Just beyond possibility

Curator Sally Frater speaks about what makes Denyse Thomasos’s work so captivating.

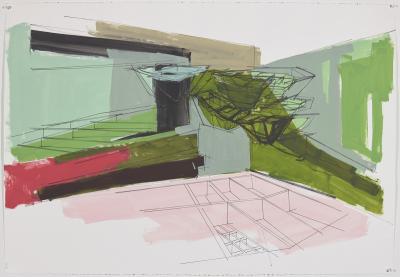

Installation view, Denyse Thomasos: just beyond, October 5, 2022 - February 20, 2023. Art Gallery of Ontario. Work Shown: Babylon, 2005 © The Estate of Denyse Thomasos and Olga Korper Gallery, Photo © AGO

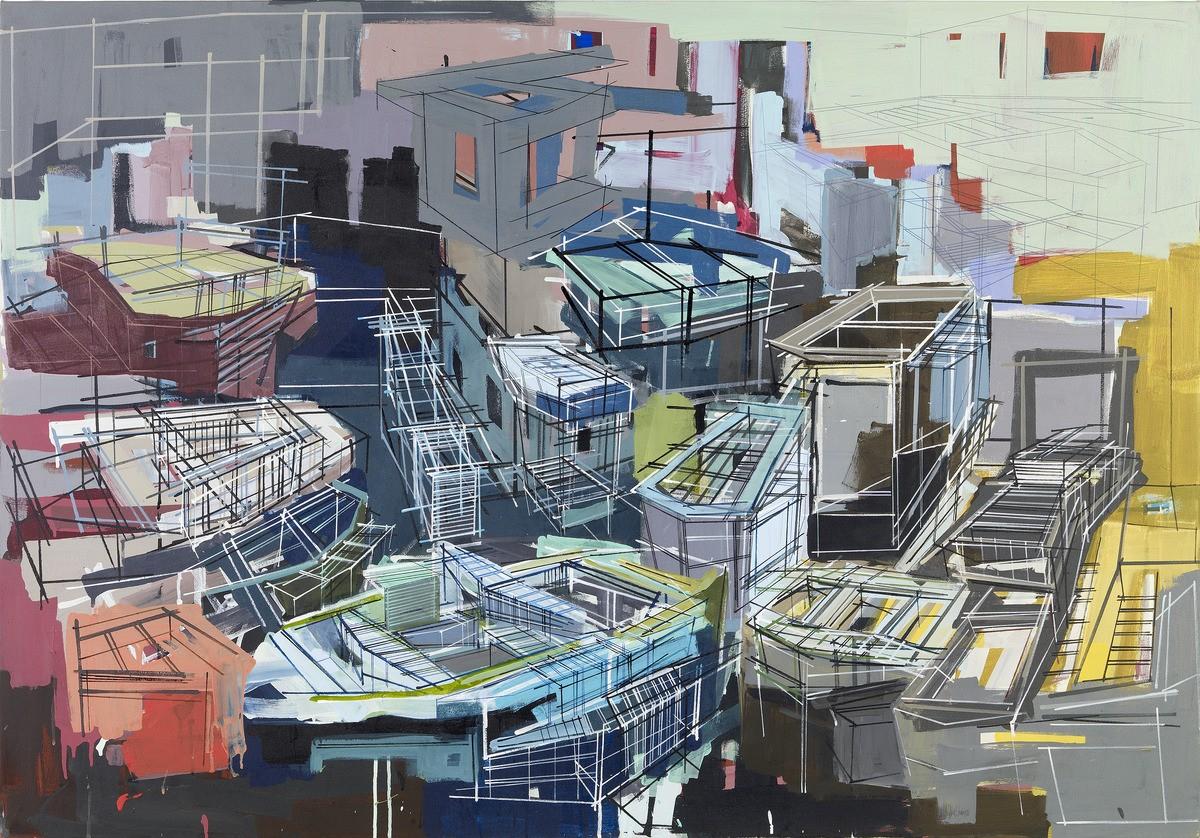

Denyse Thomasos: just beyond enthralled visitors to Level 5 of the AGO. The career retrospective is an expansive, chronological presentation, featuring over 70 paintings and works on paper by the late Trinidadian-Canadian artist. Thomasos’s paintings are a masterful display of colour, line and abstracted forms which envelop the viewer in claustrophobic conditions. Her recreations of the architecture of systemic racism – slave ships, prison cells and low-income housing – remain as relevant as ever.

Sally Frater is one-third of the curatorial team at the helm of the monumental show, along with Renée van der Avoird, AGO Associate Curator, Canadian Art and Michelle Jacques, Head of Exhibitions and Collections Chief Curator at Remai Modern. Frater is currently the curator of contemporary art at the Art Gallery of Guelph and the co-director of Artistic Programs at Emerging Curators Institute. As far as her curatorial practice, she is interested in “decolonization, space and place, Black and Caribbean diasporas, photography, art of the everyday, and issues of equity and representation in museological spaces”.

Frater spoke to us at length about how she first was introduced to Thomasos’s work, how she immersed herself in the research and how the exhibition resonates with today’s understandings of systemic racism.

This interview has been condensed for length.

Foyer: When and how did you first encounter Thomasos’s work? What stood out to you then versus what stands out to you now as you’ve undergone the curatorial process and become more familiar not only with her work but with who she was as a person?

Frater: I remember encountering Denyse’s work in passing years ago; I had never met her, but her work made an impression on me. I remember being overwhelmed by it in a way and found it challenging to decipher. As the years went on, I kept thinking about it, especially the ways she used colour and abstraction.

My understanding of her work now is obviously much different than my initial encounter with it. I have more context as a result of reading and researching in-depth for the past two years leading up to the exhibition. I understand it in a completely different way.

The Denyse Thomasos Study Days for the exhibition were illuminating because there was participation from people who knew her, such as Michelle Jacques [co-curator of just beyond], Tim Whiten, Linda Martinello, her former studio assistant, and John Armstrong, her former instructor, to name just a few. They all spoke about the professional circumstances under which they met Denyse and how eventually they came to know her as a friend.

These people speak about Denyse with such fierce loyalty, love and respect which gave me a broader sense of who she was, and how that figured into her work. As someone who is of the Caribbean diaspora, and shared similar experiences to Denyse, I felt a deep sense of obligation in curating this exhibition. It’s a testament to both the artist and the power of her work.

Foyer: The exhibition also includes archival materials like preliminary drawings, never-before-seen footage of the artist in her studio, commentary from those close to her and even personal items like the shoes she wore while painting. What do you hope visitors understand by including these elements of Thomasos’s life and working process?

Frater: Objects that constitute archival materials are often things like letters, photographs or sketches that help to contextualize a body of work. Through them, one can learn about what was informing or influencing an artist. Speaking for myself as one of the curators, I was keen to incorporate those kinds of objects into this exhibition as their inclusion provides visitors with some insight into who Denyse was as an artist and her motivations, beyond simply viewing her art. For example, displayed are excerpts from her journal where she writes about the importance of the grid and how she sees it functioning in her work. Her shoes are covered in layers of paint, built up over the years. They’re sort of these ordinary shoes, but she wore them to create these beautiful, gargantuan paintings. Although I say this as someone who never met her, these kinds of objects help to evoke her presence.

Denyse in her studio with Arc in the background, February 8, 2010. © The Estate of Denyse Thomasos and Olga Korper Gallery, Photo © Nancy Borowick.

Foyer: Along with the use of pattern, scale and repetition, Thomasos employs a distinct and saturated colour palette throughout much of her paintings. Can you tell us more about the reasoning behind her aesthetic choices as it relates to colour?

Frater: In terms of the aesthetics of her colour choices, what I do think is interesting is that while many are struck by how colourful her paintings are, she didn't necessarily consider herself to be particularly proficient as a colourist. Before I started researching her work, I initially read these colours as the colours of the Caribbean. She was very particular about how her paints were mixed as (former studio assistant) Linda Martinello can attest to.

Thomasos did state however that these palettes are specific to each painting and each palette has its own reasoning behind it. With many of the works that she did while she lived in Philadelphia for example, she was informed by the urban landscape of specific city neighbourhoods. There were particular neighbourhoods with derelict houses situated beside houses painted with vibrant colours. She saw that juxtaposition as speaking to this idea of resilience among the ruins. With works that speak to the prison industrial complex, the palettes tie into the fact that a lot of prisons, particularly in prisons that incarcerate men, have adopted these brighter pastel colour palettes in an attempt to influence the behaviour of those who are imprisoned. Pink, for example, is said to have a calming effect on people who are incarcerated.

Denyse Thomasos. Excavations: Courtyards in Surveillance, 2007. Acrylic on canvas, 106.68 x 152.4 cm. From the collection of Bob Harding. © The Estate of Denyse Thomasos and Olga Korper Gallery, Photo: Michael Cullen.

Foyer: What about Thomasos’s work feels most relevant to the world we find ourselves in today?

Frater: Her work certainly seemed prescient. She couldn't necessarily have predicted say the protests of 2020, but she frequently alluded to systemic racism and oppression. The ways in which we view the prison-industrial complex, the ties between our economic systems and the exploitation of Black labour and Black people—all of that is embedded in her work. It seems that we’re just now beginning to dig into these conversations, at least in a “mainstream” sense. Those aspects of her work certainly give it relevancy.

She was speaking about acts that are unspeakable. The horrors of slavery are unspeakable. Language fails us in describing their psychological effects. Prisons often are repressive structures with inhospitable conditions and fail as an antidote to what ails us on a societal level. Yet, the idea of perseverance and resilience is implicit in her work too.

I often feel at a loss for words when I'm trying to speak about how powerful her work is, how all-encompassing it is. If you look at certain elements and structures in her work, there are these openings throughout. Nothing is closed or fixed. I think of those elements as openings for possibility. Much of her work is abstract and when you’re abstracting something you remove it from what it actually is; in a way, she’s dismantling the severity of these acts against Black people.

Michelle Jacques suggested the title just beyond after coming across a quote from artist Julian Kreimer who described Thomasos’s paintings as, and I’m paraphrasing here, ‘just beyond one person’s comprehension.’ He was describing how as a viewer it can be difficult to categorize the kinds of imagery that’s found within these huge canvases with mark-making that extends beyond the surface. Michelle expanded on that description to suggest that there’s hopefulness within her work. That “hopefulness” meaning that the solution to society’s problems could be just beyond us, somewhere in the future. I think that at this point in time when we are facing so many crises, I feel compelled to double down on this idea that things could still change and that we can work towards making them better.

Denyse Thomasos: just beyond is on view at the AGO until February 20, 2023. Pick up your copy of the exhibition catalogue, which includes an essay by Frater, online and in-person at shopAGO.