The Art, Life and Influence of Graciela Iturbide

In this excerpt, curator Marina Dumont-Gauthier writes about the work of the Mexican photographer

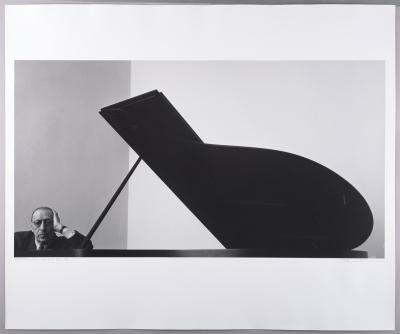

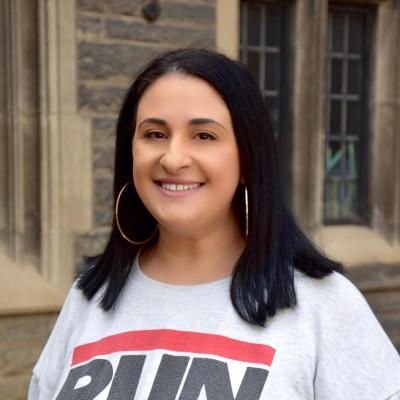

Graciela Iturbide, Serafina, Juchitán, Mexico, 1985. Gelatin silver print, 50.8 × 40.6 cm. Purchase, with funds from the Photography Curatorial Committee, 2023 (2023/73). © Graciela Iturbide.

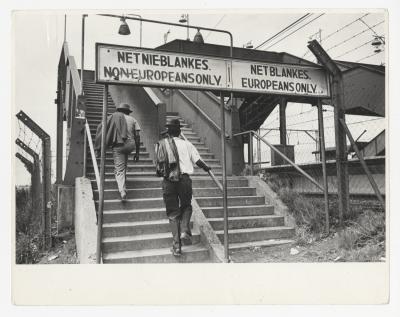

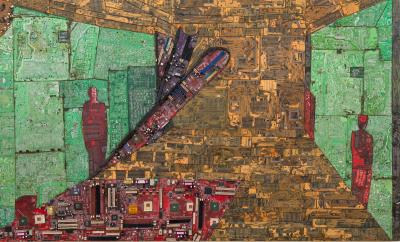

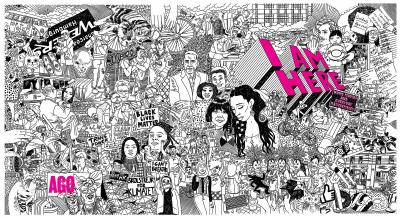

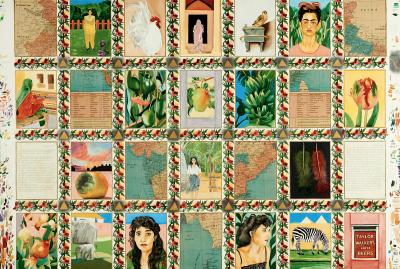

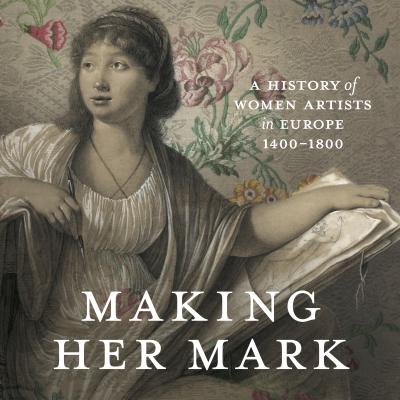

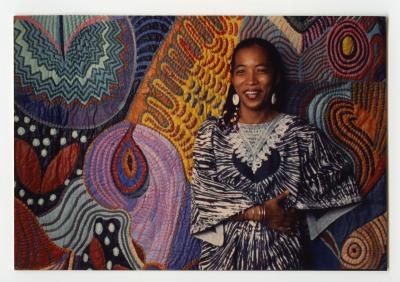

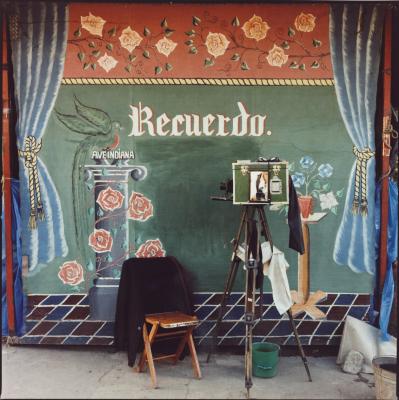

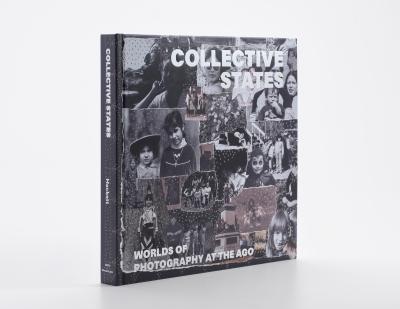

Recuerdo: Latin American Photography at the AGO has been on view since May 2025, taking visitors on a compelling visual journey through collective and personal stories that explore what it means to consider art of and from Latin America. Curated by Marina Dumont-Gauthier, Curatorial Assistant at the AGO, the exhibition brings together a range of works from the AGO Collection—many on view for the first time. Recuerdo showcases foundational Latin American image-makers, artists based in the diaspora, and Canadian photographers who have meaningfully engaged with the region.

The exhibition is accompanied by an 85-page digital catalogue, authored entirely by Dumont-Gauthier. Beautifully designed and illustrated, it features images from every section of the exhibition. Her texts explore Mexican photography from the country’s post-Revolution renaissance in the 1920s to the turn of the millennium, reportage on Cold War conflicts in South and Central America, the artistry of Graciela Iturbide, Rafael Goldchain and more.

To learn more, we turn to an excerpt from the publication in which Dumont-Gauthier reflects on the life and influence of legendary Mexican photographer Graciela Iturbide—whose works entered the AGO Collection in 2023 and are now being shown for the first time.

An Excerpt from Recuerdo’s Digital Publication

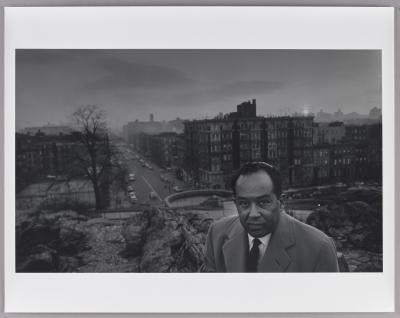

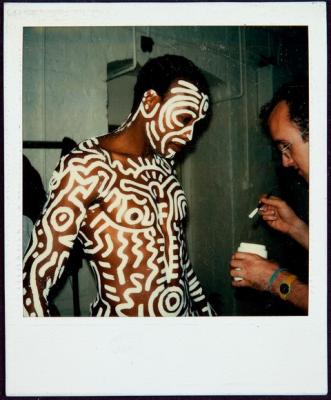

In 2023, [the AGO] acquired forty-eight photographs by Graciela Iturbide, a selection we were fortunate to make in close collaboration with the artist herself. The grouping spans the length of her prolific career and includes several important bodies of work, such as her photographs of the Seri people, an Indigenous community living in the Sonora desert; the Zapotecs living in Juchitán de Zaragoza, Oaxaca; a selection of self-portraits; and works from her time in India. This momentous acquisition represents our largest holding of works by a single Latin American maker and is a deeply significant addition to our trove of Mexican photography. Iturbide’s intuitive eye, coupled with a profound sense of connection and empathy for her subjects, has yield an unparalleled oeuvre, one that is defined by poetic expressions that explore the intersections and contradictions between tradition and modernity, identity and gender, life and death, and the secular and the sacred. Kristen Gresh, who curated the 2019 exhibition Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico, describes the photographer’s account of Mexico as transcending the boundaries of documentary, anthropological, and ethnographic photography. She likens Iturbide’s work to that of Robert Frank (1924–2019) and Diane Arbus (1923–1971) in the United States, particularly for the ways in which they were able to present society both within and outside the mainstream.2

![Graciela Iturbide, Día de muertos [Day of the Dead], Juchitán, Mexico](/sites/default/files/styles/max_1300x1300/public/2025-07/GI%20image%202%20pt%202%20cropped.jpg?itok=xfCNhhPb)

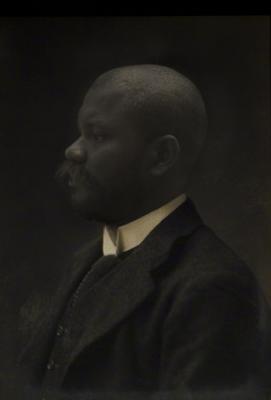

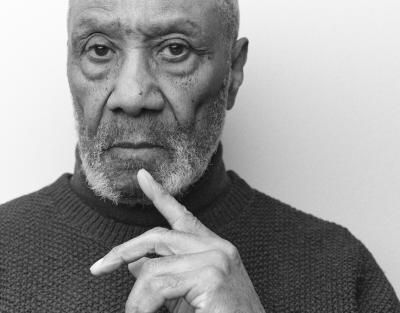

Graciela Iturbide, Día de muertos [Day of the Dead], Juchitán, Mexico, 1986. Gelatin silver print, 25.4 × 20.3 cm. Purchase, with funds from the Photography Curatorial Committee, 2023 (2023/62). © Graciela Iturbide.

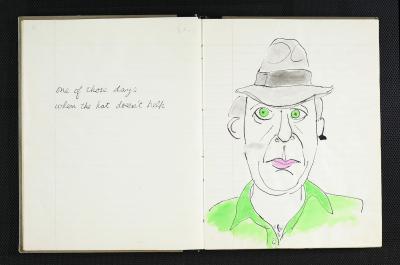

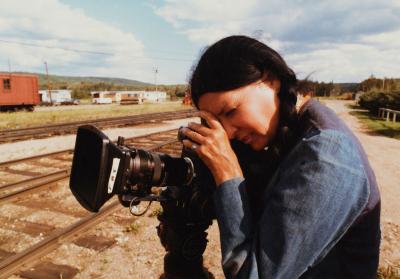

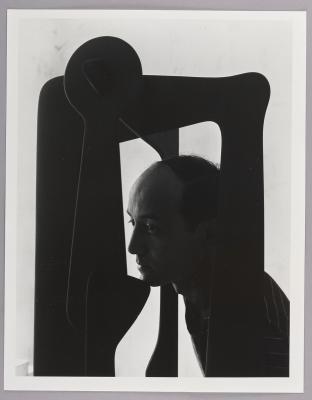

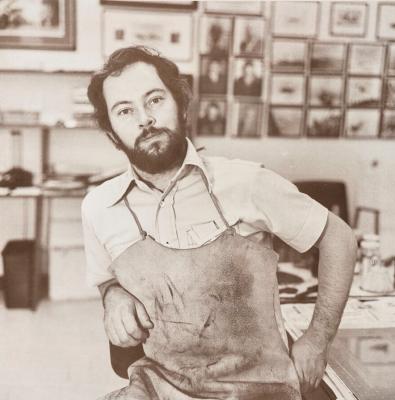

Iturbide’s career, now spanning more than five decades, began in 1969 when she enrolled at the Centro de Estudios Cinematográficos (Center for Cinematic Studies) at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). “I would have liked to have taken philosophy and literature courses and become a writer,” she says, “but I was already married and had children. I heard about the film school and I was so eager to do something with my life that I enrolled.”3 She soon found herself drawn to the art of still photography, a shift from film that was further solidified when she met Manuel Álvarez Bravo who, then nearing age seventy, was teaching photography at the university. Iturbide became his apprentice, or achichincle, accompanying him on various photographic journeys across Mexico. Along with the apprenticeship, which lasted less than two years, the friendship that followed had a profound impact on Iturbide’s life. 4

“My first photographs were in Mexico because it was a way to get to know my culture, which I didn’t have access to as a child because I lived in another world. That’s why I tell you that I owe everything to Álvarez Bravo. He opened my eyes to my country’s culture … “[m]ore than being my teacher of photography, Don Manuel taught me about life.”4

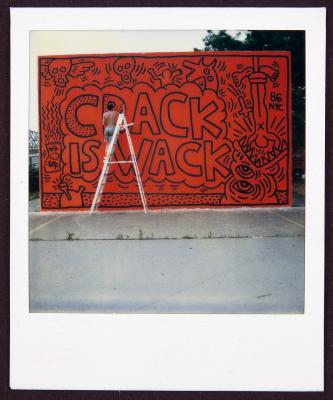

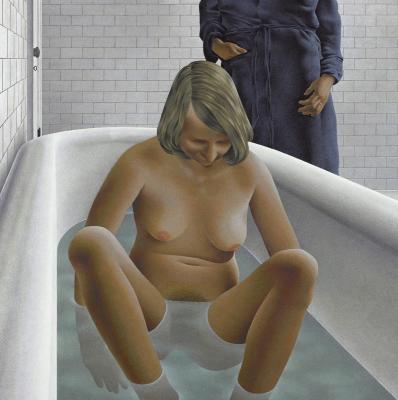

Graciela Iturbide, Doña Guadalupe, Juchitán, Mexico, 1986. Gelatin silver print, 25.4 × 20.3 cm. Purchase, with funds from the Photography Curatorial Committee, 2023 (2023/61). © Graciela Iturbide.

By the mid-1970s, Iturbide had traveled extensively across Latin America, gradually developing a photographic style of her own. She recalls how her mentor, who seldom commented on her work, told her after seeing a photograph she had taken in Panama of children with their fists raised in the air: “Graciela, everything in life is political. Don’t deliberately take anything literally.”5 This advice had a significant influence on her work, which became increasingly imbued with intrigue and ambiguity, while also becoming deeply rooted in symbolism.

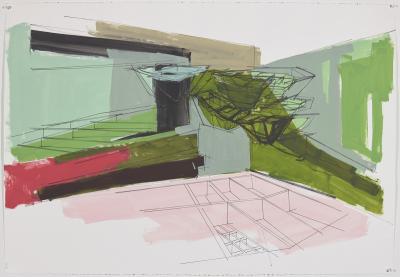

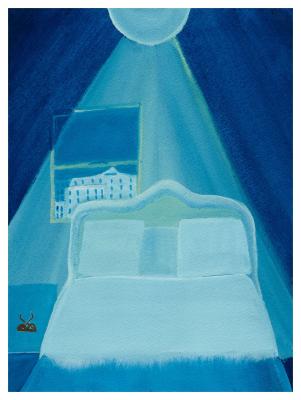

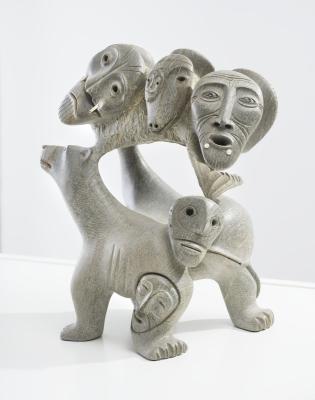

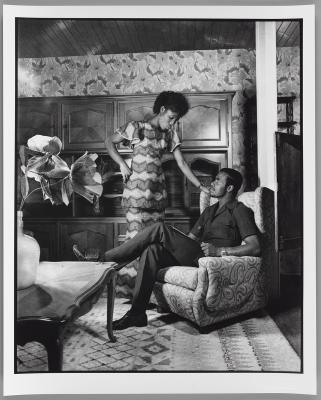

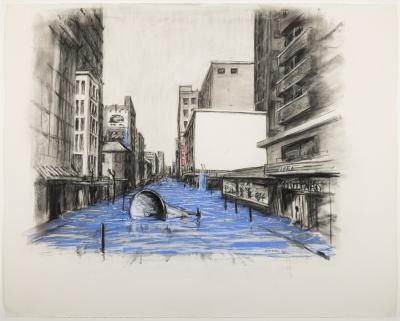

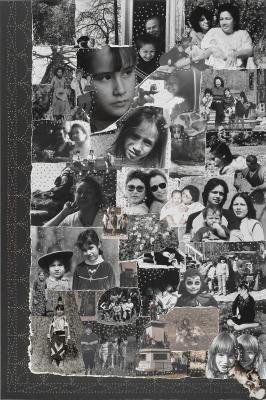

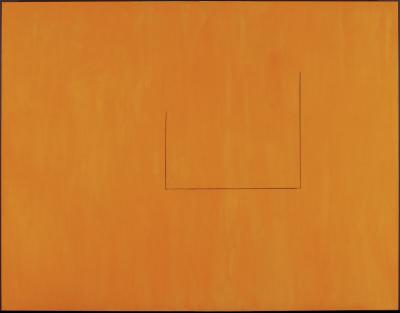

In 1979, Iturbide was invited by the Mexican artist Francisco Toledo (1940–2019) to photograph the Juchitán people, who are part of the Zapotec culture native to Oaxaca in southeastern Mexico. “My work in Juchitán lasted six years, with several interruptions,” she says, “[a]t the beginning, I didn’t think I would make a book of it because the project was not intended as a photographic study, but I was fascinated by the place.”6 The book in question, Juchitán de Las Mujeres (1989), offers a poignant account of Iturbide’s experience living with the women of the region. Forming a matriarchal society, the Juchitecas manage all facets of daily life— from the economy to social rituals—and have played a vital role in the evolution of Mexico’s visual identity, appearing in the works of key makers such as Tina Modotti and Frida Kahlo (1907–1954).

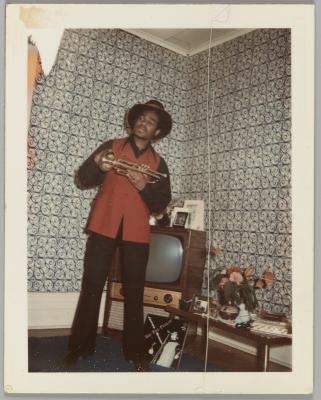

![Graciela Iturbide, Nuestra Señora de las Iguanas [Our Lady of the Iguanas], Juchitán, Mexico](/sites/default/files/styles/max_1300x1300/public/2025-07/GI%20contact%20sheet%20cropped.jpg?itok=SsRC6wCw)

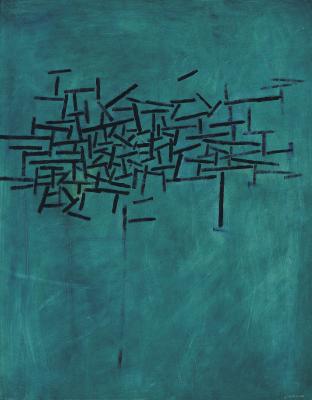

Graciela Iturbide, Nuestra Señora de las Iguanas [Our Lady of the Iguanas], Juchitán, Mexico [contact sheet], 1979. Gelatin silver print, 27.9 × 35.6 cm. Purchase, with funds from the Photography Curatorial Committee, 2023 (2023/75). © Graciela Iturbide.

The women quickly took Iturbide under their wing, granting her access to private and intimate aspects of their lives. She photographed people of all ages while there, capturing them in traditional garments, nude, or in modern attire, and across a variety of settings, including inside their homes, at the market, in cemeteries, and participating in political demonstrations. The photographs convey a closeness and a playfulness that manifest the strong bonds she formed with the community. Reflecting on that closeness, Iturbide says:

It’s how I’ve always worked, with a handheld camera but always with people’s complicity … I might have missed a few good photos, but it was so essential to really be with the woman who was next to me … I don’t remember the images I may have sacrificed, but I remember the situations I missed out on perfectly.

This excerpt is written by Marina Dumont-Gauthier, Curatorial Assistant at the AGO. Click here to read the full essay and the rest of the digital catalogue. Recuerdo: Latin American Photography at the AGO is on view now until October 19, 2025 on Level 1 of the AGO.

1. Graciela Iturbide, “Interpreting Reality,” World Literature Today Vol. 87, no. 2 (2013): 119.

2. Kristen Gresh, Graciela Iturbide’s Mexico (Boston: MFA Publications, 2019), 11, 15. I am deeply indebted to Gresh’s insightful scholarship on Iturbide, an artist with whom she has worked closely for many years.

3. Iturbide, quoted in Graciela Iturbide: Heliotropo 37 (Paris: Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 2022), 8. Iturbide divorced her husband, the architect Manuel Rocha Díaz, shortly after joining the program: “My divorce caused a scandal. But when I got divorced, despite the fact that I had a good relationship with the father of my children, I felt liberated. I was able to do my jobs, both in photography and in film … I felt very happy to be myself, to be free, and to be alone. Photography was my passport.” Iturbide, quoted in “In Conversation with Graciela Iturbide,” Prix Pictet: In Focus (2002). Retrieved from prix.pictet.com/ in-focus/in-conversation-with-graciela-iturbide.

4. Iturbide, quoted in “Graciela Iturbide Dreams & Visions,” Aperture, no. 236 (Fall 2019): 30.

5. Álvarez Bravo as remembered by Iturbide, quoted in Heliotropo 37, 12.

6. Iturbide, quoted in Heliotropo 37, 16.