A Q&A with Annabelle Selldorf, Principal, Selldorf Architects

In this continuing series, we introduce the team behind the Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery.

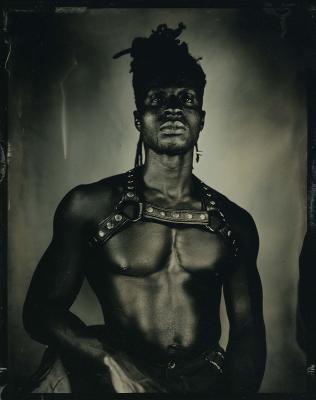

Annabelle Selldorf. Photo by Stephen Kent Johnson. Courtesy of Selldorf Architects.

For more than a decade, Selldorf Architects has been synonymous with luminous museum design, having given shape and texture to Luma Arles, the National Gallery London, the Frick Collection and the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, among many others.

And yet, in discussion with Annabelle Selldorf, founder and Principal at the globally celebrated 70-person New York City-based firm, what comes across most strongly — in tones as open, as inviting and thoughtful as her designs — is not the scale of these achievements or even their singularity, but her enjoyment of the process, of the work.

One of three architects propelling the design of the AGO’s Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery, Annabelle’s vision of a beautiful and highly functional space, crafted through collaboration, continues to inform everything from building materials to ceiling heights. In this second installment of our ongoing series highlighting the people whose creativity and passion are making the AGO’s Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery expansion project a reality, we spoke with Annabelle about how she came to the field, her inspirations and how architecture is always the product of collective action.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Foyer: How did you come to architecture?

Annabelle: In some ways, one might say that it was inevitable because my father was an architect, and it was the family business. In other ways, the opposite is true. My father always worked so hard, and yet money was very tight. His experience of architecture as a service business made me really uncomfortable. As a teenager, I had decided against it, but eventually I applied to architecture school in New York City. I was fortunate to work in an architectural office throughout school, and literally from the moment that I began working, I never questioned my decision again. In retrospect, of course, it feels like I was nicely prepared. Albeit with all the hesitation and all the doubt that comes with choosing any profession.

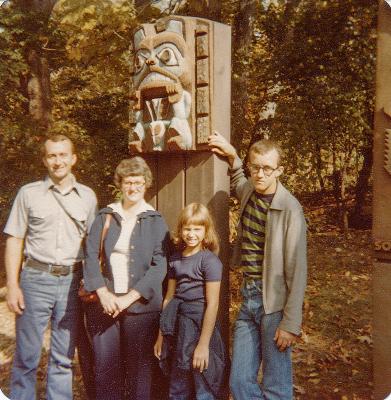

Annabelle Selldorf in the offices of Selldorf Architects, NYC. Photo by Nicholas Venezia. Courtesy Selldorf Architects.

You’re a celebrated leader in your field. Did you always want your own firm?

I've been lucky to build an office of 70 people — many of whom have been here for a very long time — but that wasn’t overnight and it certainly wasn’t by myself. Nobody does anything alone. Perhaps I'm the standard bearer, a sheepdog that rallies everyone together - but everyone contributes, and the firm exists through collaboration. My instinct after school was to work for myself - it felt natural. There was a time when there were just three of us. Then, one by one, people came aboard, and it went from having some projects to having a firm. Suddenly, there were office hours, and we had an accountant. It was both natural and unexpected.

Do you feel that there is a glass ceiling for women in architecture?

I’m often asked this question. I don’t think there is a glass ceiling per se, but the reality of the many barriers that keep women from professional success in all fields — financial, childcare, societal biases – have to be acknowledged. Anything that keeps half of the population from success needs to be addressed. There was a time when our firm was largely female, it seemed that only women were applying, but it is more evenly split now. I am very proud of our firm culture and feel that it provides a nice work/life balance that allows everyone to succeed equally.

What is the most satisfying part of the design process for you? Is it seeing the finished product, the creative dialogue or the problem solving?

It's really all of it. In the best of worlds, you are excited to work on a project because of the client and the environment and the type of building, and the satisfaction comes when you really understand the project. That never happens alone - you do that with your colleagues.

Convincing others of your design strategy is a big part of any project, and that’s where you can feel a bit like a boastful parent, talking about your exceptional, beautiful child. Those feelings sit side by side with the internal critique, the thoughts of how you might have improved or might have thought about something differently.

A description commonly applied to your work is ‘stealth architecture.’ Do you think that’s accurate? What do you think people are responding to when they say that?

I’ll admit I think of myself as somebody who is slow and measured and careful with the kinds of interventions I propose, to the point that I've even wondered if what I do is boring, or bordering on, nothing. So while it’s not my word, I think it’s okay, because it recognizes that we made decisions with intention and that is very accurate.

The language of architecture is interesting. There’s certainly no precision in the way the media talks about architecture. When people describe clean lines, I wonder, what's a dirty line? Is it dusty? If what we do is supposedly stealth, what is it’s opposite? Big stealth?

Do you have a favourite building?

My favourite in the world? The Pantheon in Rome, maybe. It’s one of the most welcoming buildings I can think of. It’s magic - a civic building, whose materiality is so present. I was there recently, and we just stood inside it, talking about it, all day long.

As far as my own buildings are concerned, they are all old friends. While it’s lovely to visit a home you had a hand in designing, even after 30 years of practice, my favourite building is always the one I’m working on now. You have to really love what you are doing in the moment in order to fully engage, and you have to find ways to nurture and sustain that enthusiasm.

Where do you go for visual inspiration?

No one place. I am somebody who has deep visual memories, a sort of library inside my head, and I rely on that a great deal. Often, I will see something, and it will occupy my mind, and I trust that it will surface when it wants to be realized. I find it interesting how much inspiration is derived from bringing a memory into a new setting or context.

In the work our office does, we want to have reasons to do something. That means that design decisions are the result of a cast of characters working in concert - space, program, site, budget. In this drama, inspiration is more of a supporting character. It's the complex layering of different thoughts and ideas in one building that creates the rich texture we’re after.

Stay tuned for more exciting insights and updates as the AGO anticipates breaking ground on the Dani Reiss Modern and Contemporary Gallery, its expansion to increase space for the AGO’s collection of modern and contemporary art.