Norman McLaren moves audiences on stage and canvas

Curator Georgiana Uhlyarik and choreographer Guillaume Côté discuss the filmmaker’s artistry.

Norman McLaren. White Birds, 1945. Oil on canvas, Overall 46 x 33.6 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Gift of Eugene (Jack) Kash 1912 - 2004, 2004. © Norman McLaren Estate

An Academy Award-winning filmmaker whose pioneering advancements in animation influenced generations, Scottish-Canadian artist Norman McLaren (1914-1987) was an incredibly multifaceted human - whose creative energies found expression in dance, composition, teaching, pacifism and visual art.

His artistry shines this month in Toronto, as his painting White Birds goes on view in the J.S. MacLean Centre for Indigenous & Canadian Art at the AGO, at the same moment, the lights go up at the Four Seasons Centre on Frame by Frame, a ballet inspired by the life and art of McLaren. Created by legendary theatre director Robert Lepage and gifted choreographer Guillaume Côté, the ballet debuted in Toronto in 2018 and now makes its triumphant return.

Painted in the last year of World War Two, White Birds is an emotional and abstract response to the chaos and cacophony of war and a hope for peace. It was also ahead of its time - engaging with abstract visual vocabulary as only few artists were doing then in Toronto and Montreal. Generously gifted to the AGO, by early McLaren musical collaborator Eugene (Jack) Kash, it was recently treated by AGO conservators and now reverberates brighter than ever.

To celebrate this McLaren moment in Toronto, we connected the AGO’s Frederik S. Eaton Curator of Canadian Art, Georgiana Uhlyarik, with Frame by Frame choreographer Guillaume Côté to discuss how they came to his art, about the tension between abstraction and the figurative, and of course, Romanian folk music.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

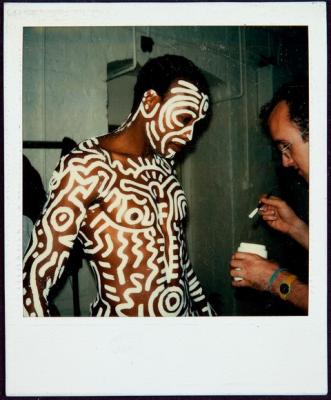

Harrison James and Heather Ogden in Frame by Frame. Photo by Karolina Kuras. Courtesy of The National Ballet of Canada.

Uhlyarik: My introduction to McLaren came at the AGO, early in my career, when White Birds was gifted to the Collection. I remember being deeply impressed by this giant of the Canadian imagination. How did you come to Norman McLaren?

Côté: I had a close friend who studied the history of art in Montreal, and he sent me many of his films. In his loops and abstract works, there is always the element of choreography. I admired how he crafted musical shapes moving through an abstract world. I also had seen his dance films, and I made a film called Lost in Motion, influenced by his iconic film Ballet Adagio (1972), made with dancers David and Anna Marie Holmes. It is a slow-motion study of the pas de deux adagio, one of the most exacting dances of classical ballet. To me it was just mesmerizing. Robert Lepage and I had been talking about how to bring that to life on the stage. I think dance is the best, best way to do so. When we began to dig in, I started seeing McLaren’s range as a human being. From doing all these abstract animations, to drawing directly on film, to arranging paper cutouts, to stop motion - his tenacity is mind boggling. His work process was fascinating to me because it was very much like ballet in a sense that it was all about perfectionism.

Uhlyarik: Like McLaren, Alma Duncan (1917-2004) was a Canadian modern painter who had a full-time career at the NFB (National Film Board of Canada). For her and many others, it was a beautiful way in which she and other artists could support themselves, and expand their creative range. Often in Canada, we are slow in honouring those who came before and the responsibility they gave us to carry things forward. Would you agree?

Côté: Absolutely. I could not agree more. I think we need to celebrate also. I think a very, very quick and easy thing to do is to forget and move on. I am very proud this is a Canadian production, with all Canadian talent and artists.

Uhlyarik: In my role as a curator, I think a lot about the tension between representation and what we call abstract. I am interested that McLaren made a completely abstract painting but titled it something completely identifiable, White Birds. I think about that tension in ballet – how it locates abstract music and movement, in the most embodied way possible, through the human figure. How do you think about these forms?

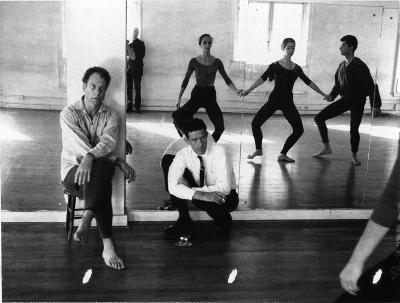

Guillaume Côté and Robert Lepage in rehearsal for Frame by Frame. Photo by Elias Djemil-Matassov. Courtesy of The National Ballet of Canada.

Côté: We developed this project over five years. The first workshops were very much just exploring the material and his films. We learned the exact choreography of his films and transposed pieces of it directly onto the stage as a starting point. The challenge was how to incorporate the various biographical scenes. To get to your point of the abstract and the power of dance, it was about figuring out how to explore his ideas about the power of lines while marking someone's lived experience. Vertical and horizontal lines are the root of the films he made, and that led me to explore how to bring stop-motion technology to life with human bodies. It’s been five years since we debuted this work, and coming back to it now, these abstract moments are the ones we wanted to lengthen. Our research and workshopping resulted in McLaren influencing our own approach to the work.

Uhlyarik: There's a long history between dance and cinema, but what you've done with this project is the reverse: you’ve taken dance that only existed on film, and created a public performance. Correct?

Côté: Yes. But it’s important to remember that at the time he was creating his films, the effects couldn’t have been performed live. Until now. And we’re able to add other elements to it, which makes it surprising and powerful. I'm thinking of a scene where McLaren’s looking through a camera, at the back of the stage, filming a dancer, and then he has a paintbrush, and then the paintbrush choreographs the entire thing. And then the figure is projected onto the backdrop, and it looks like he's painting the live dancer onto the backdrop. And then, once we're in that scene, we transition right into politics, using the visual effects that McLaren had himself created. We were careful about how to bring his film craft to life and achieved it by adding elements of stage poetry and stage craft.

Uhlyarik: I’m Romanian and was delighted by the use of the pan flute (which is the most Romanian instrument you can have) in Pas de deux (1968), McLaren’s collaboration with composer Maurice Blackburn. The music is performed by Dobre Constantin and the United Folk Orchestra Romania! Do we know where that musical inspiration comes from?

Côté: In his films, for sure, that is very much the work of composer Maurice Blackburn. So brave. Can you imagine, during that time, creating a 14-minute drone? Those sounds are very melodic in many ways, not unlike trance music in a contemporary nightclub. But that was so ahead of its time in so many ways. That must have been so bizarre when it first came out. That music, to me, is absolute genius.

McLaren as a composer, we do touch on that. Did you know he is also considered the first person to create electronic music? Because in drawing directly on the filmstrips, he created sounds - these blips and bleeps, which he incorporated into the final. I hated these blips and bleeps when I first started working because they sound very old-fashioned, like something from the Alien soundtrack. But once you understand what they are and how he composed music for his visuals, it’s pretty great.

Artists of the Ballet in Frame by Frame. Photo by Karolina Kuras. Courtesy of The National Ballet of Canada.

White Birds is on view on Level 2 of the AGO in the Molly & George Gilmour Gallery in the J.S. McLean Centre for Indigenous & Canadian Art (gallery 233).

Frame By Frame is a collaboration between The National Ballet of Canada, Ex Machina and the National Film Board of Canada. Performances run June 2 to 11, 2023.