Five moments in Caribbean-British art and history

Learn more about the Caribbean-British history fueling the art on view in Life Between Islands

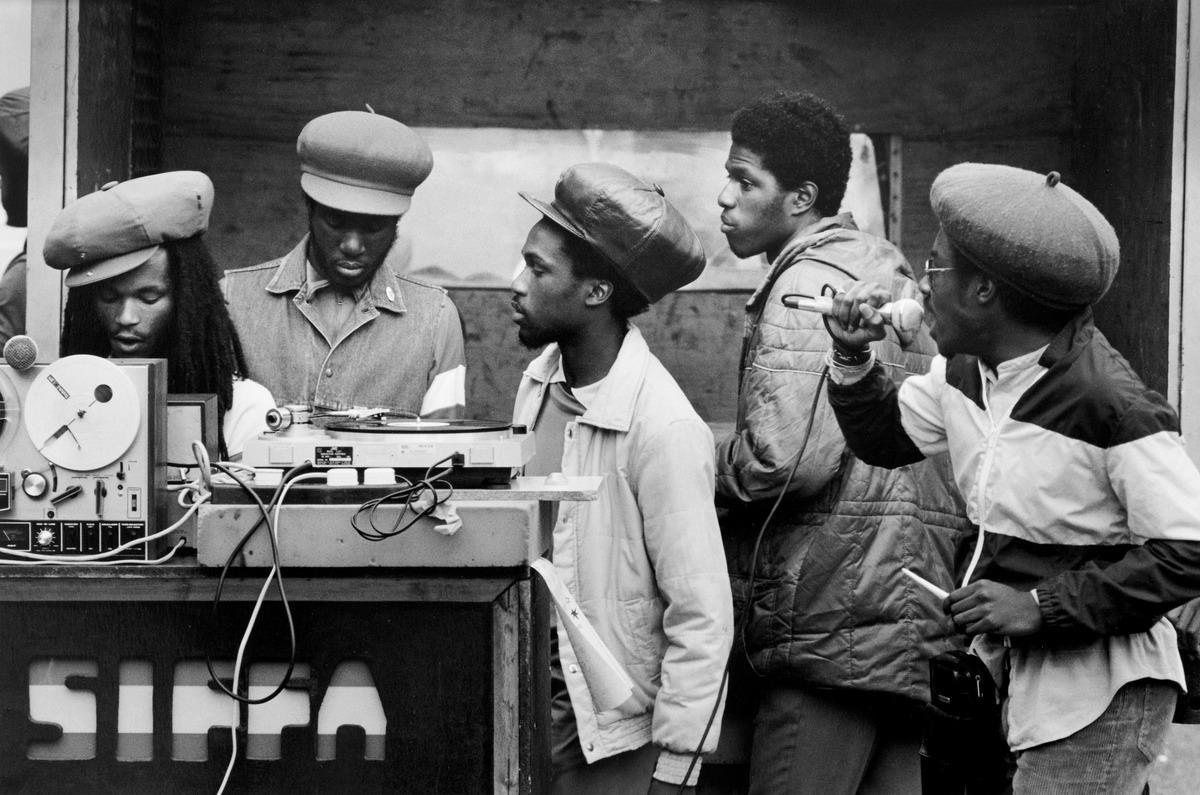

Vanley Burke. Siffa Sound System, Playing the Carnival, Handsworth Park, 1983, printed 2023. Gelatin silver print, 63.5 × 78.7 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Vanley Burke.

If you live in Canada, especially in Toronto, you will know firsthand how influential the Caribbean community has been on the country’s culture. From the beloved Jamaican patties to commonly used lingo and carnival festivals every summer, Caribbean culture is a vibrant part of the everyday lives of many Canadians, whether they realize it or not.

Comparable contributions to food, music, and culture are also evident in the United Kingdom (UK). Currently on view at the AGO, Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art, 1950s-Now is dedicated to highlighting another important contribution to UK culture that often gets overlooked: art. Originating at Tate Britain, the exhibition guides viewers through decades of art created by Caribbean artists in Britain, showcasing an expansive range of mediums including sculpture, painting, documentary photography, and film.

As viewers enter the exhibition, they’ll move through four loose chronological sections, examining how topics such as decolonization, discrimination and sociopolitical conflict, cultural reclamation, and Caribbean diasporic identity have been explored by Caribbean-British artists over time. “Arrivals” is dedicated to the works of artists from the 1940s-1970s Windrush Generation while “Pressure” highlights the second-generation — Caribbean artists born in Britain or those who emigrated as young children. “Caribbean Regained: Carnival and Creolization” is dedicated to reimaging Carnival traditions at different time periods and a range of mediums. “Past, Present, Future,” draws connections across time, featuring recent works encompassing the themes and history explored throughout the exhibition.

Given the exhibition’s focus on time and the way history continues to inform the present, Tate Britain created an accompanying timeline highlighting important moments in Caribbean-British art, culture, and society. While not a comprehensive list of all Caribbean-British history, it provides insight into key events happening simultaneously with the creation of works featured in the exhibition.

Here are five highlights from the timeline and five works from the exhibition connected to these historic events.

1940s: The Windrush Generation

While the exhibition’s title suggests that it starts in the 1950s, the 1940s are an important precursor for understanding the works featured in Life Between Islands. This decade saw mass migration from the Caribbean and the first large group of Caribbean immigrants transported on the HMT Empire Windrush in 1948. Named after this ship, the term “Windrush Generation” encompasses Caribbean people who emigrated to the UK between 1948 - 1971. This mass migration was encouraged by the British Nationality Act which allowed anyone born in a British Empire to become a citizen of the UK. In reality, the act was created to address labour shortages in the UK.

The 1940s was also a time of political and cultural transformation in the Caribbean, with an influx of workers unions and grassroots organizations being established. Art and culture became more widely accessible due to organizations such as Guyana’s Working People’s Art Class (WPAC).

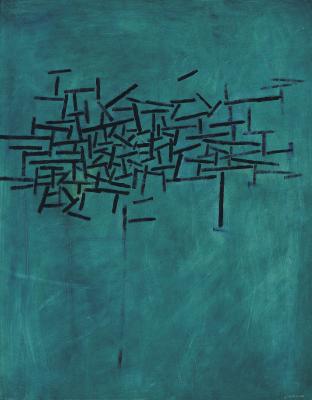

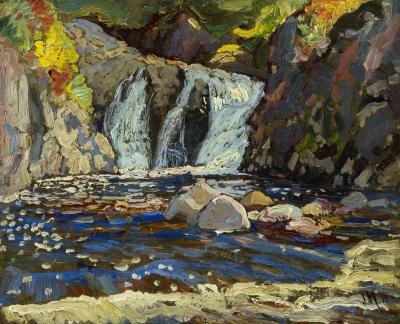

Donald Locke (1930 - 2010), as well as his fellow Guyanese contemporaries Aubrey Williams (1926-90) and Denis Williams (1923-98), got their start at WPAC and all emigrated to the UK in the late 1940s and early 1950s. While he was at the WPAC, Locke discovered his love of art, and in 1954 he won a scholarship to study in Edinburgh, Scotland.

Donald Locke. Plantation K-140, 1974. Ceramic, wood, steel, acrylic sheet, carpet and laminate, Overall: 32 × 38.1 × 33 cm. Tate. Purchased 2021. T15768. © Estate of Donald Locke.Photo: Tate.

Locke’s work Plantation K-140 (1974) is part of his plantation sculpture series and is named after a plantation in Guyana. Locke organizes objects in strict lines and imprisoned grids to symbolize the structures that maintain economic and political subjugation. The work of Locke’s son, Hew, is also on view in the exhibition.

1950s: The birth of Notting Hill Carnival

The Notting Hill Riots occurred in 1958 following two weeks of racist attacks and rioting in West London. Large numbers of white youth attack Caribbean immigrants and damage their homes. A year later, Claudia Jones organized a Caribbean carnival in response to the riots, marking the birth of the iconic Notting Hill Carnival which attracts 2 million attendees today. Toronto’s own festival, Caribana, began in 1967 and continues to attract large crowds annually. Taking place across the Atlantic, these festivals became important sites to celebrate Caribbean culture and Black cultural and political resistance.

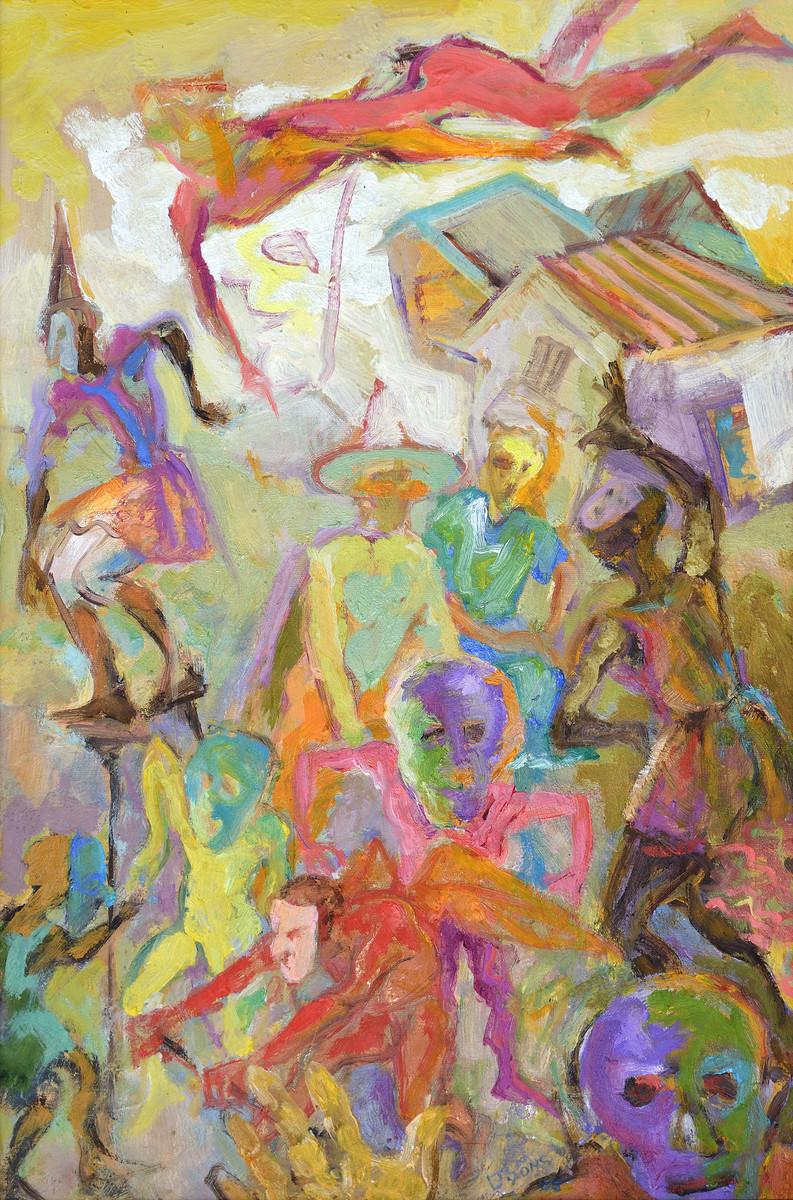

John Lyons, Carnival Jouvert, 2005. Oil on canvas, Overall: 68.6 × 49 × 2.5 cm. Halamish collection, London (courtesy of Felix & Spear Gallery). © John Lyons, courtesy of Felix & Spear Gallery.

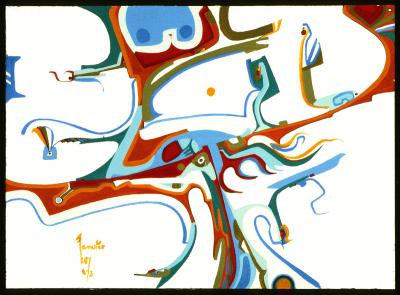

John Lyons moved to England in 1959 to study art. Lyons’s art is heavily influenced by his childhood in Trinidad, specifically the Carnival scene. Painting with bold colours and dreamy pastels, his paintings capture the energy of Carnival. In Carnival Jouvert (2005), Lyons depicts the start of Carnival in Trinidad called “J’Ouvert” or jouvay, which translates to “break of day” in French creole. Speaking on the painting, Lyons notes that it was inspired by the memory of revelers pouring onto the street after the Monday morning church bells to dance on the street.

1960s: The Caribbean Artists Movement

The 1960s became a momentous time for islands in the Caribbean, with Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago gaining independence in 1962, and Guyana gaining its independence in 1966. Occurring around the same time, the Caribbean Artists Movement (CAM) was established in 1966 in the UK. Co-founded by Aubrey Williams, CAM assembled an alliance of artists, writers, and critics who aimed to create a decolonized and modern outlook on Caribbean art and culture. The ultimate aim for CAM artists was to return to their respective Caribbean countries to help further decolonize art and culture, but the conversation shifted to highlighting racism in the UK.

CAM also included numerous artists on view in Life Between Islands such as Ronald Moody (1900-1984), Paul Dash and Althea McNish (1924-2020), the only woman in the organization.

1970s: Growing Racial Tension

The 1960s and 1970s were heavily marked by civil unrest and racial tension in the UK. In 1970, The Mangrove, a popular Caribbean restaurant in Notting Hill, West London, acted as a meeting space for the Black community. However, the restaurant was subject to constant surveillance and targeting by the police. In response to the harassment, protests were mounted and nine activists, known as the Mangrove Nine, were charged with rioting before they were cleared of all charges in 1971. In 1976, a riot broke out at the Notting Hill Carnival due to increased police surveillance and racial profiling, injuring 100 police officers and 60 members of the public. Called the Battle of Lewisham, in 1977, 500 members of the far-right group The National Front marched through Black neighbourhoods and were met with a counter-protest of 5,000 people.

Life Between Islands features a range of British-Caribbean photographers who documented the tension of this decade, including Ingrid Pollard, Vanley Burke, Isaac Julien, Neil Kenlock, and Sir. Horace Ové, who directed Pressure (1976), which is considered the first British feature by a Black director.

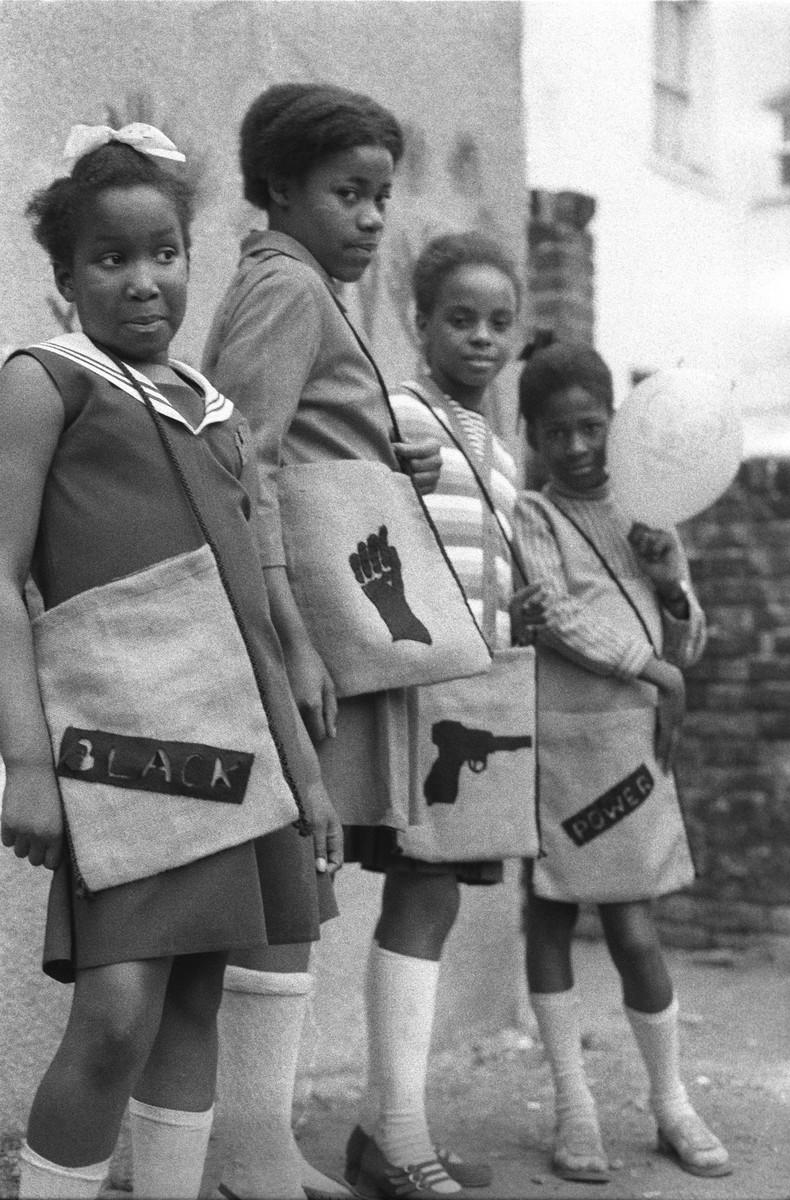

Neil Kenlock, Black Panther school bags, 1970, printed 2010. Gelatin silver print, Overall: 38.1 × 25.4 cm. Courtesy of the Neil Kenlock Archive. © Neil Kenlock

Neil Kenlock became the British Black Panther’s photographer, documenting the group's activism throughout the 1960s and 1970s.

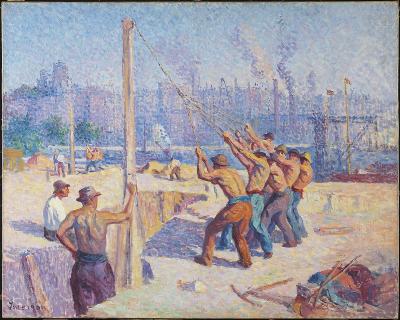

1980s: Black Arts Movement (BAM)

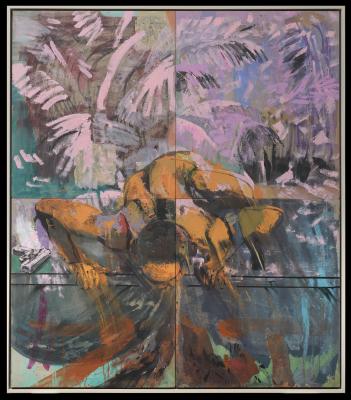

While CAM dissolved in 1972, the Black Arts Movement (BAM) was formed in 1982 and became one of the most influential dimensions of British Art in the 1980s. Artists in BAM explored Black Britishness, diasporic identities, legacies of colonialism and slavery, systemic racism, and the intersections of race, gender, and identity.

Denzil Forrester. Jah Shaka, 1983. Oil paint on canvas, Overall: 213.4 × 274.3 cm. Collection Shane Akeroyd, London. © Denzil Forrester, courtesy Stephen Friedman Gallery, London and New York.

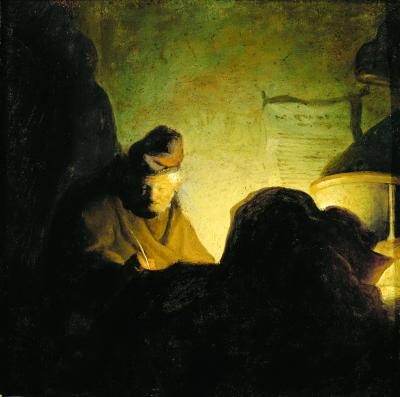

Carnival, sound systems facilitated by DJs, engineers, and MCs along with reggae and the formation of Dub, a subgenre of Reggae, were subjects also commonly explored by Caribbean-British artists. Denzil Forrester’s oil painting Jah Shaka (1983) takes viewers inside London’s Dub-Reggae scene, depicting Jamaican Sound System Operator Jah Shaka, who was based in Southeast London. Forrester’s work examines how Rastafarianism and Dub music are rooted in West African oral traditions of storytelling and music. Forrester would sketch his outlines to the music playing inside clubs, and then finish the painting at home using carnivalesque colours to represent the energy of the crowds.

2020s: Black Lives Matter

The murder of George Floyd in 2020 prompted the most recent wave of Black Lives Matter demonstrations, with protestors taking to the streets amid the COVID-19 pandemic across the world, including in the UK and Canada.

Floyd’s murder, alongside the pandemic which saw disproportionate death rates among Black individuals, became important catalysts for Black communities to reexamine the continuing effects of slavery and colonialism while also questioning how to address these legacies.

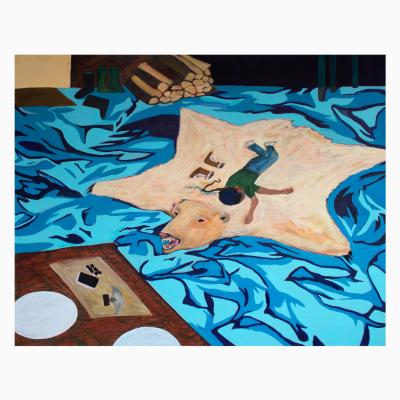

Alberta Whittle. We Remain With You, 2022. Raffia, acrylic, cotton, synthetic braiding hair, doillies, wool, felt and cowrie shells on linen, Overall: 172.7 × 165.1 × 20.3 cm. Courtesy of Alberta Whittle and Nicola Vassell Gallery © Alberta Whittle. Photo: Adam Reich Photography

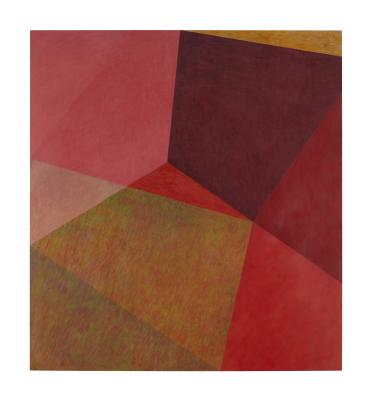

Interdisciplinary artist Alberta Whittle uses performance art and textile works to explore the influence of colonialism on the Black and Caribbean diaspora. In We Remain with You (2022), Whittle uses raffia palm leaves alongside fabric from her family archive to create a figure with open arms. For Whittle, collective care and compassion are crucial ways to resist anti-Blackness and racism. The figure, dressed in attire related to of carnival and Barbadian Tuk Bands, is a symbol of protection and guidance.

_______

Courtesy of the Tate Britain, read the full version of A Caribbean-British Timeline: Art, Culture and Society here. Please note, this is not a comprehensive timeline, but rather provides context for the exhibition.

Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art, 1950s - Now is on view on Level 5 of the AGO until April 1, 2024. Life Between Islands was organized by the AGO and originated by Tate Britain, Co-Curated by David A. Bailey, Director, International Curators Forum, and Alex Farquharson, Director, Tate Britain. The AGO presentation is overseen by Julie Crooks, AGO Curator, Arts of Global Africa and the Diaspora.

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)