June Clark unravels the American flag

The Harlem-raised, Toronto-based artist reflects on her solo exhibition on view now at the AGO

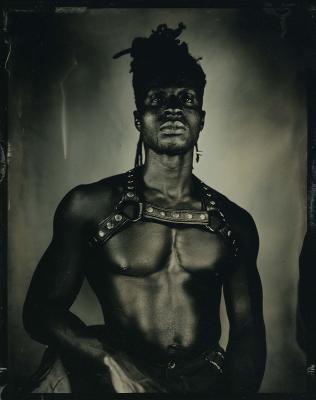

June Clark with her work, Moral Disengagement, 2014 - 2017. Polyester, wood and oxidized metal, Overall: 254 × 175.3 × 7.6 cm. The National Gallery of Canada Collection, Ottawa. © June Clark, courtesy of the artist and Daniel Faria Gallery. Photo: Craig Boyko © AGO.

The red, white, and blue. The stars and stripes. The American flag means many things to many people. For Toronto-based artist June Clark, the meaning of the flag has shifted throughout her life, a journey which began in childhood.

Clark was raised in Harlem, New York, in the 1940s and attended school there for eight years. For children like her, the message was clear – the flag was to be revered and respected.

But times do change. And as Clark got older, her feelings about the flag began to unravel.

To say that 1968 was a year of upheaval in US history would be an understatement. For Clark, it was the year that she and her then-husband left Harlem and landed in Toronto. In the decades that followed, she established herself as a renowned multidisciplinary artist whose work spans photography, installation, etchings, sculpture and collage. She has gone on to exhibit her work across Canada and internationally and holds an MFA degree in Visual Arts from York University. Throughout it all, the American flag remained consistent in her practice. She used art to come to terms with the flag and its broken promises, exploring it as both a symbol and material.

Spanning three decades and nine works that investigate the American flag, Unrequited Love is Clark’s second solo exhibition at the AGO, following her 2018 presentation and her inclusion in the 2016-2017 group exhibition Toronto: Tributes + Tributaries, 1971-1989. The 2024 AGO exhibition is on view on Level 2 of the AGO in the Murray Frum Gallery (gallery 249) and is presented in tandem with another exhibition of Clark’s work titled Witness at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery in Toronto which opens on May 3, 2024. Unrequited Love was first shown at Daniel Faria Gallery in 2020, and Clark dedicates the exhibition to Colin Rand Kaepernick, the football quarterback who knelt during the national anthem in 2016 to call attention to the continued violence towards and oppression of Black people in America and around the world. Unrequited Love at the AGO is curated by Julie Crooks, AGO Curator, Arts of Global Africa and the Diaspora.

Days before Unrequited Love opened, Clark spoke to Foyer, shedding light on how she began exploring the American flag in her practice, growing up in Harlem, and what 2024 has in store.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Foyer: It feels like 2024 will be a stellar year for your art. You’ll have this exhibition at the AGO, another solo exhibition at the Powerplant, and another group exhibition at MOCA. How are you feeling about it all?

Clark: I mean, I'm just excited, and I'm very grateful. It feels nice. It feels lovely.

Is it nice to be recognized, especially in your community here in Toronto as well?

Yes, and I have been over the years, but certainly not as concentrated as is going on now. And for that, I have to thank Daniel Faria. Well, first it was Wanda [Nanibush], with [the 2016-2017 exhibition] Tributes and Tributaries. I felt when she called me in 2017, she was reaching way back in the cupboard, pulling me out to the front. That was very nice. And then through her and lunchtime Zooms, Daniel saw the work and he saw the exhibition. It's been a whirlwind since I met him.

June Clark, Inherent, 2017. Acrylic on canvas, Overall: 94 × 157.5 cm. Private Collection, Toronto. © June Clark, courtesy of the artist and Daniel Faria Gallery. Photo: LF Documentation

Speaking of Daniel, Unrequited Love [at Daniel Faria Gallery] was the first time all these works were shown together. As you're preparing to show them again, this time in a different space, is there something different that has been revealed to you seeing them here?

Not yet. I mean, it's not quite up yet. So, it will be nice once it's done to have a look, but right now, not really. I'm very pleased that Julie [Crooks] wanted to add Tubman , the yarn piece with the chains, to the exhibition, and rightly so. She feels that it's all a part of the same thinking having gone into the work. When they were first shown together, I was quite surprised, because as I say, I didn't realize I was doing them. If I had downtime in the studio, or if there was an installation I was working on, there was always a flag that emerged. When I began Moral Disengagement, which took me about three or four years to do, it was made the same way that one knits or something. I just began pulling threads on the flag. As I'm sitting there pulling threads, I looked around the studio, and there are all these flags that I've done. And I was saying to someone yesterday, one of them is so old I signed it with my first husband's last name [laughs]. It's been 30 years.

June Clark, Moral Disengagement, 2014 - 2017. Polyester, wood and oxidized metal, Overall: 254 × 175.3 × 7.6 cm. The National Gallery of Canada Collection, Ottawa. © June Clark, courtesy of the artist and Daniel Faria Gallery. Photo: LF Documentation

Amazing. You've described that it took you a long time to understand that the flag isn't evil, but it's a symbol which you were taught to invest your emotions. Can you describe that sentiment further?

Well, from five years old until you are 17 and graduating from high school, in the morning, you enter the classroom, and you have to stand with your hand over your heart and pledge allegiance to the flag. And when someone does that from, when they were five, that's their thinking, that "yes, this is an amazing thing, and it represents all that good stuff about where I live". And slowly you begin to think and realize, wait a minute, wait a minute. That's what My Precious is about with the flag with 48 stars, because at that time, there were only 48 states. And August 28, 1955, that's when Emmett Till was killed. He was exactly my age. That's when you sit up and take notice as a teenager and you think "this is my cohort." The milk starts curdling.

June Clark, My Precious 1946 - 28 August 1955, 2017. Cotton, velvet, glass, wood, Overall: 89.7 × 71.9 × 54.1 cm. Courtesy of the Artist and Daniel Faria Gallery. © June Clark. Photo: LF Documentation

Would you say then that each of the works represents a different emotion that you feel towards the flag?

No, [From Harlem] is just coming to terms with how I felt at the time [when I made it] in Harlem in 1997. I was at the Studio Museum, and they asked me to mount a small exhibition for Martin Luther King Day. That's where the idea for that image came from because I was living in Harlem again, and coming to terms with, and I hate to say, broken promises. And then Dirge (2003) was when I felt everything was truly falling apart, the neglect of the country, all of those things. And, Alas... (2006), with the wine and tea, that was when I was in Paris, and I guess I feel that probably for me, is the most poignant of the pieces. I did a whole series of paintings with wine and tea, because that's what one has in Paris. And Untitled (irony) (2010), I also did in Paris.

So, it's more about the periods in your life?

Yes. And how I was feeling and again, whatever studio I was in. I can pretty much say where I did each and every piece and what I was feeling at the time. And I think my titles say just that.

Artists have often disassembled or deconstructed a symbol to undermine or subvert it, presenting a new narrative. Is that applicable to your work?

No, no, not at all. First of all, not one of those works was ever made with anger or anything like that. They were all me trying to come to terms with, like a lover, trying to come to terms with why and how I've been betrayed. And as I say, it's like when you were a little kid. When you get a gift or something often, and I saw my son do this, you'll take it apart to see how it works, why it works, what's in there, what's fascinating about. I think that was the impetus to do these pieces.

You’ve explained it already, but I'm always interested in the practical details about how artists make their work. I understand you’re always looking for materials to work with and find a lot of inspiration in materials that have been discarded or abandoned. You’ve described how you find rust to be interesting like in Dirge. Can you tell us more about what went into your process of making each of these works on view?

Well, often, I have an idea of what I want to say. And then I find materials in which to say them. That's why a lot of my work is eclectic in terms of media and materials. Because, again, I have the idea and then try to figure out how best to visually illustrate it.

June Clark, Dirge, 2003. Oxidized metal on canvas, Overall: 94 × 160 × 1.8 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Purchase, with funds by exchange, and funds from Joyce and Fred Zemans, 2021. © June Clark, courtesy of the artistand Daniel Faria Gallery. Photo: LF Documentation

Travelling through the US, the American flag is everywhere and it's very much an outward expression of patriotism, whereas in Canada, we don't have that as much. We're much more reserved about it.

Well, it's true as, Terrence, my husband who is from Saskatchewan says, the maple tree doesn't even grow in half the provinces! But, again, if you're indoctrinated from age five, you’ll have these kids, and they’ll all believe in the flag.

So, did that stand out to you when you came to Toronto in the late 1960s?

I came to Toronto in '68. And I have to say, I was with my then husband and we went to see a film for the first time here in Canada. Before the film played, they played the [Canadian] national anthem and I refused to stand up. That was rude because it was a completely different context. I'm sorry I did that. If I had done that à la Colin Kaepernick in the States and I probably would have gotten beaten up. That's the difference. I mean, you don't hang every hope on a symbol here. That's healthy.

Speaking of Colin, when you first showed Unrequited Love at the Daniel Faria Gallery, you dedicated it to him. And, of course, there have been several instances throughout history where Black athletes in particular have intersected with politics, civil rights and racial inequality.

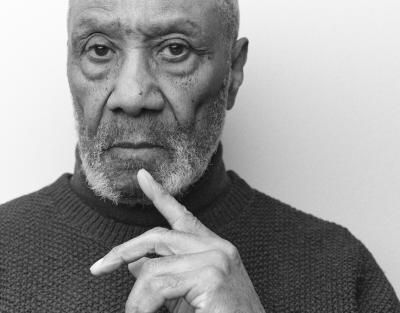

Well, how can they not? I think as much as they can. I think Colin Kaepernick has pointed out that this is like modern-day slavery with these athletes. We've seen it with gymnasts, and the swimmers and the bicyclists, the baseball players. I mean, it's all the same. It's as if these people are living on a plantation and it's very difficult because of the carrot of millions of dollars. I mean, look at the strength of what this man has done and what it has cost him career wise. It's disgusting. That there are so many people who could, who are in positions of power, who could say, "give this man a break". But no one has said that and that's horrible because no one wants to mess with their bottom line. Even the multibillionaires who could just sit back for the rest of their lives and do nothing are saying nothing. And that is the crime. When you're a witness, and you don't open your mouth.

To this day, Colin is still struggling.

Still going through it and not getting any help from people who could easily step in and help.

We're going into an election year in the US and several countries worldwide. Do you have any thoughts about that in relation to this work and how people may perceive it?

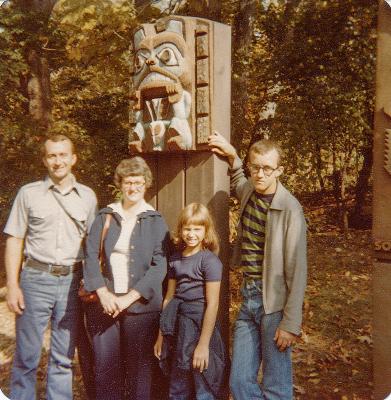

As I say, none of this work was done in anger but the anger worldwide is palpable right now. For so many reasons. For broken dreams, for all of these things. People feeling that they're owed, and they want theirs, they want to be like a celebrity or whoever they feel, they just want theirs. And I didn't grow up that way. I wasn't taught that. I mean, you can see from the images that Julie put up of my family and whatnot, we just got on with it. I didn't aspire to be rich or famous, or any of those things. I aspired to be a good person, a contributing person, etc. And I just think that right now, and no one's taking responsibility for themselves. Whatever happens is someone else's fault. And no one owns what they do anymore.

June Clark, Tubman (from the Perseverance Suite), 2023. Metal, yarn, paint, Overall: 241.3 × 228.6 × 25.4 cm. JK Brown & Eric Diefenbach, New York. © June Clark, courtesy of the artist and Daniel Faria Gallery. Photo: Dean Tomlinson

June Clark: Unrequited Love is on view now on Level 2 of the AGO in the Murray Frum Gallery (249). The exhibition is curated by Julie Crooks, AGO Curator, Arts of Global Africa and the Diaspora.

June Clark: Witness is on view at The Power Plant Contemporary Art Gallery through August 11, 2024.