Words by asinnajaq & Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill

Two of the featured artists in We Are Story offer environmental insight.

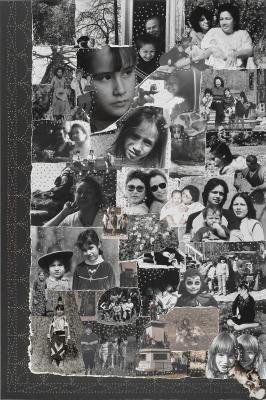

asinnajaq, where you go i follow, 2020. Inkjet print on poly-sheer fabric and vinyl lettering. Overall: 246.4 x 304.8 cm. Purchase, with funds from the Canada Now Photography Acquisition Initiative, Edward Burtynsky and Nicholas Metivier, 2021. © asinnajaq. Photo courtesy The Shell Projects.

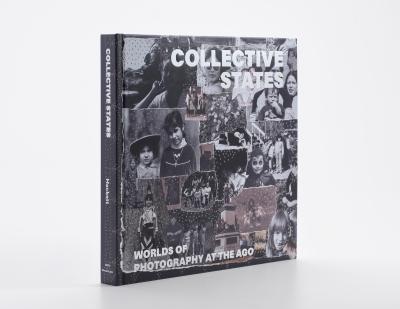

Since January 2023, the group exhibition We Are Story: The Canada Now Photography Acquisition has been on view at the AGO (128, The Edmond G. Odette Family Gallery, and 129 The Robert & Cheryl McEwen Gallery), showcasing the vitality and range of contemporary Canadian photography. Featuring recent works by asinnajaq, Raymond Boisjoly, Aaron Jones, Lotus Laurie Kang, Robert Kautuk, Gabrielle L'Hirondelle Hill, Sanaz Mazinani, Jalani Morgan, Louie Palu and Dawit L. Petros, this exhibition is curated by AGO Curatorial Fellow Marina Dumont-Gauthier with Sophie Hackett, AGO Curator, Photography.

asinnajaq is an Inuk multidisciplinary artist, filmmaker, writer and curator from Inukjuak, Nunavik. As the daughter of celebrated filmmaker Jobie Weetaluktuk and Professor Carol Rowan, she grew up immersed in storytelling. Throughout her multidisciplinary practice, asinnajaq weaves together narratives of land, water and Inuit histories. She advocates for the environment, engaging with local communities and disseminating Inuit culture through art.

Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill is a Métis artist exploring the history of found materials, and enquiring into concepts of land, property and economy. Often, her projects emerge from an interest in capitalism as an imposed, impermanent and vulnerable system, as well as in alternative economic modes. Her works have used found and readily sourced materials to address concepts such as private property, exchange and black-market economies.

Of the ten artists included in We Are Story, asinnajaq and Hill are the only two with works exhibited in the McEwen Gallery (gallery 129). where you go i follow and Braided Grass both feature scenes found in nature and commentary about the relationship between humans and the environment. We recently connected with them to find out more about their approach to creation, their works in the exhibition, and the ways in which their practices reflect each other.

Foyer: Where you go i follow features an image of the shallow waters of James Bay, printed on poly-sheer fabric. Can you explain the conceptual reasoning behind this unique choice of material?

asinnajaq: While putting together their exhibition the wildflower, co-curators Becky Forsythe and Penelope Smart reached out to me about my photography. They proposed printing on fabric. At first, I rejected the idea, but after some thought, I realized the medium would add movement to an image of water. Now this medium has become part of my work, and I'm so happy that Beck and Peneople proposed it to me.

Foyer: The instructional texts or “scores” on the wall seem to suggest a oneness or attunement between humanity and the water. In your opinion, what are some of the details of this relationship and what makes it so harmonious?

asinnajaq: I have spent a lot of my life with divisions between myself and the world around me. I'm working on removing these borders, because at my core I do really believe that everything is connected. We are constantly sharing and transforming energy with the items, people, plants, animals and elements that we are connected too. The scores that accompany where you go i follow are an exercise in remembering that I'm apart of the water, and vice versa.

Foyer: What do you find moving about Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill’s work, Braided Grass? What are the main similarities you perceive between her practice and yours?

asinnajaq: Gabrielle L'Hirondelle Hill's photograph is gentle and filled with spirit. There is a gentleness in the colours of green and the drying out strands of grass that are becoming golden hay shades. This photo was taken after the movement, the moment of the artist being in relation to the grass, and shows the ephemera and traces of the relationship. At least in these two works, our intentions as artists are the same, to denote the important relationships in our lives.

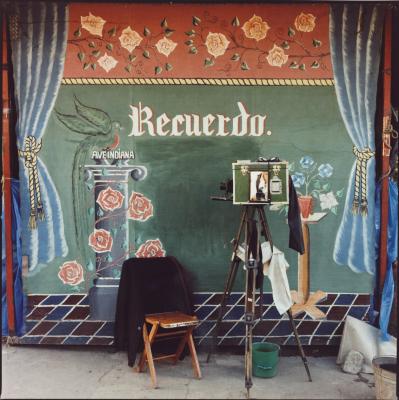

Gabrielle L'Hirondelle Hill, Braided Grass, 2013. Inkjet print. Overall: 61 x 91 cm. Purchase, Canada Now Photography Acquisition Initiative, with funds from Edward Burtynsky and Nicholas Metivier, 2021. © Gabrielle L’Hirondelle Hill. Courtesy Unit 17. 2021/72.

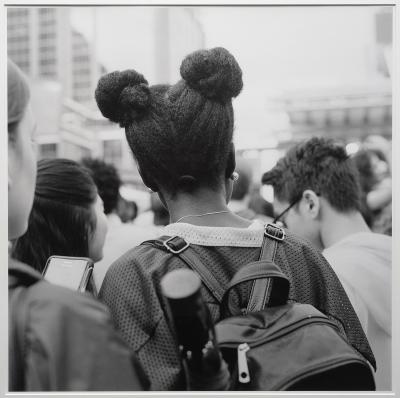

Foyer: Braided Grass depicts a powerful intervention you performed, braiding long grass beside a highway. Can you describe the meaning of this act of performance art, and what it represents to you?

Hill: I think that the meaning of that work to me has shifted as time has passed, the meaning stays open and continues to multiply, which I appreciate. I like hair: hair power, signalling through hairstyles, and also the art of the braid. I wanted to set up a braiding stand next to that hill and offer free braids — all styles. I also work with the collective BUSH gallery, and I was thinking of where the bush is in the city, the wild overgrown lots or small segments of land left unmowed. The work concerns itself with a place like that, and asserts a presence there, a being-ness.

Foyer: As noted in your bio, your projects often emerge from your understanding of capitalism as an imposed, impermanent and vulnerable system. What are some of your thoughts about the current state of global capitalism and its impact on the planet?

Hill: I am a pessimist about where the world is going, although I love people and I love the land. I read too much speculative fiction! I imagine things getting so much worse, and I plan my Go Bag.

Foyer: What do you find moving about asinnajaq’s work? What are the main similarities you perceive between her practice and yours?

Hill: I feel like asinnajaq’s works come from a place of commitment to self and community, which I love. I think we both pay attention to the small things, the materials at hand.

We Are Story: The Canada Now Photography Acquisition is on view now on Level 1 (128, The Edmond G. Odette Family Gallery, and 129 The Robert & Cheryl McEwen Gallery) of the AGO, until July 23, 2023.

![Unknown photographer, Chillin on the beach, Santa Monica [Couple on beach blanket]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-04/RSZ%20WMM.jpg?itok=nUdDiiKr)