Pacita’s textiles with Clarissa M. Esguerra

LACMA’s Curator of Textiles and Costumes reflects on how Pacita Abad transformed textiles in her art

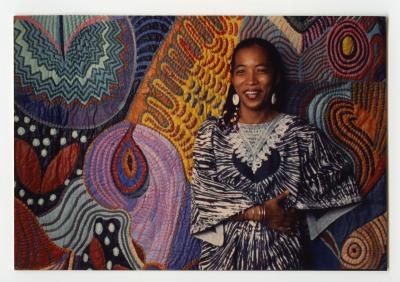

Pacita Abad with Bacongo I (1983) in her Washington, DC, studio, 1986. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate.

Pacita Abad (1946 – 2004) was an artist and world traveller who meticulously collected fabrics and materials from every country she visited. Across 63 countries and 32 years, Abad amassed a large collection of cultural textiles, from scraps of traditional fabrics to outfits that constituted her daily and formal attire.

Her collection of textiles wasn’t meant to sit untouched. She used them in her art, creating large, vibrant collages called trapuntos, a hybrid art form she created. Bringing together textiles from various cultures, these quilted canvases critiqued the Western colonization and treatment of the Global South.

On view now at the AGO, the exhibition Pacita Abad features over 100 works showcasing her range of mediums, including the various ways she incorporated textiles into her work. The exhibition includes a textile map that traces Abad’s international travels and highlights several of the traditional fabrics Abad incorporated into works on view.

For Clarissa M. Esguerra, Curator of Textiles and Costume at Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Abad’s incorporation of global textiles speaks to the artist’s deep understanding of cloth as a carrier of culture and history.

It was during her BFA in fashion design that Esguerra started to notice the political and historical events she was learning about in her gender studies minor were reflected in fashion and dress. Intrigued by fashion history, she went on to get her M.S. in Historic and Cultural Aspects of Dress and Textiles from the University of Georgia.

Esguerra has co-curated the exhibitions Lee Alexander McQueen: Mind, Mythos, Muse and Reigning Men: Fashion in Menswear, 1715-2015. Marking a shift in her practice, Esguerra stepped outside of Western textiles with her 2019 exhibition Power of Pattern: Central Asian Ikats from the David and Elizabeth Reisbord Collection.

Currently, Esguerra is working on an exhibition dedicated to the textiles and fashions of the Philippines. She also wrote an essay on Abad’s textile work for the Walker Art Center during their presentation of the Pacita Abad exhibition.

Foyer caught up with Esguerra to talk more about the impact of Abad’s textile work, as well as Esguerra’s reflections on the exhibition as a textile expert and a Filipino American.

Clarissa M. Esguerra, LACMA Curator of Textiles and Costumes. Photo by Justin Loy.

Foyer: As a curator specializing in European menswear, and as a Filipino American, how do these aspects of your identity influence how you perceive Abad’s work?

Esguerra: I've always loved fashion, and the fashion that was easily accessible to me growing up in Georgia was Antebellum fashion – historic dress during the Civil War era and there after. As a result, the category of dress that I first excelled at was Victorian American dress. As I was getting into gender studies, I realized that in terms of dress history and literature about the fashions of that time, there was very little written about menswear, only about women's wear. When I went into my graduate degree at the University of Georgia, I explored the rigidity of menswear; where the suit came from; and why is it that in other cultures in the world, men wear unbifurcated dress but in the United States and the West, it's always about trousers on men.

Where I grew up, there was very little representation of Asians in general, let alone Filipinos. I often was faced with fellow classmates who would question that I was Asian because I'm dark-skinned. In their minds, they were thinking of East Asia, not understanding Asia is the biggest continent in the world and that it's incredibly diverse. They would say things like, ‘you look South American,’ and [at the time] I didn’t know there's actually a deep history between the Americas and the Philippines, with the Manila Galleon Trade and then later the American colonization. I didn't have a lot of representation, and I just kind of gravitated to what was available. It really wasn't until now in my mid-career that I'm deeply getting into Philippine dress and textiles. It's very much a part of this kind of existential reawakening that's happened all throughout my life, but now I can finally do something actionable about it to really understand where I come from.

Installation view of the exhibition Pacita Abad: A Million Things to Say at the Museum of Contemporary Art and Design, Manila, De La Salle-College of Saint Benilde, 2018. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate and MCAD Manila. Photo: At Maculangan/Pioneer Studios.

Abad joined a wave of feminist artists from the 1960s to 1970s who reclaimed textiles as an art form, rather than women’s domestic labour. What kind of intervention did Abad, her trapuntos, and her greater textile practice make in contemporary art?

What I love about Abad’s work is that her use of textiles references a very long history of textiles as art throughout the world, including the Western world. Textiles were considered one of the most ancient luxuries aesthetically and technically, and it was easy to transport. She's tapping into this history when textile making wasn't considered just a domestic task.

Her work reminds me of people who engaged with the Silk Road, how they went from one place to another collecting pieces of fabric specific to a place and a culture. Textiles embody culture. It illustrates the land, what resources are available there, the techniques and the aesthetics, and also any interaction with other cultures that have come through and have been absorbed. Her practice of travelling around the world and collecting textiles references a very old practice of collecting luxury textiles as bits of a culture [traders] were able to interact with.

This feeds into my next question: Abad amassed an impressive collection of textiles and materials from her travels, which she used to create vibrant collages. What can Abad’s work tell us about global textile cultures and how they interact?

The way that she puts textiles into her paintings, and then adds her own personality to it by collaging it, quilting it, painting it and then adding more and more, she's referencing history and a specific culture but also bringing in her own meanings and making it something new. [Her work is] reverent of both the past and the places that she's been to, but also reflecting upon big themes that we still are grappling with today.

There are cultures in the world that just cloak their entire living spaces with textiles. They’re layered in these tall bundles on the floor, on the ceiling, around the walls. If you think about the tents of nomadic people of Central Asia, through the Ottoman Empire and India, textiles were a way to have a visual garden in your personal space, and you could roll it up and take it with you wherever you go. Textiles were appreciated for their functionality to shelter, to provide comfort, to clothe your body, to provide something to sleep on like a cushion. But it's also beautiful. Textiles are useful, but why not let this useful thing also be beautiful too, right?

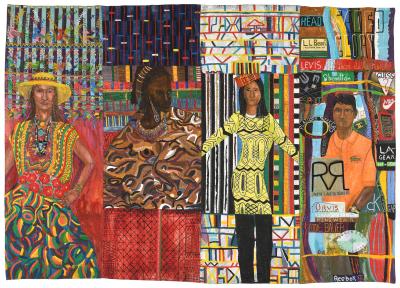

Pacita Abad. 100 Years of Freedom: From Batanes to Jolo, 1998. oil, acrylic, Philippine cloth (abaca, pineapple, jusi, and banana fibres; Baguio ikat; Batanes cotton crochet; Ilocano cotton; Chinese silk and bead; Spanish silk; Ilongo cloth; Mindanao beads; Zamboanga and Yakan handwoven cloth and sequins) on stitched, and dyed cotton fabric. Courtesy of Pacita Abad Art Estate. Photo: Chunkyo In.

On view in Pacita Abad, 100 Years of Freedom: From Batanes to Jolo is a deeply personal work consisting of textile materials Abad sourced as she travelled across the Philippines in the 1970s. This includes many family heirlooms. Can you speak to why this work is an important representation of Filipino textile culture, and how this relates to the title Abad chose for the work?

This work was celebrating the centennial of the Philippines declaring independence from Spain. Unfortunately, they later became colonized by the US.

In this work, Abad was looking at this archipelago of diverse cultures and people who spoke many different languages as a whole. The thing that really connected all these communities, because the country itself was created politically, is their shared seas, which acted more like bridges than barriers, and the ways they were all resisting colonization. If you think of groups in certain parts of the Cordilleras (the mountains of Luzon, in northern Philippines) and Mindanao (in southern Philippines), they were able to resist Spanish colonization. It's quite amazing. Many regions were able to keep their indigenous identities, and it often lived through the textiles. Abad pays tribute to that in 100 Years of Freedom, where she's visually collecting pieces of all these cultures into one monumental work that celebrates this archipelago.

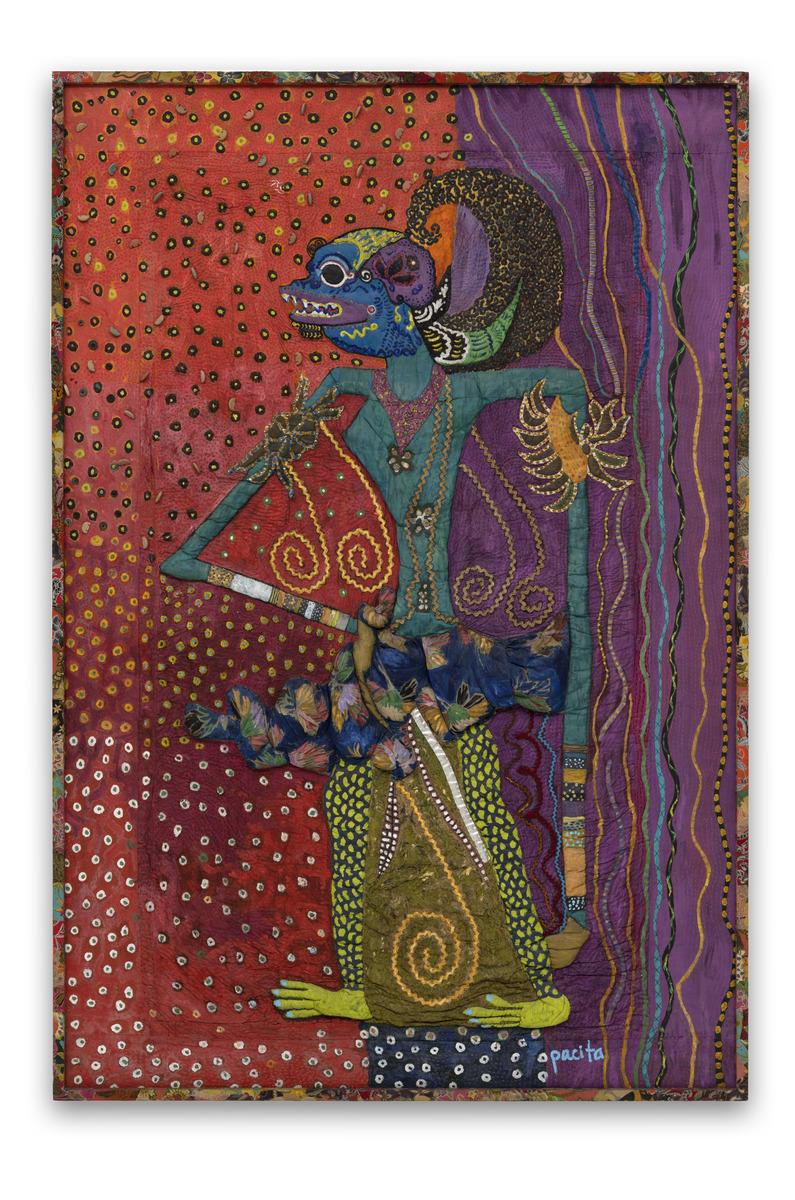

Pacita Abad. Subali, 1983/1990. Acrylic, oil, gold cotton, batik, cloth, sequins, rickrack ribbons on stitched and padded canvas. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate. Photo: Rik Sferra for Walker Art Center.

You are currently working on an exhibition dedicated to the fashion and textiles of the Philippines. What kinds of ideas and themes are you hoping to explore with this exhibition?

I'm in the very early stages of it, but I am looking at centering Philippine dress and textiles globally. I’m hoping to show them with works from all over the world to illustrate the hybridity of the Philippines. It's kind of like a microcosm of the world if you look at its textiles. You can see aspects of the Ottoman Empire. You can see aspects of India. You can see aspects of the Americas, Spain, and Taiwan. There are parts of the Philippines that almost feel exactly like Borneo, Malaysia, and Indonesia, and it's because of its long history of being a huge point of commerce.

This marks a shift in your practice, has that been challenging? Affirming?

It's been challenging because I'm frustrated that I didn't learn this when I was younger. It's challenging in that I'm realizing that my understanding of the Philippines is coloured by the history of Western art. I have to be mindful to go into everything with deep curiosity and to understand my own biases. We try to do that with everything we don't understand, but now I have to do it with my own ethnicity It's also been really invigorating to be able to imagine people making these textiles. To actually imagine somebody who looks like me has been really powerful.

Pacita Abad. Shallow Gardens of Apo Reef, 1986. Oil, acrylic, mirrors, plastic buttons, cotton yarn, rhinestones on stitched and padded canvas. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate and MCAD Manila. Photo: At Maculangan/Pioneer Studios.

What aspects of Abad’s works resonate with you as a curator of textiles and costumes, and as a Filipino American?

Her exuberance. Her use of colour and pattern. Her deep understanding of textiles as an ancient art form is so clear when I see her work. It's incredibly powerful to see this art from a fellow Filipino American. To see someone of your heritage reflected on the walls, on top of the fact that her medium blends techniques and materials that are outside of the Western art historical canon is powerful.

View textiles from around the world in the exuberant work of the late Filipina artist in Pacita Abad, now on view at the AGO on Level 2 in the Sam & Ayala Zacks Pavilions (galleries 244 and 245). Organized by the Walker Art Center in collaboration with Abad’s estate, the exhibition is curated by Victoria Sung, Phyllis C. Wattis Senior Curator at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), and former associate curator, Visual Arts, Walker Art Center; with Matthew Villar Miranda, curatorial associate at BAMPFA, and former curatorial fellow, Visual Arts, Walker Art Center. The AGO presentation is organized by Renée van der Avoird, Associate Curator, Canadian Art.