Ask Aunt Easel: fur-give or forget

Aunt Easel answers your most pressing questions with grace, humour and a little art history.

Henry Fuseli. Lear Banishing Cordelia, c. 1784-1790. Oil on canvas. Overall: 267.3 x 364.5 cm. Gift from the Contributing Members' Fund, 1965. © Art Gallery of Ontario

Our gilded Aunt Easel, the Foyer’s intrepid advice columnist, is back with even more humourous and unhinged insights, all ripped straight from the art history books. Have a question? Need some artistic comfort? Send your questions to Aunt Easel at [email protected]

Dear Aunt Easel,

My Zoomer parents would be so much happier with a pet, but keep citing the usual excuses – effort, expense and damage to furniture. Instead, they continue to focus all their attention on me and my stalled career/personal safety/hypothetical future children. “We’ll be trapped!” they say. “Vet bills are extortion,” they say. “Dogs don’t call you on your birthday,” they say. Ridiculous, I say. Can I just adopt a dog and leave it in their spacious suburban backyard? We would all be so much happier.

Signed,

Fur-give or forget

Dearest Fof,

Pet adoption is such an admirable undertaking! But gifting animals can be a terrible thing! I’m afraid the best you can do is launch an influencer campaign…sign them up for the Humane Society newsletter, bark into their dreams, and leave copies of Marley & Me in the vegetable crisper. In the long run, that dog, cat or parakeet are only temporary (albeit adorable) fixes for their overbearing behaviour.

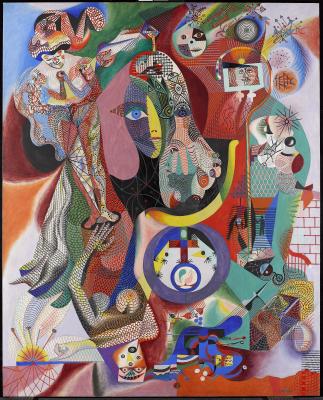

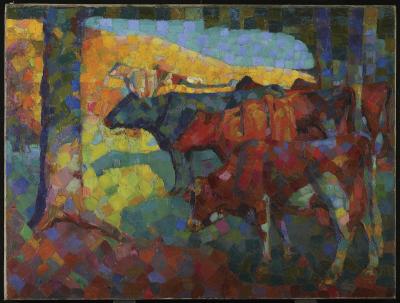

Not convinced? Consider Swiss-born British artist Henry Fuseli’s massive painting Lear Banishing Cordelia (c. 1786-89) [image at top]. Illustrating the opening scene from Shakespeare’s unbearably sad and tedious play King Lear, Fuseli captures one of western literature's great moments of family dysfunction. A furious and wild-eyed King Lear is shown disinheriting his youngest daughter Cordelia for not matching her sister’s overt (and ultimately false) assertions of love. With its grand scale, exaggerated gestures and theatrical spotlighting, Fuseli — an artist who changed his last name to sound more Italian — has no interest in trying to make this scene look natural. If anything, he’s intensifying the dramatic action, safe in the knowledge that his audience already knows how the story ends and can’t be shocked by what they are seeing. Eighteenth-century London knew full well that Cordelia, after attempting to teach her father a lesson in credulity, will suffer greatly.

My point? No one likes being manipulated. And big gestures are best reserved for people who know what's coming. So be like Fuseli, chase fame and fortune and the affections of Mary Wollstonecraft , even change your name – but leave the high stakes drama on the wall.

Dear Aunt Easel,

Over the past months I have acquired a little more avoirdupois than I would like. Cooking is entertainment! While I am working hard to transform the silhouette, I need some exciting, vibrant, yet concealing clothing for my re-entry into the world. Can you help?

I’ll be happy to give you credit when the compliments arrive.

Yours truly,

Loving Pandemic Eating in Kingston

Dearest LPEK,

I know the feeling. I have been clothed in a giant napkin for the past eight months, hoping its limp folds might lend me a certain Grecian appearance. Alas, the reality is more Mount St. Helens than Helen of Troy. But we’re both being ridiculous. What really matters this summer is the health of our families and communities, and the only thing people will actually think when they see you is how nice it is to see anyone again.

But seeing as you asked, my advice is a new hat. Why? Because millinery is too powerful an art form to be held hostage by horsey royalty. “A man of many hats” isn’t an idiom for nothing; but a genuine statement of fact, literally and figuratively.

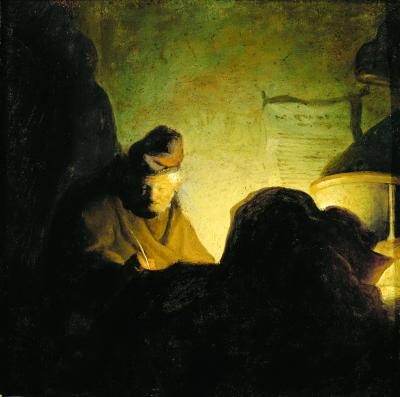

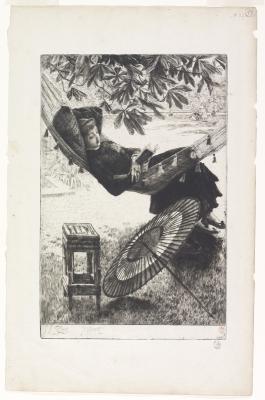

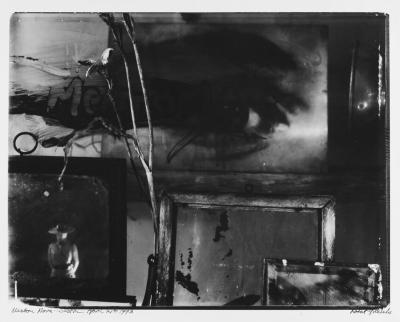

James Tissot. The Rubens Hat, 1875. Etching on laid paper, Image: 25.4 x 16.2 cm. Gift of Allan and Sondra Gotlieb, 1994. © Art Gallery of Ontario 94/196

Just ask Jacques Tissot, that beloved painter of the ‘polite classes’. He juggled commercial and artistic success, a mistress or two, and big religious feelings, likely all while wearing different hats. Besides, hats made him very wealthy. Of course, he did bags and dresses and shoes very well, with all sorts of hidden messages about sex and money hidden in their ruffles. But I think hats are his strong suit. This elegant mezzotint from 1875 is a piece of showmanship existing solely to demonstrate his alacrity with headgear. And why not bring back the Rubens hat? Popular in London society between 1865 and 1890, it appears to be a long bread basket with a jaunty upturned brim on one side, ideal for social distancing. Likely named after a Rubens painting in the National Gallery of London, it does bear a strong likeness to the popular Gainsborough hat of the previous century. Proving that you can make an old hat new again.

Will I, too, be wearing an oversized hat this summer? Yes, if I can find one to match my napkin.