Dear Denyse

Curator Michelle Jacques shares four letters to Denyse Thomasos, written from curator to artist.

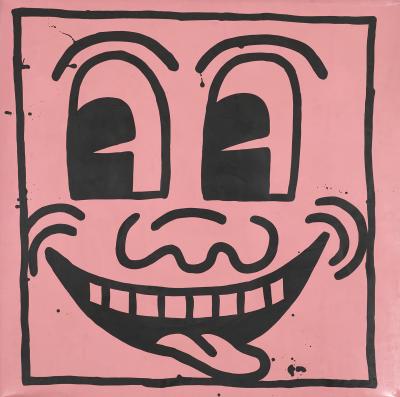

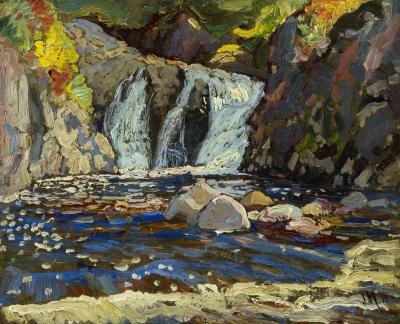

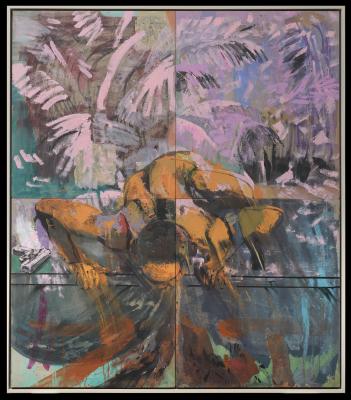

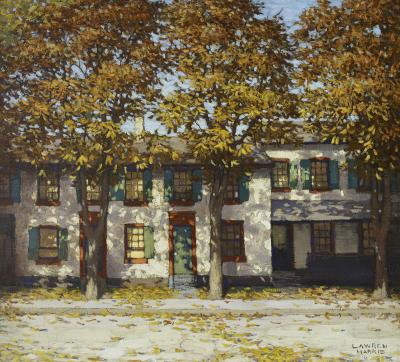

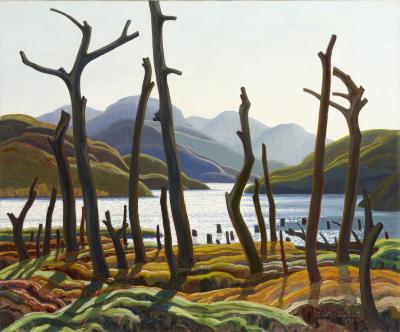

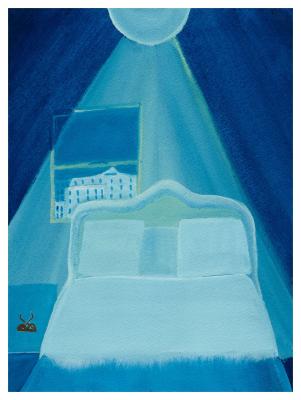

Denyse Thomasos, Untitled (Self-Portrait), 1984-1985. Acrylic on canvas, overall: 121 x 91.5 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of Gail and Gerald Luciano, in memory of Denyse Thomasos, 2022. © The Estate of Denyse Thomasos and Olga Korper Gallery. 2022/27.

Denyse Thomasos: just beyond is an unparalleled exploration into the work of Trinidadian-Canadian artist Denyse Thomasos (1964-2012), heralded as “one of the finest painters to emerge in the 1990s”. Continuing our celebration of the exhibition, we turn our attention to its catalogue, and more specifically, to a series of fictional letters written to the artist. In “Moving Towards Loving Painting Again, or Dear Denyse”, Michelle Jacques, just beyond co-curator and Head of Exhibitions and Collections/Chief Curator at Remai Modern, imagines herself writing to Thomasos throughout her development as a painter, from the early 1990s to the present day. In real life, Jacques and Thomasos did cross paths when Thomasos painted Hybrid Nations (image below) at the AGO as part of Transformation AGO and Jacques was a curator here.

Co-curated by Jacques, Renée van der Avoird and Sally Frater, Denyse Thomasos: just beyond is co-organized by the AGO and Remai Modern in Saskatoon. The catalogue – available for purchase at shopAGO – features contributions by all three just beyond co-curators along with Adrienne Edwards, Marsha Pearce and Denyse Ryner.

Moving Towards Loving Painting Again, or Dear Denyse

By Michelle Jacques, Head of Exhibitions and Collections/Chief Curator, Remai Modern

December 1993

Dear Denyse,

We don’t know each other, but I feel as though we could, there are such parallels in our lives. I’m of Caribbean heritage too—I was born here, but my mother and father are from Guyana and Grenada respectively. Like you, I grew up in the suburban periphery of Toronto. Like you, I gravitated towards studying art—in my case, art history—in university.

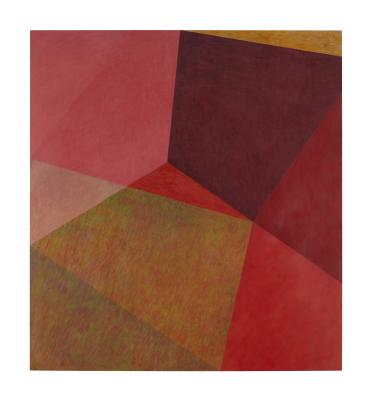

I thought that my background and upbringing had prepared me well for studying art, and particularly for engaging with the colour and rhythms of painting. From the multi-hued houses dotting photographs of Caribbean coastlines and hillsides to the geometric constructions of my upbringing in suburban Toronto, I always felt like I had an eye for colour and composition. Until I recently took a graduate course in art criticism. I felt so alienated from our discussions. I found the insistence on formalist analysis to be almost suffocating in its refusal of my cultural experiences. But your new works—Dos Amigos (Slave Ship), Displaced Burial/Burial at Gorée, and Jail—renew my faith in painting. With these three canvases, you evoke the painful arc that traces the inheritance of all of us who exist on this continent as descendants of enslaved Africans. With these three titles, you have packed your apparently abstract compositions with the significance and ideas that I longed for. How did you conclude that the seemingly innocuous application of monochrome lines of acrylic on canvas was the perfect language with which to explore such profoundly difficult narratives? It was such a relief to encounter your work. I don’t think I could have borne the assumption that good painting must be content-free any longer, an idea that belies the origins of art of the African Diaspora.

Abstraction is central to the aesthetics of African art. There’s a reason that Picasso and the French Modernists looked to it to shake them out of their obsession with depicting their subjects representationally—African art had long been rooted in the conceptual aim of expressing the essences, ideas, values, and powers of its animal, human, and spirit subjects. So, my own inclination is to dive more deeply into the domain of interpretation, no matter how much Greenberg insists that “content is to be dissolved so completely into form that the work of art or literature cannot be reduced in whole or in part to anything not itself.” I rationalize my desire to find narrative, drama, and representation in abstraction by trusting my interest in the multi-modal systems of African art.

Lately, I’ve had a strange idea rolling around in my head. I’ve been asking myself, “What if the turning point in Euro-North American art had been more embracing of the diversiform mediums of African art?” Modernist thought and aesthetics reduce the interdisciplinarity of African culture to two-dimensional images, desired for their usefulness in helping European artists find the reductive flatness of what Greenberg considered the truly avant-garde: “For flatness alone was unique and exclusive to pictorial art.” I have found this understanding of the cross-cultural relationship between African and European art to be impossibly shallow. Abstracted forms painted on canvas couldn’t possibly translate and communicate the complexity of African and Diasporic cultural experiences. Or so I thought before I saw your new paintings.

They are all spectacular, but I think my favourite is Dos Amigos (Slave Ship). Its impenetrable tangle of black lines on white creates such a wonderfully observable and palpable flatness of the composition, but with careful navigation of the intricate interplay of paint sitting on the surface of the canvas, you move us through to the other side of the dense, cross-hatched warren. Such a fantastic, illusory space has been cleverly woven into the plane by your brushstrokes! The barely discernable outline of a boat is apparent in your well-defined and assertive black virgules of paint. Elusive built forms seem to assemble into a particular narrative once they are brought into focus through the lens of the painting’s title. How can I succumb to the modernist dictate that painters eliminate content from their work, when your title—Dos Amigos—infuses the canvas with all the history and horror of the namesake slave ship that transported enslaved Africans to Cuba? Two hundred years after its passage between Africa and the so-called “New World,” with an unassuming palette of black, white, and the greys in between, and a simple, formal vocabulary of gridded latticework, you have created a visual experience that conjures the pressing intensity of a ship’s hold, constructed, as it was, to confine and imprison humans—our ancestors—stolen from Africa. That you have done this with an artistic vocabulary that, throughout the course of high modernist art criticism, is often conjured as an expression of freedom seems to create a tension between subject and medium that holds a message about the innate drive towards liberty that always remains—even in the face of the most unimaginably horrific experiences of bondage and oppression.

You must know how groundbreaking this work is. I wonder if the art world is ready to embrace painting that speaks so directly of such difficult subjects? Your time will come.

With deep admiration,

Michelle

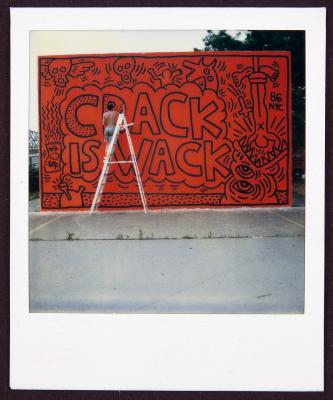

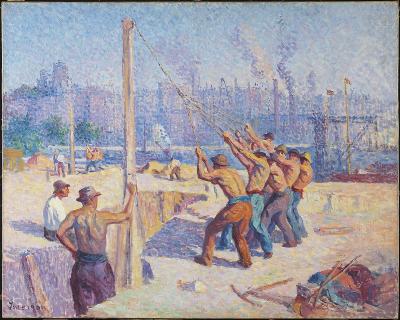

Installation view: Hybrid Nations painted August 3–30, 2005, by Denyse Thomasos, Ben Oakley and Matt Janisse; computer-assisted designs by Joy Charbonneaux (prison cells) and Andrzej Wojaczek (staircase). Latex paint on wall, dimensions variable. Art Gallery of Ontario, Wallworks: Contemporary Artists and Place, May 12, 2005 – Oct 7, 2007. © The Estate of Denyse Thomasos and Olga Korper Gallery, Photo © AGO.

June 2007

Dear Denyse,

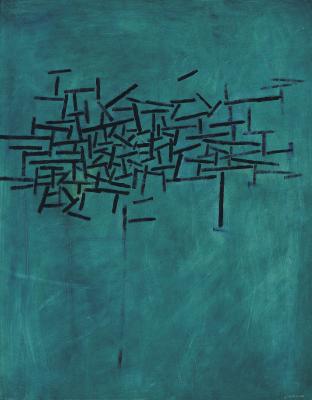

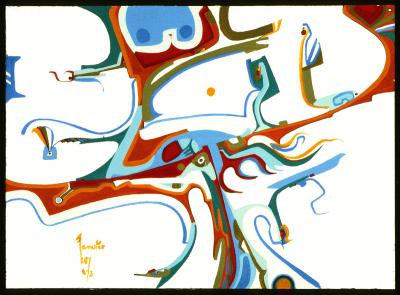

I’m so glad we met when you created Hybrid Nations at the AGO. Now I can write to you not just as a fan but as a friend. Which is not to say that I am any less giddy about your new work as when I was an admiring art history student. Your virtuosic gridwork of ten years ago seemed such an important reclamation of abstraction and allowed for such beautiful demonstration of your astonishing sense of colour that you could have continued on that path for years. But, of course, you pushed forward into new territory. I had the opportunity to see Babylon recently. What a remarkable painting! I see hints of a structure based in the intersecting lines of your past grids, but in this canvas, while you align your vertical strokes in orderly procession across the surface of the canvas, the crosswise marks that would have previously transformed the queue of brushstrokes into a more recognizable grid are gone. Instead, the exchange between surface and pictorial space is articulated through flat, sporadic fields of muted colour along the top and sides of the composition. They seem to sit just behind the crowded and labyrinthine system of brushstrokes, and in concert with that space at the middle, lower section of the canvas, which is devoid of any marks at all, you’ve created a dense matrix. The composite effect of which, perhaps particularly due to the debt owed to the language of graffiti, is a sense of a packed urban space, laden with the infrastructure and energy of a city. You take us to this metropolitan space through largely abstracted visual means, but again, the implication of your title deepens our experience. Biblical allusions recur in your work, so I suspect that is the lens through which you were thinking of Babylon, the ancient Mesopotamian city known for its insurgence, immorality, and denial of one true God. I, on the other hand, couldn’t help but think of Bob Marley’s lyrics when I read your title and saw the imagery. “Open your eyes and look within. Are you satisfied (with the life you’re living)? We know where we’re going; we know where we’re from. We’re leaving Babylon. We’re going to our Father’s land. Exodus: movement of Jah people!” Your painting embraces both references easily, for of course the Holy Bible is the most important book in Rastafari, its pages providing refuge from the corrupted, capitalist, colonial world that its believers equate with Babylon.

I was just reading the interview that you did with Gaëtane Verna for the catalogue for your exhibition Epistrophe, a few years ago at Foreman Art Gallery. It’s so interesting to me that while I needed your work to overcome the alienation that I felt from Abstract Expressionism, you found the sense you yearned for in painting in Willem de Kooning’s work. “The first time I ever saw paintings that made complete sense to me was the…de Kooning show. I saw that de Kooning understood painting so thoroughly that he was communicating through what wasn’t there. He had gone so far in that direction that the communication was contained in the areas that were absent, rather than those that were there, on the painting. That was the first time I realized that what I was trying to do with space and line was valid. Of course, de Kooning wasn’t interested in the same way I am, so that became the puzzle I was interested in solving. I want to use line, space and architectural structures to chart the psychological experience and state of mind at this exact moment of a people with a history of slavery.”

Although de Kooning was a core participant in the Abstract Expressionist movement, the works in Woman, his most famous series, are figurative. Have you ever heard the anecdote of how Greenberg once told de Kooning that “it is impossible today to paint a face,” to which the painter replied, “That’s right, and it’s impossible not to.” While history has painted the Abstract Expressionists as a unified faction of artists who adhered unwaveringly to Greenbergian principles, this exchange reminds me that practice and doctrine are sometimes at odds!

Greenberg believed that modernist painting was rooted in the idea that it would use its own methods to criticize itself, and that through this self-reflexive criticality would emerge a greater expression of competence with the medium. Painting should not bear any of the effects of other artistic modes—no representation, which was the domain of literature, no three-dimensionality, which was the domain of sculpture, and no dramatic effect, which was the domain of theatre. This dogmatic position, of course, negated the modernity of African art and much non-European cultural production, which is so often pan-disciplinary. Is your insistence on infusing your work with narrative, history, architecture, and psychological experience a purposeful challenge to the legacies of Greenbergian art criticism? Intended or not, you have transformed the potential of abstraction in painting and invited me back into an artistic realm that I had felt was unwelcoming to me. I feel myself returning to a relationship with painting, and for that I thank you, Denyse.

With deep gratitude,

Michelle

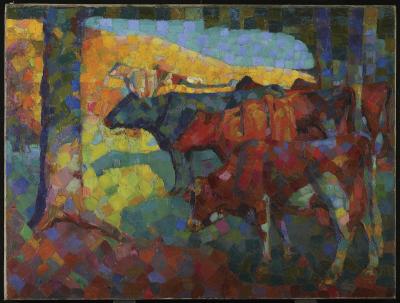

Denyse with Babylon in her NYC Studio, 2005. © The Estate of Denyse Thomasos and Olga Korper Gallery, Photo: The Estate of Denyse Thomasos.

April 2012

Dear Denyse,

How the notion of a boat, which first appeared nearly twenty years ago in the insinuated form of a slave ship in Dos Amigos, has transformed at your hand! I was fascinated to read about your travels, “collecting images of Indigenous architecture and structures including dwellings, bridges, wells, and temples to influence my abstract paintings and to broaden the spatial component in the work. It is wonderful to think of the forms of that vernacular architecture not only as a motivation for your abstracted language, but also as creative structures that embody the same kind of conceptual and spiritual significance as other forms of African art. I wonder if these investigations carried out over the past decade gave you a taste of the absolute freedom that Black folks yearn for thanks to the legacies of enslavement that have inoculated our very being? While I home in on the African sites visited on your travels, in fact, you visited such diverse locations—China, Vietnam, Cambodia, Thailand, Bali, India, Mali, and Peru—and I see them all in these new works. To so many others, the photographs taken during such travels would have been a simple souvenir record of the distinctly beautiful, disparate places; for you they came into focus as new inspiration and seem to have momentously transformed the structural qualities and formal complexity of your work.

Raft takes my breath away! It still has the candour of your more obvious abstractions, but what an image to have taken shape! Your lines coalesce into fully formed, individual structures—each one, I imagine, extrapolated from some building that you captured in photographs during your travel. Or is that too simplistic a read? More likely, the hundreds or thousands of architectural structures witnessed and documented were transformed into ones newly imagined in your mind, vessels laden with historical constraints and future freedoms all at once. The composition amazes me, with its assembly of built elements that result in a Gestalt that reads as some sort of dense environs. Is it a shanty town? A ghetto? A barrio? Whatever the location, it is miraculously transformed from rooted structures into a floating vessel by your ever-adept facility with colour and composition. Out of a reflective, liquid source in the lower foreground of the structure emerges what appears to be the raft of the painting’s title. Individual vessels are organized in a form that culminates in the anterior of a boat as the parts consolidate into a triagonal shape that moves through the space of the canvas from lower left to upper right. The vaporous contour that surrounds three sides of the apparent bow, veiling the complexities of your underpainting and buoying the evocation of the raft, is miraculous. While I am inclined to interpret the structures as water-borne, and the raft as a craft that will take its passengers safely to land, of course, your metaphor must be more layered than a single reading. Last year, your paintings, although similar in content and form to this one, bore titles like Albatross (2010) and Sparrow (2010) and implications of a safer distance from the potential perils of water.

I am forever indebted to you for drawing me back into thinking about painting. I was watching a recording of your talk last year with students at the University of Toronto Mississauga and was interested to hear you say “I never thought of myself as an abstract painter. I thought of myself as a political painter.” Theorists of modern art like Greenberg insisted on such a prescribed and narrow definition of abstraction. You, on the other hand, have married the pictorial and abstract, and used a non-representational vocabulary in an expanded and politically infused manner. Abstraction manifests not only as an image on the surface of the canvas, but as a strategy, a process, a methodology, a way of thinking. Your work is political because the spaces and realms you picture in them are about the African Diasporic experience. Perhaps they include abstraction because that experience has so often been necessarily premised in the visionary, the speculative, and the unrepresentable. The power of your work is its ability to bring to our attention the legacies of slavery, mass incarceration, and—although it might seem facile in the company of these profoundly important subjects—the restriction of Black folks’ entry into the narratives of painting. By refocusing our assumptions about the reconcilability of the political and the avant-garde, and doing it so beautifully, you have debunked Greenberg’s belief that political art is retrograde and aesthetically inferior.10 The contribution you have made to the history of painting is undeniably rare and profound.

With deep reverence,

Michelle

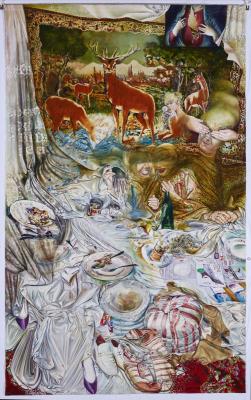

Denyse with Arc, 2009. © The Estate of Denyse Thomasos and Olga Korper Gallery, Photo © Nancy Borowick.

May 2022

Dear Denyse,

It is 10 years since your passing and I’m afraid that the ills of contemporary society have caused the world to catch up to the messages of your work. It is overwhelming to look back over the breadth of your career and to begin to comprehend your contribution to the evolution of painting. You found such a distinct and eloquent language with which to speak about the Black experience and particularly the difficult narratives of slavery and incarceration. During your lifetime, many were not ready to hear what you were trying to tell us. Did it really take the current experience of extreme racial violence and unrest in the United States for the significance of your work to be more fully understood?

Given the impact that living in Philadelphia in the 1990s had on the direction of your work, including your interest in prisons, would you be surprised about the events of the past few years? I am sure the explosion of systemic racism, white supremacy, and far-right militancy in American law enforcement would have come as no surprise to you, as the prison-industrial complex—which you saw as a modern-day form of slavery, a present-day mechanism for confining and controlling Black people and decimating their families and communities—is their necessary corollary. The precisely geometric, circular construction of the high-surveillance prison painted at the centre of Hybrid Nation in 2005 formed such a compelling counterpoint to the unbound, freehand strokes that you added around it. As you yourself have said, “the prisons indicate the complex weave of interdependence between the poor underclass and larger social and economic issues, which I translate in my interweaving lines.” It is remarkable to think that it has been close to twenty years since you painted Hybrid Nations on the wall of the AGO.

How I wish that I had sent you these letters. They are fictions that put into writing the ideas that your painting inspired in me and that continue to grow, even now, thirty years after I first saw your work. I owe you such a debt, Denyse. You transformed the way I think and work as a curator. You created space in painting for those of us who were told it could not hold our histories, interests, or concerns. Thanks to you, painting and I found each other again.

With deep affection,

Michelle

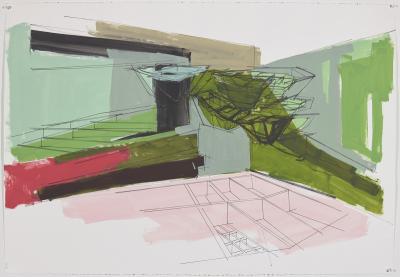

Denyse in her studio, Feb 8, 2010. © The Estate of Denyse Thomasos and Olga Korper Gallery, Photo © Nancy Borowick.

![Keith Haring in a Top Hat [Self-Portrait], (1989)](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-11/KHA-1626_representation_19435_original-Web%20and%20Standard%20PowerPoint.jpg?itok=MJgd2FZP)