The colourful life of Pacita Abad

Five facts about the late Philippine-born artist that illustrate the bold life and practice she led

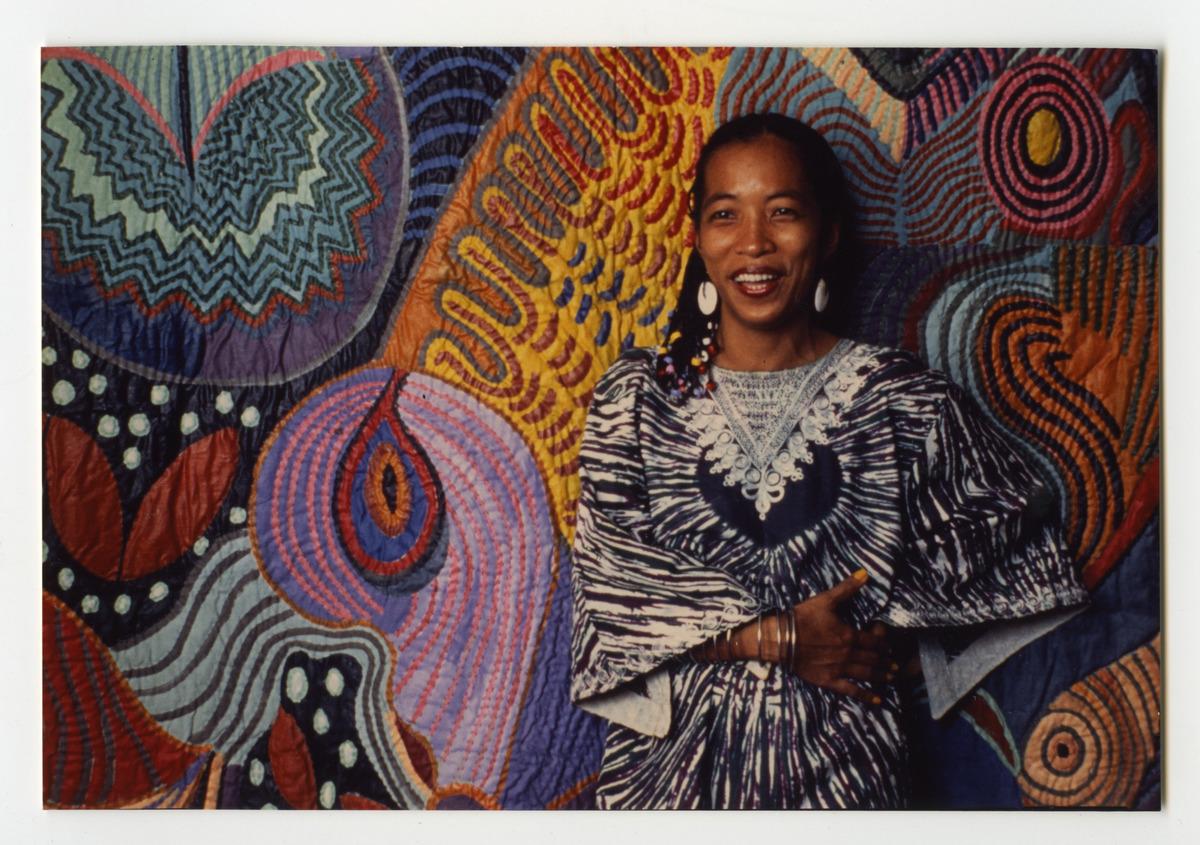

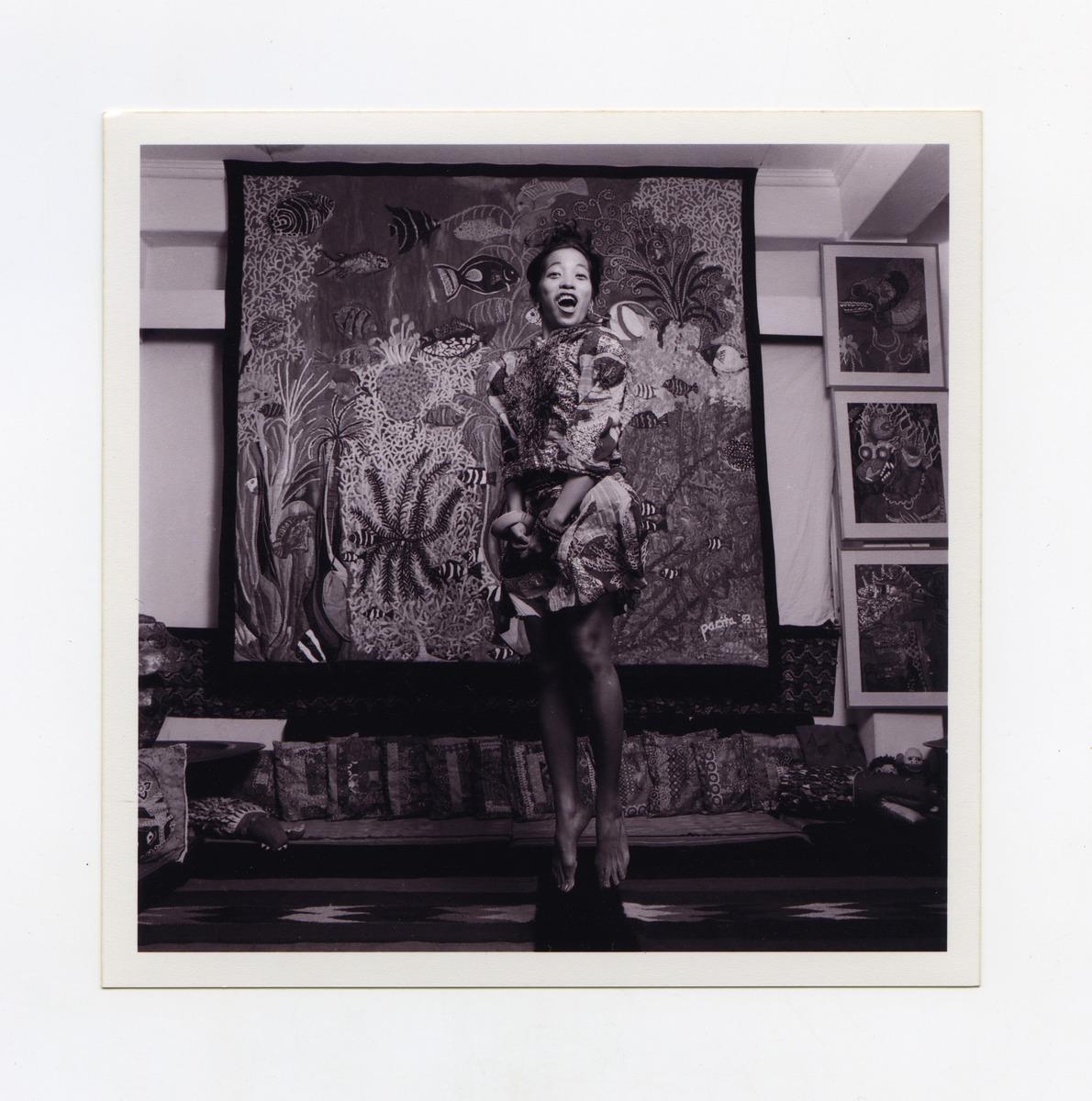

Pacita Abad with her trapunto painting Ati-Atihan (1983) wearing garments and jewelry collected on her travels. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate.

Political activist, world traveller, and scuba diver — the life of late Philippine-born artist Pacita Abad (1946 - 2004) was as colourful as the art she created.

The fifth child of 13, Abad was born in 1946 in Batanes, the smallest and northernmost Philippine province. Her life and art, however, were anything but small. Her works were bold and unapologetic, challenging Western art ideals and exposing colonial subjugation across the Global South.

Now on view at the AGO, Pacita Abad marks the artist’s first retrospective and the Canadian debut of her work. First presented at The Walker Art Center, the exhibition features over 100 works showcasing Abad’s range in mediums, studio ephemera, and an archive of materials she used in her practice.

As you take in Abad’s grandeur and exuberant works alongside her extensive personal lore, you may be surprised to learn that her work was largely under-appreciated during her time and even after her passing. As we welcome Abad’s work to Canada for the first time at the AGO, here are five of Abad’s most interesting accomplishments.

1. She challenged and met with Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

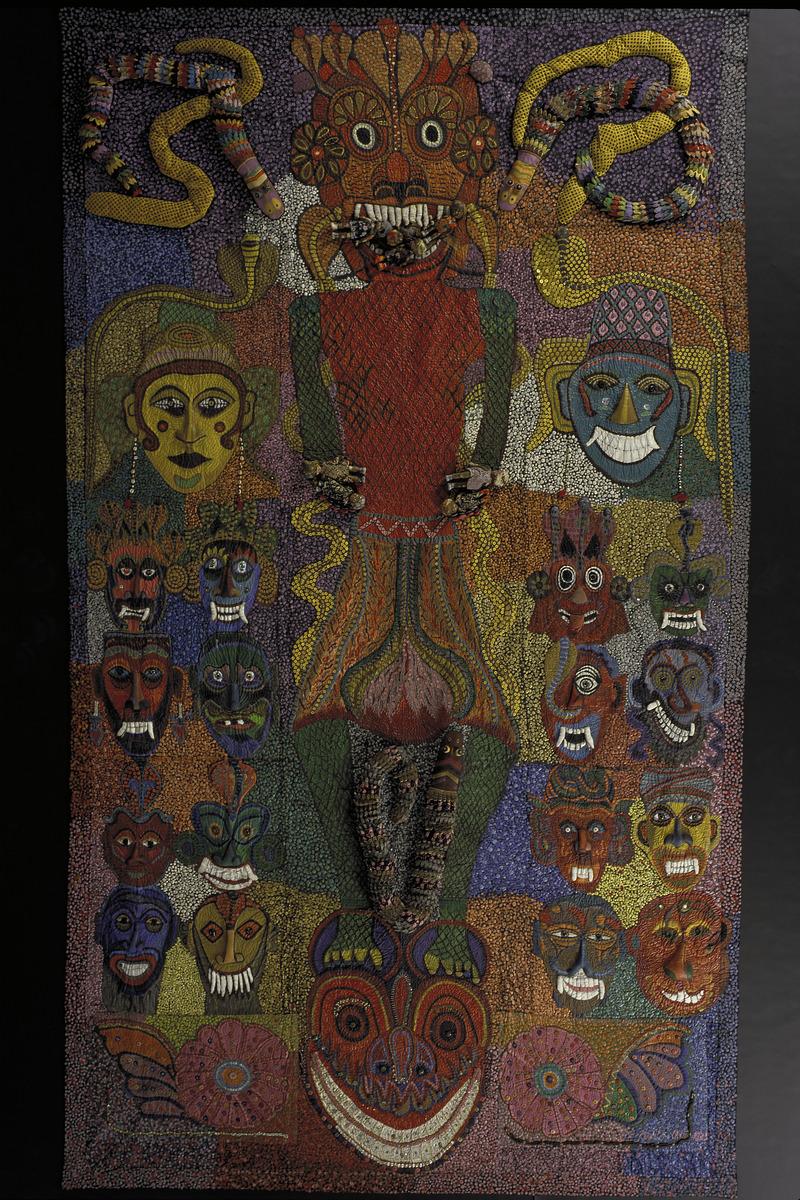

Pacita Abad. Marcos and his Cronies, 1985-1995. Mixed-media painting. Collection Singapore Art Museum. Courtesy Pacita Abad Estate and Singapore Art Museum.

The copyright of this artwork belongs to the artist or their authorized representatives and may not be reproduced for any purpose whatsoever without the prior written permission of the Singapore Art Museum/National Heritage Board and/or copyright owners.

Much of Abad’s oeuvre was highly political, and her critical lens came from growing up in one of the Philippines’ most influential political families.

Abad’s father, Jorge Abad, was elected to the Philippine House of Representatives and served in this position for 13 years before being appointed the Secretary of Public Works & Highways. Abad’s mother, Aurora Abad, campaigned and was elected to her husband’s previous seat.

Naturally, Abad went on to study political science at the University of the Philippines (UP) in Quezon City before starting her graduate law studies in 1969. That same year, Philippine Dictator Ferdinand Marcos was running for his second term. This was historically one of the most violent and corrupt elections in Philippine history. At the hands of the same fraudulent tactics that got Marcos re-elected, Abad’s father ended up losing his congressional re-election campaign. Angered by fraudulent elections across the country, Abad organized a student protest in Manila. This led to her and other student organizers meeting with Marcos, surrounded by the dictator’s generals. However, this meeting did not intimidate nor sway Abad, as she continued organizing student demonstrations that gained national media attention.

Eventually, her protests helped lead the Philippines Commission on Elections to overturn her father’s election results in his favour. That night, the Abad family home was targeted with gunfire, but thankfully no one was hurt. Abad continued to protest political corruption under the Marcos regime until increased threats against her life forced her to leave the Philippines.

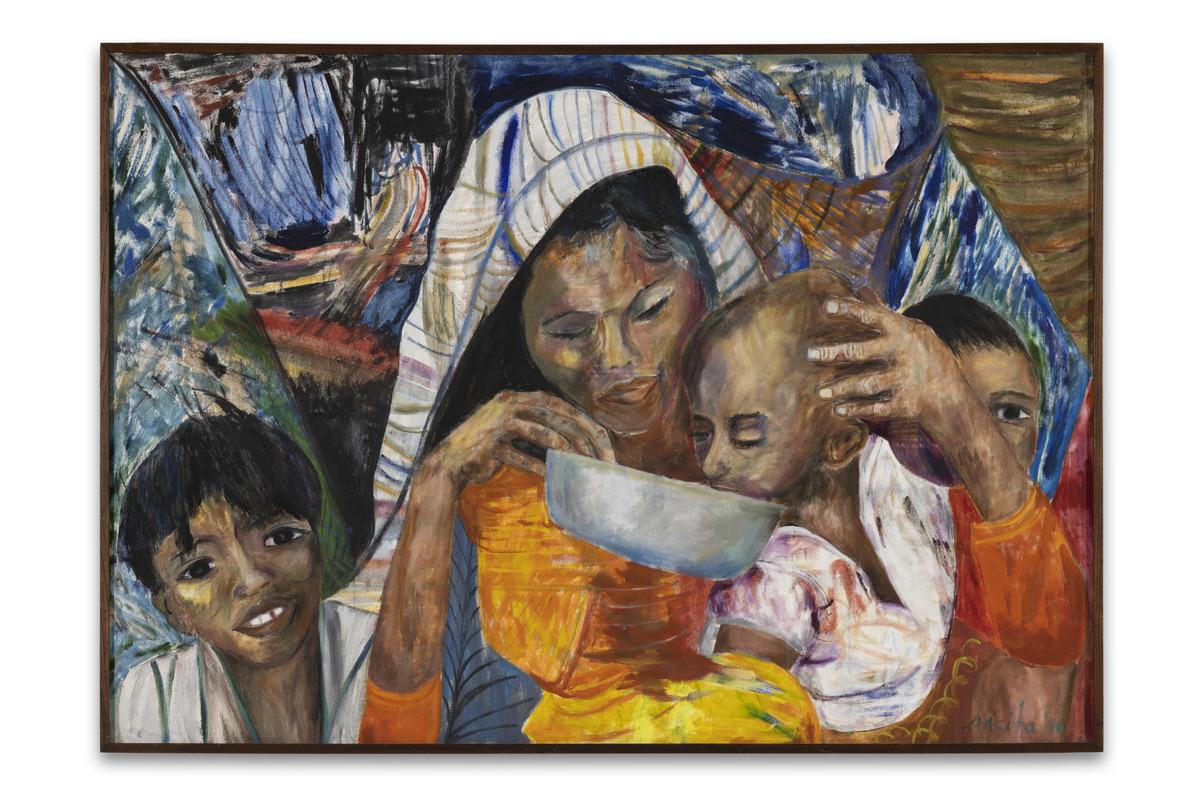

Pacita Abad. Water of Life, 1980. Oil on canvas. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate. Photo: Rik Sferra for Walker Art Center.

Abad’s political activism remained a key aspect of her work as she critiqued Western treatment of migrants and immigrants from the Global South, the intricate global network of colonization, and Eurocentrism. Though she left the Philippines, Marcos was never far from her mind. One of her largest works, Marcos and His Cronies (1985- 1995) (above) depicts the dictator as a demon, eating Filipino children as he stands on the head of his wife Imelda Marcos. The dictator is surrounded by corrupt cabinet members, military generals, and businessmen, also depicted as demons. This work was inspired by Abad’s time in Sri Lanka when she came across Sinhalese exorcism masks. She felt like the Philippines deserved an “exorcism” from Marcos and his regime.

2. She travelled to over 60 countries in 32 years.

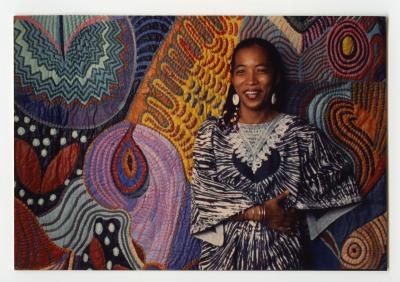

Pacita Abad with Puerto Galera I (1983) in her Manila home, 1985. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate. Photo: Wig Tysmans.

Abad was a global citizen, or as she called herself, “a woman of the world.” While she travelled to an impressive 63 countries during her lifetime, what was truly remarkable about her global adventures was how she found inspiration from the cultures she came across, such as in Macros and His Cronies.

After she left the Philippines in 1970, Abad visited her aunt in San Francisco on the way to Madrid, where she planned to finish her law degree. She decided to stay in the United States and pursue a master's degree in history. During her studies, she met fellow graduate student Jack Garrity, who became her travel partner and later, her husband.

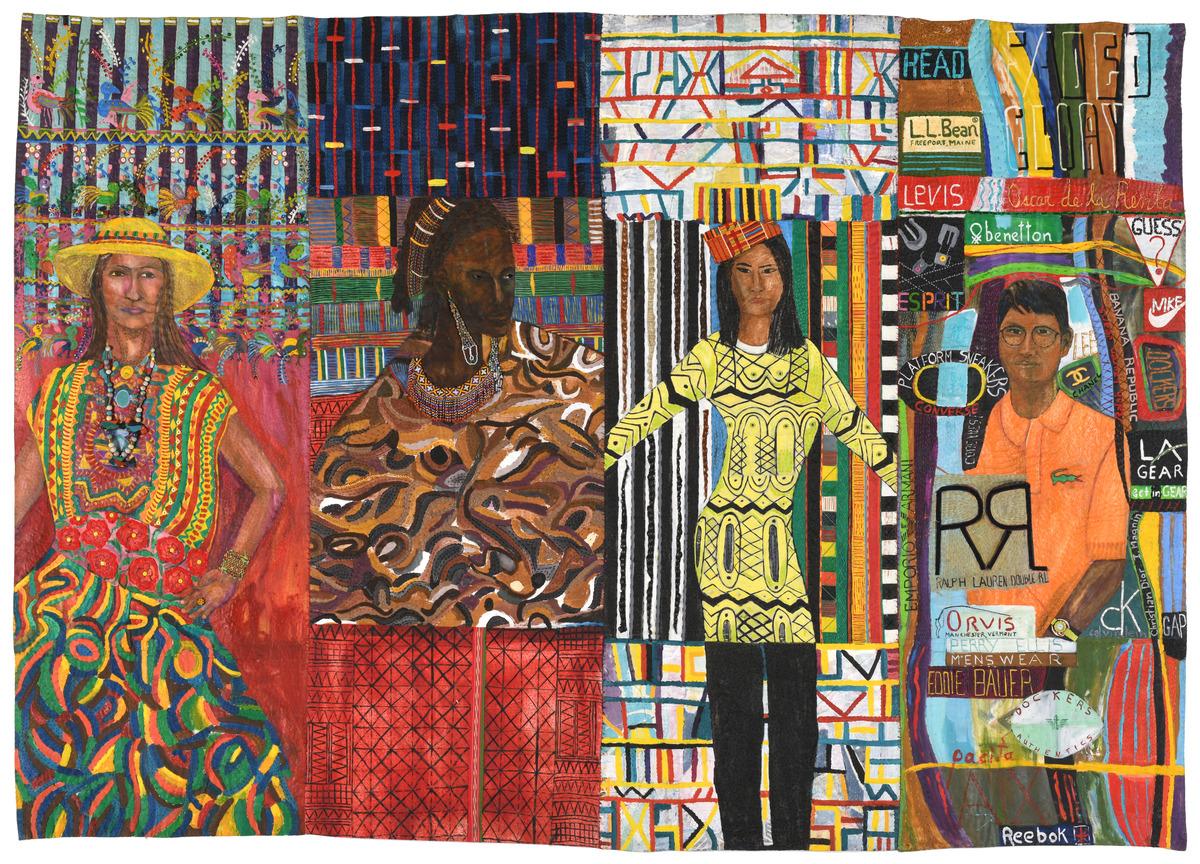

The two decided to take a trip hitchhiking overland from Turkey to the Philippines. On this trip, Abad began collecting materials such as textiles, jewellery, and beads from the countries she visited. Over her travels, she amassed quite a collection and used many of these materials in her work. Her work meaningfully incorporated cultural iconography, material, and colour schemes, rejecting Eurocentric ideals of art for Indigenous motifs and patterns resulting in critics often calling her work “decorative,” “child-like,” “ethnic,” and “naive”.

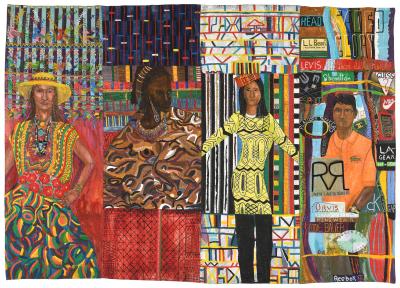

Pacita Abad. Cross-cultural Dressing (Julia, Amina, Maya and Sammy), 1993. Oil, cloth, plastic buttons on stitched and padded canvas. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate and Spike Island, Bristol. Photo: Max McClure.

Through her time in the United States and her travels, Abad became interested in representing the interlinked struggles of refugees, migrants, and inhabitants of the Global South. She built connections with the artisans of the communities she visited, exchanging ideas and working collaboratively. While she was a global citizen, her Filipina identity, and the history of Spanish, Japanese, and American colonization in the Philippines allowed her to connect deeply with communities living through similar circumstances. Abad’s work materialized connections between the displaced, the colonized, and diasporic communities worldwide, dreaming of replacing colonial structures with a non-hierarchical, multi-dimensional idea of unity.

As Victoria Sung, former associate curator of Visual Arts at the Walker Art Center and co-curator of Pacita Abad points out in the exhibition catalogue Pacita Abad, the following photograph probably best documents Abad’s personification as a “woman of the world.”

Pacita Abad with Bacongo I (1983) in her Washington, DC, studio, 1986. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate.

Here, Abad poses next to her work Bacongo I (1983), which comes from her series of eight large-scale quilted masks inspired by her time in what is now known as the Republic of Congo and the Democratic Republic of Congo. The masks represent bifwebe masks worn by Songye and Luba dancers to enhance their movements. Posed beside Bacongo I, Abad wears a dress from Palestine, ivory bracelets from Sudan, a necklace from Afghanistan, and tin earrings from Kenya — all materials picked up from her travels.

3. She developed her own art form.

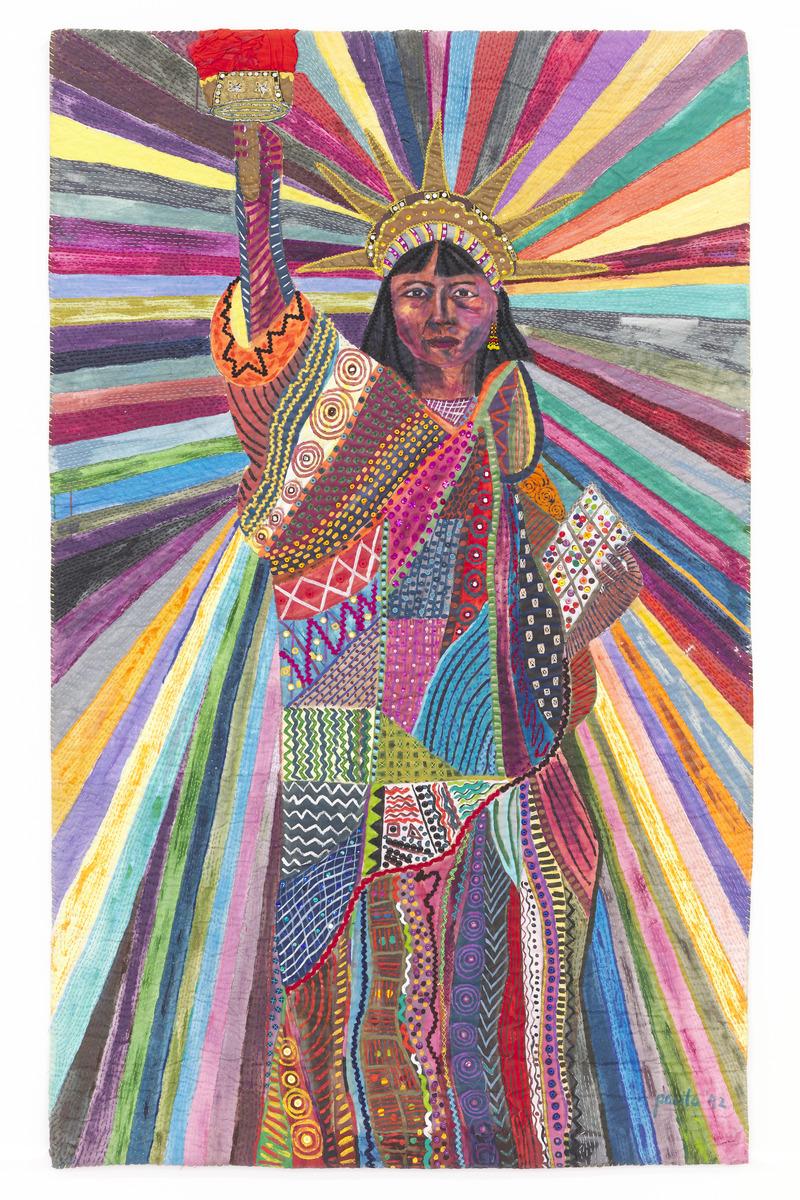

Pacita Abad, L.A. Liberty, 1992. Acrylic, cotton yarn, plastic buttons, mirrors, gold thread, painted cloth on stitched and padded canvas. Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; T.B. Walker Acquisition Fund, 2022. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate and Spike Island, Bristol. Photo: Max Clure.

Abad’s husband, Jack Garrity, credits their inaugural trip from Turkey to the Philippines for igniting Abad’s passion for art and textiles. After the couple settled in Washington, DC, she began taking painting lessons.

Feeling limited when painting on canvas, Abad drew inspiration from the various textiles traditions she encountered to create her very own hybrid art form called trapuntos. The term comes from the Italian word trapungere which means “to embroider.”

Her trapuntos consisted of a painted canvas to which she added a cloth backing. She would stuff polyester between the two layers, adding a 3-D, quilted aspect to her works. It was Abad’s fellow artist and friend Barbara Newman, who created puppets and soft sculptures, who taught Abad how to stitch and stuff trapuntos. Abad’s trapuntos joined a wave of feminist artists from the 1960s to 1970s who aimed to reclaim stitching as a serious art form, rather than women’s domestic labour. Given Abad’s background and politics, trapuntos also disrupted the Western view that textile work from the Global South was cheap labour to be taken advantage of.

Trapuntos resemble a form of bricolage — art created from a diverse range of found materials. Abad incorporated her expansive textile and material collections into her works: handwoven cloth from the Philippines, mirrors from India, buttons from Indonesia, and much more. These works were also quite large, often spanning 5 meters by 2.5 meters, if not bigger.

Abad’s trapuntos were an explosion of colour, an aspect of the artist’s signature style that not only represented her upbringing in the Philippines, but also disrupted Western ideals of art. To Abad, colour was a unifying value across the diasporic communities she sought to represent in her work.

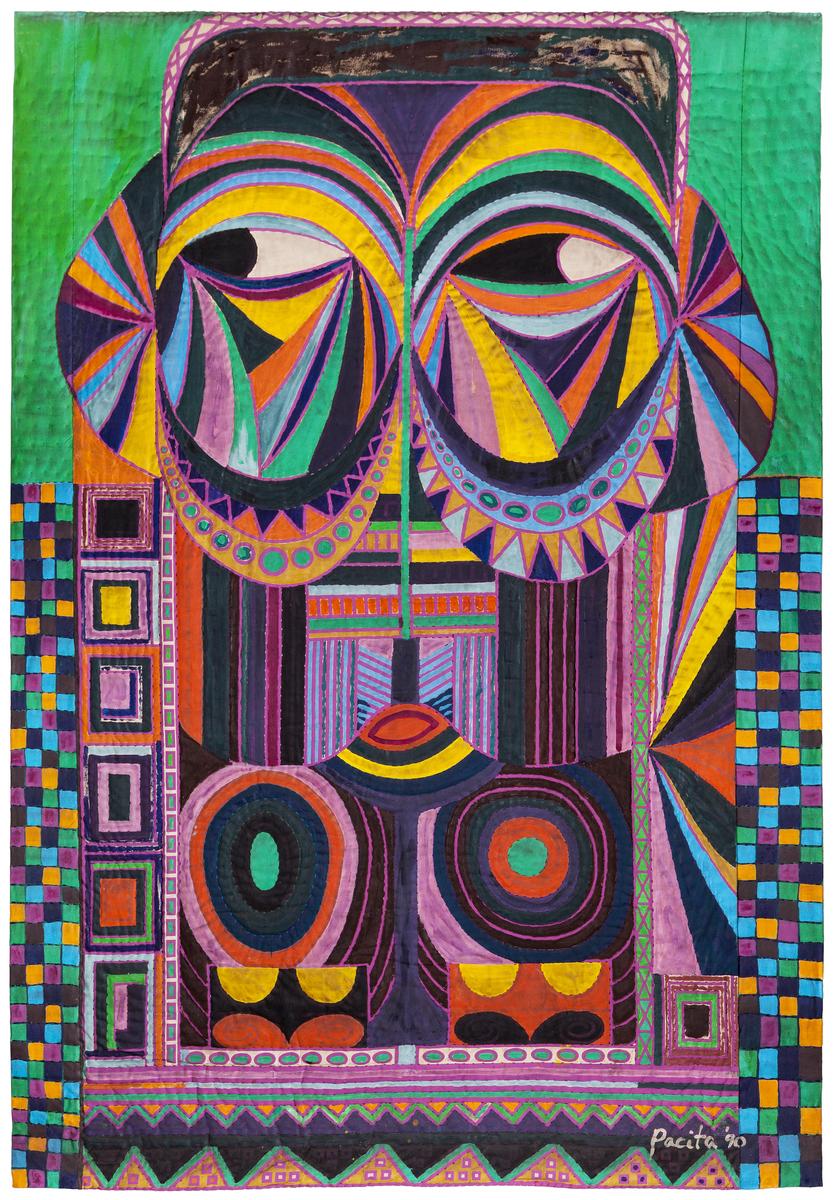

Pacita Abad, European Mask, 1990. Acrylic, silkscreen, thread on canvas. Tate: Purchased with funds provided by the Asia Pacific Acquisitions Committee 2019. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate and Tate. Photo: At Maculangan/Pioneer Studios.

Numerous trapuntos are on view in Pacita Abad, including European Mask (1990). This work is part of the larger series Masks from Six Continents, which was installed at the Metro Centre in Washington DC for three years. While the trapuntos representing Asia, Africa, Oceania, South America, and North America feature specific references to Indigenous cultures, European Mask seems disconnected from European culture. This work suggests that Europe is culturally uniform, lacking the vibrant diversity of other continents. In this series, Abad gives Europe the same treatment it provides non-European art, brushing the entire continent under the term “European” in the title of this work.

You’ll notice that the eyes in European Mask dart to the left. In the original installation of Masks from Six Continents, the eyes of European Mask look upon the rest of the trapuntos, likely a nod to Europe’s global colonization and perhaps representing an envy of the vibrant cultures on other continents.

4. She attended her exhibition opening in scuba gear.

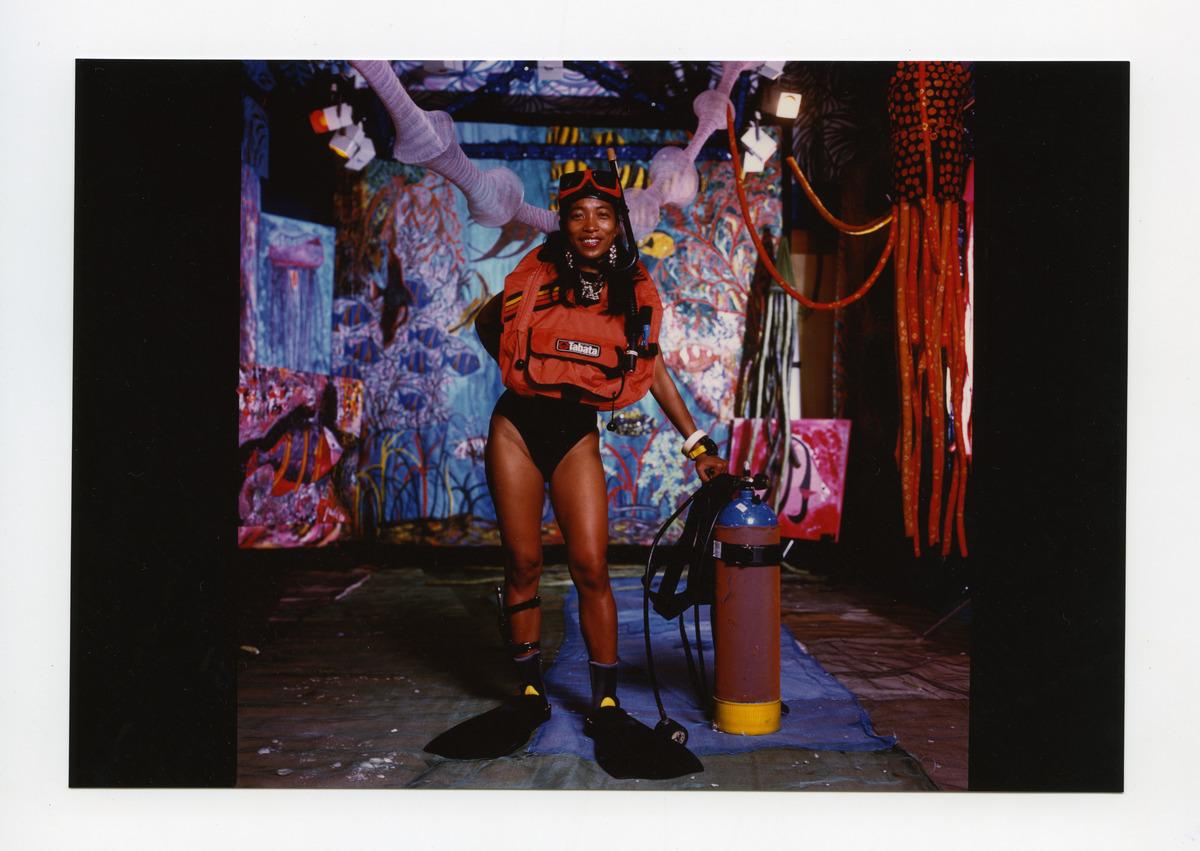

Pacita Abad in scuba gear, at the opening of her exhibition Assaulting the Deep Sea at the Ayala Museum, Makati, Philippines, 1986. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate. Photo: Wig Tysmans.

“She scandalized museum goers by… posing in the middle of her exhibit in a bathing suit complete with scuba gear,” read a review of Abad’s exhibition Assaulting the Deep Sea.

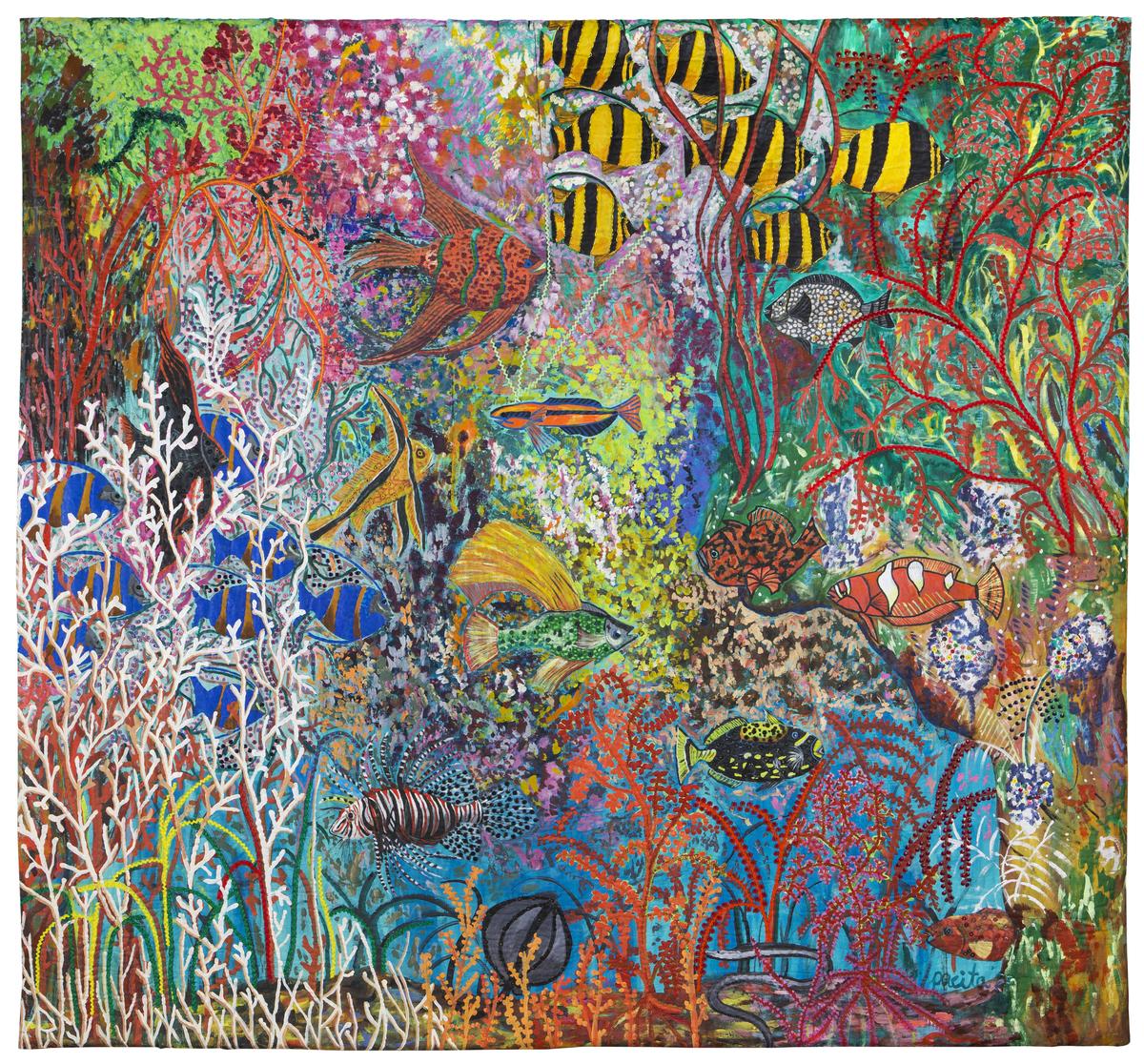

Abad learned how to swim as an adult after a near-drowning experience as a child left her petrified of the ocean. She took lessons at her local YMCA for three years before facing her fear of the ocean in Thailand. Instantly falling in love, she began learning how to scuba dive. Her diving adventures in Thailand and the Philippines inspired her deep-sea paintings created between 1985-1990, many of which were trapuntos.

Pacita Abad. My Fear of Night Diving, 1985. Oil, acrylic, cotton yarn, broken glass, plastic beads, buttons on stitched and padded canvas. Lopez Museum and Library, Manila, Philippines. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate and Lopez Museum and Library.

Her exhibition of these underwater works was truly immersive. Abad transformed the Ayala Museum in Makati, Philippines into a deep-sea experience for guests. She used mirrors and moving dyed cheesecloth to simulate the movement of water, filled the floor with sand and seashells, and hung soft-cloth sculptures of octopuses and squid on the ceiling. To top it all off, Pacita arrived in her scuba gear including her oxygen tank, flippers, and snorkel.

Pacita Abad. Anilao at its Best, 1986. Oil, acrylic, mirrors, plastic buttons, rhinestones on stitched and padded canvas. Courtesy of Pacita Abad Art Estate and MCAD Manila. © Pacita Abad Art Estate LLC.

Abad’s artistic practice was intrinsically tied to her identity, experiences, and passions, the exhibition of Assaulting the Deep Sea being just one example of how she blurred the line between art and life. This can also be seen in how she poses with her artwork. Not merely standing beside her trapuntos for documentation, she engages with them. In each photo, Abad embodies her work on display, almost becoming a singular entity with her art.

At the AGO, Pacita Abad features a room dedicated to works from Assaulting the Deep Sea, including aspects that pay homage to the immersive environment Abad insisted on.

5. She painted a 55-meter-long bridge while undergoing radiotherapy treatments.

Pacita Abad painting Alkaff Bridge, Singapore. Courtesy of Pacita Abad Art Estate. Photo © Michael Liew

In 2001, Abad visited Myanmar for six weeks, began building a studio and home in her native province Batanes, became an artist-in-residence in Sweden where she was learning to paint glass, and created three commemorative murals to 9/11 in New York.

It was also during that year that Abad was diagnosed with advanced lung cancer.

At the time, Abad’s home base was in Singapore, and she returned to undergo chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Neither her diagnosis nor her active treatments stopped her from pursuing new projects.

She created her last series of trapuntos called the Endless Blues. She took on another residency in 2003, this time at the Singapore Tyler Print Institute (STPI) created by American printmaker Kenneth Tyler. It was here, after a cup of coffee, that Abad got the idea to transform the Alkaff Bridge from its dreary grey battleship appearance to a colourful Abad masterpiece.

Pacita Abad painting Alkaff Bridge, Singapore. Courtesy of Pacita Abad Art Estate. Photo © Michael Liew

A believer in community art projects, Abad was already working with the government to make and promote public art across Singapore. For Abad, this ambitious art project seemed like a natural “gift” to leave Singapore.

Inspired by her STPI project Circles in My Mind, Abad and her team took upon her largest project, transforming the bridge into a multi-colourful statement featuring 55 colours and 2,300 circles. Abad did all this while undergoing her radiotherapy treatments in the last year of her life.

The Alkaff Bridge, now known as Art Bridge, was inaugurated in late January 2004, and has since become a symbol for Philippine-Singapore relations.

Calling it a public sculpture, Abad shared in her book Pacita’s Painted Bridge:

“My hope is that when people look at the fifty-five colours and playful circle designs adorning the Bridge, they will smile and enjoy experiencing art as a part of their daily life… I believe art should be for everyone, and that is why I am so happy that each day, thousands of Singaporeans and international tourists pass over, by and under the Bridge by foot, bicycle, car, bus, and boat.”

Pacita Abad painting Alkaff Bridge, Singapore. Courtesy of Pacita Abad Art Estate. Photo: Jack Garrity

After the completion of Artbridge, Abad returned to the Philippines for her final exhibition, Circles in My Mind, highlighting work from her STPI residency. Returning home to Batanes one more time, she completed her final paintings before her rapidly deteriorating health forced her to return to Singapore.

Abad passed away on December 7, 2004, after battling cancer for three years. She was laid to rest in the studio and home she and Garrity created in Batanes, fittingly named Fundacion Pacita.

Pacita Abad in her Bangkok studio, 1979, with the painting Floating Market (1978) in the background, at right. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate.

Abad was truly a force to be reckoned with, experiencing as much of the world as possible and becoming a voice for the marginalized.

Experience the bold, colourful, and daring art and life of Pacita Abad in Pacita Abad, on view at the AGO on Level 2 in the Sam & Ayala Zacks Pavilions (galleries 244 and 245). Organized by the Walker Art Center in collaboration with Abad’s estate, the exhibition is curated by Victoria Sung, Phyllis C. Wattis Senior Curator at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), and former associate curator, Visual Arts, Walker Art Center; with Matthew Villar Miranda, curatorial associate at BAMPFA, and former curatorial fellow, Visual Arts, Walker Art Center. The AGO presentation is organized by Renée van der Avoird, Associate Curator, Canadian Art.