Four materials you can touch in Making Her Mark

That’s not a typo. Here are four materials women makers used that you can touch included in the exhibition

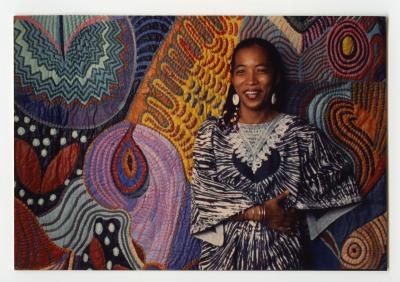

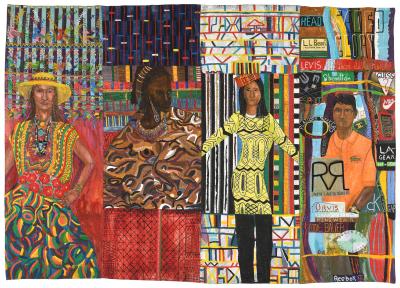

Installation view: Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800, March 27, 2024 - July 01, 2024, Art Gallery of Ontario. Photo © AGO.

It’s widely known that touching the art and objects in a museum is a no-go. From glass encasings to grip tape on the floor reminding you to keep your distance, touching art is not often on the table.

While you still can’t touch the art for its protection and longevity, an exhibition at the AGO gives visitors the chance to use their hands to get more acquainted with the materials women makers used to create art.

Currently on view at the AGO, Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400 - 1800 highlights the contributions of women artists and makers in Europe by bringing together more than 230 objects spanning various mediums.

In honour of the unique range of materials on view, the exhibition includes tactile labels that allow visitors to touch examples of select mediums. The tactile labels give visitors a deeper understanding of the level of skill required to work with these materials.

When you see this symbol in the exhibition, feel free to touch the materials displayed on the tactile label.

Here are four materials you can touch at Making Her Mark, with corresponding works on view.

1. Rolled Paper

Sophia Jane Maria Bonnell and Mary Anne Harvey Bonnell, Paper filigree cabinet on stand, c. 1789. Wood, paper, metallic paper, silk, hair, and adhesive. 105.4x58.4x39.4 cm. Baltimore Museum of Art: Decorative Arts Acquisitions Endowment established by the Friends of the American Wing, 2022.78. Photography courtesy Carlton Hobbs LLC.

Paper may not be a unique material to see in an art museum, but what about art created with thousands of rolled-up paper slips?

Paper-rolling, also known as quilling or paper filigree, was popular among women in the 1700s. During this time, women’s magazines began selling paper-rolling kits with pre-cut coloured paper and patterns. It is believed that paper-rolling began in Ancient Egypt. In pre-modern Europe, paper-rolling was used in both the domestic sphere and for religious works.

You can find this tactile label beside Quillwork (paper filigree) picture with Madonna and Child (1700s). As demonstrated in this work, the paper used in paper-rolling could be coloured or covered with gold or silver leaf to enhance the ornamental nature of the work. Paper-rolling was the chosen medium for many women because of its affordability, as it imitated more costly decorative material such as real gold and silver filigree work. This practice also added the illusion of depth to objects.

In the domestic sphere of pre-modern Europe, paper-rolling was used to decorate tea caddies, workboxes, and furniture because it imitated expensive wood inlay. This can be seen in Paper filigree cabinet on stand, created around 1789 by Sophia Jane Maria Bonnell and Mary Anne Harvey Bonnell.

A rarity, Paper filigree cabinet on stand is one of less than seven surviving furniture pieces completely covered in rolled paper. Due to the delicate nature of paper, only a few pieces such as this cabinet survived the wear and tear of everyday life. To decorate furniture, women would order a carcass, which was a simple wooden base. They would then attach thousands of rolled paper slips to create a design.

Find the rolled paper tactile label in the Personal Devotion section of Making Her Mark.

2. Horsehair

While the paper-rolling on Paper filigree cabinet on stand is impressive, it’s not the only unique material used to create this work.

The front of the cabinet features two intricate rural landscapes embroidered with horsehair. A tactile label with a tuft of horsehair is beside Paper filigree cabinet on stand. You can feel how coarse and thick the horsehair feels compared to cotton threads normally used in embroidery work.

Art created with hair was called “hairwork,” and was widely popular from the late 1700s to the 1800s. Usually, the hair incorporated into embroidery and jewellery had sentimental value, often coming from loved ones. Dr. Alexa Greist, co-curator of Making Her Mark, describes this in more detail in the following video.

3. Beaded Embroidery

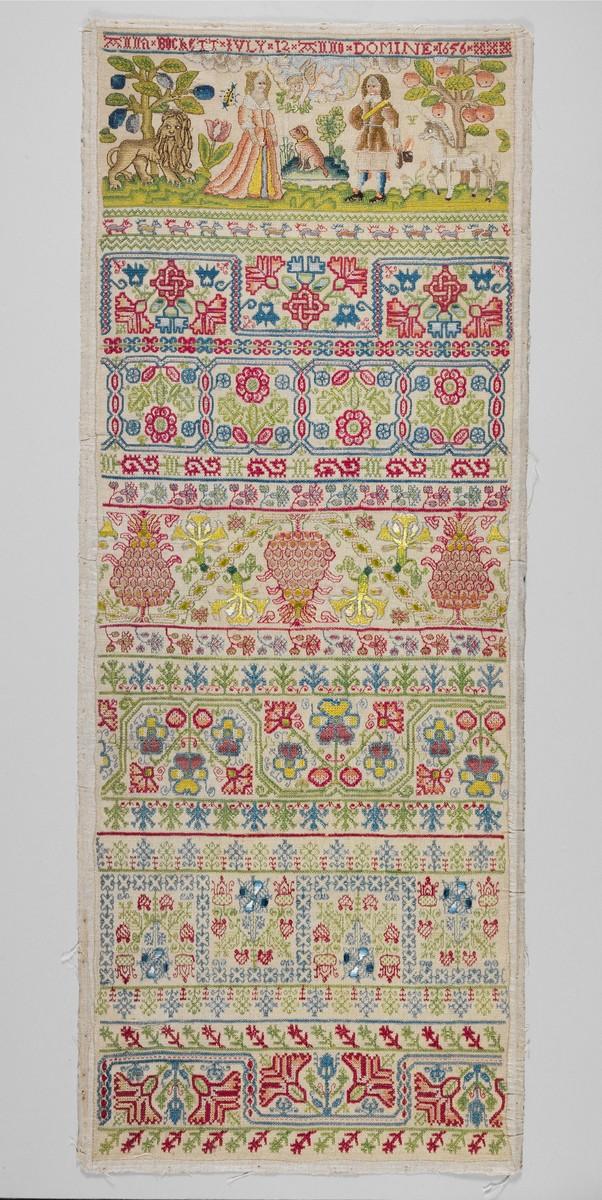

Anna Bockett, Sampler, 1656. Linen worked with silk thread; long and short, split, stem, back, tent, cross, and satin stitches, 70.8 × 26.4 cm. Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964, inv. no. 64.101.1327.

Whether it was a loved one’s hair, metallic thread, beads, or simply common cotton thread, the art of embroidery was an important skill practiced by many women in pre-modern Europe.

Mothers often taught their daughters to embroider, and at the centre of a young woman’s embroidery education was a sampler, a long piece of embroidered work demonstrating her skills. Samplers included autobiographical elements, with many young women portraying aspects of their lives such as their names and ages, buildings in their communities, and even their aspirations. On view in Making Her Mark is Anna Bockett’s sampler from 1656, which includes a scene depicting the courting of a man and woman, likely signaling the happy marriage Bockett hoped for.

Furthering the sentimental nature of embroidering, many women created works for their loved ones, such as the nightcap embellished with sequins and metallic thread on view beside the beaded embroidery tactile label. A girl or woman created this nightcap for either a husband, father, brother, or son.

Unknown British Embroiderer, Man's nightcap, c.1580. Linen plain weave embroidered with silk, metallic thread, and metal sequins, and trimmed with metallic-thread lace, Height: 25.4 cm. Lent by Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence, Helen M. Danforth Acquisition Fund. 1987.042. Image courtesy of the RISD Museum, Providence, RI.

Women also embroidered things for themselves, including the very containers they kept their supplies in. These small tabletop boxes called caskets or cabinets were often projects women took on towards the end of their needlework education due to their elaborate and time-consuming nature. The two embroidered cabinets on view in the exhibition have become a rarity, partly because textile goods were often destroyed during times of contagion.

Embroidery also occurred outside the domestic sphere. Surprisingly, women worked alongside men in professional workshops. Despite embroidery being closely associated with women’s education, a gender hierarchy remained in these workshops. Men took on the high-status jobs of transferring designs and cutting pieces while women did anonymous embroidery work.

Find the beaded embroidery tactile label in the Domestic Sphere section of Making Her Mark.

4. Lace

Unknown. Flemish Bobbin Lace Collar, mid-late 17th century. linen, 259.1 x 6.4 cm, 109.2 x 6.4 cm, 150.0 x 5.1 cm, 77.5 cm, 71.1 x 7.6 cm (collar). Baltimire Museum of Art: The Cone Collection, formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Maryland; 1950.2022.268

As you examine the numerous works made of lace on view in Making Her Mark, you may notice most of the creators are unknown. A common theme stretching across the exhibition, the anonymity of women makers can be attributed to a few factors: a lack of access to art education and professional opportunities; socioeconomic factors such as race, gender, and class; familial demands; and high mortality rates during childbirth.

Lacemakers specifically remained unknown because they operated outside the male-dominated guild system. Most lace was made by women living in convents and low-income women. Yet, it symbolized luxury in pre-modern Europe, often used to embellish the clothing and furniture of the wealthy. Its high status and demand were due to the time-consuming nature of the craft. Some patterns took at least one hour to make only one square inch of a work.

Unknown. Milanese Bobbin Lace Flounce for an Alb, late 17th-early 18th century. linen, 144 x 16-1/4 in. (365.8 x 41.3 cm). Baltimore Museum of Art: The Cone Collection, formed by Dr. Claribel Cone and Miss Etta Cone of Baltimore, Maryland; 1950.2022.269.

By the 1660s, lacemaking had become such a lucrative industry that Louis XIV barred the import of foreign lace. In response to this edict, the controller-general of finances, Jean-Baptiste Colbert, developed lace manufactories across France and recruited Venetian and Flemish lacemakers to train local women in the latest styles. The Venetian Republic then declared practicing lacemaking abroad as espionage, punishable by imprisonment or execution. Eventually, the demand for handmade lace sharply declined with the creation of lace machines during the Industrial Revolution.

Needle and bobbin methods were the two most common ways to make lace by hand. Needle lace is created by tracing a pattern with a needle and a singular thread while bobbin lace uses multiple threads tied around bobbins, which are then twisted and crossed to create patterns.

While the lace makers on view in the exhibition remain anonymous, historians can often tell their country of origin or where they practiced from the techniques and patterns they used. Specific patterns created in combination with either technique became associated with different European countries and regions. On view in Making Her Mark is a selection of lace from areas such as Northern Italy, France, and Russia.

Find the lace tactile label in the Powerful Patrons section of Making Her Mark.

Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800 is co-organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario and the Baltimore Museum of Art. The AGO presentation is on view on Level 2 of the Gallery through July 1. The exhibition is co-curated by Dr. Alexa Greist, AGO Curator and R. Fraser Elliott Chair, Prints & Drawings and Dr. Andaleeb Banta, BMA Senior Curator and Department Head, Prints, Drawings & Photographs.