Textiles as Reclamation with Norwin Anne and Carol Ann Apilado

The artists reflect on working with textiles, Pacita Abad, and their journeys to cultural reclamation

Norwin Anne weaving on a handmade loom at the Samahan sa Basahan workshop for the KAMI Program with Kapisanan, 2022. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Textiles - we use them daily, whether it’s to clothe our bodies or make our homes cozy. However, our everyday use of textiles goes beyond utility. We use them to express ourselves and signal certain aspects of our identities. And for many, textiles are a way to reconnect with their cultures.

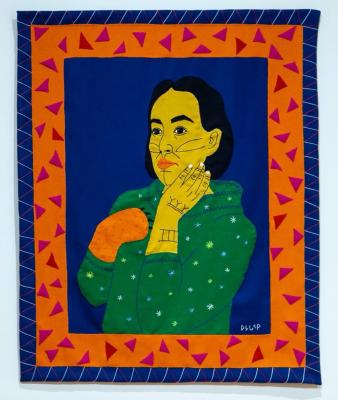

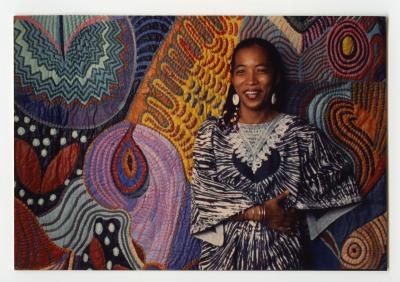

For Ilokano weaver Carol Ann Apilado and multi-disciplinary artist, (re)maker, and eco-culture communicator Norwin Anne, working with textiles has become a site for cultural reclamation. As part of programming for the exhibition Pacita Abad, now on view at the AGO, the pair will share this practice during their free workshop Textile Art as Reclamation: with Norwin Anne and Carol Ann Apilado, happening on Wednesday, November 6 at 4 pm.

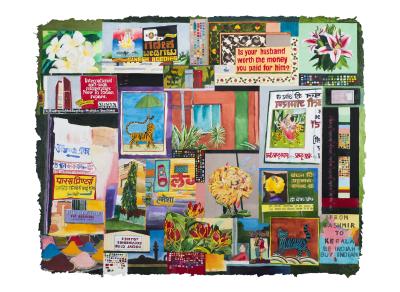

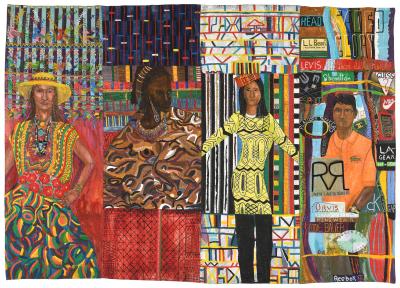

Although Pacita Abad (1946 - 2004) was not a weaver, she was an avid collector of global textiles which was one of the ways she authentically engaged with the communities she encountered during her travels. She used these materials to create trapuntos - large, vibrant textile collages that highlight the cultural significance of textiles and reference the history of textiles as art.

Carol Ann Apilado, Ilokano Weaver. Photo by Francis Pratt.

Inspired by Abad’s love of textiles, Apilado and Anne’s workshop will highlight the cultural significance of weaving, as well as encourage participants to think about textile creation with a slow, conscious mindset. Apilado will teach weaving the traditional Ilokano pattern Kusikus on a table loom while Anne will teach participants the basahan weaving technique, which uses a handmade loom and fabric scraps to create a new textile. Anne will also be hosting additional weaving and screen-printing workshops at the AGO throughout the month of November and early December.

Ahead of their workshop, Foyer caught up with Anne and Apilado to learn more about how their artistic practice incorporates textiles and their reactions to Pacita Abad as Filipinx artists.

Norwin Anne, multi-disciplinary artist, (re)maker, and eco-culture communicator. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Foyer: How did you first come to weaving and working with textiles?

Apilado: I grew up seeing and being around Ilokano inabel (textiles) my whole life. To be honest, I didn't think anything of it and thought it was a common and normal thing for Filipinx diaspora to have these handwoven blankets from the Philippines. It wasn't until 2018 that I really understood how significant and deeply rooted the traditional craft was in my family. That was the year my papa was shocked I was suddenly so interested in Filipino textiles. He nonchalantly asked me if I knew that my Lola (grandmother) came from a family of weavers in Bangar, a weaving town in La Union, Philippines, well-known for their handwoven blankets. Learning about our family's connection to an ancient craft back home was the beginning of my weaving journey.

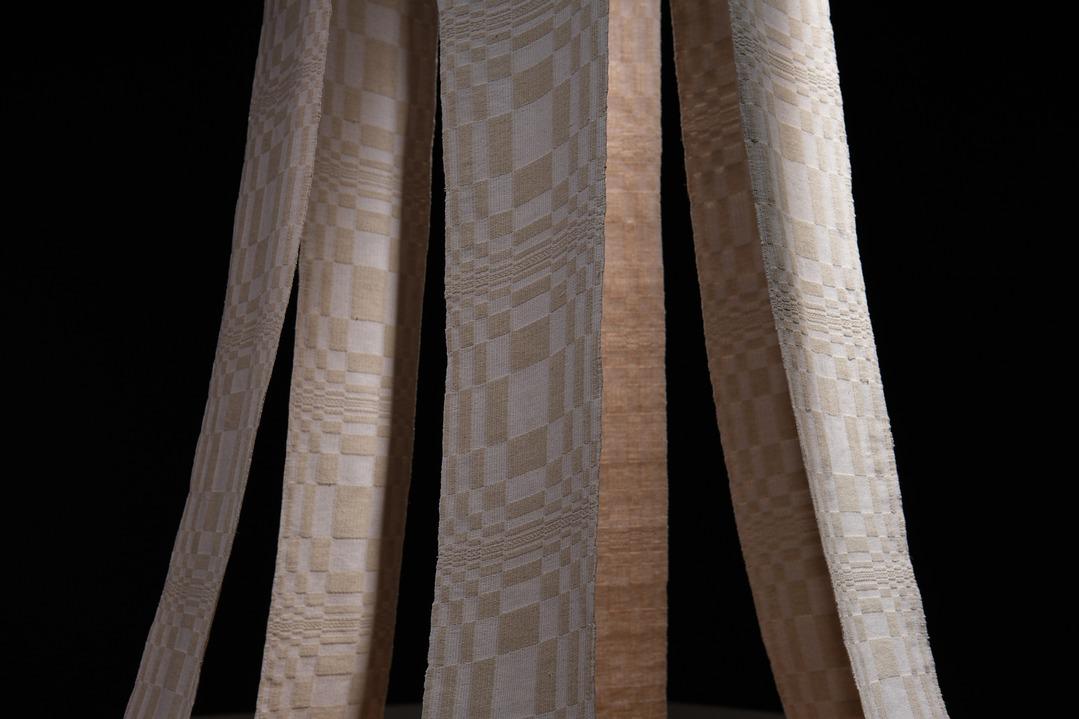

Carol Ann Apilado, Channel, 2023, cotton and cottolin (cotton/ linen), stones, and pillow, approximately 4' diameter, 12' high. Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid.

Anne: I’m a very waste-conscious person. When I studied Fashion Techniques and Design at George Brown College, I became more aware of textile waste from the fashion industry and its social and environmental impacts. As an artist, I always prioritize working with used and found materials, mostly clothing and textiles. Throughout the years, I collected a lot of my own “textile waste,” and also from the community clothing swap and repair program I started in 2022 called From Here to Wear. The purpose is to create a closed-loop system for local “textile waste,” diverting it from landfills by facilitating sewing and creative mending workshops to extend the life of clothes. I also started experimenting with different ways to repurpose clothes beyond repair by deconstructing them since I didn’t want to throw anything out (similar to the Indigenous principle of using every part of the whole animal). Through that process, I explored other textile art practices besides sewing, which led me to weaving.

I specifically learned the Basahan weaving technique, a decades-old practice that evolved from traditional Indigenous weaving cultures in the Philippines as a resourceful way to manage and reuse the excess amount of secondhand clothing. The process is done on a handmade loom and purposefully uses “retaso” which is scraps of cloth material like old T-shirts, cut into strips. Hence, the Tagalog word “basahan” meaning “rags” refers to mats commonly made using this method. After learning this technique, I created pieces for an installation titled Balikbayan which featured a handmade loom built from a discarded pallet skid that holds a woven textile fashioned out of silk organza fabric scraps. It also featured another textile that resembles a basket, which represents using already available resources and ancestral knowledge carried through generations. “Balikbayan” means a Filipino visiting or returning to the Philippines after a period of living in another country. It comes from two Tagalog words: “balik” which translates to “return” / “go back” and “bayan” meaning “country.” The creation process for this was a way for me to "go back" by (re)connecting with my cultural roots and indigeneity in the Philippines.

Basahan loom with woven textile, handmade with found materials — discarded pallet skid, nails and silk organza fabric scraps, 2022. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Can you tell us a bit about your current artistic practice and where you draw inspiration from? How do traditional Filipino weaving cultures and/or your Filipinx identity influence your work?

Apilado: I've been weaving pretty consistently since 2022. My work’s main motivation and inspiration have always been to connect with my Lola and my ancestors — whom I don't know too much about — through this craft. In a way, remembering and doing this work feels like mending a tattered or damaged fabric. It has been a slow but healing process on multiple levels — personally, ancestrally and even on a community level. The similar stories that have been shared with me from other Filipinx diaspora since sharing my own has been a beautiful, healing experience. It's a reminder that doing this work and sharing our stories is important. It's what connects us back to our ancestors, ourselves, our culture and our community.

Anne: As an artist, I’m dedicated to creating conceptual or functional things from what’s seen as “waste.” I enjoy the creative process of figuring out how to make things from discarded materials and avoiding using new items when possible. I’ve always been interested in the spirit of sustainability, even before the term was popularized. My intrinsic values as a person and artist were then fully realized when I took Indigenous Fashion Studies in school. The course focused on rich cultural traditions that were taken away or lost from colonialism to build the fashion industry through globalization. I learned how making clothing originates from the traditional craft and art of textiles, which has been devalued and underappreciated since it was industrialized for capitalism. Recognizing all of this really influenced me and my artistic practice; I became more passionate about (re)working clothing and textiles to create wearable art and installations that visually communicate these complex topics. I began leading textile workshops to promote slow fashion and conscious living as a reminder of our interconnectedness as threads woven into this social fabric.

I’m also inspired by Indigenous artisans and makers in the Philippines, as well as other Asian cultures. I feel that my Filipinx identity and my grandmothers are my greatest influences. My grandmother, who passed before I was born, was a seamstress, and my dad told me about how she would use newspapers for patternmaking. My other grandmother would tell me to never throw out the fabric cuttings from my sewing projects because I could still make other things with them. While their habits might’ve stemmed from a scarcity mindset of growing up in poverty in the Philippines, it’s evident that sustainability was simply their way of life and an inherent part of the culture. These connections are why I’m naturally drawn to this intentional artistic practice when working with textiles — it’s like an instinctual way of carrying on the wisdom and legacy of my grandmothers.

Basahan style textile basket woven with silk organza fabric scraps, carrying bouquet of garden and store bought flowers 2022. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Pacita Abad worked extensively with textiles, both from the Philippines and from cultures around the world. As an artist working with textiles, what comes to mind when you experience Abad’s work?

Apilado: I first heard about Abad a year ago when her work was being exhibited at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA). I decided not to research anything about her work until the exhibition reached Toronto, and I'm glad I waited because seeing her work for the first time earlier in early October was...it's hard to put into words. It was an emotional experience. Honestly, it was life changing.

A part of me feels sad and angry and questions why it took so long for the world to be introduced to her work. Why did it take 20 years after Abad's death for her to be recognized and celebrated? When she was alive, why did she receive about 100 rejection letters from galleries, including spaces that have now recently exhibited her work? Why wasn’t she worthy enough for institutions back then? Why is her work valued now? Why was she kept from us all this time? But the other part of me is just grateful to have the opportunity to see her work right now. Through her work, you can see how prolific, strong, politically outspoken and brave she was. How sensitive she was. How funny she was. She was a bright light — something the world really needs right now.

I wish her work was known and accessible years ago, especially as a younger person because when you see monumental works like hers in a space like the AGO, these are the kinds of experiences that can change a person's worldview. A whole world of possibilities is opened up. To see another Filipinx creating art and being celebrated for it? To see yourself in someone else's work? It's so important. Powerful.

Carol Ann Apilado, Channel, 2023, cotton and cottolin (cotton/ linen), stones, and pillow, approximately 4' diameter, 12' high. Image courtesy of the artist.

Anne: With the current politics surrounding the AGO since last year, including the departure of Wanda Nanibush, former AGO Curator of Indigenous Art, it’s been very difficult to navigate how to feel about Abad’s work being exhibited here. It’s even more confusing as the AGO describes Abad’s work to be “defined by her engagement in social justice.” It’s really complex trying to hold space for the duality of emotions knowing the role and influence funded art institutions have in these situations, while also being excited to see more racialized artists featured and wanting to celebrate the first Filipina artist to have a solo exhibition at one of the largest art galleries in Canada.

But after taking everything into consideration, I do think it’s valuable to see and experience Abad’s work in person — particularly for us Filipino/a/x’s. It was amazing to see her actual pieces up close and it’s impressive looking at her fine needlework by hand on such large scales, which I resonated with because I understand the slow nature of sewing and other textile practices with continuous repetitive motions. I admire all the details of her work, including her delicate stitching seen behind some of the pieces, which are a display of art on their own. I appreciate her colourful use of various textile design methods to create texture as I also like to play around with different textile techniques and continue to be curious about other ways to work with textiles. I especially appreciated how she used her art for political expression by creating Marcos and His Cronies (1985 - 1995) during the danger of the Marcos dictatorship. Abad was very progressive during her life, so it feels as though she transcends time with her works weaving the past, present and future.

Amidst the Pacita Abad exhibition, what do you hope participants take away from this workshop?

Apilado: After our workshop, I hope participants understand the importance and power textiles have and the stories they tell. I hope people ask questions such as: What is the name of the weaver who handwove this? What do the colours represent? What do the symbols and patterns mean? Does the symbol represent a certain time in history when it was made?

I also hope participants see traditional craft and textile work as valuable fine art. Textile practices and work are often overlooked and undervalued. It's a fine craft and art and should be seen and treated as such.

Lastly, I hope that everyone, not just Filipinxs, start to ask more questions about their family history and what traditional crafts their ancestors practiced. It's not only a beautiful way to connect to our ancestral roots but to connect with ourselves. Why are we drawn to certain crafts and ways of creating? Is there a connection between that and what our grandparents or great-grandparents did? Learning our stories and where we come from is invaluable, a way to empower ourselves. As Filipino revolutionary José Rizal once said, “Know history, know self. No history, no self.”

Carol Ann Apilado, Channel, 2023, cotton and cottolin (cotton/ linen), stones, and pillow, approximately 4' diameter, 12' high. Image courtesy of the artist.

Anne: For both artists and viewers, art and creativity have the power to influence our culture and can shift mindsets to encourage more radical action. I believe art can be used as a tool for social and revolutionary change when we collectively re-envision our future. As best said by Abad herself, “I have always believed that an artist has a special obligation to remind society of its social responsibility.”

I hope Pacita Abad and my AGO workshop series titled Textile Art as Reclamation inspire participants to feel more creatively motivated and connected to their cultural identities. The workshops will prompt deep reflections about the fabric of our society through different activities inspiring cultural reclamation, as well as literal material reclamation. The weaving workshop is an introduction to this art form, intended to revive and promote this practice but with modern methods using found materials. This activity aims to remind us of this cultural craft, but also how textiles are made to encourage a slow and conscious fashion mindset. For my screen printing workshops, participants will learn how to silk screen protest art I’ve designed on salvaged textiles and learn basic sewing skills. The fabric prints can be used as patches to repair or sew onto clothing, worn as a political statement and resistance fashion.

Through these workshops, I also hope that the creative process will initiate critical conversations and encourage us all to be more intentional in our everyday lives, from rethinking and redefining our perceptions of waste to unravelling the threads of resilience and optimism that reawaken our sense of place in this social fabric. Textiles are a powerful medium for expressing our identities and storytelling, it’s an art and act of resistance.

To learn more about Carol Ann Apilado and Norwin Anne’s November 6 workshop, see here. To learn more about Norwin Anne’s solo workshop sessions, see here. All workshops in this series are free to attend.