art. Image courtesy of Georgiana.

As Keith Haring: Art is for Everybody wraps up at the AGO, Foyer spoke with Kristen about her childhood with Keith, her fondest memories of her brother, and how it felt to return to the AGO after 26 years.

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Foyer: Can you share some of your favourite childhood memories of your older brother?

Kristen: Probably the reason that we formed a close relationship despite our age difference is that Keith made an effort to engage me in the things he was doing and experiencing.

One time when I was five years old, Keith was working with watercolours, pen and ink at his desk. I was pestering him to play with me and stuck my hand in front of his paper to demand attention. Keith grabbed my hand, covered the inside with paint, and pressed it onto the paper. Then, he had a flash of inspiration, hurried me off to wash up, and re-painted my hand. We did this a dozen times, making differently patterned and shaped handprints. Once they dried, Keith outlined the jagged watercolour edges with ink. He made one print into a drawing for our grandmother and the rest he made into a mobile for me.

A few years later, when he was living in Pittsburgh and then New York, Keith would write to me about jobs he had, where he was finding space and supplies to make art, and even what foods he was eating. The letters were rich glimpses into his day-to-day life. For a while, we played a game where he’d send me a list of words that I should incorporate into my next letter, and I’d also send him a list of words to use in a letter to me. At the time I thought it was simply a way to encourage correspondence, but later I realized that Keith had started this game when he had been reading about [writer and visual artist] William S. Burroughs’s cut-up methods and started making his own text collages.

The Haring children on Christmas, 1975. From left to right: Karen, Keith, Kristen, and Kay. Photograph taken by Joan Haring

Foyer: When Keith was first developing his career in New York, you were only in the sixth grade and would take periodic road trips to visit and attend his exhibition openings. At that time, how did you make sense of your brother’s art and the world he was a part of?

Kristen: My family and I went to Keith’s first solo exhibit in 1978, at the (then named) Arts and Crafts Center of Pittsburgh. The building was beautiful, the works were large — it was an impressive first show. The openings that we went to at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery in New York, starting in 1982, were next level, so packed with people that it was hard to see the art. In both atmospheres, though, from my perspective as Keith’s little sister, my attention was on the reception Keith was getting more than on the art itself. It was so wonderful to watch him achieve the goal he’d long had — to be a working and exhibited artist. Even in 1982, when his success was just beginning, it was a huge step for 24-year-old Keith. My appreciation of Keith’s art emerged as my immersion in his images allowed me to understand them and as I learned about art history.

Kristen beside one of Keith's works in 1977. Photograph taken by Allen Haring

Leaving my small-town, teenage life and dipping into Keith’s world, I always had culture shock. When I was old enough to spend time with Keith on my own in New York, he liked to share his routine with me, letting me experience his world for a day or two. Keith took me to the only place in SoHo where you could buy Orangina at the time, to a gallery show of Cindy Sherman’s photography, to pick up wholesale lilies in the Flower District, to visit friends, to the clubs he could get me into underage. It was exhausting to shadow him for a day, popping in and out of the subway and striding down the street. The only time I could catch my breath was when he was working in his studio, painting, or answering mail and calls. Keith was a ball of energy.

As he sold artwork, Keith gained freedom from the array of part-time jobs he had strung together for years and a cushion for indulgences. He thought it was funny — or, he would have said “hysterical” — to put me up in a fancy hotel or buy me clothes by Comme des Garçons and Yohji Yamamoto.

(To help visualize this time in Kristen's life, see this 1986 photograph of Kristen with Keith and Nina Clemente on his shoulders at an exhibition opening for Kenny Scharf)

Foyer: While many know about Keith’s legacy, you grew up with two artists in your family. Your father, Allen Haring, was an amateur cartoonist and taught Keith how to draw at a young age. Was cartooning and drawing also a large part of your childhood? Do you have fond memories of your father’s cartoons?

Kristen: Our father drew with all of his children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren to entertain us and to communicate. Whenever someone asked Allen to explain how something worked or how to get somewhere, he would make beautiful and precise drawings while he spoke. It was as natural to him as talking. Our father would also draw, paint and woodwork just for pleasure. Keith developed that fluency with and love of drawing. I would say my sisters and I developed a competency for drawing and didn’t shy away from art projects. My sister Kay painted a mural along her home’s staircase, my sister Karen had a hobby business painting silk scarves, and I undertook a textile project to explore a historical concept.

I’d have to say that all of my memories of our father drawing are fond because drawing brought such joy to him and whomever was watching. There’s only one exception: being his partner in the board game Pictionary was terrible! Instead of making a quick sketch to get me to say the word before the other team did, he drew intricate, perfect images. Our team would lose, but after the game, no one wanted to throw away Allen’s drawings.

A childhood photo of Kristen from the 1970s. Photo taken by Allen Haring

Foyer: You’ve developed your career around studying the history of science and technology and have published a book on the history of ham radio culture. Does your exposure to art influence how you approach thinking about science and technology? Growing up connected to the art scene through Keith, did you ever feel pressured to pursue a career in this field?

Kristen: I never felt pressured, neither by Keith nor by the rest of the family, to pursue a particular career path. Our parents encouraged our individual interests. I liked mathematics and studied it in graduate school. My alertness to the context and implications of science and technology (which I was lightly exposed to through Keith, and then formally in my liberal arts college program), plus the field's diversity of topics and methodologies, led me to science studies.

From my acquaintance with contemporary artists, I gained respect for artistic practice as a mode of investigation. This greatly influenced my teaching: I create hands-on projects that help students and fellow scholars research questions through physical engagement.

Foyer: The AGO showed their first exhibition dedicated to Keith’s work in 1997, which you attended with your parents. Returning to the AGO 26 years later to see Keith Haring: Art is for Everybody, did you have any new perspectives or insights on your brother’s work? How did it feel to return to the AGO to see your brother’s work again?

Kristen: Though Keith made art in response to specific elements of his environment, he wanted individuals to interact with the work, by bringing their own meanings to it. That openness means Keith’s art remains powerful, it rewards repeated looks, and it stands up to fresh interpretation.

Being at a different point in my life, I naturally have different anxieties and aspirations, which shape how I look at and understand the work. Our father died in July 2023, and during my return to the AGO for the opening in November [2023], my 1997 visit with my parents was much on my mind. At the most basic level, I was thinking about generational shifts and what art stands the test of time.

It was such an honor that the AGO would host another show of Keith’s work. I’m eager to hear how visitors who remember the 1997 exhibit react to this one. Plus, it’s exciting that a younger generation will see Keith’s art in the AGO for the first time.

Kristen Haring (fourth from the left) and her parents Allen and Joan Haring (second and third from the left) at the Member's Opening of Keith Haring Exhibition October 16, 1997. Photo by Christina Gapic.

Foyer: What is your favourite work by Keith and why?

Kristen: It might be a slight cheat because it contains thousands of images, but my favourite thing that Keith made is his chalk drawings in the New York subway system. The MTA (Metropolitan Transportation Authority) sold advertising space in the hallways and along the train platforms. When an ad expired, the MTA would cover it with black construction paper. We know from the photographs taken by his friend Tseng Kwong Chi that, in the first half of the 1980s, Keith made at least ten thousand chalk drawings on the paper covering expired ads. Chalk interacted with the soft-textured paper beautifully, producing a sharp white-on-black image. The drawings were delicate, prone to being smudged, and ephemeral, as soon as the MTA could sell the space again, the drawings would be pasted over with new ads.

I love the commitment exhibited by this long project: it averages roughly 40 drawings a week over five years. During that period, the subway drawings were a continuous presence in Keith’s life, a little like On Kawara’s Today series of date paintings. The project was a commitment Keith made both to drawing and to the community. Surely not everyone welcomed it, but he sincerely intended the drawings as an offering to subway riders, thinking any drawing was better to look at than a black rectangle. Keith felt the drawings put him in direct communication with a mass population.

Cultural phenomena grew around the drawings. So many people stopped and talked to Keith while he was drawing that he made buttons to hand out, first with his radiant baby and then other images. I’ve heard many stories from people who got into conversations with strangers because they were wearing the buttons. Other 1980s subway riders have told me about the air of mystery around the drawings. Keith didn’t sign the drawings, and people wondered who was making them and if they could all possibly be made by a single person. A dear friend of mine told me that in the early 1980s, she saw the chalk images in her dreams and puzzled over this with her therapist.

Keith only stopped the project when people started to steal and sell the drawings. He never wanted these works to enter the art market. They were intended purely as rapid communication from artist to audience, made in one moment and erased soon after.

See Keith Haring: Art Is for Everybody before it closes on March 17, located on Level 3 of the AGO. For entry to the Keith Haring: Art is for Everybody exhibition, purchase an AGO Membership or Annual Pass. Visit the AGO website for more details on how you can see the exhibition.

Keith Haring: Art Is for Everybody is organized by The Broad, Los Angeles and curated by Sarah Loyer, Curator and Exhibitions Manager, The Broad. The AGO's presentation is curated by Georgiana Uhlyarik, AGO's Fredrik S. Eaton Curator of Canadian Art.

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)