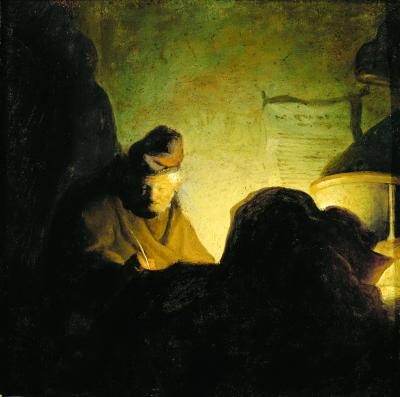

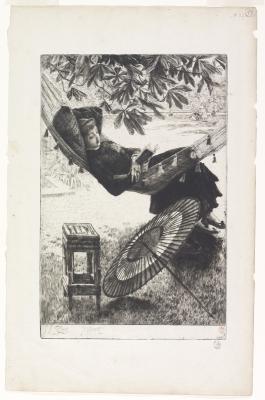

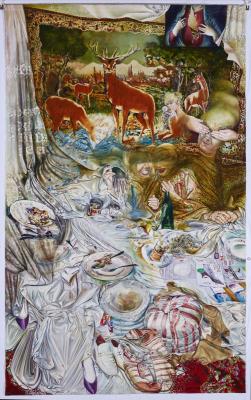

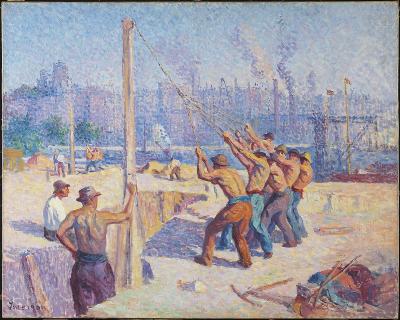

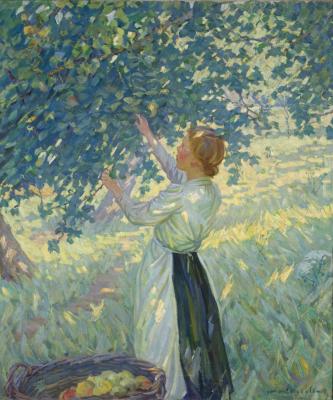

The Shop Girl (La demoiselle de magasin)

James Tissot’s painting takes us inside a 19th-century Parisian shop

James Tissot, La Demoiselle de magasin, c. 1883-1885. Oil on canvas, Overall: 146.1 x 101.6 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift from Corporations' Subscription Fund, 1968. Photo © AGO. 67/55

Around the corner from the Joey and Toby Tanenbaum Sculpture Atrium on Level 1 of the AGO, there hangs a beloved painting by French artist James Tissot (1836-1902), a familiar sight for many of the Gallery’s visitors. The painting is included in the exhibition Tissot, Women and Time, and will be on view until June 29.

Elegantly presented in a 19th-century neoclassical frame from the AGO’s collection, the painting portrays two women working as shop attendants in a Parisian store that sells ribbons, trimmings and fabrics. With a soft smile and parcels in hand, one shop attendant holds the door open for us as viewers-turned-customers. Meanwhile, her coworker reaches up while stocking shelves with merchandise, her head turned towards the gaze of a man wearing a top hat as he looks through the window. “Does the man wish to buy something or is he looking for a date?” asks Dr. Mary Hunter, art historian and guest curator of Tissot, Women and Time. “Through the interplay of gazes, Tissot links commodity culture with desire. The sexual innuendo of window shopping — in French, lèche vitrine translates to ‘licking the window’— is emphasized by the outstretched tongue of the wooden griffin sculpted into the counter's base.” Outside on the boulevard, bustling Parisian life unfolds.

It’s hard not to be intrigued by The Shop Girl (c. 1883-1885) or La demoiselle de magasin in French. This painting is one of 15 large-scale canvases Tissot created between 1883 and 1885 for his series, La Femme à Paris. Each work portrays the everyday lives of fashionable Parisian women from various social classes. For example, both attendants in La demoiselle de magasin represent a particular type of modern woman: feminine, seductive and working class. The “shop girl” was alluring to Parisian society as she symbolized the expanding retail industry (department stores emerged in the 19th century) and evolving fashion tastes. The act of window shopping, as represented by the figures looking through the glass panes, emerged as a new leisure activity made possible by a major rebuilding project that took place in Paris from the 1850s to the 1870s, as well as the recent invention of sheet glass, which allowed for the creation of large windows.

In 1871, after serving in the Franco-Prussian War (1870 to 1871), Tissot left France for England. He remained in England for just over a decade, making a name for himself as a stylish artist in British high society and maintaining ties with fellow French painters like Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet. During this period, he also met and fell in love with the young Irish divorcée Kathleen Newton. Both a lifelong partner and a model/muse, Newton was in a committed relationship with Tissot until her untimely death from consumption. In 1882, a year prior to beginning the La Femme à Paris series, Tissot returned to France, devastated by Newton’s passing. With La Femme à Paris, he staged a comeback to the Parisian art scene, planning an ambitious exhibition of his 15 paintings and corresponding print series, each accompanied by a short essay by a notable French writer. Novelist Émile Zola was chosen to write the story for La demoiselle de magasin.

Despite Tissot’s high hopes, the reception was less than enthusiastic. “Although [he] aimed to showcase his art's modernity, the series ultimately revealed how behind the times his art had become,” explains Hunter in the label text. “Critics panned the works, claiming that he painted ‘the same Englishwoman’ repeatedly. Following the critical failure of his exhibition, Tissot never focused on the theme of modern womanhood again.” The “same Englishwoman” he painted is sometimes thought to be Newton. By 1885, seeking a deeper spiritual connection, Tissot turned his attention to depicting religious scenes, a direction which he continued until his death in 1902.

“It is a pleasure to stand with The Shop Girl, which, despite its scale, feels intimate by way of us already having been invited into this interior space,” says Jane Hutchison, Collection Manager of RBC’s Art Collection. “Like many of the figurative works in the RBC Art Collection, The Shop Girl reflects the cultural context of the moment. The work is unabashed in its subject matter and its confident composition, leaving one wanting to pick up the fallen ribbon and adjust the entrance doormat – perfectly imperfect details that call out this as a place of activity and commerce, keeping in tune with the shifting energies of the city.”

In the exhibition Tissot, Women and Time, on view now, three paintings and 34 works on paper illustrate how, from 1870 to 1885, Tissot often portrayed women of various classes in different settings. He showed them symbolizing the seasons, socializing in the bustling streets of London and Paris, or lounging at home. The AGO currently holds the largest public collection of the French artist’s prints outside the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

Tissot, Women and Time is on view until June 29 on Level 1 of the AGO in Walter Trier Gallery (gallery 139), Nicholas Fodor Gallery (gallery 140) and gallery 141. The exhibition is guest curated by Dr. Mary Hunter, Associate Professor of Art History, McGill University, in conjunction with Caroline Shields, Curator, European Art at the AGO, and Alexa Greist, Curator & R. Fraser Elliot Chair, Prints & Drawings at the AGO.

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)