Jinny Yu on the guest/host dynamic

The acclaimed artist discusses the colours and shapes of her debut AGO solo exhibition

Jinny Yu with her work, Inextricably Ours 23-07, 2023. © Jinny Yu. Photo: Craig Boyko © AGO.

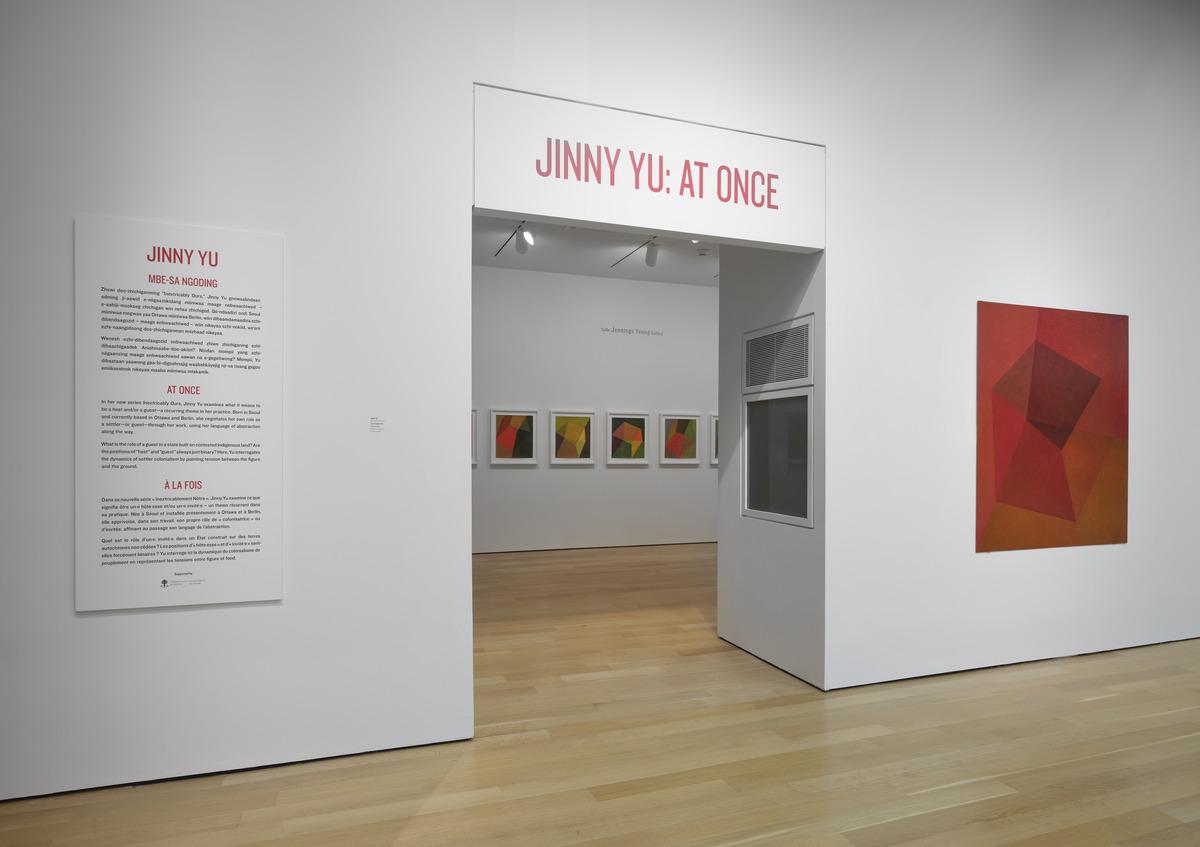

What does it mean to live as a guest on Indigenous land? Due to the realities of settler colonialism, all non-Indigenous people in Canada must confront this question. After immigrating to Canada from South Korea in 1988, contemporary artist Jinny Yu views herself as an invited guest of the Canadian government, while simultaneously being an uninvited guest of this land’s original inhabitants. For over ten years, Yu has been vigorously unpacking this complex dynamic through her practice. Her new solo exhibition at the AGO exemplifies exactly that.

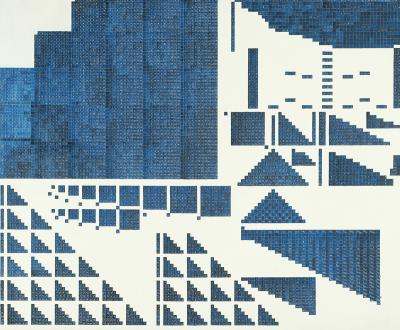

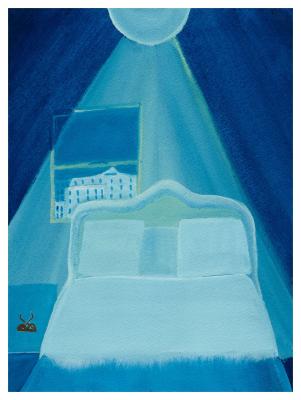

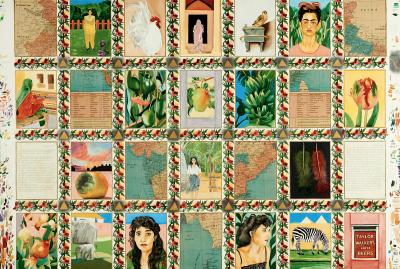

On view now at the AGO, Jinny Yu: at once features 22 new works, including paintings with oil on aluminum and works on paper all from her ongoing series Inextricably Ours. The exhibition is curated by Georgiana Uhlyarik, Fredrik S. Eaton Curator of Canadian Art, AGO. Yu embraces the use of vivid colour, transparency and distorted forms as a new way to continue her exploration of the guest/host dynamic.

Based between Ottawa and Berlin, Yu has been a professional artist and educator for the past 20 years. In 2017, she began to examine her settler identity with Perpetual Guest, a series of works on untempered glass, deliberately installed on the floor to direct the viewers’ gaze down toward the land. In 2020, Yu released an artist book featuring her drawings titled Hôte exploring the idea of a door opening to varying degrees to consider the shared responsibility between guest and host. Inextricably Ours is Yu’s most recent take on this profoundly complex and ongoing investigation, inspired by Edwin Abbott’s 1884 novella Flatland: A Romance with Many Dimensions.

Yu spoke to Foyer about her recent shift towards colour, the multifaceted nature of the guest/host dynamic, and the future of an ongoing series she sees as far from complete.

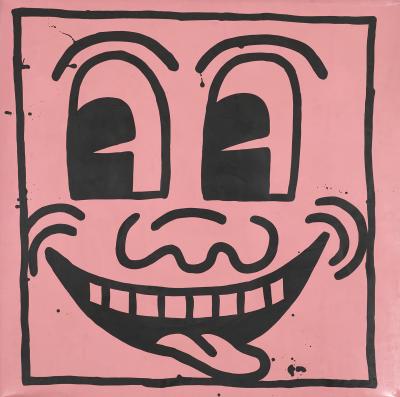

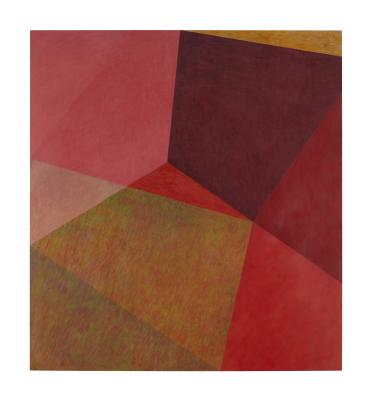

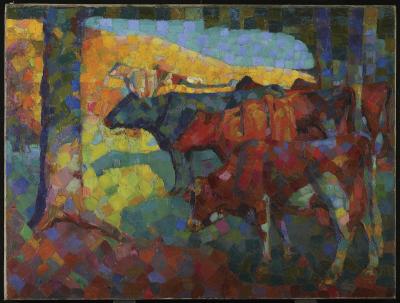

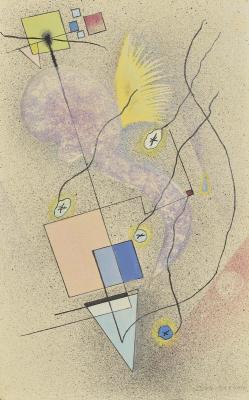

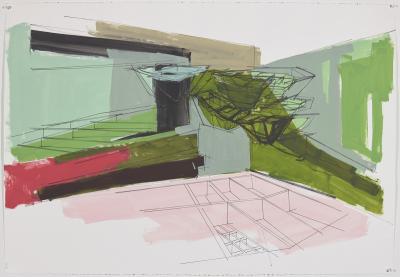

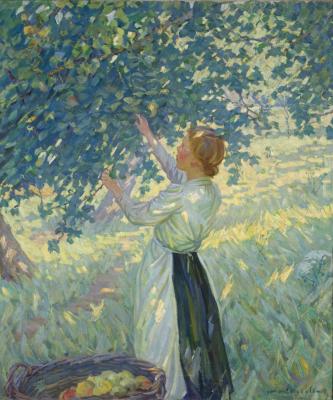

Jinny Yu. Inextricably Ours W22-05, 2022. Watercolour on paper, 48 × 43.9 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Jinny Yu. Photo: Aylin Abbasi

Foyer: Considering your last decade of your work, Inextricably Ours represents a major transition into color for you. Can you talk about your decision to shift into colour, and why you felt drawn to these particular colours?

Yu: I have used only black paint from 2009 until 2020. That was because I did not need colour. I felt that painting was a verb and not a noun, so I just needed action to be shown on a surface; brushwork was enough for a work to be a painting. It was my way of being reductive and bringing down painting to only what was essential. Black came to me naturally because I was thinking about ink, Korean ink, for example, being primarily black. And, in colour theory, black is a combination of all colours and moreover offers a very wide range of gradation. So black seemed to me like a natural choice of colour or “non-colour” to use for the last 11 years or so.

Then the pandemic happened. Black Lives Matter happened. It was a period of reflection. I began rethinking the colour black that I was using and questioning the socio-political implications of using black as being a relatively recent settler of Asian descent on this Indigenous land. What does it mean that I use only black in my paintings? I started to read about the colour black in abstraction and its socio-political implications, starting with an article by Jared Sexton called “All Black Everything” first recommended to me by Tammer El-Sheikh. In 2020, there was a racist incident at the institution where I work. The fact that it happened made me angry, but the way it was handled made me even angrier. I suggested to my colleagues that the very least we could do in response was to teach the works of more BIPOC artists in our courses. The response I got was, “Oh, they're so hard to find.” I decided to start a project called Canadian BIPOC Artists Rolodex, which is a database of Canadian BIPOC artists, with my colleagues Celina Jeffery and Ming Tiampo. The energy that I put into this project – which is part pedagogic and part activist – somehow lifted the pressure I used to feel having to put everything in my artwork and say everything with it. I started to feel somewhat liberated and freer.

At around the same time, Georgiana [Uhlyarik] gifted me a set of watercolour stones made by Beam Paints, a paint manufacturing company founded by Anong Beam [daughter of artists Carl Beam and Ann Beam]. The set consisted of four paint stones in blueish-gray tones. I started to do some sketches in the studio with one of the colours, feeling it out little by little. Shortly after I started to do these sketches, I was invited to do a residency in Côte d’Azur in La Napoule, to which I brought 15 pieces of paper and some watercolours for the ease of transport. And colour just exploded when I got to Côte d’Azur. The Mediterranean light is something that I could not resist while there for a month. Some other things happened in my life and I was naturally led back to using colour.

With Perpetual Guest, you were thinking about your position in Canada as an invited guest of the Canadian government, who are themselves uninvited guests on Indigenous lands. Then, in Hôte, you were examining the interplay within this guest/host dynamic. Considering the new works in Inextricably Ours, how would you say your lens on this topic has evolved this time around?

Inextricably Ours is my ongoing struggle to figure out how to be in my position on this land. I live here, so I must figure out what is the best way to be. It's a complex situation because, you know, “best” for whom? In the series Perpetual Guest, I was coming to terms with the fact that I was indeed a settler. I was trying to understand what it means for me to live here as a settler and express how I feel about being a perpetual guest. After that work, I realized that there was a problem of simply acknowledging one’s position as a perpetual guest because guests have limited responsibility, which can lead to exploitation. I started to question the dynamic of guest and host and I started drawing the series Hôte. While thinking through and drawing about the complexity of positions of host and guest, I fell upon this word hôte which in French can mean both guest and host. I am cautious and unsure if I can even merge these two words as a guest here, but I also know that I can be a guest and/or a host in different places and situations. For example, I was recently guest hosting my parents when they visited me in Berlin, since I live there but I’m not really from there. It's a complicated dynamic and for me, it's not something that is set or settled. I wanted to think through this kind of complexity with Hôte. When I finished the 42 drawings and made them into an artist's book, I thought I was done investigating this idea.

Shortly thereafter, I was talking to an art theorist friend of mine En Jun Lee, about the resolve that I was hoping to have come to, and she suggested that there was more for me to process. She was right. I started to think and read more, and that’s when I fell upon the novella Flatland. Inextricably Ours is still thinking through this relationship between host, guest and land. Is it a hierarchical relationship? Can the same shape be perceived differently, as something else, depending on where one is? I trust the process of painting will give me answers to my questions. While painting, I think through the idea of one being seen or perceived as something different, while being the same.

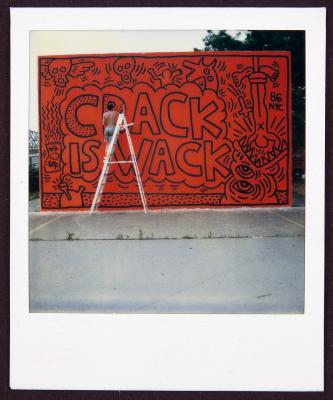

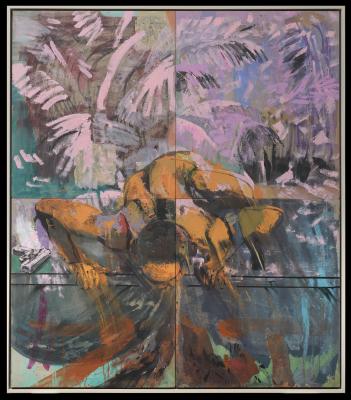

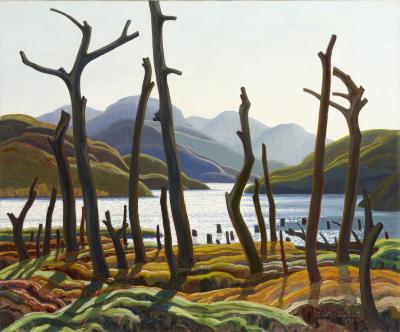

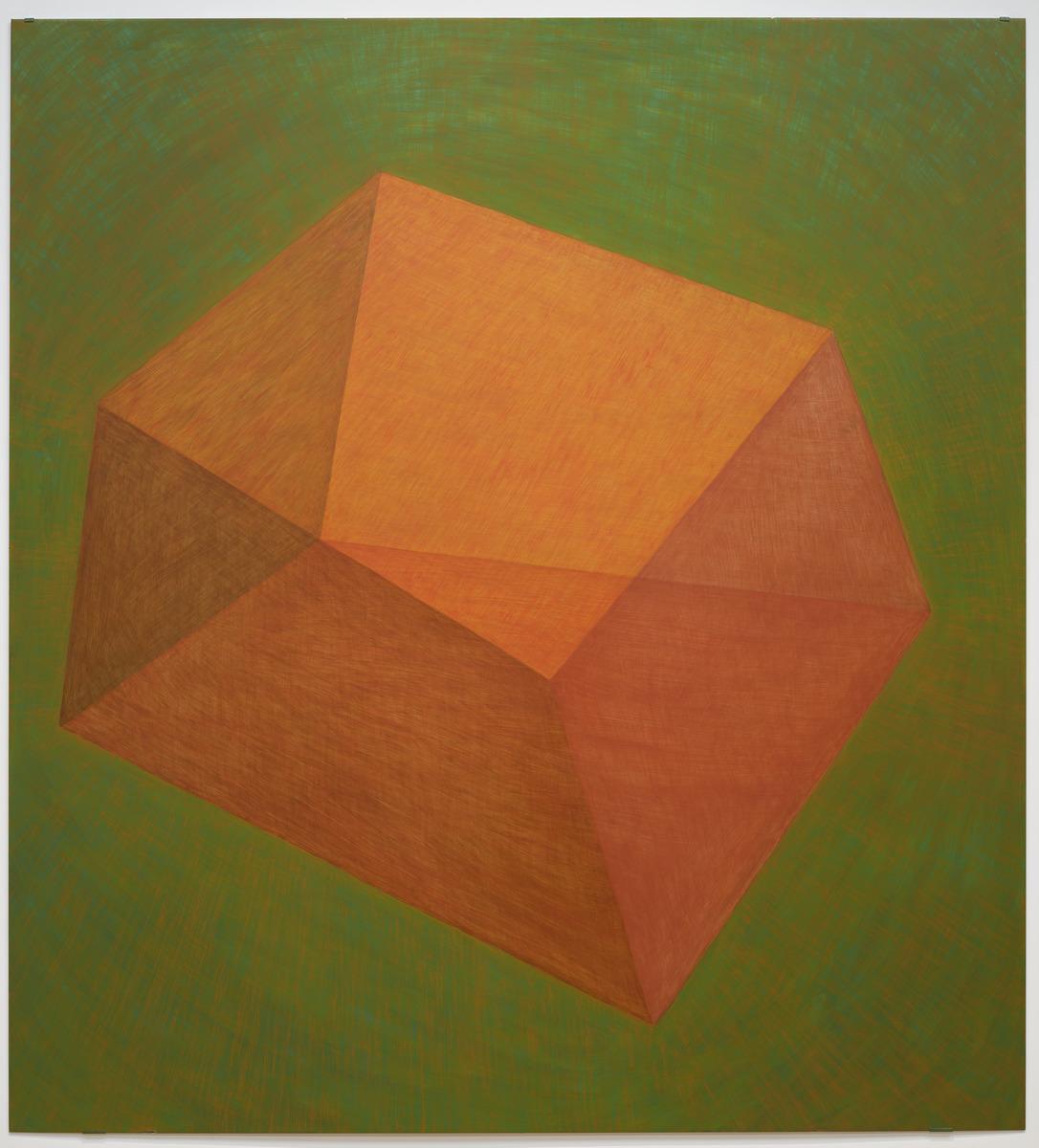

Jinny Yu. Inextricably Ours 23-08, 2023. Oil on aluminum, 152.4 × 139.7 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Jinny Yu. Photo: Rémi Thériault

Can you talk about your relationship to the Edwin Abbott’s novella Flatland: A Romance with Many Dimensions? When did you first encounter it? How and when did it end up becoming foundational to this series of work?

There was a period during the pandemic, for about a year, when I was mostly reading in my studio. I had the book [Flatland] around as I had heard about it a few years prior. It was only then that it piqued my curiosity. During my binge reading periods, I pick up the books that I have been meaning to read, and this was one of them. It’s a novella published in 1884 by Abbott, a schoolmaster and theologian, commenting on the class system in England in a satirical way, through shapes. He describes different dimensions of the world: the first dimension with dots, the second with lines and two-dimensional shapes, the third with three-dimensional shapes. It’s also about the impossibility of communicating between these dimensions. So, a shape from a three-dimensional space comes to the second dimension, and tries to explain what a sphere is, to a circle. It's impossible for the circle to understand and vice versa. Essentially, it's about the impossibility of understanding, if it's not your world.

I was thinking about how this is applicable in my world, 140 years later. And shapes fascinate me – telling stories about the world through shapes. Then somehow, these wonky cuboid seeped into my sketches. I was freely drawing and these shapes just came in, without any resistance or forethought. I started to draw these irregular cuboids and then it went on from there.

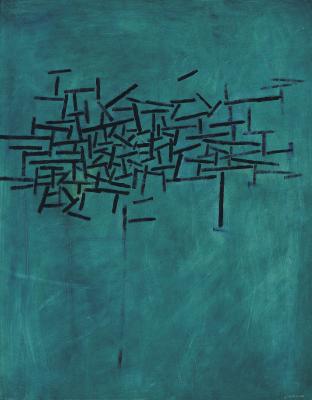

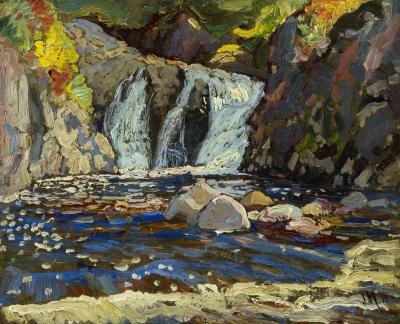

Jinny Yu. Inextricably Ours 22-01, 2022. oil on aluminum, Overall: 152.4 × 139.7 cm (60 × 55 in.) Courtesy of the artist.

There is an elusive, almost disorienting, element to these works, especially when one attempts to identify what shapes they may or may not be looking at. Is this an experience you intended viewers to have? If yes, how do you understand this experience in relation to the meaning of the work?

In Inextricably Ours, I'm thinking about rebelling against the regular shapes and regular standards that we all seem to accept. Nothing [in the series] is 90 degrees. And even the ones that are 90 degrees, depending on the point of view, are not 90 degrees. If 90 degrees in three-dimensional space is translated it into a two-dimensional shape, it's not 90 degrees. It's an illusion. So then, in a sense, the regular way of seeing the world falls apart. I wanted to think about that and exaggerate the instability, unsettledness and subjectivity of view – like viewing it from your perspective, and from my perspective, if we are looking at the same thing. If we flatten it, that two-dimensional shape would have different angles for each of us, even when it remains the same. So then how do we deal with this subjectivity? While thinking through this complexity and acknowledging subjectivity, I do think we have to get to some kind of common understanding. Yet I’m not sure how we get there because I think subjectivity is also very important.

With these works, I’m trying to understand where I could go from here. I use my paintings as a thinking tool. It’s a good tool for me to understand the world I live in. I paint to find an answer, and I end up with more questions. I am a romantic and an idealist, so I still hope for a better world – and I think we can find it but, sometimes I find myself in despair. I think, at the base, I am hoping for a reality in which everyone is happy – but then of course, reality is much more complicated. I think through my painting, I try to find some way of dealing with it.

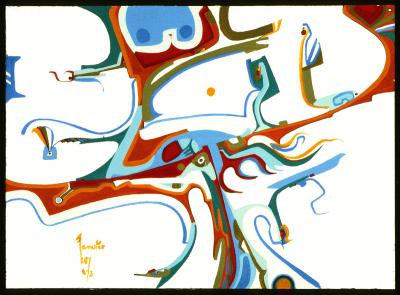

Jinny Yu. Inextricably Ours G23-02, 2023. Gouache on paper, 54.5 × 50 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Jinny Yu. Photo: Aylin Abbasi

You started work on Inextrcably Ours in 2021, but it is an open-ended, ongoing series. Can you share some of your thoughts about the potential future direction of the series? Are there any shifts, developments, or new explorations that you imagine for future works?

So far, there have been three phases of this series. I started with a closed shape on a field, then it started to open up, and now it's very open. [In Inextricably Ours] there are some works that are almost non-shapes, because they’re so open. I take it one painting at a time. Normally while completing one painting, I get the next idea. It’s usually an attempt to tackle a similar idea in a different way. Then I go on and on like this. Sometimes, through conversations with colleagues or friends or reading or perceiving the world, my process will open, and I start asking new questions. But still the works happen one by one, so I cannot predict what will happen. I do feel however, that I'm not even halfway through this series, because I want to somehow find this “answer.” I feel I'm still quite far from it.

Jinny Yu: at once is on view now on Level 2 of the AGO, in the J.S. McLean Centre for Indigenous + Canadian Art in the Irving & Sylvia Ungerman and Jennings Young galleries (galleries 230 and 231). This exhibition is curated by Georgiana Uhlyarik, Fredrik S. Eaton Curator of Canadian Art, AGO. In tandem with the exhibition, Goose Lane Editions will publish a bilingual 120-page monographic catalogue featuring essays by Patrick Flores, Ming Tiampo and Uhlyarik, and a foreword by Marie-Eve Beaupré. The publication will launch on September 14, 2024, with a roundtable conversation between Shohini Ghose, a quantum physicist, Yu and Uhlyarik.

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)