A Q&A with Carmen Robertson

Ahead of her talk on March 19, art historian Carmen Robertson shares the first time she saw the art of Norval Morrisseau

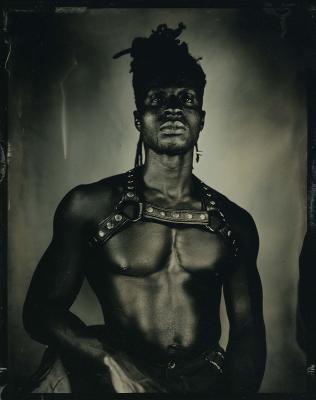

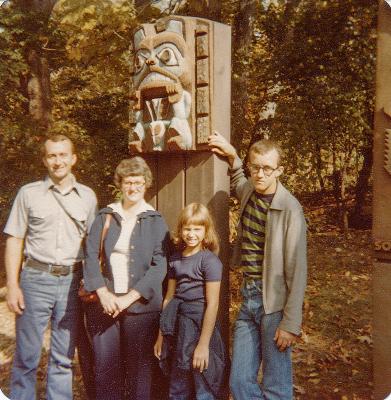

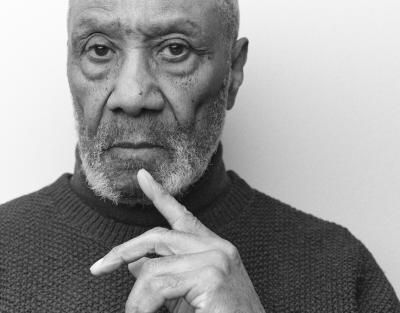

Image courtesy of Carmen Robertson

It was in the early 1980s that Carmen Robertson first encountered the work of Norval Morrisseau. “It was a game changer. What I saw in the window of the Imperial Oil building in downtown Calgary was an explosion of energy in the form of art. The colours just blew me away.”

“I grew up in small-town Saskatchewan, where really, we saw no art, and definitely no Indigenous art.

Today Robertson is an acclaimed author and art historian at Carleton University, spearheading with Ruth B. Phillips, The Morrisseau Project, 1955-1985. This multi-year research project is the first serious investigation into the first three decades of Anishinaabe artist Norval Morrisseau’s career, a major step towards the creation of his catalogue raisonné. Nearing the finish line, Robertson and the eleven-member research team look forward to publishing results in 2026.

This month, to celebrate Letendre/Morrisseau, a new installation of works by groundbreaking painters Rita Letendre (1928–2021) and Norval Morrisseau (1932–2007) from the AGO Collection, the museum welcomes Roberston for a conversation with Georgiana Uhlyarik, Fredrik S. Eaton, AGO Curator of Canadian Art.

Ahead of their conversation, we caught up with Robertson to learn more about Morrisseau’s relationship with Letendre, why his early years are so fascinating, and why is he so beloved in France.

Foyer: Seeing Letendre and Morrisseau’s paintings hung side by side is so exciting. What do we know about their relationship?

Robertson: I can only speculate but would be surprised if they had not met somewhere! That said, in the 1970s, Morrisseau spent a lot of time in Toronto, and so did Letendre. Well, even if they were never in the same room, it is clear that their energy and use of colour unite them!

Morrisseau is most often described as the leader of the Woodland School of Art. Is that accurate? Is there a visual style before or after that?

From the very beginning, in the late 1950s, Morrisseau played with how to conceptualize a visual storytelling language steeped in Anishinaabe ways of knowing. But it really took until the mid-1960s before he fully fleshed out the elements that we know as his visual vocabulary. He did not promote the Woodland style, he created it. It is very much his own creative use of line and colour. The subject matter, especially prior to 1975, is based on Anishinaabe stories and the many contemporary issues that influenced him.

What was the response from Anishinabek audiences to his work? During his ascendency, was his work being seen by both Indigenous and commercial art audiences?

There was a time, early on, that some community members were upset with him for painting what he did. This, I think, comes out of living in a colonial period where Christianity was being promoted heavily. To be seen creating art about traditional and sometimes sacred stories was upsetting to some. But very quickly, generations of Anishinaabe artists began to experiment with visually expressing their stories through the Woodland style that Morrisseau originated.

What was Morrisseau’s relationship to his Toronto art dealer Jack Pollock like? How significant was Pollack in making his art known?

Until fairly recently, many of stories that we knew about Morrisseau and Pollock’s (now deceased) relationship were mediated through Pollock’s writings. Known, famously, as the discoverer of Morrisseau, Pollock comes across as a heroic figure.

Correspondence in the Pollock archive donated to the AGO is where we see a clearer picture of the early struggles. We know now that Morrisseau was not, at least in the 1960s, happy with their relationship. Morrisseau’s letters to Pollock often ask for guidance, with the artist admitting his lack of understanding about the business-end of the art world. These letters undermine some the established altruism of Jack Pollock! It is exciting research that reveals the many complications of their early relationship. Between a dealer and an artist here is always an awkward economic reality that taints things. I do think though that Pollock went out of his way to make Morrisseau’s art a part of the conversation in the Toronto art scene and that it eventually led to them having a stronger relationship by the 1970s.

‘Picasso of the North’ is a phrase we often hear applied to Morrisseau. Do we know how he felt about the comparison?

I would guess that Morrisseau mostly liked the association with Picasso! During the earliest days of his formulation as an artist, near Red Lake, Ontario, in the late 1950s, he was introduced to Picasso’s work by Joseph and Esther Weinstein. The Weinsteins were both artists connected in the Parisian avant-garde art movement and to Picasso’s circle. The actual moniker, ‘Picasso of the North,’ if I remember correctly, stems from an early Weekender magazine article, but it stuck, and it became a great marketing tool. We know that when the Weinsteins left Ontario, Morrisseau gave them a small painting to present to Picasso on his behalf. Joseph Weinstein writes in his autobiography about how on the back of that painting, Morrisseau had written “from one great artist to another,” which is revealing about how Morrisseau saw himself as an artist!

The 2006 National Gallery of Canada retrospective is often credited with making Morrisseau a household name in Canada. Was there international recognition that came before that?

Oh absolutely. In 1969 Jack Pollock and Herbert T. Schwartz from Montreal organized an exhibition of Morrisseau’s art in Saint-Paul de Vence, in France and this was the start of a number of international exhibitions, but this was Morrisseau's first entry into the international art scene and to French patrons. Pollock organized another show in 1975 in Cannes, and significantly, he was also chosen to represent Canada as an Indigenous artist in 1989 for Magiciens de la Terre, at the Centre Georges Pompidou. This was a problematic exhibition for many reasons, but his inclusion is proof that French audiences embraced his work. I like to say that the French appreciated Morrisseau in the same way they appreciated Jerry Lewis, the comedian.

Should we be talking about Morrisseau as a queer artist?

There are strong reasons to talk about Morrisseau, especially from the mid-1970s on, as a Two Spirit or Indigiqueer artist. Métis curator and scholar Michelle McGeough has done research on this aspect of Morrisseau’s life, and she is writing a chapter for our book that will help to expand understandings. The Morrisseau Project has shifted thinking about the artist’s so-called erotic works and we relocate the discussion around love medicine. The term Love Medicine – with its expansive understanding of relational conjoining – I think makes more sense, and challenges us to rethink the complexities of many of Morrisseau’s works. On the website that we created with the MacKenzie Art Gallery (morrisseaustorylines.com) ,we include a section on his love medicine art, displaying several works that have never been seen publicly.

Don't miss Carmen Robertson and Georgiana Uhlyarik, Fredrik S. Eaton Curator of Canadian Art, AGO, in conversation about Rita Letendre and Norval Morrisseau, on Wednesday, March 19 at 7 pm in Baillie Court. Presented in conjunction with the exhibition Letendre/Morrisseau. For tickets and more information, visit ago.ca/events/morrisseau-and-letendre.