An Interview With Rae RezWell and Peter Owusu-Ansah

Two artists explain how their deafness informs their relationship to art as they reflect on Helen McNicoll

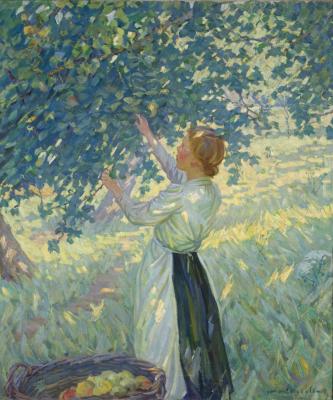

Helen Galloway McNicoll. The Brown Hat, c. 1906. Oil on canvas, Framed: 75.5 x 65.5 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift from the Estate of R. Fraser Elliott, 2006. Photo © AGO. 2006/88.

While the visual nature of painting, photography, and drawing seems to only communicate with our eyes, the role our ears play in seeing, understanding, and creating art may not be obvious to everyone.

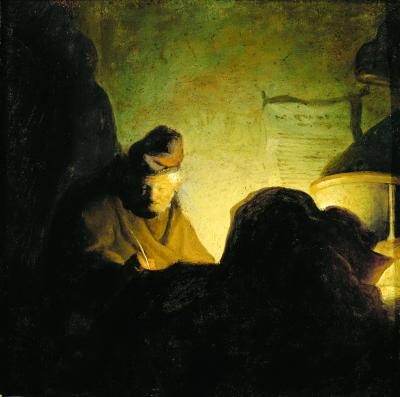

Take, for example, the work of Canadian painter Helen McNicoll (1879-1915) on view now as part of the AGO exhibition Cassatt - McNicoll: Impressionists Between Worlds. Born in Toronto, Ontario, McNicoll contracted scarlet fever and became deaf at the age of two. According to art historian Samantha Burton, she navigated the art world through lip reading and the support of friends and family. While McNicoll faced barriers, ultimately the privilege of having a wealthy family helped her establish her painting career.

To better understand how her deafness may have affected her experience as an artist, Caroline Shields, the exhibition’s curator, and Gillian McIntyre, the exhibition's interpretive planner, invited Canadian Deaf artists Rae RezWell and Peter Owusu-Ansah to share their reactions to McNicoll’s work.

Mixed-media photographer Rae RezWell. Image courtesy of Rae RezWell

Visual artist Peter Owusu-Ansah. Image courtesy of Peter Owusu-Ansah.

Stepping into the AGO’s vault to see McNicoll’s paintings ahead of the exhibition, Owusu-Ansah and RezWell noted McNicoll’s skillful use of light, colour, and movement, seeing these aspects of her paintings as both a way to communicate with the world and a vivid expression of her lived experience as a Deaf artist. Their conversation was documented in a video and included in the exhibition.

Building on this, Foyer wanted to dig deeper into how their lived experiences not only affect how they create art, but also how they perceive McNicoll’s paintings and visual art in general. Here’s that conversation.

Foyer: Before we talk about your thoughts on Helen McNicoll, can you each tell me a bit about your own work as artists and what inspired your journey with art?

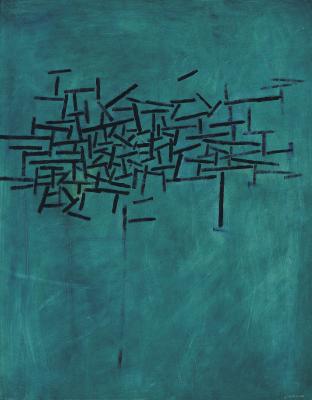

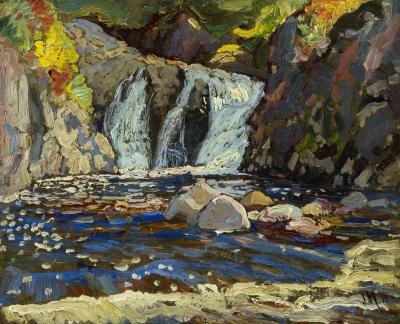

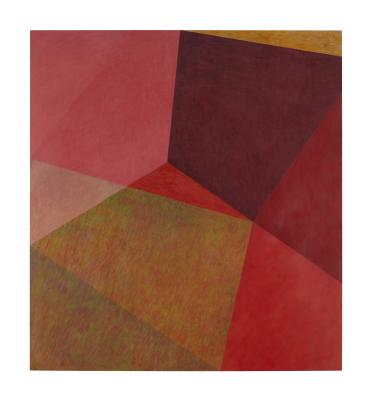

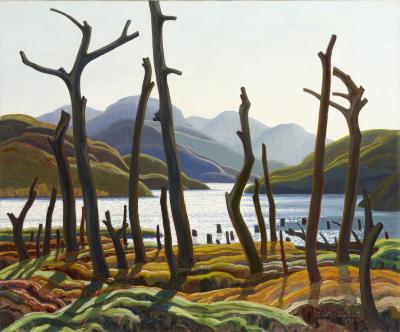

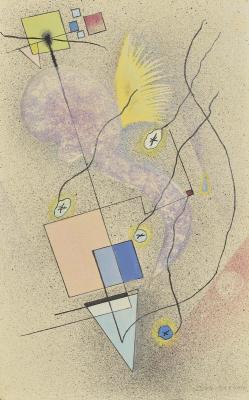

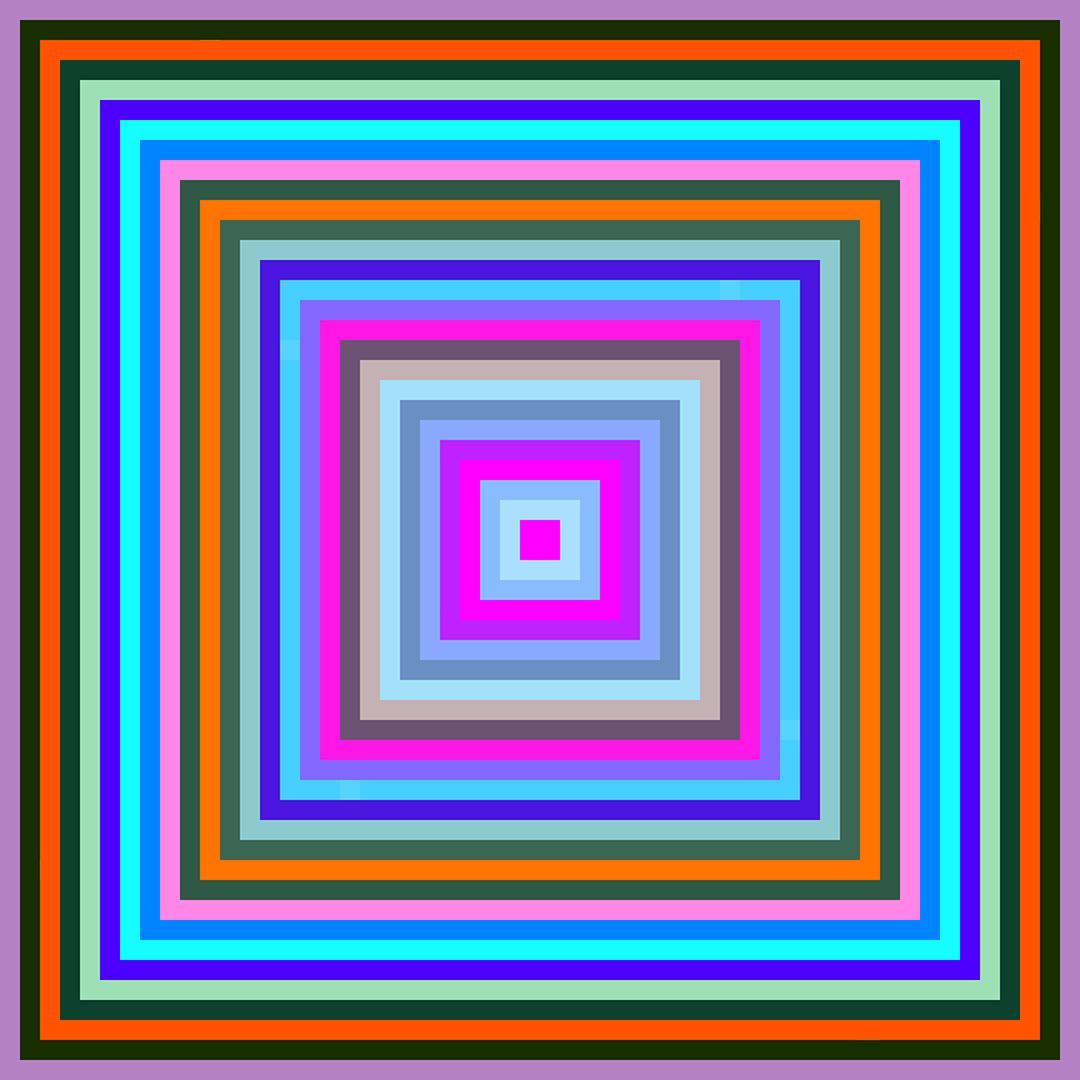

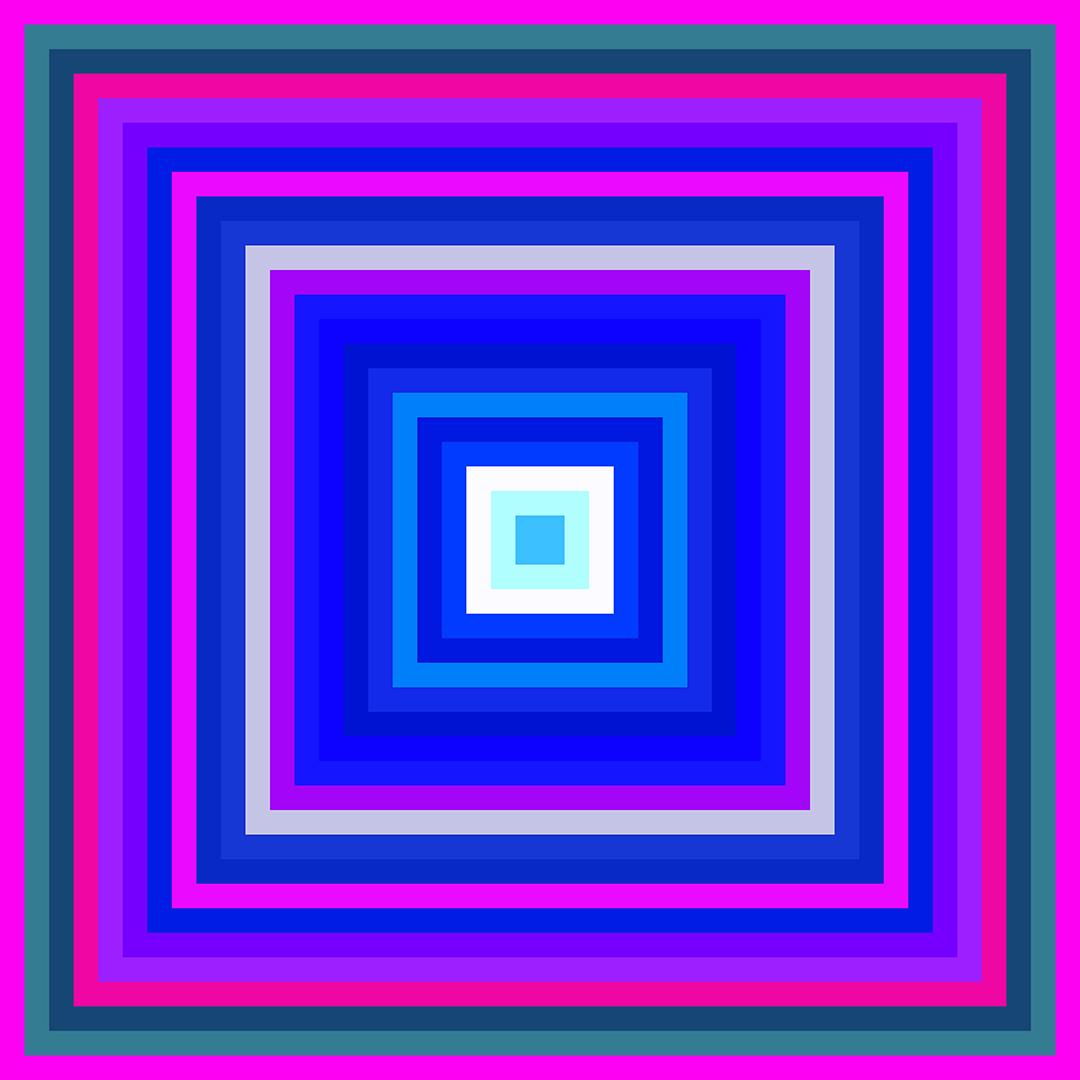

Owusu-Ansah: I’m a visual artist, and what inspired my journey into the art world is colour. I did a lot of digging and self-reflection and I feel like my specific journey in life here on earth is very visually attuned. There’s something about colour that really resonates with me and without it, I feel lost. I wanted to dig deeper into why that is. I was already aware of Josef Albers' Homage to the Square and Frank Stella’s minimalism. I was curious to see what it would be like doing it as a Deaf artist — what can come from me? While I was going through the process and trying to figure out a good reason to create this style of work, I became passionate about these examples because I don’t see a Canadian vision or a Black artist's vision of this type of work. I felt that there was an opportunity to make it happen and I did just that.

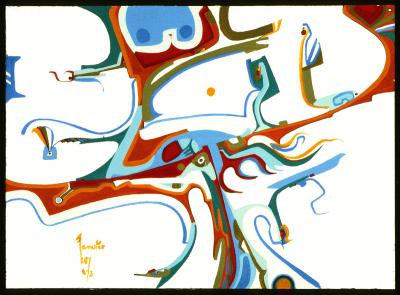

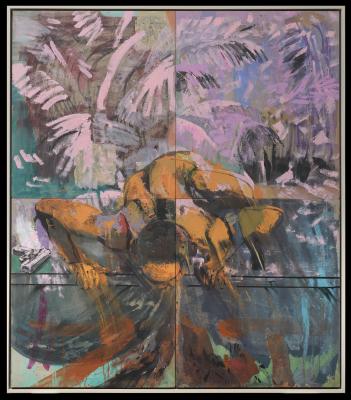

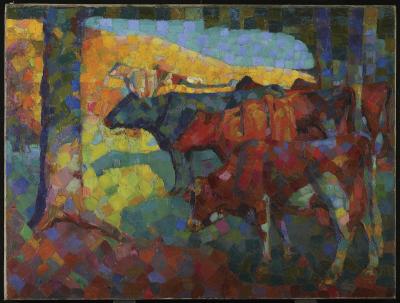

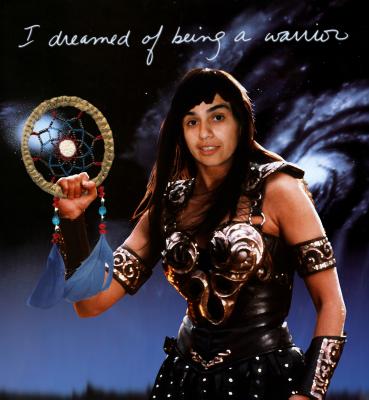

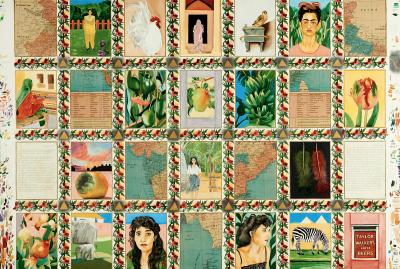

RezWell: I’m a mixed-media photographer and I don’t focus on one medium. I incorporate a number of different artistic mediums, materials, techniques and colours. The reason why I work with so many mediums and materials is because of my background and the varied cultures I embody. I am a mixed-race person with a mixed ancestry and my art shows that intersectionality. I don’t like the concept of boundaries, so I think that’s why my artistic work is so varied. From a very young age being the only deaf person in my family, I had to figure out on my own how to survive. Having cochlear implants fitted when I was young, communication was such a huge struggle. During that time, I used art to express myself and I think that’s where the inspiration to start my artistic journey came from — it was a way to express who I am, what I’m feeling, and a way to escape from the real world. It’s also a way to relate with other people who might have shared intersectional identities.

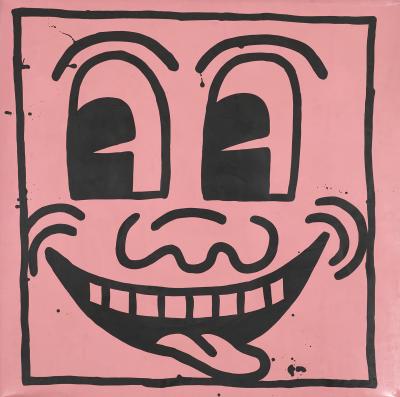

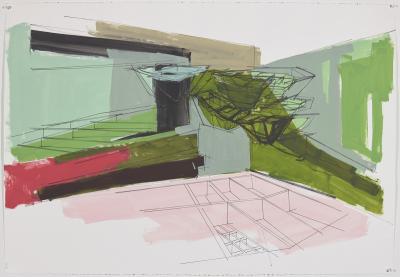

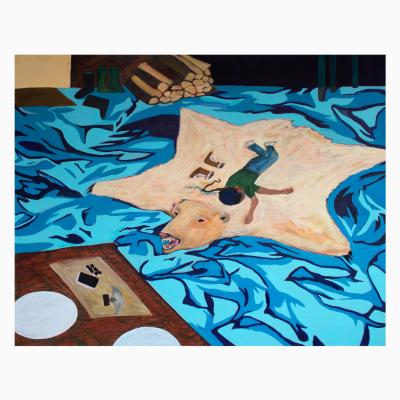

Peter Owusu-Ansah, Ecstasy Wave, (2022). Image courtesy of Peter Owusu-Ansah.

Foyer: Going into the vault to see McNicoll’s work before the exhibition opened, what were your first reactions to her work? Was it your first time seeing McNicoll’s paintings?

Owusu-Ansah: Yes, it was my first time. When I first saw McNicoll’s work I felt a bit of relief because [it was the first time I saw] a Deaf artist’s work featured at the AGO since I first learned about it in 2005. When I found out about the AGO, I started to come on occasion to see different artworks and I've been through Toronto and visited different galleries. [Seeing McNicoll’s work,] what really impacted me, something I hadn’t seen before, was art that expresses the Deaf experience. Historically, artwork has been hearing-centric and represents the experience of hearing people. When I came [to the AGO] in 2005, it was a bit of a revelation for me. I felt like ‘Oh, okay, here's a space that I can inhabit,’ and I told myself what we need here is work like McNicoll’s or someone who represents that experience of a traditionally marginalized group.

There’s also a negative side to this. There’s that aspect of relief that finally there has been a breakthrough for Deaf artists, but [McNicoll also comes from] a wealthy family, so people who aren’t of that same status or class don’t get those opportunities. McNicoll came from a wealthy family, which gave her opportunities, and now her artwork is being shown. But what about people who don’t have that wealth?

RezWell: I’ve seen some pieces, but I had never seen McNicoll’s work in a gallery setting. I had also never seen someone who is part of the Deaf and Hard of Hearing community have their work displayed in a formal gallery, so that was also a new aspect to me. I agree with Peter — seeing McNicoll’s work it was like finally, we’re starting to see some artists that have our lived experience. Deaf artists don’t typically get opportunities. There are a few here and there, mostly in the United States, but in Canada, there aren’t many opportunities for Deaf artist to display their work. I think now that there's more of a focus on Deaf artists, there might be more opportunities in the future for us, such as this exhibition which is great because I wasn't really aware of this artist before. There have been Deaf artists; they just have not been spotlighted.

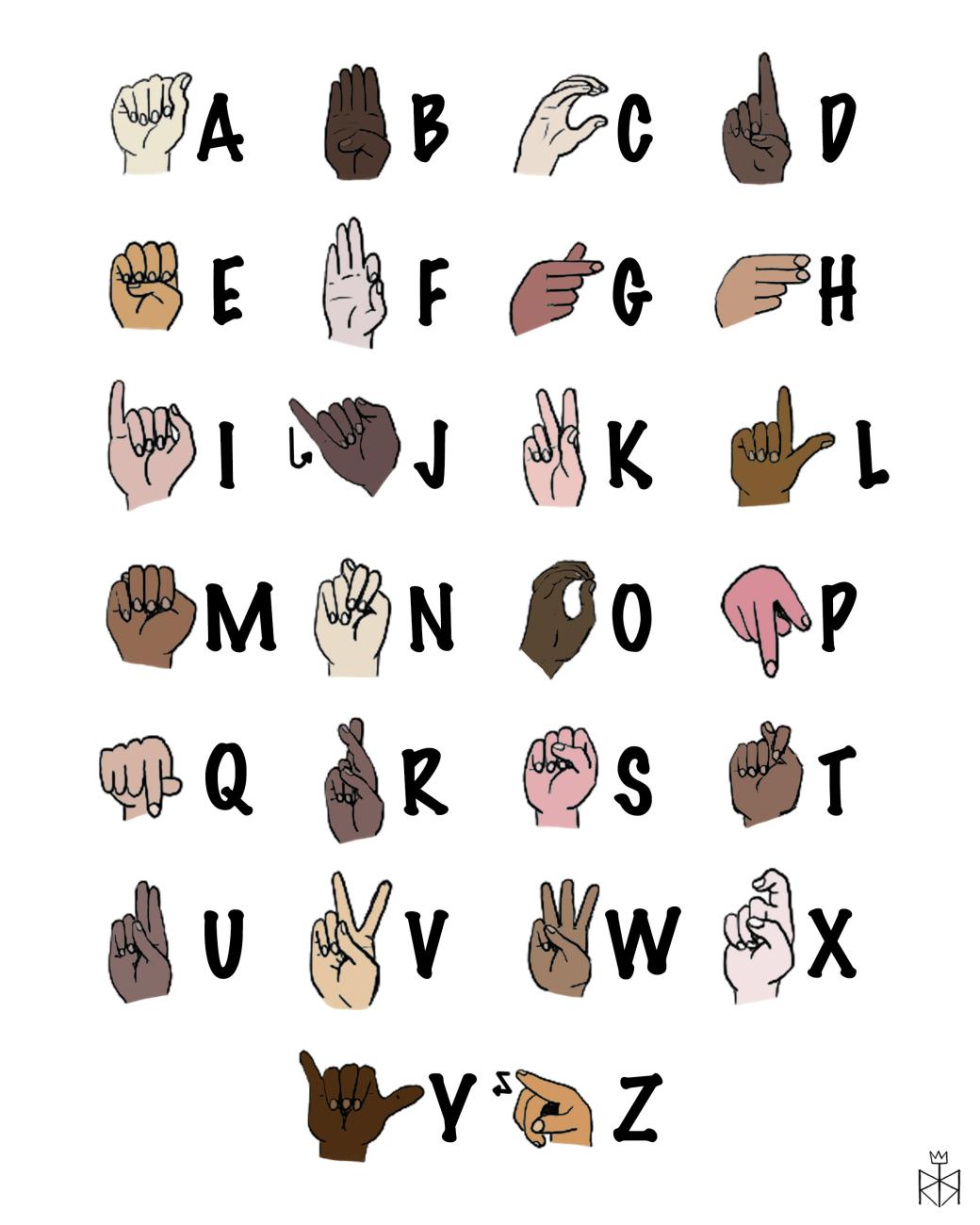

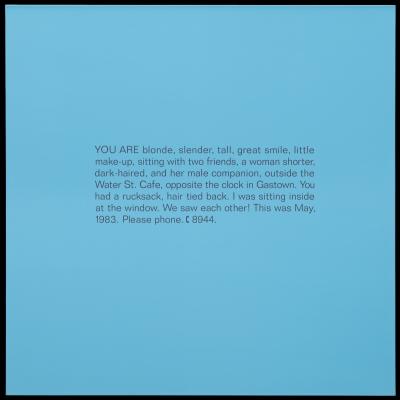

Rae Rezwell, Rae's ASL Font with Letters, (2022). Image courtesy of Rae Rezwell.

Foyer: McNicoll’s paintings are quite different from both of your personal artistic styles. In the video, you talk about how by looking at her paintings, you could get a sense of McNicoll’s values and how they informed her artistic choices. In reflecting on her work, did either of you find any parallels to your own work or values?

Owusu-Ansah: Well, values for work, yes. Colour and possibly light inform my work, so those are parallels [with McNicoll]. But in terms of style — trees, people, and that sort of subject matter, that’s where we differ. The reason I say light and colour are similar in our artistic styles is because I think we use that to communicate with the audience. Since it’s visual, you don’t have to hear light or colour. You can communicate through those two pieces to convey meaning.

RezWell: Yes and no for me. Mine and McNicoll’s values and approaches are very different. My experiences as a Deaf person in my childhood are what I express through my art. McNicoll’s paintings are a different style. They’re painting more so to express an artistic skill, rather than having a social message. So, I think those are the points where we differ.

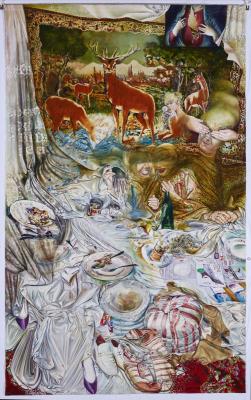

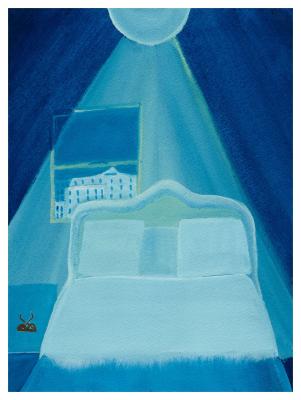

Rae RezWell, Embrace the Spark and Bloom, (2022). Image courtesy of Rae RezWell

Foyer: In your discussion of McNicoll’s work, both of you focused on her nuanced use of light, colour, and especially her attention to movement and gesture as reflective of how she experienced the world. How does your lived experience influence how you perceive and create art?

Owusu-Ansah: I am looking at the world and I see that much of the world knows almost nothing about the experiences of Deaf and Disabled people. I feel that it’s important for the world to experience our art because that will help viewers better understand deafness and disability, rather than continue to hold the same colonial views which have had a negative impact on Deaf and Disabled people's lives for generations and generations to come. This experience and perspective on life are what influences my journey.

For McNicoll, I imagine she would see the world the same way that I do. I think she probably didn’t feel like her identity as a Deaf person counted in society or felt like she was being included in the culture of her time. She probably felt that since she couldn’t communicate through hearing, she could communicate through vision. McNicoll had the skills to express Impressionism which was popular during her time. She may have noticed the popularity of Impressionist paintings at the time and took the opportunity to use her artistic expression to show that just because she was deaf, it didn’t mean she wasn’t capable of doing anything great. Another battle she faced was being a woman. Women didn’t have the same rights as men during her time. I think all the emotion behind her experiences is seen in her work.

RezWell: I can imagine that when McNicoll got into art, she had the visual acuity to notice things in the moment. I remember when I was young, and up until now, how impactful anything visual was. I’m able to see movement, light, and colour in a different or deeper way than perhaps other hearing people would experience. In my opinion, each Deaf person really relies on their eyes — those are part of our value system. I believe we can see colours in a different way compared to hearing people. I remember the moment my cochlear implants were in and what it was like to hear language and feel sound. I compared this experience to being a Deaf person who’s extremely visual and can imagine the impact hearing or not hearing would have on a person’s life and how they express themselves through their art. I believe Deaf people tend to be more sensitive to different smells, colours, tastes, and light compared to a hearing person who depends on their ears. We’re doubly focused on the world through our other senses and we can see things that other people don’t tend to pick up. I think it’s how our brains are wired because we’re relying on our vision.

I think being a Deaf person growing up in a world of hearing people and being more visual is similar between McNicoll and me, but where we differ is a lack of access. McNicoll was lucky because she had opportunities and had a wealthy family to support her, whereas to this day there are still barriers [to the art world] that people with disabilities face. I think having to navigate those barriers as a Deaf person is different compared to McNicoll’s time and mine. As much as there are similarities, there are differences in our artistic styles and the conditions we lived in.

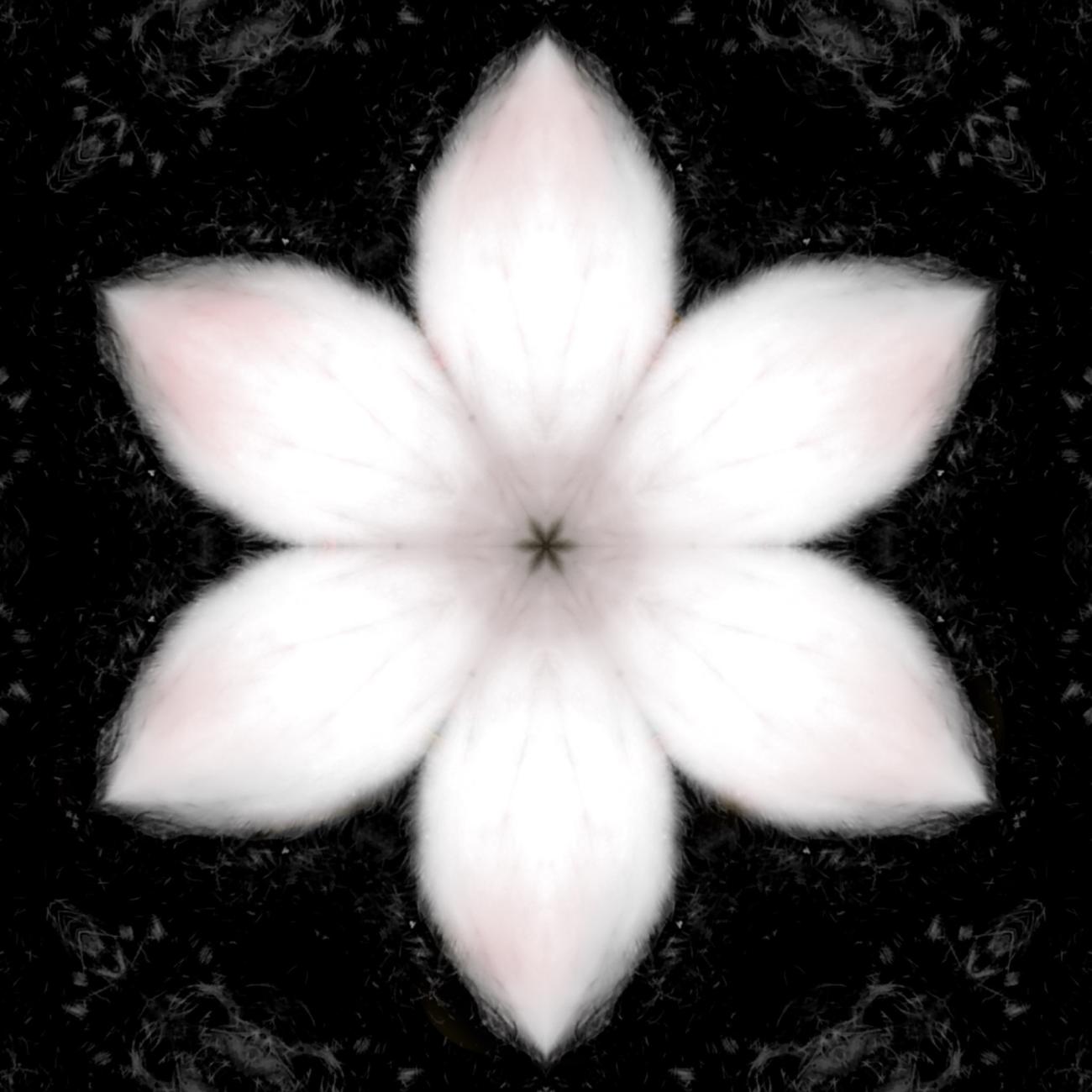

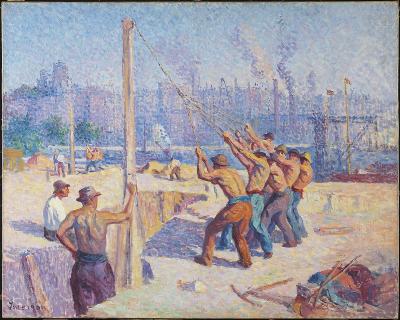

Peter Owusu-Ansah, White Bulb, (2023). Image courtesy of Peter Owusu-Ansah.

Foyer: In the video, you also discussed how McNicoll’s paintings, specifically her use of colour and light, may have been her way of communicating not only with her hearing contemporaries but also with the world at large. Do either of you feel like your work accomplishes a similar goal? Is there a specific message you’re aiming to communicate through your work?

Owusu-Ansah: Yes, I believe I have accomplished a similar goal as McNicoll. However, I think her works may not be as engaging to younger audiences as my works are. My work is for anyone. I aim to communicate the pure joy of seeing colours as a Deaf artist. If you see my works and find joy in them, that is exactly the type of communication I am expressing. I also aim to promote the existence of Deaf artists through my work. When you enjoy my work, you are actually seeing a work by a Deaf artist. Even if you are not asking who the artist is, you are still looking at the work of a Deaf artist. If you ask who the artist is, then my Deafness will reveal. I would like for everyday people to learn about Deaf and Disabled people because being invisible in society with people not learning anything about our experiences makes us feel like we don’t exist. People continue to hold the colonial definition of who we are and that continues to do damage. I want platforms to give us an opportunity to express ourselves from our perspectives. I think this is the best way to educate each other as human beings.

RezWell: My focus is more on a general audience. I’m not specifically speaking to any particular group of people. My themes tend to be along the lines of advocacy for people who have shared my experience and those who don’t but want to learn about how I experienced the world. My work is not just for Deaf people across the spectrum including those who are hard of hearing and more. It’s for people who come from diverse backgrounds: those who are Black, Afro-Latinx, mixed race, Indigenous, or have multiple races or exist at many intersectionalities. It’s for people who want the opportunity to look at art and learn something new because of something I’ve made. They can see a person’s experiences represented, and they can learn from that. It’s about building perspectives and showing a different way of being and then perhaps sparking a discussion from the artwork.

See RezWell and Owusu-Ansah’s video in conversation with McNicoll’s paintings and sketches in Cassatt – McNicoll: Impressionists Between Worlds, on view now until September 4 in Sam and Ayala Zacks Pavillion, located on Level 2 of the AGO. This exhibition was curated by Caroline Shields, Curator of European Art at the AGO, with Gillian McIntyre as Interpretive Planner.

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)