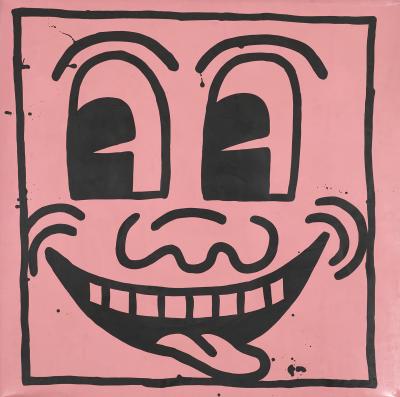

Four artistic heroines you should know

Josefa Ayala, Anna Bockett, Anne Guéret and Sarah Stone – meet four women artists in Making Her Mark

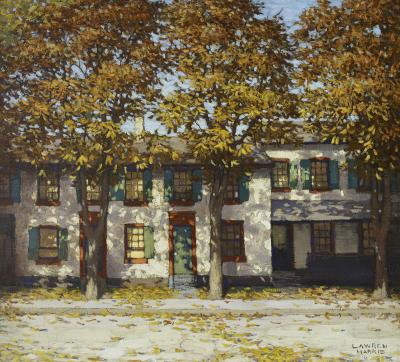

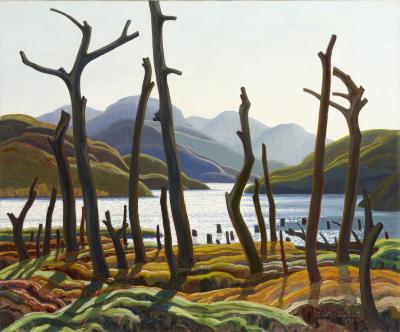

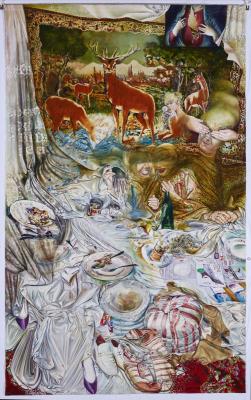

Sarah Stone. A blue and yellow Macaw, after 1789. Watercolour heightened with opaque watercolour and glazes, with a black ink border, Sheet: 44.1 × 33.9 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Purchase, with funds from the Marvin Gelber Fund, and the Master Print & Drawing Society, 2022. Photo © AGO. 2022/7043

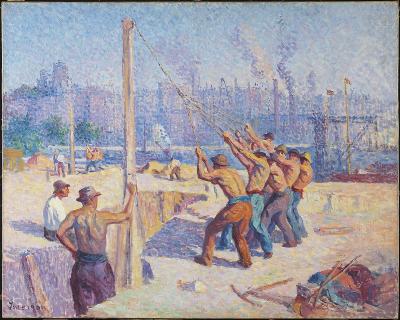

In an expansive showcase, Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400-1800, brings together 230 objects in various mediums by over 130 women artists and makers, some known and others yet to be known. The AGO and the Baltimore Museum of Art co-organized this groundbreaking exhibition, on view at the AGO on Level 2 through July 1.

Although some of the biographical details of these women artists and makers are sparse, there is still much to uncover about the skills, influences and symbolism behind their work. Here are four lesser-known women who, against the odds, defied the societal expectations of their time to make art in a world dominated by men.

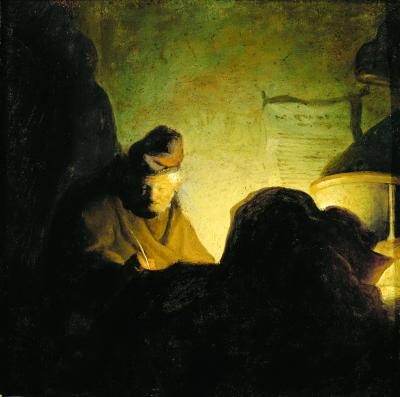

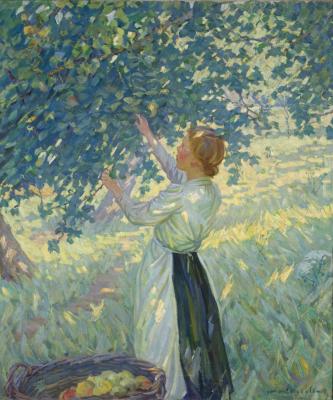

Anne Guéret, 18th-century portrait painter

French, lived c.1760 to 1805

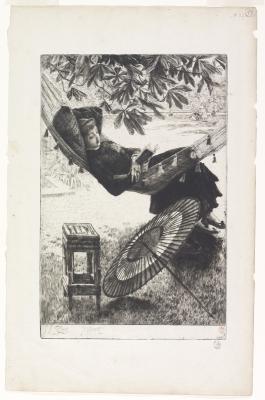

Anne Guéret, Portrait of an artist with a Portfolio (Self-Portrait?), c. 1793. Black chalk, pen and gray ink and wash, heightened with white gouache on paper, 32 × 40.4 cm. Katrin Bellinger Collection. 2008-012. Photo: Matthew Hollow.

What could be so revolutionary about a portrait of a young woman drawing? From a 21st-century perspective, this drawing by French artist Anne Guéret might seem rather straightforward. However, upon closer inspection, it signals a pivotal turning point in the history of women artists in Europe.

As explained in the exhibition, Guéret was one of dozens of women who studied under the Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David, challenging the narrative that women artists were denied access to official channels of education until the late 1800s. This drawing, her debut work at the 1793 Salon in Paris, depicts a young woman, possibly modelled after Guéret herself, seated in a relaxed and self-assured pose, her body turned away from her drawing board. The seated woman has drawn a nude male figure but it's unlikely that Guéret drew this figure from a live model. Instead, it’s more likely that she drew from a print or sculpture. The fact that she drew a nude male figure suggests a progressive shift in attitudes towards women artists of the late 18th century.

Anne Guéret's Portrait of an Artist with a Portfolio (Self-Portrait?) (c.1793) is in the Fashioning the Woman Artist section of the exhibition and appears on the front cover of the exhibition catalogue.

Sarah Stone, 18th-century natural history painter, illustrator and exhibitor

British, lived c.1760 to 1844.

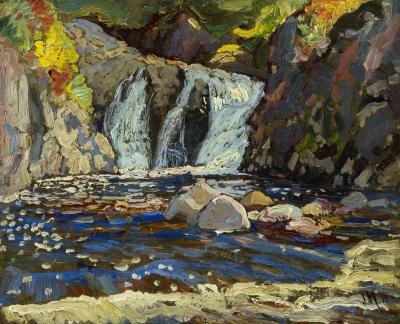

Born in London, Sarah Stone is believed to have had an affinity for painting since childhood, likely developed under the influence of her father, a fan painter. When Stone was a teenager, the collector Ashton Lever hired her to record the now-dispersed holdings of his Leverian Museum in England. As explained in Making Her Mark's exhibition text, Lever’s collection exemplified the colonial exploits of the time, including Indigenous artifacts and animals the British seized on their expeditions to the Americas, East Asia, and Australia. Lever had many taxidermized specimens from around the world in his collection, and Stone recorded several of them. However, the eye-catching 1789 painting of a blue and yellow macaw (image at top) is a composition she made independently.

Stone's illustrations for the Leverian Museum established her reputation and launched her career as a painter and illustrator. She even became an exhibitor at the Royal Academy of London and the Society of Artists. During her career, she is said to have made thousands of paintings and illustrations, some of which today are included in private and public art collections. The AGO added this painting to its Collection in 2022. Many of her works still need to be accounted for.

Sarah Stone’s The Blue and Yellow Macaw (after 1789) (image at top) is in the Natural Empire section of Making Her Mark.

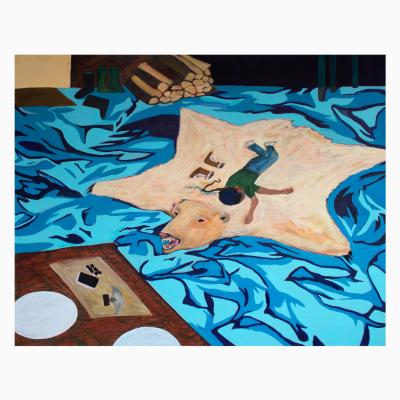

Anna Bockett [sometimes documented as Anna Buckett], 17th-century embroiderer

British, lived during the 17th century (exact years unknown)

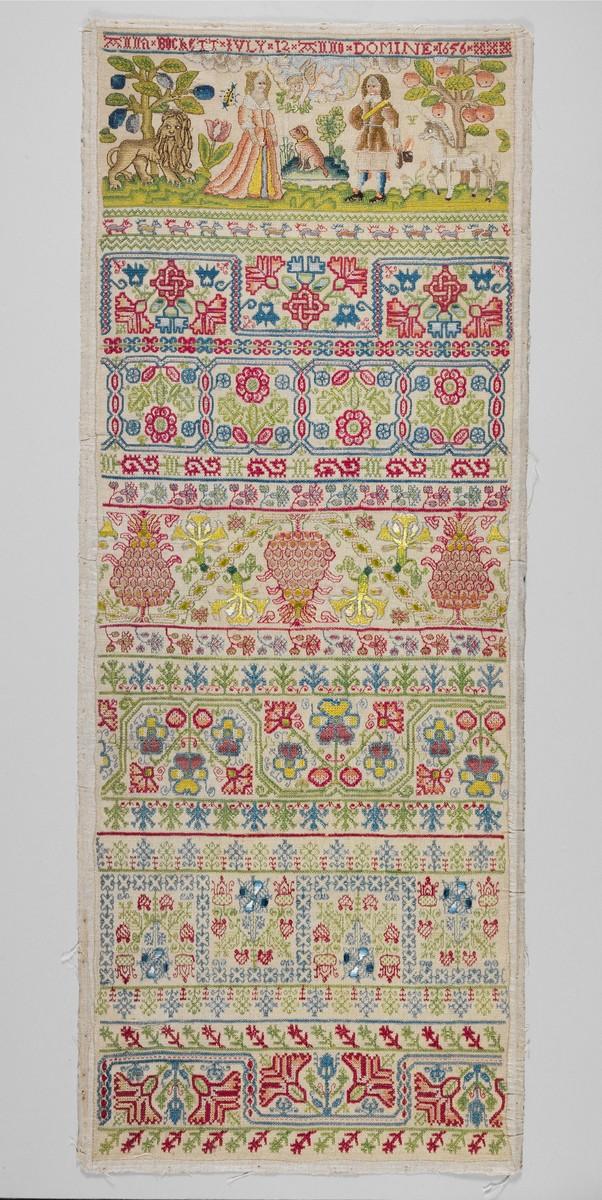

Anna Bockett, Sampler, 1656. Linen worked with silk thread; long and short, split, stem, back, tent, cross, and satin stitches, 70.8 × 26.4 cm. Lent by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964, inv. no. 64.101.1327.

For girls as young as eight in 17th-century England, learning to embroider was a core part of their education. Usually, under an instructor's supervision, girls learned needlework techniques and skills, honing their stitches and demonstrating their skills with samplers. “Samplers range from the solely practical to the highly decorative,” write Isabella Rosner and Theresa Kutasz Christensen in the Making Her Mark exhibition catalogue, “they are both educational exercises and biographical documents, providing unique glimpses into the lives of the girls who stitched them, with their inclusion of names, dates, and ages.”

On loan from The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the sampler above is a band sampler, characterized by horizontal bands stitched on linen with silk thread. It was made by a British girl named Anna Bockett, who lived during the Commonwealth period when Oliver Cromwell was Lord Protector of England. Bockett inscribed her name and exact date on this sampler—July 12, 1656— perhaps indicating when she began or ended stitching it. Look closely at the top horizontal band to see the picturesque courtship scene Bockett stitched. It features a young couple, complete with Cupid flying overhead and a seated dog, both symbols of enduring love, possibly indicating her aspirations for her future marital union.

Anna Bockett’s Sampler (1656) is on view in the The Domestic Sphere section of Making Her Mark.

Josefa Ayala, 17th-century painter of still lifes, altarpieces and devotional works

Portuguese, lived c.1630 to 1684

Josefa Ayala holds the unique title of the only documented independent female painter from 17th-century Portugal. Like Sarah Stone in the 18th century, Ayala’s training in painting was likely undertaken in the workshop of her father, Baltazar Gomes Figueira, a military man turned painter. She did, however, work independently from any of her male family members. Ayala produced some of her earliest work while boarding in an Augustinian convent, as was commonplace for religious, unwed girls and women of the late 17th century. As she entered her teenage years and into adulthood, she continued to hone her skills as a painter by taking on public commissions by prominent patrons.

Following her father’s death, she forged ahead as a painter and amassed a self-made fortune—almost unheard for a woman at that time. Her success as a painter and the high commercial value of her work was partly a testament to her artistic talents and her use of copper as a support medium. "The exquisite work of Portuguese painter Josefa Ayala (c. 1630–1684)," writes Dr. Andaleeb Badiee Banta and Christensen in the Making Her Mark exhibition catalogue, "highlights her access to materials obtained through Portugal’s influential role in extractive trade in West Africa and India, including some of the copper on which she painted, as well as her personal ownership of a collection of Portuguese silks and taffeta from India that she studied for the garments on her painted figures.” Ayala was also a devout Catholic woman; many of her devotional paintings reflect that sensibility.

Paintings by Ayala are included in the Powerful Patrons, Domestic Luxury and Personal Devotion sections of the exhibition.

Making Her Mark: A History of Women Artists in Europe, 1400–1800 is co-organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario and the Baltimore Museum of Art. The AGO presentation is on view on Level 2 of the Gallery through July 1. The exhibition is co-curated by Dr. Alexa Greist, AGO Curator and R. Fraser Elliott Chair, Prints & Drawings and Dr. Andaleeb Banta, BMA Senior Curator and Department Head, Prints, Drawings & Photographs.

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)