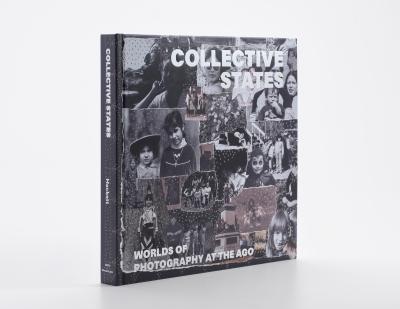

Meryl McMaster on her new work and solo exhibition

Bloodline is on view at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection through May.

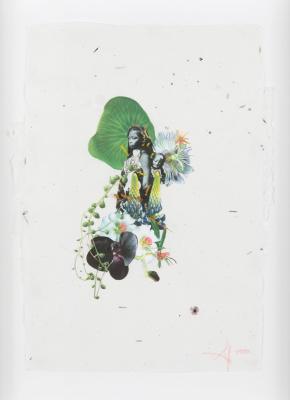

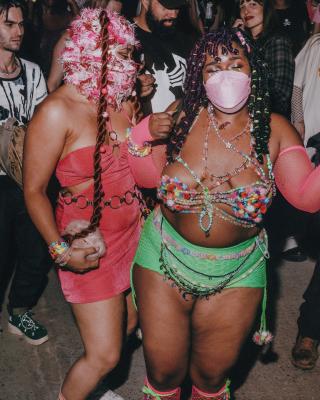

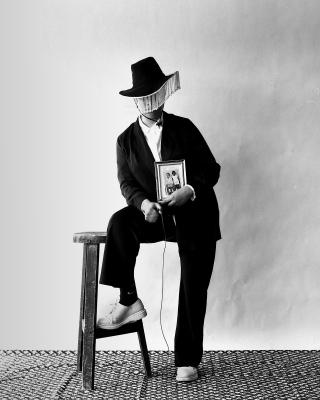

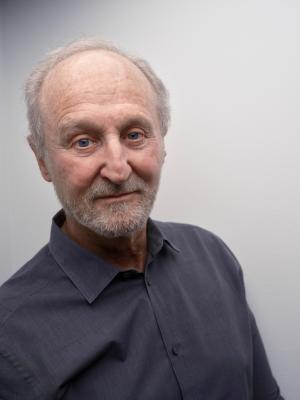

Meryl McMaster (b. 1988), Wind Play, 2012, Digital Chromogenic Print, 91.44 x 91.44 cm, Courtesy of the artist, Stephen Bulger Gallery, and Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain, © Meryl McMaster

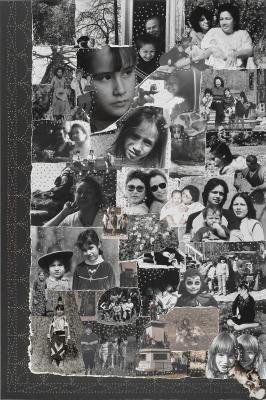

One of the most evocative contemporary artists working today, Meryl McMaster, invites visitors on a journey through her career so far with her latest solo exhibition Bloodline at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection. Highlighting works made when she was an OCADU student and continuing through to today, the exhibition presents many of the large-scale photographic works McMaster is most known for, inspired by her Plains Cree, Métis, Dutch and British ancestry. McMaster also introduces viewers to her explorations into her family histories with Stories of my Grandmothers | nôhkominak âcimowina, which foregrounds her Plains Cree female forebears from the Red Pheasant Cree Nation in Saskatchewan. Also on view for the first time are two new video-based works: niwaniskān isi kiya | I Awake To You and nipēhtēnān kiteh | We Can Hear Your Heartbeat.

Wanting to learn more, we connected with McMaster to discuss her art, its inspirations and what she hopes visitors will take away from the exhibition.

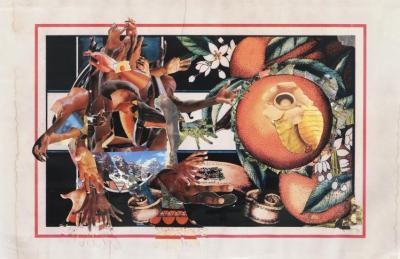

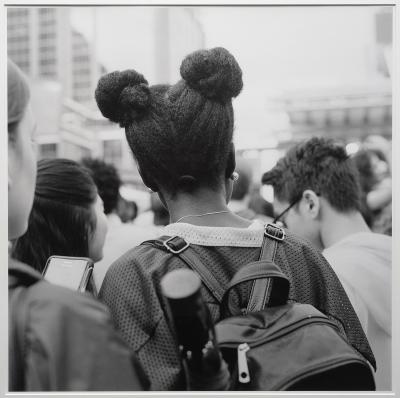

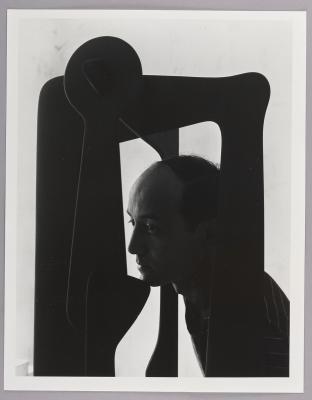

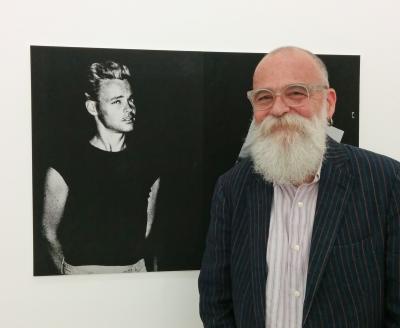

Meryl McMaster (b. 1988), The Grass Grows Deep, 2022, Giclée Print, 101.6 x 152.4 cm, Courtesy of the artist, Stephen Bulger Gallery, and Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain, © Meryl McMaster

Foyer: The exhibition comes at a meaningful juncture in your career and practice. Now that it has been up at the McMichael for a few weeks, how do you feel about it? Has the response to the exhibition (especially the newer works) illuminated anything for you?

McMaster: I feel relieved now that the show is mounted and my new work is out in the world. I’m proud of how it all turned out. It’s been three years in the making. Now I can take a deep breath.

The responses I’ve heard so far are the works have provoked questions that many ask, such as “Who am I?” and “What do I inherit from my ancestors?” Over the last number of years, I have been contemplating legacy and stories told and read about my paternal lineage. Up until now, my work has primarily dealt with the questions of being from multiple cultures, taking me on a journey in which I travelled to different parts of the country to site-specific locations.

In my newer works featured in the exhibition, I focus on my paternal grandmothers. I’ve long had many questions about the lives of my Indigenous family. I had feared many would not be answered, but this new series allowed me to focus and find some answers. I was aided by coming into possession of material my family inherited from my distant grandmothers. As well, cousins from the Red Pheasant Cree Nation were very helpful. My two surviving aunts and uncle were enormously supportive. The challenge of distance is intensified by me living so far from Saskatchewan, where I should be able to participate in daily life. Nonetheless, the comfort in knowing I’ll always have relatives on Red Pheasant is reassuring. The other reassurance is that I know a few cousins who share deeply in keeping some form of archival information and sharing it amongst family.

Foyer: Speaking of your 2015 work Time’s Gravity, you’ve explained, “I’ll always have this connection to who I am and where I’m from. That stays with me wherever I go, and informs my path in some way.” This sentiment applies to so much of your work and seems particularly relevant to Stories of my Grandmothers | nôhkominak âcimowina, for example. Do you see it that way, and how so?

McMaster: To me, there are different sides to our history and heritage. We might know very little about our family, but unless we knew the person, and inherited some personal belongings or stories, creating a larger story can be difficult. However, once you start doing this and get some success, it’s very exciting. From what I know, the weight of Indigenous history grows every day with so many books published annually. That too is exciting, but there is so much more to publish. In Time’s Gravity, I used my personal history as an indicator of how complex of an endeavour it is. The enormity and weight of personal, family, community and national history are vast. So, the question of what to keep in perpetuity is partly what this piece is about.

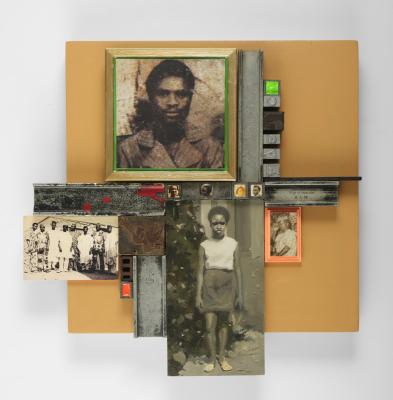

For the series, Stories of my Grandmothers | nôhkominak âcimowina, I feel I was just beginning to learn about who they were from my father, my great aunts and uncles, and cousins. Discovering that our family had my great-Grandmother Bella’s 1946 diary gave me the start to ask questions about who she was, and under what circumstances and conditions did her and the larger community of Plains Cree people live. I decided to extend this personal exploration by looking at three generations of grandmothers. Each of them had a very hard life experiencing some form of trauma. I’m grateful that my grandmothers kept some evidence of their lives, and I was lucky enough to receive their memories and knowledge through these objects and stories. While there are layers to these women that I will never know, it still gives me comfort to have access to some of their belongings, making me feel a bit more connected to them. The Plains Cree have a word, nitsikason, which means “may name is.” When I introduce myself, I would say, “nitsikason Meryl.” What the knowledge keepers told me is that the first part of the word, nitsi, means umbilical cord or belly button. This is so poetic as it really means that who I am is this connection to my grandmothers, as will be my daughters after me.

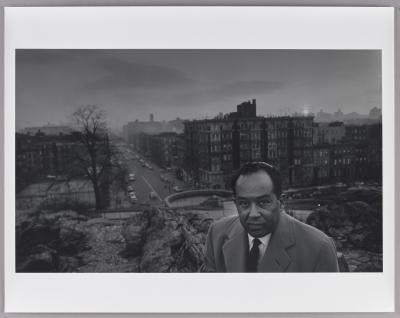

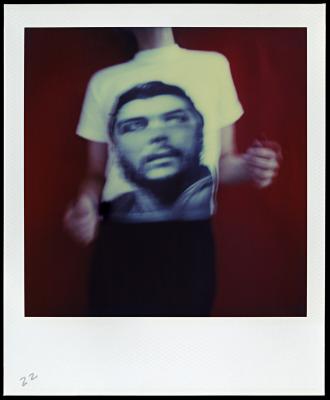

Meryl McMaster (b. 1988), Echoes Across The Field, 2022, Giclée Print, 101.6 x 152.4 cm, Courtesy of the artist, Stephen Bulger Gallery, and Pierre-François Ouellette artcontemporain, © Meryl McMaster.

Foyer: This new body of work, Stories of my Grandmothers | nôhkominak âcimowina, honours the memory of your ancestors and tells, at least, part of their stories. Take us back to when you first started looking through these belongings passed down through your family. What initial questions or feelings came to mind? Do you feel you’ve “resolved” or thoroughly explored them while creating and completing this body of work? What, if any, questions still linger?

McMaster: As a photographer looking through old family photographs, it is always exciting to imagine figures you never knew of or only heard stories about. I now have an idea of what life looked like 50-100 years ago. I remember being surprised by the pieces of writing that had belonged to my great-grandmother Bella from the 1940s and 70s. When reading her letter written in the 1970s for example, I was struck by the word she kept repeating like “wait”, “waiting” and “still waiting.” It concerned her dire situation of wanting to get assistance from the federal government to build a house of her own. Her words spoke about recognition and invisibility. With my new work, I resolved to make my grandmothers visible, since so much of their history, and Indigenous history, and most especially for Indigenous women in general, has gone unrecognized.

There were a lot of struggles my grandmothers and our people experienced under colonial rule. I think there is still much work to be done to make their stories and events more understood and appreciated. I feel my work is only a small part of helping resolve the questions I am raising.

For descendants like me, it’s important to know where I came from and to honour those who have come before to ensure their history is neither silenced nor ignored.

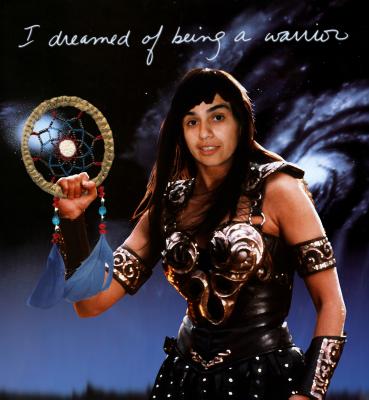

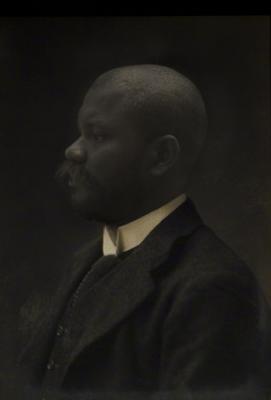

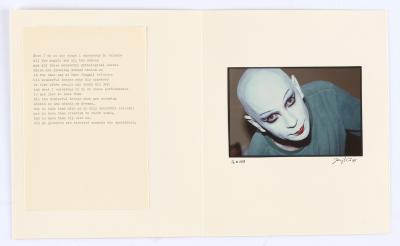

Meryl McMaster (b. 1988), Remember The Sky You Were Born Under, 2022, Giclée Print,101.6 x 152.4 cm, Courtesy of the artist, Stephen Bulger Gallery, and Pierre-FrançoisOuellette art contemporain, © Meryl McMaster

Foyer: In what seems like a natural progression in your practice, you present two video-based works in the exhibition for the first time (niwaniskān isi kiya | I Awake To You and nipēhtēnān kiteh | We Can Hear Your Heartbeat). What drew you to explore video at this point? Can you describe them to us?

McMaster: In many of my works, I feel there is a level of performance. Each photograph is like a “still” within a larger story. After coming into possession of my great-grandmother’s diary, for example, I began to consider film as a medium to bring together fragments. These fragments are not the entire story, but they are part of my journey of piecing together their stories.

I have always been curious to explore how film tells a story. I had to search for the right person to help me in the creative process. This I found in David Hartman, my co-director, who in his own right is a documentary filmmaker who tells stories of adventure and creativity.

The first film niwaniskān isi kiya | I Awake To You takes inspiration from the frequent references to trees that were told to me. I found them written in the diary and saw them in old photographs. Because Red Pheasant is located on the edge of the prairies, there are poplar trees that grow in abundance. The poplar trees supplied my family with warmth, shelter and structures for ceremonial lodges. It also offered economic livelihood and a source of traditional medicine. In the film, you will see frequent references to trees as you follow my dreaming journey. Like the trees, the lives of my ancestors were about survival, resilience and self-determination, which was shared by the three generations of grandmothers.

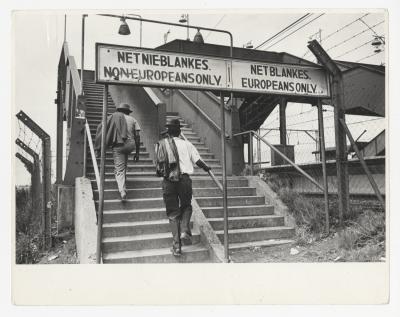

nipēhtēnān kiteh | We Can Hear Your Heartbeat was inspired by the train that no longer runs near the Rez. Objects, photographs, and stories belonging to my grandmothers speak of their connection to the train. For example, a government-issued travel card belonged to my Grandma Lena. The travel card gave “Indians” the right to ride on the train at a reduced price. In another story, Grandma Lena tells of her family travelling to Biggar (Sask.) in 1939 to see the cross-Canada tour of King George VI and Queen Elizabeth on their royal train. The trip to see this spectacle was by horse and wagon, which lasted about 12 hours. While waiting around, Grandma Lena and her brothers and sisters would put pennies on the tracks to flatten them. In another photograph I found of my great-Grandmother Bella, she was a young girl who was enrolled at the Battleford Industrial School. It shows her sitting among several male train workers along with Industrial school teachers and classmates.

All these connections to trains are filled with positive and negative stories. Trains were a powerful symbol of unity for an interconnected society across North America, but they also led to irreparable damage to the environment and greatly impacted other minority groups in the construction process and the autonomy of Indigenous nations. Trains threatened communities as settlement expanded into territories inhabited by Indigenous peoples. You will see in the film I retrace their journeys along paths to discover their memories, though the tracks have now been reclaimed by the natural world.

McMichael Canadian Art Collection

On view through May 28, Meryl McMaster: Bloodline is co-curated by McMichael Chief Curator Sarah Milroy and Tarah Hogue, Curator of Indigenous Art at Remai Modern. The exhibition is part of the 2023 Scotiabank CONTACT Photography Festival. For more details, visit https://mcmichael.com/event/meryl-mcmaster-bloodline/.

![Unknown photographer, Chillin on the beach, Santa Monica [Couple on beach blanket]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-04/RSZ%20WMM.jpg?itok=nUdDiiKr)