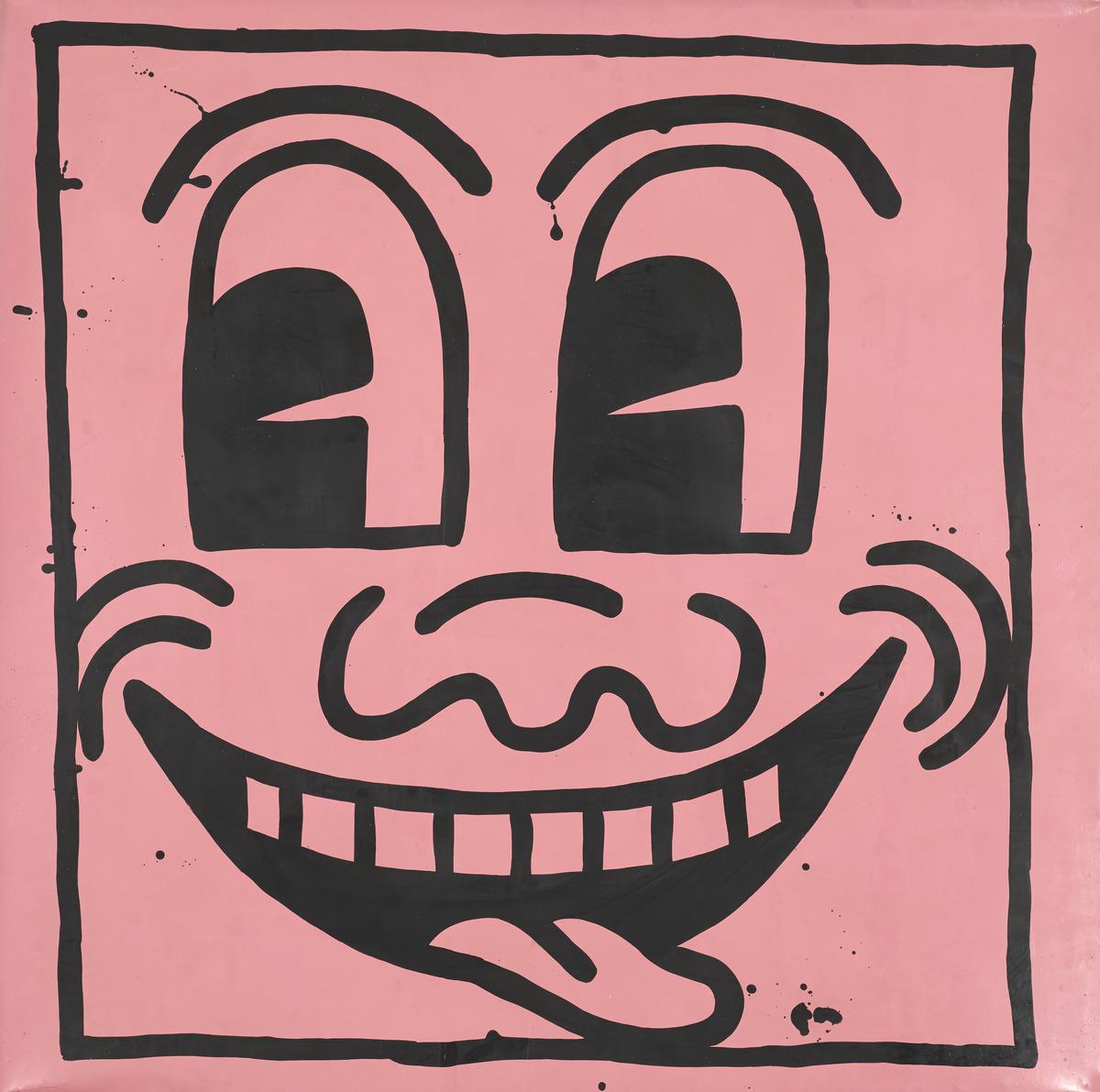

Seven ways Keith Haring made art

Wood, fiberglass, tarpaulin and video – here are seven mediums Haring incorporated in his work

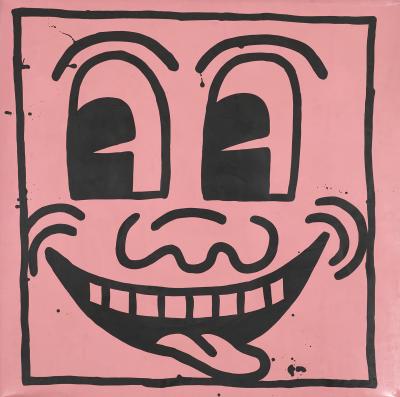

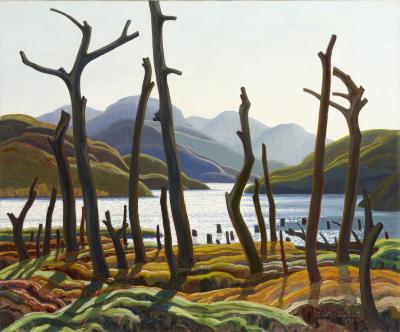

Keith Haring. Untitled, 1981. Ink on metal, 121.9 × 121.9 cm. Collection of Larry Warsh. © Keith Haring Foundation

Keith Haring’s artistic style is multifaceted and unmistakable with his vibrant use of colours, intricate line work, and signature figures such as the radiant baby and barking dog. Haring was also well-known for his wide-ranging activism, his works critiquing apartheid in South Africa, capitalism, white supremacy, and raising awareness for the AIDS crisis in the 1980s.

But what about the various mediums Haring used to share his art and activism with the world? Highlighting the range of the late artist’s career, Keith Haring: Art is for Everybody at the AGO showcases not only the diverse topics Haring tackled through his work but also the diversity in the mediums and scale he used. From tarpaulins to live performances and from event flyers to 3D sculptures, learn more about the different mediums Haring experimented with throughout his career and where they are on view in the AGO exhibition.

1. Tarpaulin and fiberglass

Keith Haring, Untitled, 1982. Baked enamel on metal, 109.2 × 109.2 cm. Courtesy of The Broad Art Foundation © Keith Haring Foundation. Photo: Douglas M. Parker Studio, Los Angeles

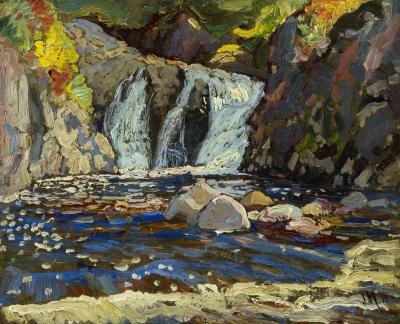

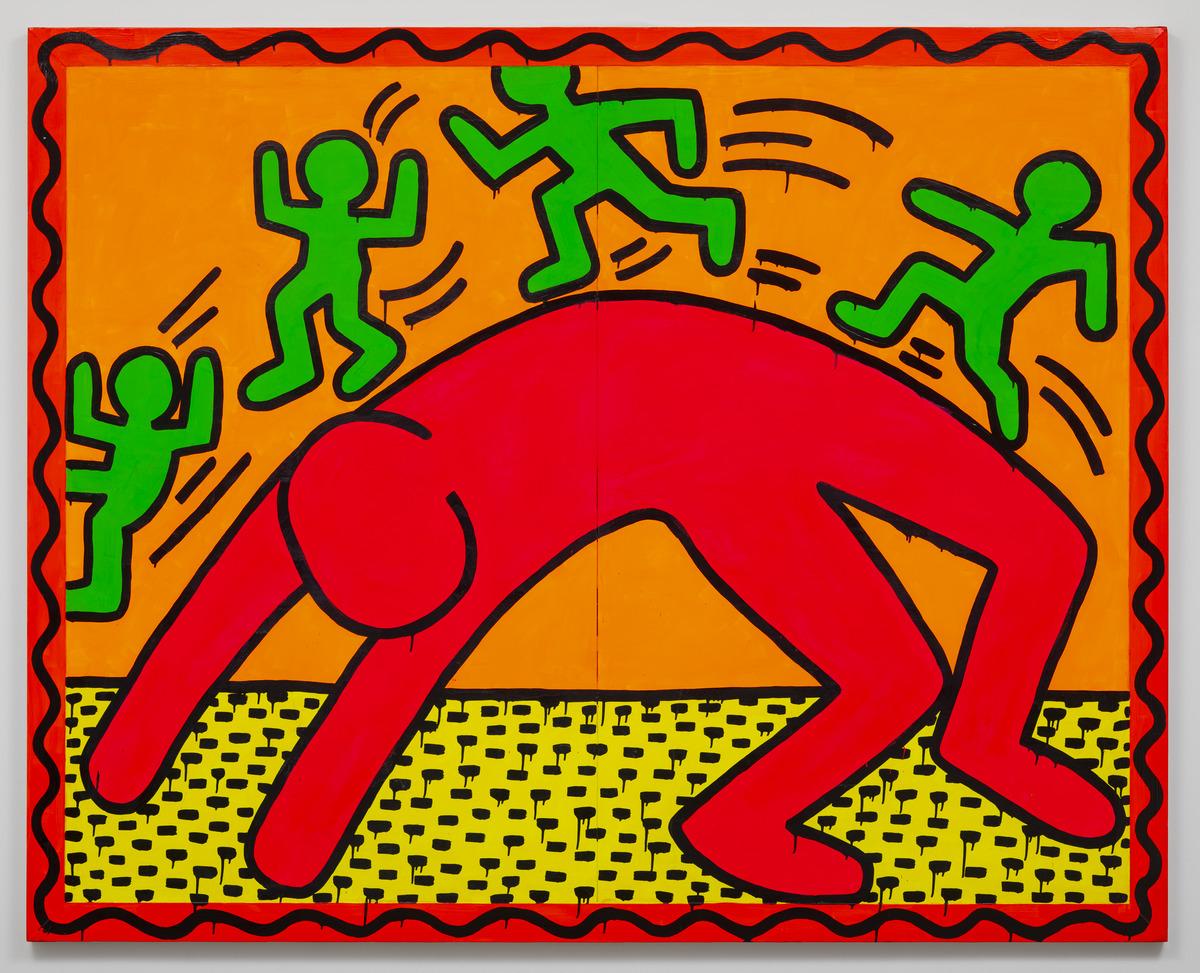

Those familiar with Haring’s paintings will know that the artist often went beyond the traditional canvas, painting on metal, wood, and even large tarps. In conversation with Foyer, Gil Vazquez, Executive Director of the Keith Haring Foundation, explained that Haring’s interest in tarpaulin represents his rebellious spirit and desire to push boundaries. According to Vazquez, the idea to start painting on tarps came to Haring after seeing the large tarps used to cover utility equipment at night. View Haring’s tarpaulin works in Rooms 1 and 2 of the exhibition.

On view in Room 1 is a set of fiberglass clay vases that Haring decorated with his signature line work, classic characters, and motifs of traditional vase painting. Haring saw his drawings on vases as “an ironic mixture of opposites,” meeting a history of vase painting with his contemporary approach of drawing with marker.

2. Day-Glo paint

Keith Haring, Untitled, 1982. Enamel and Dayglo on metal, 182.9 × 228.6 × 3.8 cm. Courtesy Gian Bochsler, Switzerland. © Keith Haring Foundation

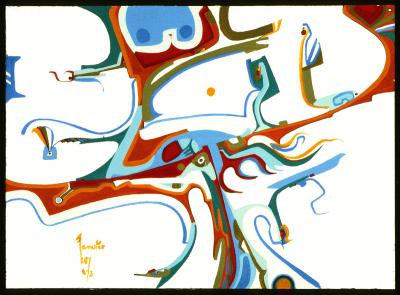

Be prepared to step into an 80s neon fever dream when you enter Room 4 of the exhibition. During his first major exhibition in 1982, Haring and his friend LA II (Angel Ortiz) transformed the basement of the Tony Shafrazi Gallery, showcasing art made with Day-Glo paint under ultraviolet light and painting the walls of the basement with pink and orange Day-Glo stripes.

Displaying works Haring created using Day-Glo, Room 4 of the exhibition replicates that very night, creating an immersive Day-Glo gallery painted with neon orange and pink stripes. Furthering this throwback is a background soundtrack of songs by the likes of Aretha Franklin, Grace Jones, and the Beastie Boys – all taken from Haring’s personal mixtapes.

3. Video

As you enter the exhibition, one of the first works that greets visitors is Trickfilmladen Animation (1984), a short animation Haring co-animated with Rolf Bächler and Franz von Reding for a Swiss store. Displayed on an 80s-era television, the animation features partygoing figures dancing to a funky beat, regularly interrupted by a barking dog.

A short walk from this animation leads viewers to a series of videos created by Haring. The artist was fascinated with semiotics, which is the study of signals and meaning-making. Inspired by the beat poet William S. Burroughs, Haring used video to experiment with language. In the video (F) Phonics (1980), Haring features his classmates from the School of Visual Art playing with the sounds of the digraphs (a pair of letters) featured behind them. Haring also plays with semiotics in Video Tape for Two Monitors (1980), where he breaks down language with a recording of himself playing on a TV behind him, each version of Haring taking turns to speak.

Haring also used video to capture his artistic process, such as in A Circle Play (1979) and Painting Myself into a Corner (1979), both on view in Room 3 of the exhibition.

4. Ephemera – posters, invites, album art

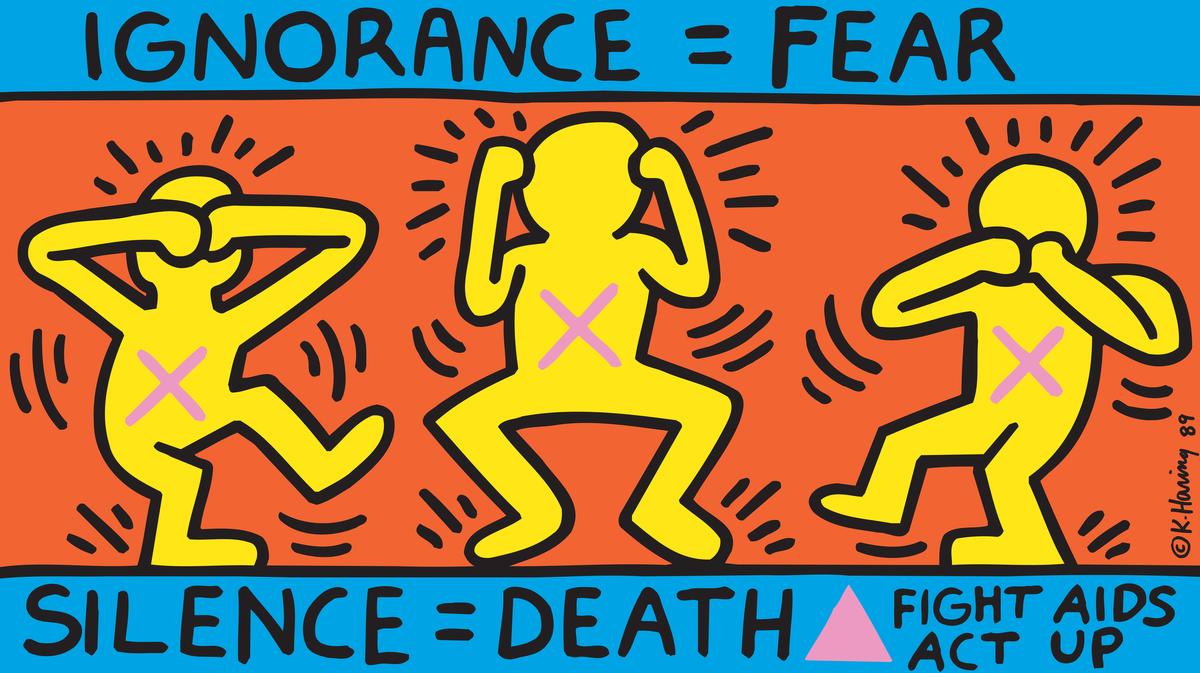

Keith Haring, Ignorance=Fear, Silence=Death, 1989. ACT UP poster, 61 × 109.2 cm. The Keith Haring Foundation © Keith Haring Foundation

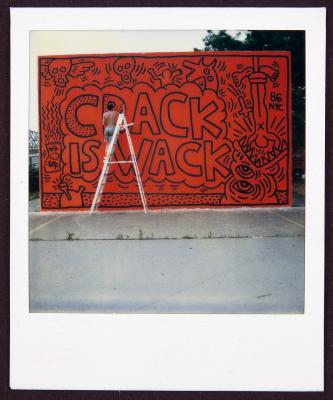

Activism is at the core of Haring’s art, and he took his activism to the streets by creating posters to raise awareness on several social and political issues. Haring designed over 100 posters, often handing them out at events, such as his Anti-Nuclear Rally Poster (1982), on view in Room 7 of the exhibition, which he handed out during a protest at the United Nations Second Special Session on Disarmament. Haring’s strong commitment to activism through both his works and actions continues to hold relevancy to this day for many.

Also on view is Haring’s Free South Africa (1985) poster critiquing apartheid in South Africa, on view on the title wall of the exhibition, and posters Haring created with AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) to raise awareness around the AIDS crisis.

Beyond posters, Haring was commissioned to create flyers, event invites, buttons and even condom cases and wrappers for various organizations and benefits, including Auction to Benefit UNICEF! [Phyllis Kind Gallery] (1986), Rain Dance: A Benefit for the Africa Emergency Relief Fund (1985), ACT UP FOR LIFE!! Benefit Dance Part for Act Up (1989), and much more. Also featured are various flyers for nightlife events and parties, including Haring’s annual “Party of Life” birthday celebrations, which were a key aspect of the artist’s time in New York. Some of the artist’s smallest works and ephemera are located in a clear case right outside Room 6.

Located just above this case of ephemera is drawing work Haring later used in the design of the record sleeve for David Bowie’s 1983 single “Without You.” Haring created cover art and record sleeves for a range of musicians including Sylvester, Doug. E Fresh, and Emanon. Music was a large part of Haring’s life and artistic process, from the friendships he developed with various DJs and his romantic relationship with DJ Juan Dubose, to the countless mixtapes he created and carried around with him. Haring often had music playing while working in his studio and at the openings of his exhibitions.

5. Wood

Haring created many large-scale sculptures during his career. On view in the exhibition are two large wooden sculptures which take their inspiration from carved wooden totem poles created by Indigenous groups from the Northwest Coast of Canada and the United States. Haring rejected racism in all its forms and actively campaigned against it. Yet his use of Indigenous, African, and ancient communities' cultural expressions to develop his own visual language and imagery did not acknowledge Haring's own privileged position.

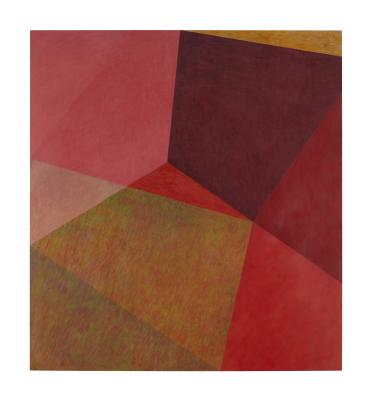

To create Robot (1983) and Untitled (1983), Haring deployed the carpentry knowledge of his friend Kermit Oswald, learning how to use power tools to carve the wooden panels which he then painted with Day-Glo paint. These sculptures aim to critique capitalism, consumerism, mass media, nuclear power and unprecedented technological advancements – see them in the “Monumental” room (Room 7) of the exhibition, which is dedicated to large-scale works Haring created to address pervasive issues including abuse of power.

6. Fashion

Keith Haring, Keith Haring and Madonna, "Speed the Plow" Production, November 28, 1989. polaroid - facsimile © Keith Haring Foundation

For some, their first encounter with Haring’s work is through clothing. Over the years, countless brand collaborations have incorporated Haring’s colourful linework onto t-shirts, bags, shoes, and even jewellery. A big believer in keeping his art accessible, Haring even designed and sold his own merchandise such as t-shirts and buttons through his Pop Shop.

However, Haring’s brush with fashion didn’t start with creating his merchandise. During his time in New York, Haring developed many famous friendships, leading him to design fashion pieces for performances.

In Room 6 of the exhibition you can see the pink leather suit, 3-Piece Leather Suit (1983), that Haring and LA II designed for singer Madonna and Snake Totem (1984), a headpiece Haring created with jewellery designer David Spada for model and singer-songwriter Grace Jones. Madonna even wore the suit Haring created for her at his 1984 “Party of Life” birthday celebration, where she previewed her iconic song "Like a Virgin."

7. Performance

Keith Haring, Red Room, 1988. Acrylic on canvas, 243.8 × 454.7 cm. The Broad Art Foundation. © Keith Haring Foundation.

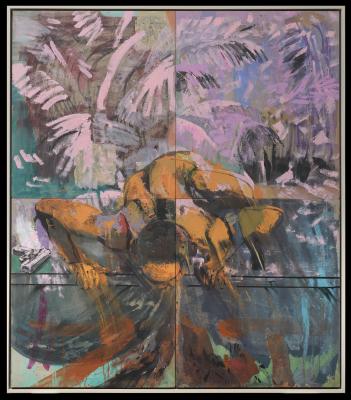

Haring was no stranger to live performances. As an art student in New York, he took to the subway to create art in blank advertisement spaces, an act he saw as a form of performance.

In 1983, he became friends with dancer and choreographer Bill T. Jones and began collaborating with him for live performances, such as in the performance Long Distance (1982). In this performance, Bill T. Jones dances while Haring paints behind him. Haring’s brushstrokes and noise from the street outside are the only sounds accompanying Jones as he dances. A short clip of this performance plays in Room 6 of the exhibition.

Haring drew Red (1982 and 1984) during one of his performances with Jones, which is currently on view in the exhibition in Room 7. Bill T. Jones will be in conversation at the AGO on March 5, 2024. Grab tickets here.

Keith Haring: Art is for Everybody, on view now until March 17, 2024, on Level 4 of the AGO. For more information on each room in the exhibition, see this PDF.

The exhibition is organized by The Broad, Los Angeles and curated by Sarah Loyer, Curator and Exhibitions Manager, The Broad. The AGO's presentation is curated by Georgiana Uhlyarik, AGO's Fredrik S. Eaton Curator of Canadian Art.

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)