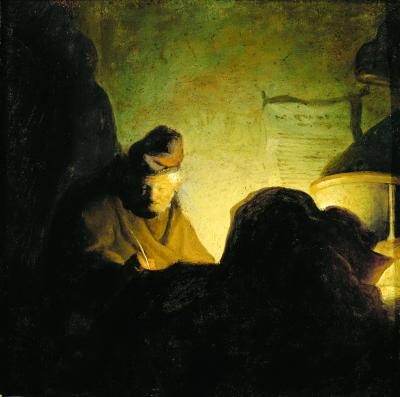

Portrait of a Young Girl with Carnations

Celebrate the arrival of spring with this sensitive portrait of youthful promise and flora

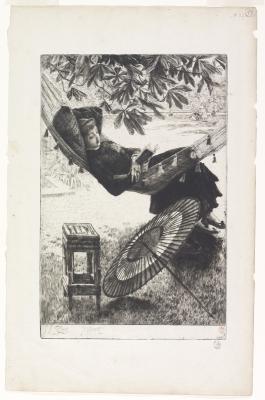

Jan Albertsz. Rotius. Portrait of a Young Girl with Carnations, c. 1663. Oil on canvas, 118.1 x 96.5 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of Miss L. Aileen Larkin, 1945. Photo © AGO. 2804

“The fairest flowers o’ the season, are our carnations,” Perdita, The Winter’s Tale, Act IV, Sc. III

One of the first flowers of spring, the carnation, has been cultivated, deified, and rhapsodized for centuries. Some credit the Greek botanist Theophrastus for its scientific name: dianthus, a combination of the Greek words dios, which means divine and anthos, the word for flower. Others believe the word carnation derives from the Latin word corona-ae, meaning a "wreath, garland, chaplet, crown," a reference to its use in Greek and Roman ceremonial crowns. In Tudor England, it had many names, including sops-in-wine, and uses both medicinal and epicurean. The official flower of Spain and the state of Ohio, it has variously symbolized womanhood, purity, motherhood, resistance and, when tinted green, homosexuality.

Around 1663, when Dutch artist Jan Albertsz. Rotius undertook this sensitive portrait of a four-year-old child (the picture is inscribed on the back “aetatis 4”, an indicator of age), the pink carnation was a widely understood symbol of blossoming love. The late Dr. Francis Broun, formerly of the AGO, suggested in the 1980s that it was used in portraits to signify betrothal. By way of proof, he directs our attention to the little girl’s left hand – her little finger is crooked to show off a ring while she gracefully plucks a flower by the stem.

The identity of the decorative figurine standing in the potted carnations is contested – Dr. Broun believed her to be Abundantia, the Roman goddess of abundance and fruitfulness. Others – the AGO’s Associate Curator of European Art Adam Harris Levine among them - suggest this figure is instead an homage to the Roman goddess Flora, heralding the coming of spring and rebirth. “Flora is typically depicted in art as a young woman with long flowing hair, usually holding flowers or a cornucopia,” he explains. “We see that in many places; in Botticelli’s painting Primavera and here again in the Rotius.”

Sumptuously dressed, draped in transparent Flemish lace, the identity of the little girl and her fate remains a mystery. Like spring itself, the portrait serves as a prelude to future events - her expression is composed, her fan is closed and the peacock, a Roman symbol of marriage, stands silently behind her. Barely visible in the distance is a small white church.

We have only a bare biography about Rotius – a contemporary of Frans Hals. Born in 1624, some speculate he was a pupil of Pieter Lastman, Rembrandt’s teacher in Amsterdam. He married and moved to the waterside town of Hoorn in 1643 and had seven children, one of whom, Jacob, would become a noted painter of flowers. Rotius died in 1666. While the work demonstrates no striking artistic personality, it is exemplary in its technique – the highly detailed dress and jewels, the transparent lace, the wistful expression, and the polished shoe, all set off against a loosely painted background. According to Levine, “though little is known of Rotius and his life, the quality of this painting makes clear he was an extraordinarily gifted portrait painter.”

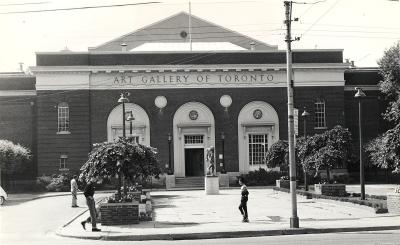

This month's RBC Art Pick is Jan Albertsz. Rotius’s Portrait of a Young Girl with Carnations, c. 1663. The painting is currently on view on Level 1 of the AGO in the Tanenbaum Centre for European Art (gallery 119).