Six Elements of The Culture

Explore the six distinct sections that make up the landmark hip hop exhibition The Culture

Installation view, The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century, December 6, 2024 to April 6, 2025. Art Gallery of Ontario. Artwork in foreground: Aaron Fowler. Live Culture Force 1's, 2022 © Aaron Fowler. Photo © AGO

The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century is the first exhibition of its kind. It highlights hip hop’s ongoing influence on the modern zeitgeist by placing fashion, consumer marketing, music and objects in dialogue with paintings, sculpture, photography and installation. In short, the exhibition illustrates how hip hop culture permeates pop culture at large and shapes the work of many contemporary artists.

As visitors enter The Culture, they will embark on a journey that transcends eras and artistic mediums. Arranged by six thematic sections, the exhibition presents a complex picture of hip hop’s impact, prompting reflections of activism and racial identity, notions of bling and swagger, as well as gender, sexuality and feminism.

The Culture is on view at the AGO until April 6. Get more acquainted with the themes that situate this dynamic mix of artworks and objects and take a closer look at a selected work from each section.

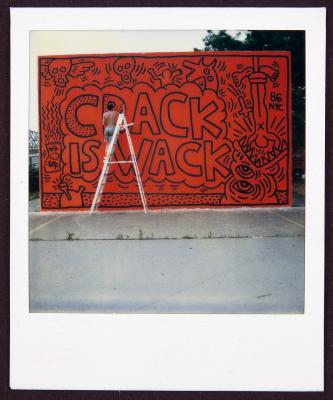

Language

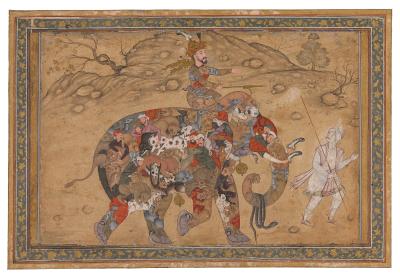

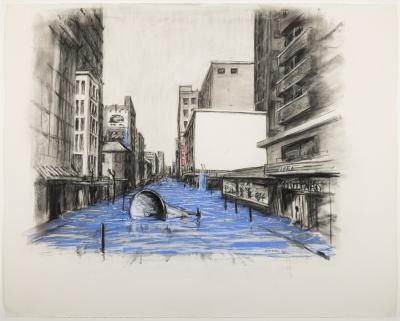

Hip hop is an art-form about language: the visual language of graffiti, a musical language that includes scratching and sampling, and the written and spoken word. Call-and-response chants and rap lyrics overlaid on tracks, are the foundations of hip-hop music. In addition to the poetry, one of the most recognizable markers of hip hop is graffiti. Since the 1970s, graffiti writers have coloured city trains, overpasses, and walls with spray paint. Many graffiti writers sign their works with recognizable tags. Some messages are meant for anyone to understand, while others are coded in references, technologies, or forms that require insider knowledge, asserting the right not to be universally understood.

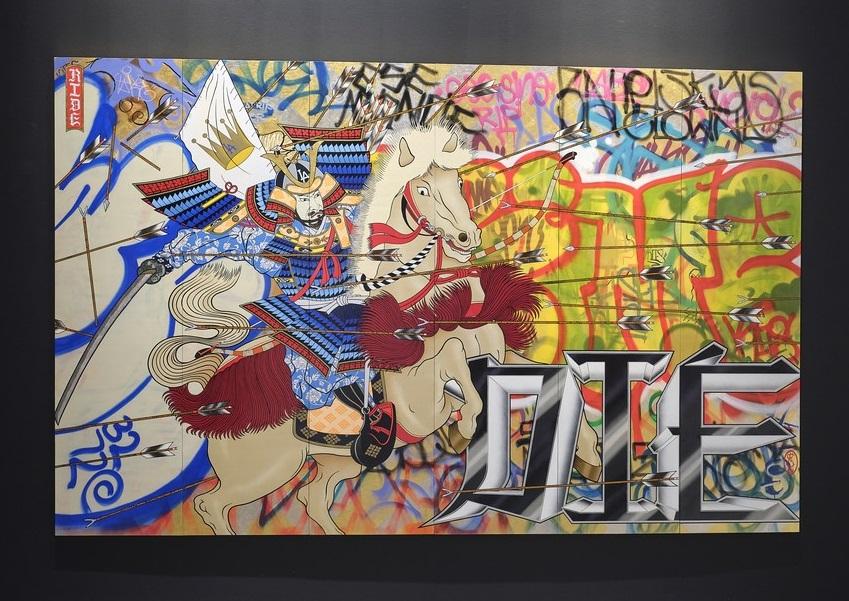

Installation view, Gajin Fujita. Ride or Die, 2005. Spray paint, paint marker, paint stick, gold and white gold leaf on wood, 213.4 × 336.6 cm. Collection of the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, Missouri, Bebe and Crosby Kemper Collection, Museum purchase, Enid and Crosby Kemper and William T. Kemper Acquisition Fund, 2005.39.01. © Gajin Fujita, courtesy Buchmann Galerie Berlin. Photo: AGO.

A central artwork in The Culture’s Language section, Ride of Die (2005) is a large mixed media work that utilizes spray paint, paint stick and gold leaf on wood panels. Los Angeles-based artist Gajin Fujita often combines historic Japanese art with the visual language of LA street culture. In works like Ride or Die, the result serves as a unique mode of activism and free-form creative expression.

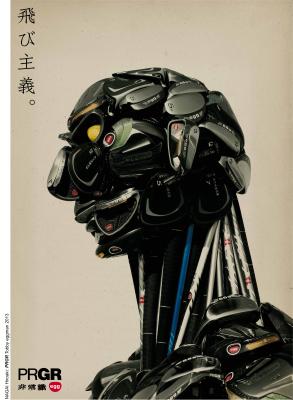

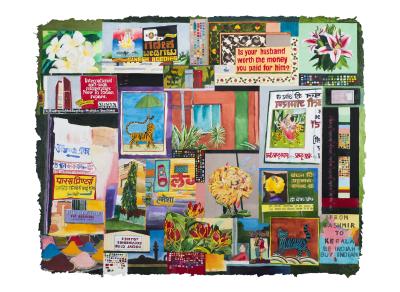

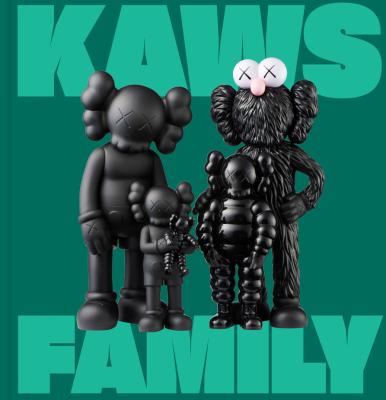

Brand

In this section, the concept of a brand is explored as more than marketing commercial goods. It extends to the ways an individual uses communication technologies to position themselves in the public sphere. In previous decades, hip hop artists functioned as unofficial promoters of major fashion brands aligned with their style and public personae. Today, artists often partner with companies or create their own independent brands. Whether designing fashion, recording music, or making art, artists blur the boundaries between these art forms, between being in business and being the business.

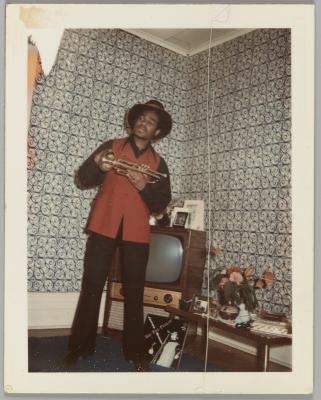

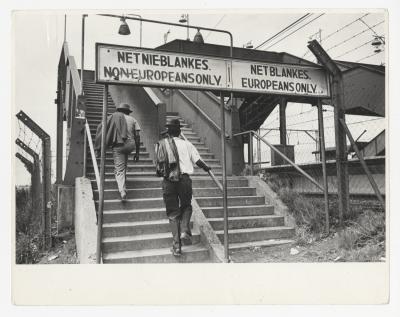

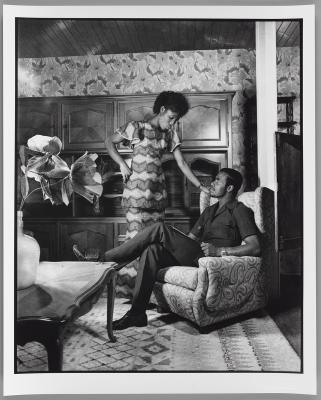

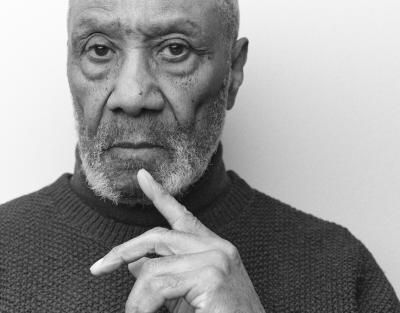

Zanele Muholi. Kalmplex, Toronto, 2008. Gelatin silver print, 74.9 × 49.5 cm. Courtesy of Dr. Kenneth Montague | The Wedge Collection, Toronto. © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of the artist and Yancey Richardson, New York

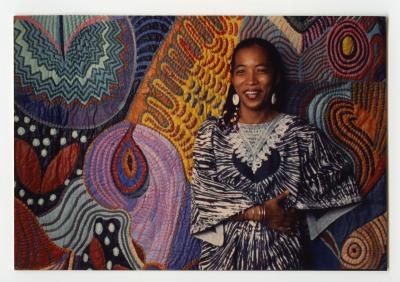

In 2008, South African artist Zanele Muhoi visited Toronto to shoot portraits for her ongoing photography series Faces and Phases. The series reflects the artist’s commitment to uplift Black queer communities in post-apartheid South Africa and beyond. In the Brand section, visitors will encounter a portrait by Muhoi featuring Toronto multimedia artist Kalmplex, who is well known for their presence in the city’s art and music scenes. Kalmplex wears a baseball Jersey by legendary Toronto streetwear brand Too Black Guys.

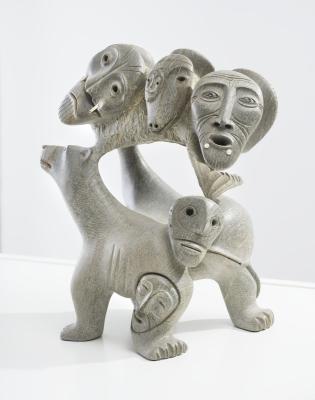

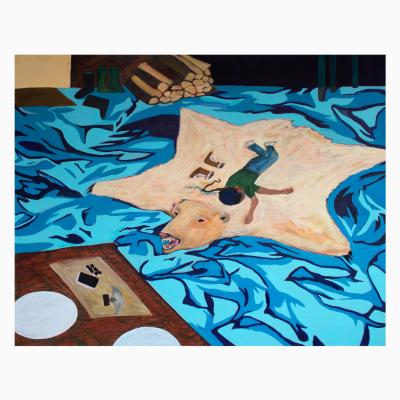

Adornment

While style often signifies class and politics, few subcultures are as self-referential or as influential as hip hop. Reaching back from Big Daddy Kane’s layers of gold chains to Lil’ Kim’s technicolour wigs, this section celebrates some of the most important, enduring, and distinct looks in pop culture, and how they originate with hip-hop. Jewellery flashes, grills glint, and iconic Air Force 1 sneakers are meant to be seen.

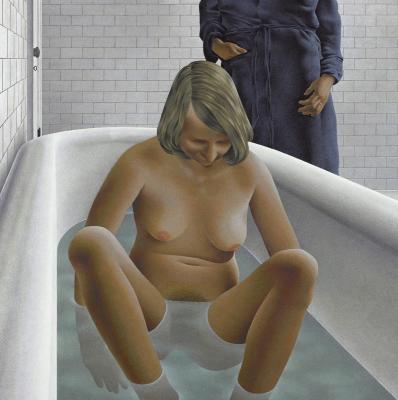

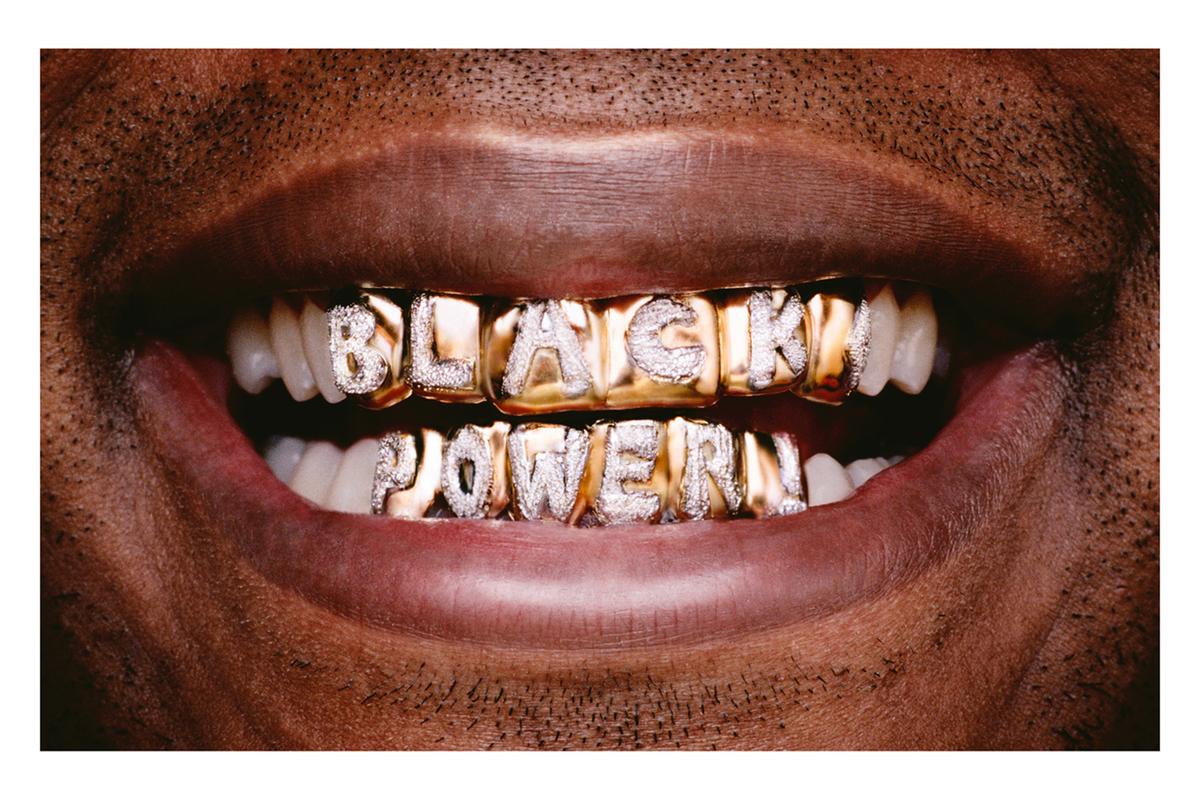

Hank Willis Thomas, Black Power, 2008. Lightjet print, 62.2 x 100.3 cm. © Hank Willis Thomas. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

Found in the adornment section, this photographic work by acclaimed artist Hank Willis Thomas frames the teeth of a Black man wearing a gold grill on which the words “Black Power” are encrusted in silver. Like many of Thomas’s works, Black Power (2006) grapples with issues of grief and addresses the commodification of Black male identity by raising questions around visual culture and African American representation.

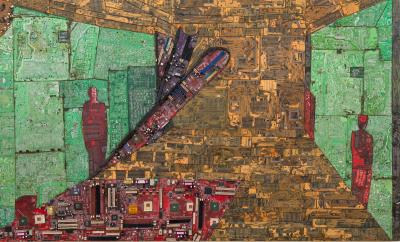

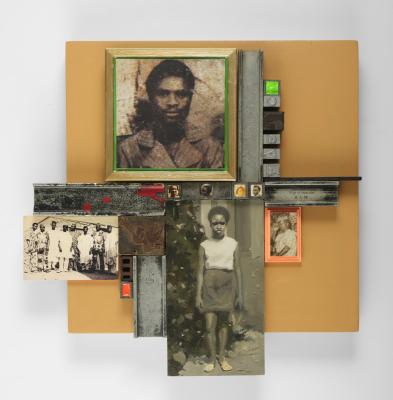

Ascension

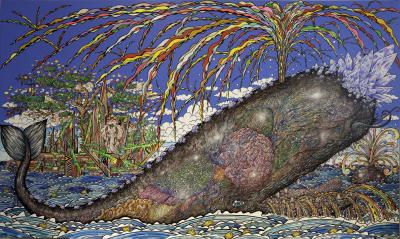

Death—or the spectre of it—along with notions of ascension and the afterlife frequently appear in hip hop lyrics. Inspired by themes of ascent in the culture, artists featured in the Ascension section create works that invite reflection. Ordinary objects transform into altars and monuments, and images of Black bodies melt into heavenly clouds. Hip hop is a cultural form that artists use to process, self-reflect, lament, grieve, or remember those lost.

This 2008 painting by Houston-based artist El Franco Lee II depicts the late DJ Screw presiding over his turntables at his home surrounded by friends and fans. DJ Screw in Heaven pays homage to the legendary DJ and producer who created Houston’s iconic “chopped and screwed” sound.

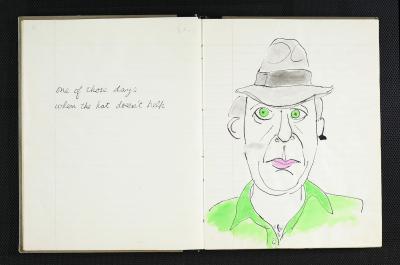

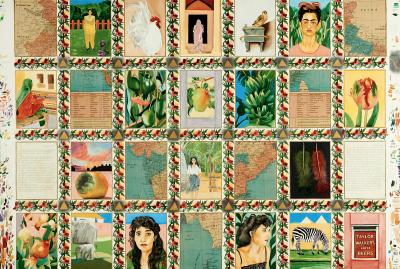

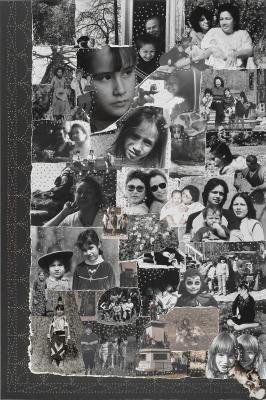

Tribute

From name-dropping in a song to wearing a portrait of a deceased rapper on a T-shirt, The Culture’s Tribute section illustrates that respect and shoutouts are fundamental to hip hop culture. These references help proclaim influence, honour legacies and create networks of artistic associations. Hip hop as a global artform has become a touchstone for artists of the 21st century. As visual artists trace hip-hop’s conceptual and social lineage through tribute, they engage the idea that the art historical canon, previously homogenous, white, and stable, is fluid depending on your own background and preferences, questioning what is beautiful, who is iconic, and whose histories are valued.

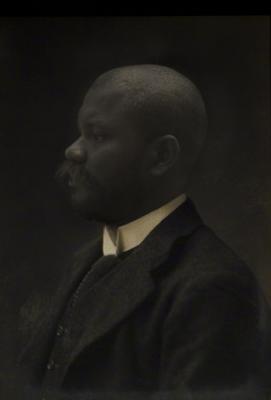

Carrie Mae Weems. Anointed, 2017. Archival pigment print, 181.6 × 120.7 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery. © Carrie Mae Weems.

In this 2017 portrait commissioned by W Magazine, renowned artist Carrie Mae Weems bestows honour on the “Queen of Hip Hop Soul” Mary J. Blige. Cast in fiery red, the side profile portrait features Blige receiving a crown, placing her in the lineage of other Black women icons.

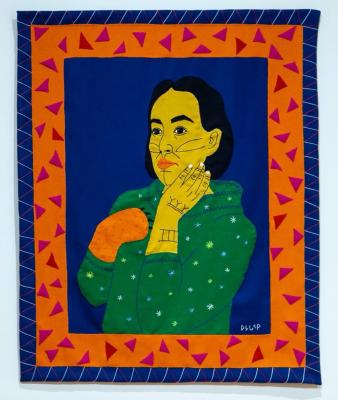

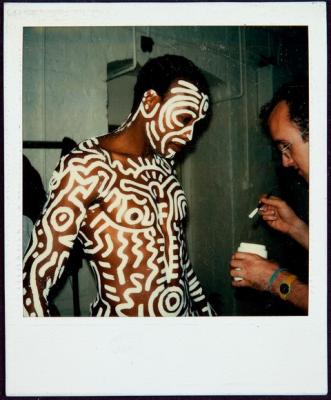

Pose

From the club to backyards and bedrooms, from online to the street and the stage, the works in this section explore what one’s gestures, stance and mode of presentation can communicate to others. Here, artists explore and explode stereotypes of gender and race, examine the line between appreciation and appropriation, consider the relationship between audience and performer, and ask which bodies are considered dangerous or vulnerable—and who decides.

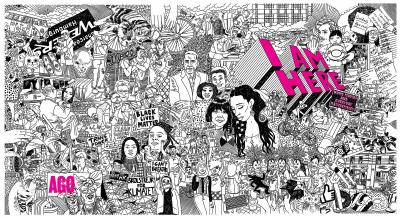

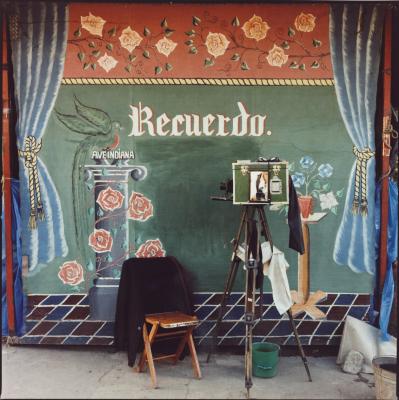

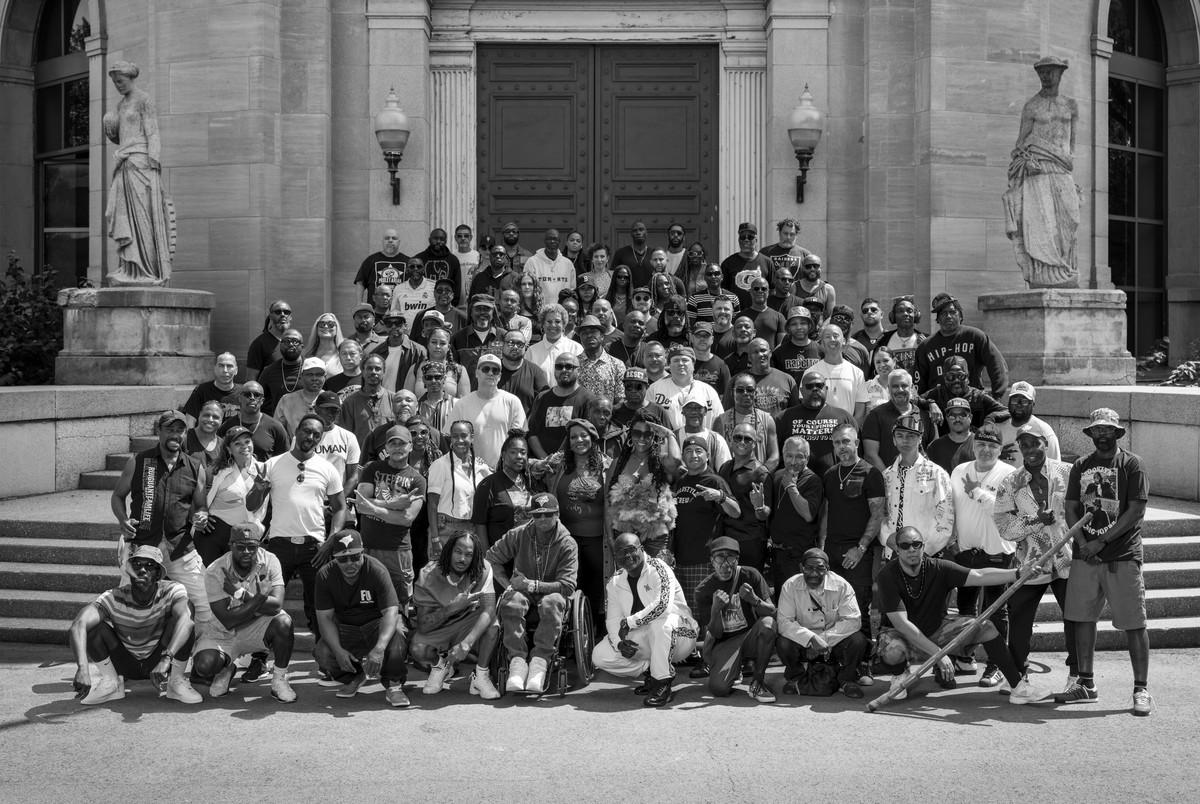

Patrick Nichols. A Great Day in Toronto Hip Hop, 2024. Inkjet print, Overall: 147.3 × 223.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Patrick Nichols

On view in the Pose section, A Great Day in Toronto Hip Hop is the centerpiece and closer of the Toronto iteration of The Culture. On August 14, 2024, Canadian photographer Patrick Nichols and historian Francesca D'Amico-Cuthbert gathered 103 key figures from three decades of Toronto hip hop for a massive group portrait on the steps of the Toronto heritage building, The Liberty Grand.

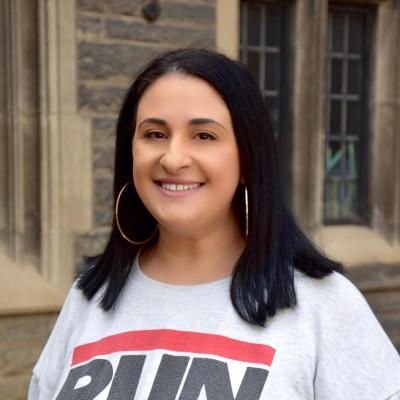

The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century is currently on view on Level 5 of the AGO. The exhibition is co-curated by Asma Naeem, the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA)’s Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director; Gamynne Guillotte, the BMA’s Chief Education Officer; Hannah Klemm, Saint Louis Art Museum (SLAM)’s Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art; and Andréa Purnell, SLAM’s Audience Development Manager. The AGO presentation is organized by Julie Crooks, Curator, Arts of Global Africa and the Diaspora, AGO.