Tempest in a Hammock

Lucy Paquette’s novel exposes the critical backlash against Tissot’s saucy paintings

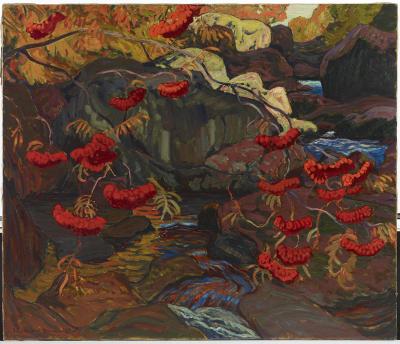

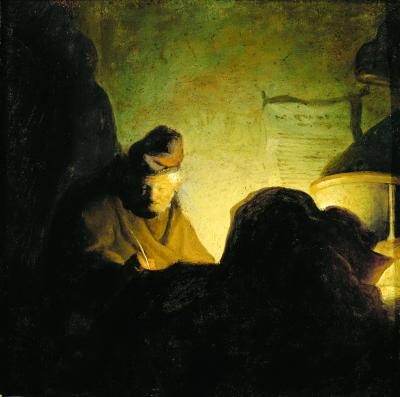

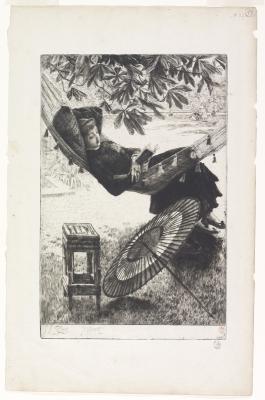

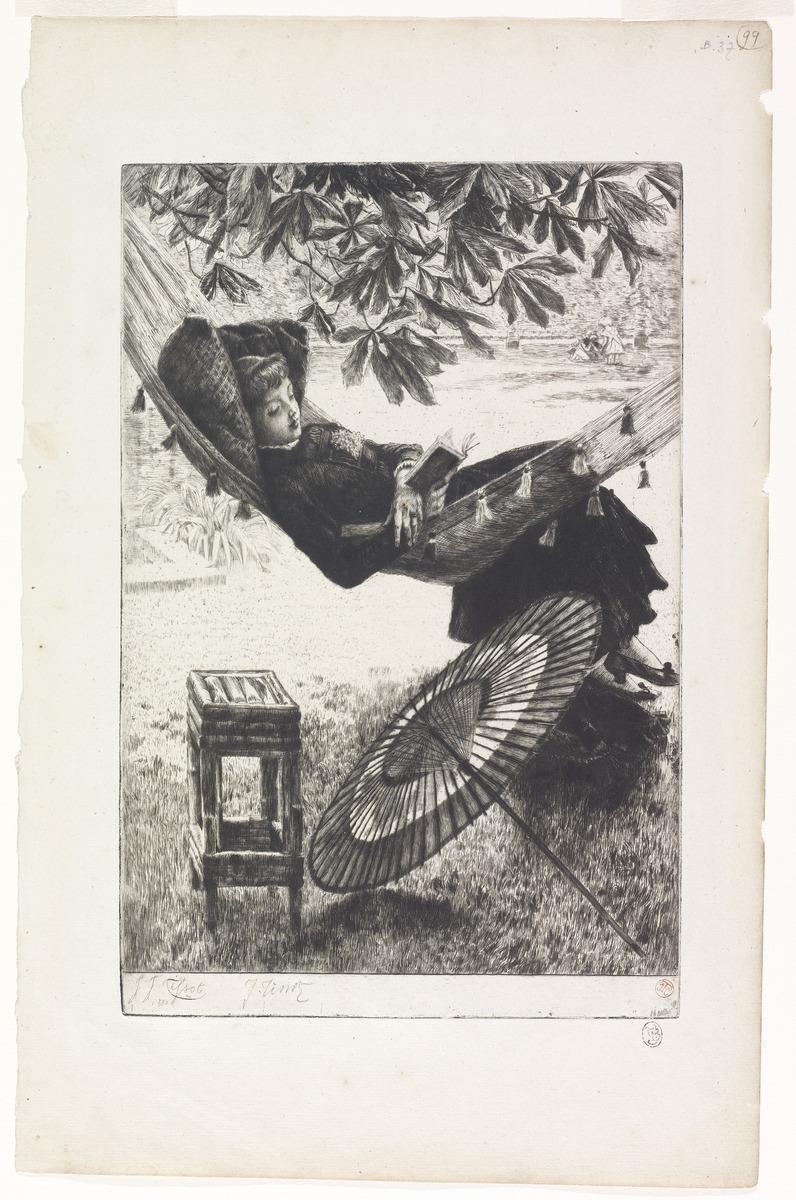

James Tissot. The Hammock, 1880. Etching and drypoint on laid paper, Overall: 37.9 x 24.4 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of Allan and Sondra Gotlieb, 1994. Photo © AGO. 94/237

Among the three paintings and 34 prints currently on view as part of the exhibition Tissot, Women and Time, is an exquisitely composed etching entitled The Hammock (1880). A portrait of a leisurely afternoon, it shows a woman reading a novel under a leafy chestnut tree, her ankle dangling seductively. A Japanese parasol lies on the ground, and children play in the distance. The woman wears a large wedding ring on her finger. She is unnamed, but her face reappears throughout the exhibition – it is James Tissot’s (1836-1902) model and mistress, Kathleen Newton. Famed throughout the 1860s and 1870s for his scenes of modern women, this was not the first time Tissot captured his favourite model reclining on a hammock.

Seen through our contemporary eyes, this image of backyard bliss provides a fascinating window into a complicated historical moment. It is an era, says guest curator Mary Hunter, that cast women “simultaneously as sexual yet innocent, sickly yet seductive, timeless yet modern.”

One of the many remarkable features about The Hammock is that it exists at all.

In 1879, Tissot exhibited three paintings of women reading in hammocks at London’s Grosvenor Gallery. In the prologue to her book, The Hammock: A Novel Based on The True Story of French Painter James Tissot, author Lucy Paquette suggests that the scathing critical response to these paintings, entitled The Hammock , A Quiet Afternoon and Under the Chestnut Tree, ‘shattered his career.’

In his review for the Spectator newspaper, the critic summed up the prevailing opinion: "these ladies in hammocks, showing a very unnecessary amount of petticoat and stocking, and remarkable for little save luxurious indolence and insolence, are hardly fit subjects for such elaborate painting..."

Editors at Punch magazine satirized The Hammock in a thinly disguised verse entitled, “The web.”

Will you walk into my garden?

Said the Spider to the Fly

‘tis the prettiest little garden,

That ever did you spy.

The grass a sly dog plays on;

A hammock I have got;

Eat ankles you shall gaze on – Talk – well, now, time to change the subject.

And across the pond in the US, even The New York Times weighed in: “Mr. James Tissot, one of the eccentrics of the Grosvenor, has sent in eight pictures. They are always of a girl lying on a hammock, or in a swing or lying down, always surrounded by the green grass and green trees so you have to hunt for the figures, and you want to call him names for prostituting his talents to a silly affection of Realism...Under Tissot’s eccentricities lurk a laughing giant.”

Not surprisingly, The Hammock did not find a buyer at the Grosvenor Gallery in 1879. What led to such vitriol? Is it possible that the criticism directed toward Tissot and these works was but a thinly veiled piece of Victorian moralism, targeting his model and mistress Kathleen Newton, with whom he lived?

The couple’s unmarried co-habitation (she was divorced) was certainly scandalous to the Victorian elites who made up Tissot’s audience. “His art was bought by British society, but London high society wouldn’t accept him with his divorced girlfriend,” says Hunter. “Even though France was becoming more and more secular, he was Catholic. You see these complications and tensions in his work. He’s a more interesting figure because he’s hard to read.”

Whatever the reason for the critical backlash he faced (had he like Rembrandt simply passed out of fashion mid-career?), Tissot remained in London until 1882. Following Newton’s tragic death due to consumption, he returned to Paris. His next project, The Women of Paris series -- examples of which are on view at the AGO --, was also poorly received, with one critic complaining that the artist repeatedly painted “the same Englishwoman.”

But of course, this same Englishwoman, who often reappeared in Tissot’s work, was his beloved Kathleen. While critics continued to find fault with these images, it is heartwarming to think that despite it all, as evidenced in The Hammock (1880) his motive was always love. See these beloved works today and decide for yourself!

Tissot, Women and Time is on view on Level 1 of the AGO in Walter Trier Gallery (gallery 139), Nicholas Fodor Gallery (gallery 140) and gallery 141. The exhibition is guest curated by Dr. Mary Hunter, Associate Professor of Art History, McGill University, in conjunction with Caroline Shields, Curator, European Art at the AGO, and Alexa Greist, Curator & R. Fraser Elliot Chair, Prints & Drawings at the AGO.