Sarindar’s influence

Artists Rajni Perera and Pamila Matharu reflect on their deep reverence for Sarindar Dhaliwal

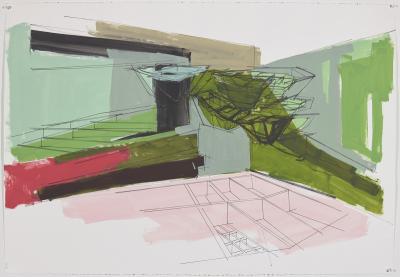

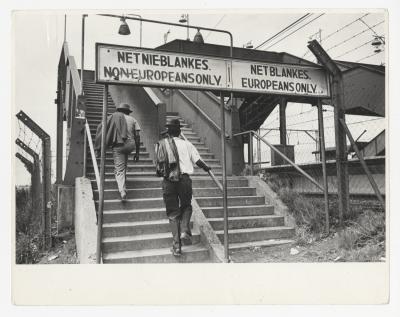

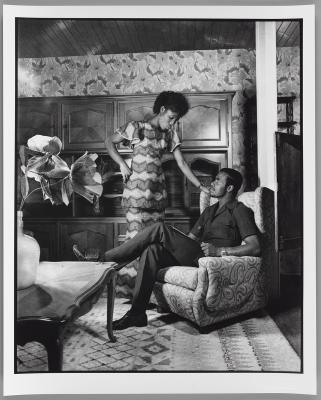

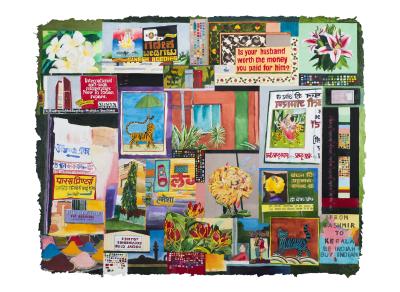

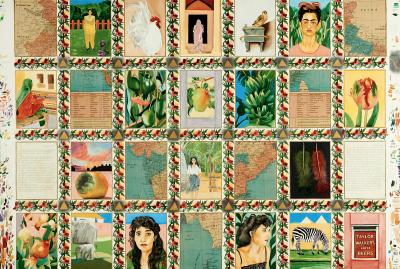

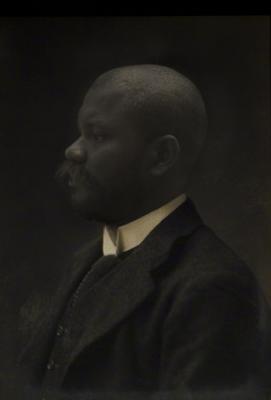

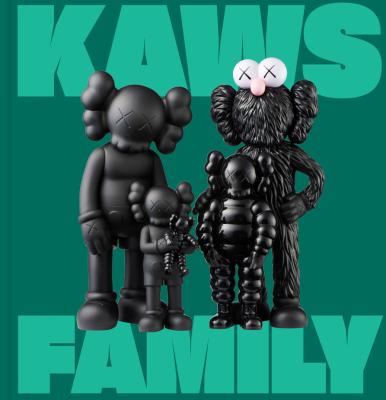

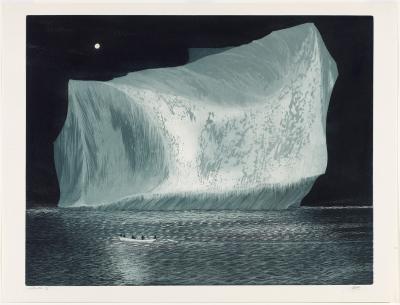

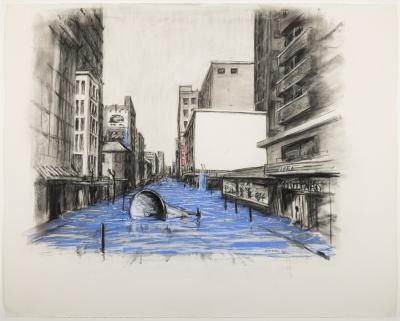

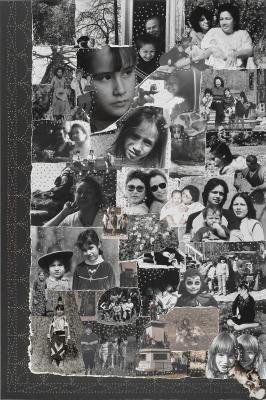

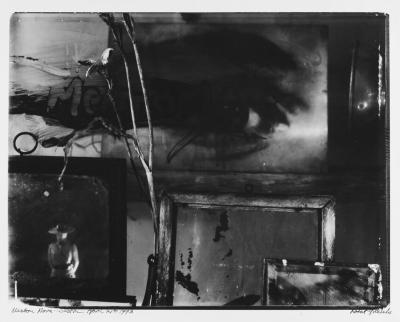

Sarindar Dhaliwal. Oscar and the Two Fridas, 1991. Mixed media on paper, Overall: 50 × 60 cm. Agnes Etherington Art Centre, Queen's University, Kingston. Gift of Carole Patry and Michael Edwards, 2007 (50 - 020).

Since opening at the AGO in July, Sarindar Dhaliwal’s solo exhibition When I grow up I want to be a namer of paint colours has invited visitors on a whimsical, surreal journey exploring memory, migration and identity. While new fans and admirers of Dhaliwal’s groundbreaking work are created each day through the exhibition, many have counted her as a favourite artist and major inspiration for years.

Toronto-based contemporary artists Rajni Perera and Pamila Matharu consider themselves students of Dhaliwal’s, both in the figurative and literal sense. They first encountered her work roughly a decade ago – Perera as Dhaliwal’s pupil at OCAD and Matharu as an attendee to the opening of her 2013 solo exhibition at A Space Gallery. Her mentorship, impact and influence are evident in both artist’s practices, illustrating Dhaliwal’s enduring position as an influential figure in Canadian contemporary art.

After experiencing When I grow up I want to be a namer of paint colours Perera and Matharu shared with Foyer their candid reflections about how they first encountered Dhaliwal, their deep reverence for her work, and their thoughts about her solo AGO exhibition.

By Rajni Perera

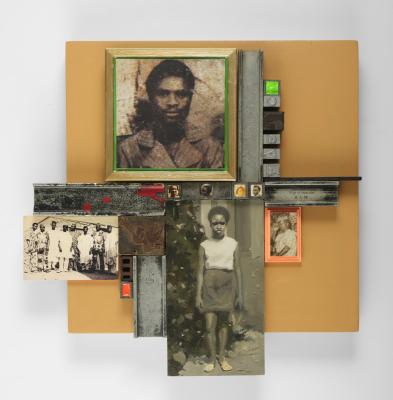

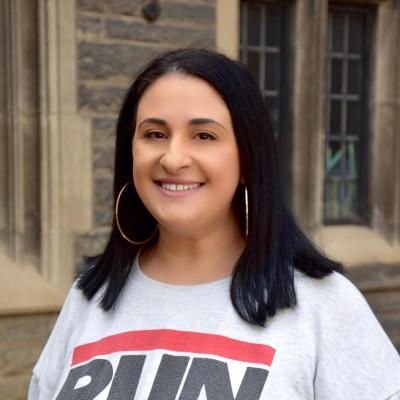

Rajni Perera. Photo by Dimitri Levanoff.

I met Sarindar during my second year of OCAD. At the time, there were two profs of colour in the Fine Arts department. Around the same time, ‘the orient and the occident’ was used to describe my work during class critiques by white faculty, and the entirety of African and Indian art history was offensively crammed into a single course. I was unacquainted with her work before then, and was beginning to form my own varied cannon as a diasporic artist, moving through different styles and aesthetics to see what worked for me; telling stories about feeling cornered and othered in my work. She carefully and kindly told be about moving through clichés in my work to get to the other side. I hold that advice to this day, as it rings so true within this strange time of trying to wiggle from the grasp of the institutional expectation of ‘identity performance’, which diasporic artists are so plagued with and bored by. When you are honest about the intersections occurring within your own identity and expression, what blooms is a valuable truth about yourself and your work by proxy, as ‘When I grow up, I want to be a namer of paint colours proves so wonderfully and rigorously.

What strikes me about the exhibition is the inspired approach, throughout the chronology of Sarindar’s work, of speaking about her immigrant life through the lens of confabulation, daydreaming, and ‘fairy stories’. In the same way that white lies and tall tales are told, exaggeration and embellishment form a stage where ugly and difficult pasts can be understood through a candy-coated glaze of narrative technique. In this way, she hypnotizes us into understanding. The British nursery rhymes floating in the foreground of olive, almond and mustard (2010) form a familiar sticky-sweet coating atop the video work, describing a politically and personally alienating, traditional technique of oil-based POC hair care administered in her youth in Southall by her mother, ironically now appropriated heavily in the west. In Oscar and the Two Fridas (1991) [image at top] we see Sarindar dream of a fictional meeting of the writer Oscar Wilde and artist Frida Kahlo, with whom she finds a kinship in their distinct mechanism of ‘turning ugliness into something transcendent’, something I would argue is also a coping mechanism. So much can be said about diasporic art practices acting as a window for others to understand, while retaining certain therapeutic functions for the artists themselves in solving the memories of their pasts, fragmented situations, and feelings of uncertainty and displacement so common and distinct to the lives of immigrants in general. It’s very important that this aspect be regarded as separate from a telescope made for institutions and the white gaze on othered lives. I like to think that this function is made by us and for us.

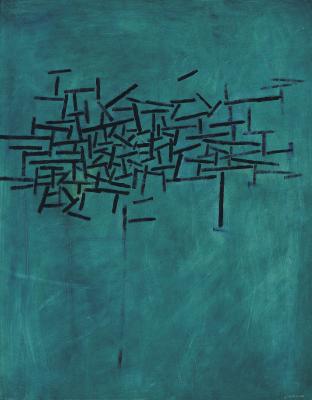

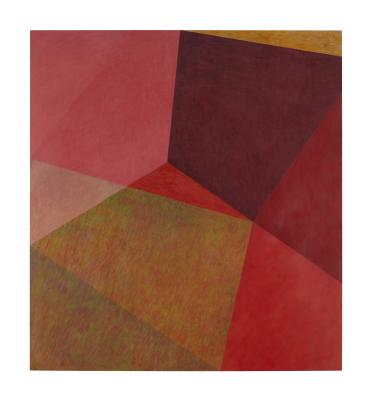

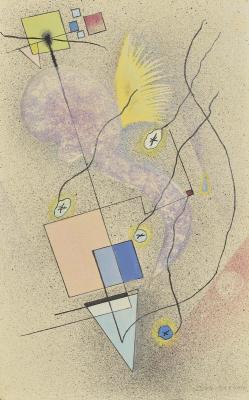

Sarindar also turns to aesthetics as an agent of transmutation. As she works through a list/category grid-based composition in the painted works, which she explains are attributed to not being taught Western perspective painting, simultaneously there is a brilliant, joyful command of exuberant colour throughout the painted works in a peculiarly hybridized ‘personal catalogue’ composition style. It makes you wonder if within the rigid and objectifying visual format of categorization, the element of colourful beauty becomes a ‘rewilding’ effort or even an effort of reconciliation, even if this may be a habit owing to Sarindar’s own ways. In her words, “I do not want to sacrifice politics for beauty, but to engage one through the other” and I do feel that there is an earnest and profound search to connect parts of the artists’ self that are nurtured into sorting, organizing and researching, and her simultaneous inclination to wildly live and remember.

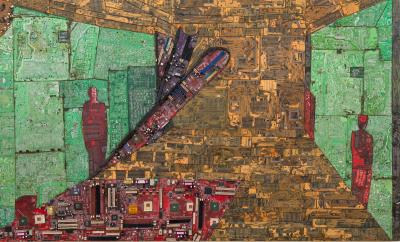

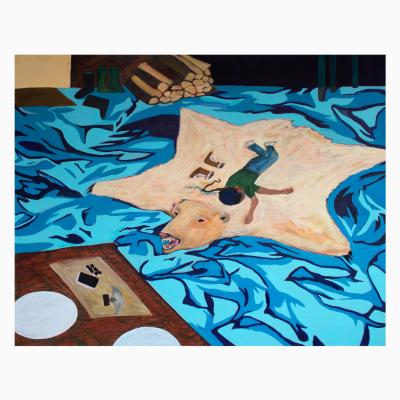

Rajni Perera was born in Sri Lanka in 1985 and lives and works in Toronto. She explores issues of hybridity, futurity, ancestorship, migrant and marginalized identities/cultures, monsters and dream worlds. These themes come together to fuel explorations within a multimedia practice that includes drawing and painting, clay, wood, lanterns, new media sculpture, textile, and most recently, synthetic taxidermy. Perera seeks to open and reveal the dynamism of the icons, beings and objects she creates by means of a subversive aesthetic that counteracts antiquated, oppressive discourse, and acts as a restorative force.

By Pamila Matharu

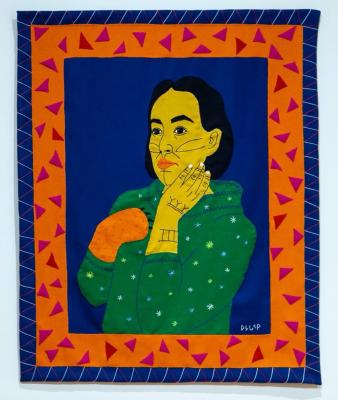

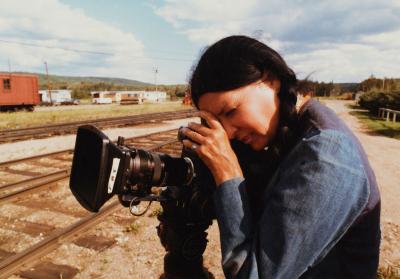

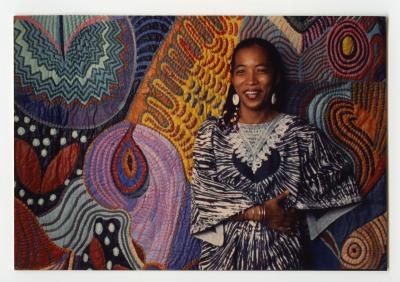

Pamila Matharu. Image courtesy of Pamila Matharu

Marigolds were the bane of my existence growing up in suburban Willowdale, behind Lauraleaf Plaza. After arriving in Rexdale from Birmingham, UK in 1976, we moved from Rexdale to Concord. Then in 1984, when I was 11 and my elder brother Tony was 14, we arrived in Willowdale. On May 24 weekend aka the start of gardening season (and cottage season for others), my mother Surinder, would haul Tony (aka Kanwaljit), and me off to the garden centres.. My name is Pamila, with an “i”. I wasn’t given a Panjabi Sikh name. Mine was riffed off the many variegated Pamelas that existed in the world, but with an Indian spelling that – my father would always profess – sticks it to the English! Back to the garden centre. I would traipse the rows and rows of flowers, taking in the visual feast of colours - tulips, dahlias, and roses. After we would grab bags and bags of gardening soil, it would be time to pour into the marigold section. I started to despise these marigolds year after year; yellow, orange, red, variegated, marigolds. Tony was always eager to pick everything up and get back to whatever sports game he was glued to on the family room telly. He was never commanded to do a lot of chores or outdoor duties as he was the cherished son. I being the younger, and the daughter, perhaps was perceived to be domesticated for a future life as a ‘wifely homemaker’.

On January 18, 2013, I walked into the opening reception of Sarindar Dhaliwal’s solo exhibition at the stalwart artist-run centre, A Space Gallery in downtown Toronto. When I turned the corner of the entrance, I was faced with a freshly produced image by Sarindar: a map of my Motherland titled, the cartographer’s mistake: the Radcliffe Line (2012)Cyril Radcliffe was the lawyer who demarcated my homelands, Sarindar explained on opening night. I could feel the blood rushing from the top of my head to the bottom of my feet. I had a very moving, visceral response to this work; I didn’t know in the moment of initially seeing it, whether I should laugh or cry. All the years haggling with Mama about my dislike of marigolds melted within seconds into minutes into hours, I could not peel my eyes off these flowers. Every fibre of my being wanted to run to Mama and hug and hold her so hard and apologize for not understanding her, it was like we were lost in translation all those years, but that opening night, in that moment of seeing Sarindar’s artwork, finally found. I came home that evening and looked at my walls long and hard. I knew in my body, mind and spirit that I was going to give that artwork a home; hence I pestered Sarindar for a couple of years to acquire it, and I happily told her I wanted to purchase it! I acquired the 1st edition in 2016. I still haven’t experienced cottaging, but I’ve got a lil’ piece of home always with me thanks to Sarindar.

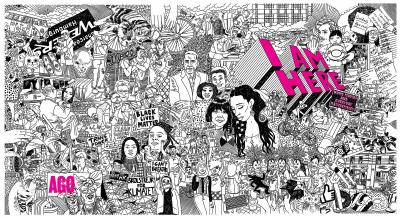

Pamila Matharu is an immigrant-settler of north Indian Panjabi-Sikh descent, born in Birmingham, England, based in Tkarón:to (Toronto). As an artist, they explore a range of transdisciplinary feminist issues, blurring the lines between objects, activism, community organizing, and public pedagogies. Their practices include object making (installation, collage, film/video/photography), curating/organizing, artist-led teaching, arts advocacy, and social practice.

When I grow up I want to be a namer of paint colours is on view now at the AGO on Level 1 in the Philip B. Lind Gallery (131 & 132).