Remembering Alex Janvier

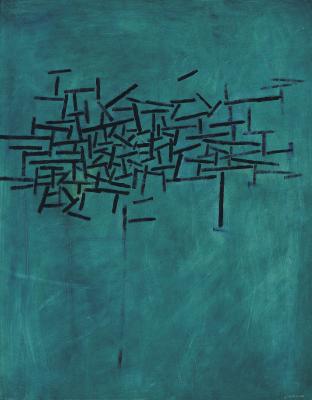

The renowned Denesųłiné artist revolutionized the possibilities of abstraction

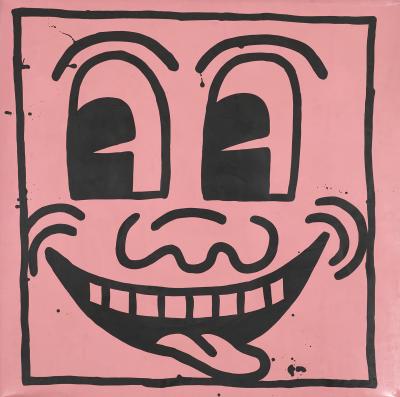

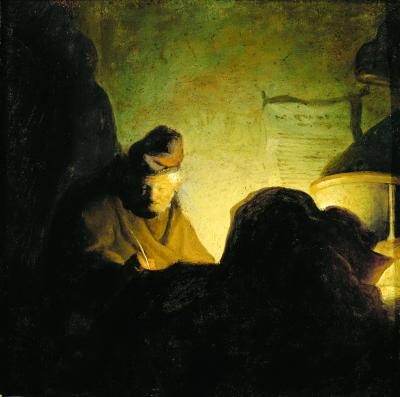

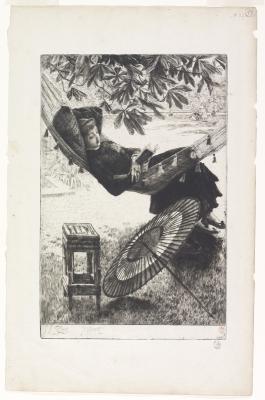

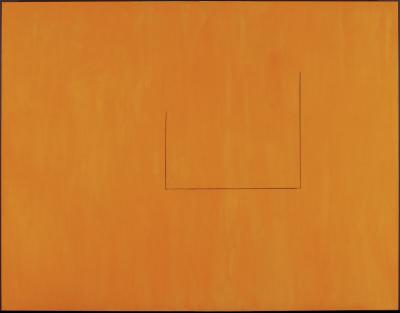

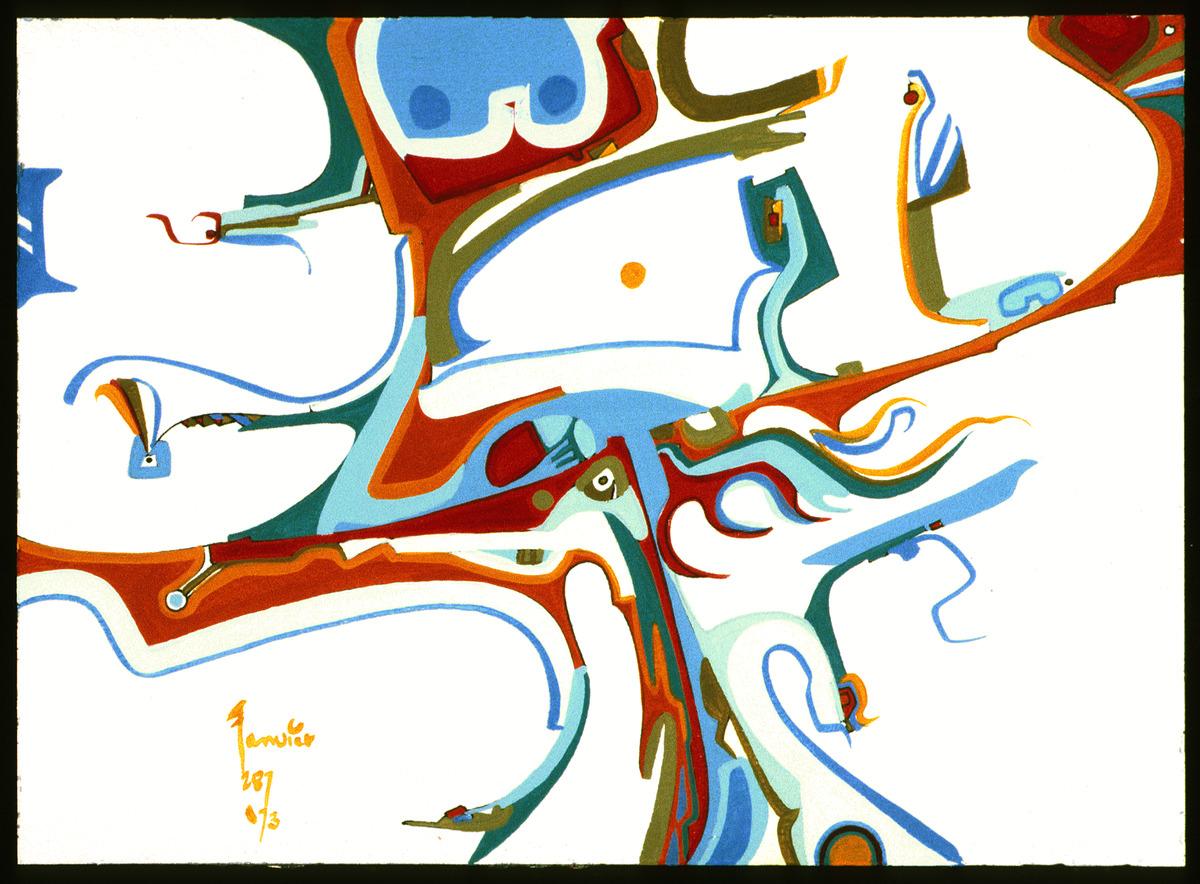

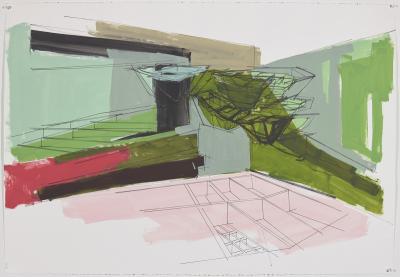

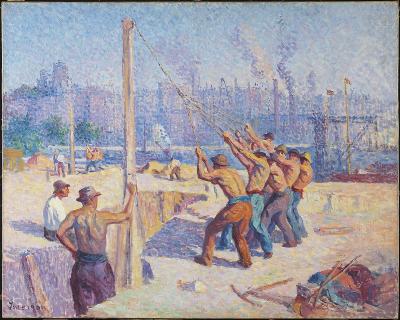

Alex Janvier. Untitled, 1973. Pen and ink and acrylic on woven paper, 27.8 x 38 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift from the Collection of Dr. Michael Braudo, 2000. © Estate of Alex Janvier. 2000/156

With fluid lines and vibrant colours, Alex Janvier surpassed boundaries while creating intricate abstractions of Indigenous life.

Janvier recently passed away at the age of 89. He was known for his distinct style, which merged traditional Indigenous art such as porcupine quill work, beadwork, and birch basketry with post-war global art approaches. Janvier’s bright colour combinations and calligraphic lines were heavily influenced by his Denesųłiné culture, heritage and relations to the land.

Janvier was born in 1935 and grew up on the Le Goff Reserve of Treaty 6 in Cold Lake Alberta, speaking the Dene language. At the age of 8, he was forced to attend Blue Quills Residential School in St. Paul, Alberta, as mandated by Canadian government assimilation policies. Janvier shared on his experience at Blue Quills: “Fortunately, I had a good foundation in my language. I learned from the old people, the elders and old ladies, and they made sure I was well instructed in my language, in my culture and in my livelihood.”

During his time at Blue Quills, Janvier began to paint. In 1960, Janvier graduated with a Fine Art diploma from the Alberta College of Art and Design (formerly known as the Alberta Institute of Technology and Art) and began teaching adult art classes at Saddle Lake Indian School near St. Paul until he decided to become a full-time artist in 1972. This decade marked a critical time in the artist’s career. As he developed his distinctive artistic vision, he also became a founding member of the Professional Native Indian Artists Inc. (PNIAI).

Also known as the “Indian Group of Seven,” a pointed riff on the Group of Seven, the collective consisted of fellow Indigenous painters Norval Morrisseau (1932-2007), Jackson Beardy (1944-1984), Eddy Cobiness (1933-1996), Daphne Odjig (1919-2016), Carl Ray (1942-1978), and Joseph Sánchez (born 1948). PNIAI advocated for recognition, inclusion, and accessible and equitable arts funding for Indigenous artists. In Janvier’s own words, PNIAI “upset the establishment. They themselves accepted that we were good enough. Plenty good enough.”

Janvier developed and painted in his own language. He rejected the notion that modern art should not include culturally specific references. His paintings incorporate his cultural and spiritual heritage, and he found inspiration in his relationship with the land. In an artist statement for the Alberta Biennial of Contemporary Art, the artist said: “... there is no separation between man and nature. I am living nature. Our bible is in the land. I am claiming all of the land that belongs to my people through my painting.”

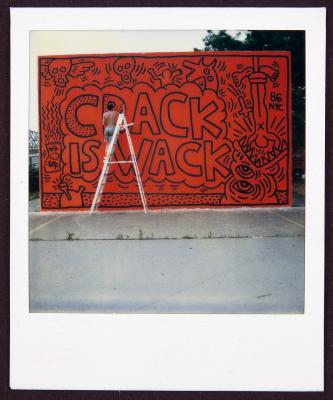

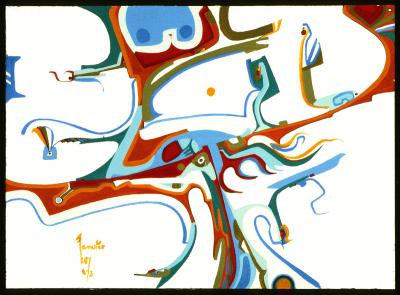

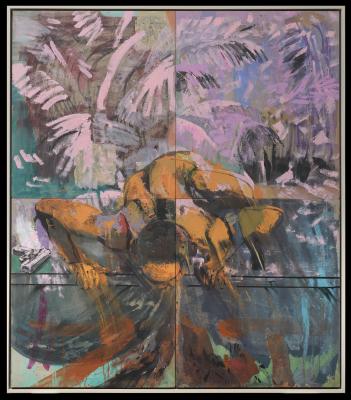

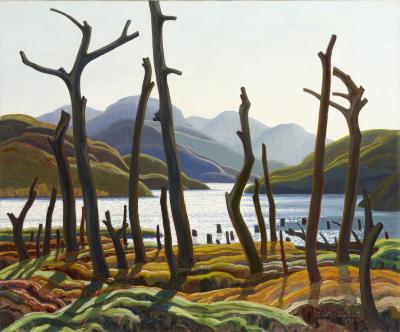

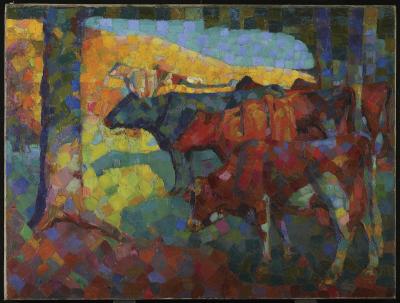

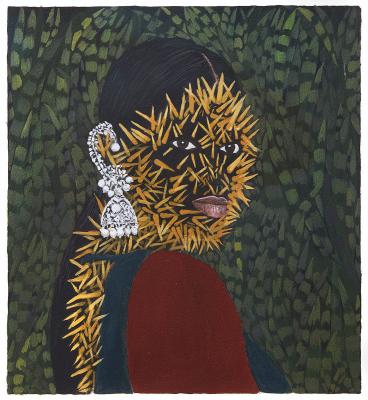

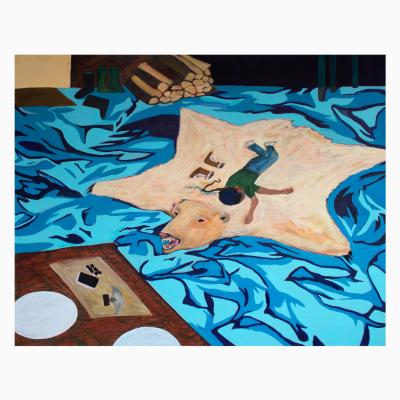

Alex Janvier. Smile Shooter (Life's Scrabble Series), 1994. Acrylic on linen, 152.4 × 130.2 cm. Private collection, Mississauga. © Estate of Alex Janvier.

Janvier also did not shy away from creating political statements in his art. In 1966, Janvier was commissioned by the Department of Indian Affairs to make 80 paintings for a show in Ottawa. After the paintings were exhibited, the government sold 38 paintings and refused to return the rest. As a result, Janvier began signing paintings created between 1966 and 1977 with his treaty number 287 in protest of how the Canadian government treated Indigenous Peoples.

This act of protest can be seen in Janvier’s work on paper in the AGO Collection, Untitled (1973). While this work is not currently on view, visitors can see Janvier’s bold canvas Smile Shooter (Life’s Scrabble Series) (1994), a work currently on loan and on view on Level 2 of the AGO in the J.S. McLean Centre for Indigenous + Canadian Art.

Beyond gallery walls, Janvier shared his work widely by creating public murals across Canada, significantly for the Indigenous pavilion at Expo ‘67 in Montreal, where he invited many Indigenous artists to contribute. In Alberta, Janvier created Tsą tsą ke k’e – “Iron Foot Place” (2016), a 45-foot diameter mosaic mural for the Rogers Place Arena in Edmonton and the diptych SA HAɁA: Sunrise and SA NŲYEɁA: Sunset (2019) for the Alberta Legislative Assembly Chamber. Possibly Janvier’s best-known mural is Morning Star Gambeah Then’ (1993), painted on the dome of the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec. Consisting of a circle divided into four quadrants, each section of the mural represents different periods in Indigenous history: the yellow quadrant represents life pre-European arrival, the blue quadrant evokes the effects of colonization on Indigenous cultures, the red quadrant illustrates the struggle and affirmation of Indigenous beliefs and practices, and the white section represents the journey of healing and reconciliation. At the centre is the radiating Morning Star, the mural’s namesake. As Janvier explained, the Morning Star was used as a guiding light during winter mornings in Denesųłiné culture.

Active until his death, Janvier received countless awards and honorary degrees during his decades-long practice, including Lifetime Achievement Awards from Cold Lake First Nations and the Treaty 6 Tribal Chiefs Institute in 2001, an Order of Canada in 2007, an Honorary Doctor of Law from the University of Alberta in 2008, and the 2017 Distinguished Artist Award from the Lieutenant Governor of Alberta—a small sample of his many achievements and lasting impact.

Experience Alex Janvier’s vibrant and powerful abstractions by visiting Smile Shooter, on view on Level 2 of the AGO in the Molly & George Gilmour Gallery (gallery 233) of the J.S. McLean Centre for Indigenous + Canadian Art.

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)