Pacita Abad’s multi-textured Immigrant Experience

Take a closer look at three works from one of Abad's most personal series

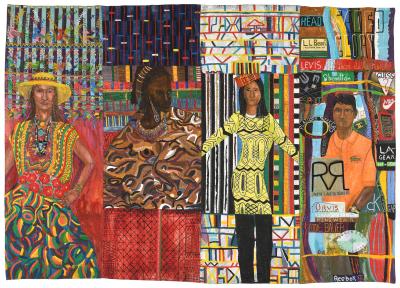

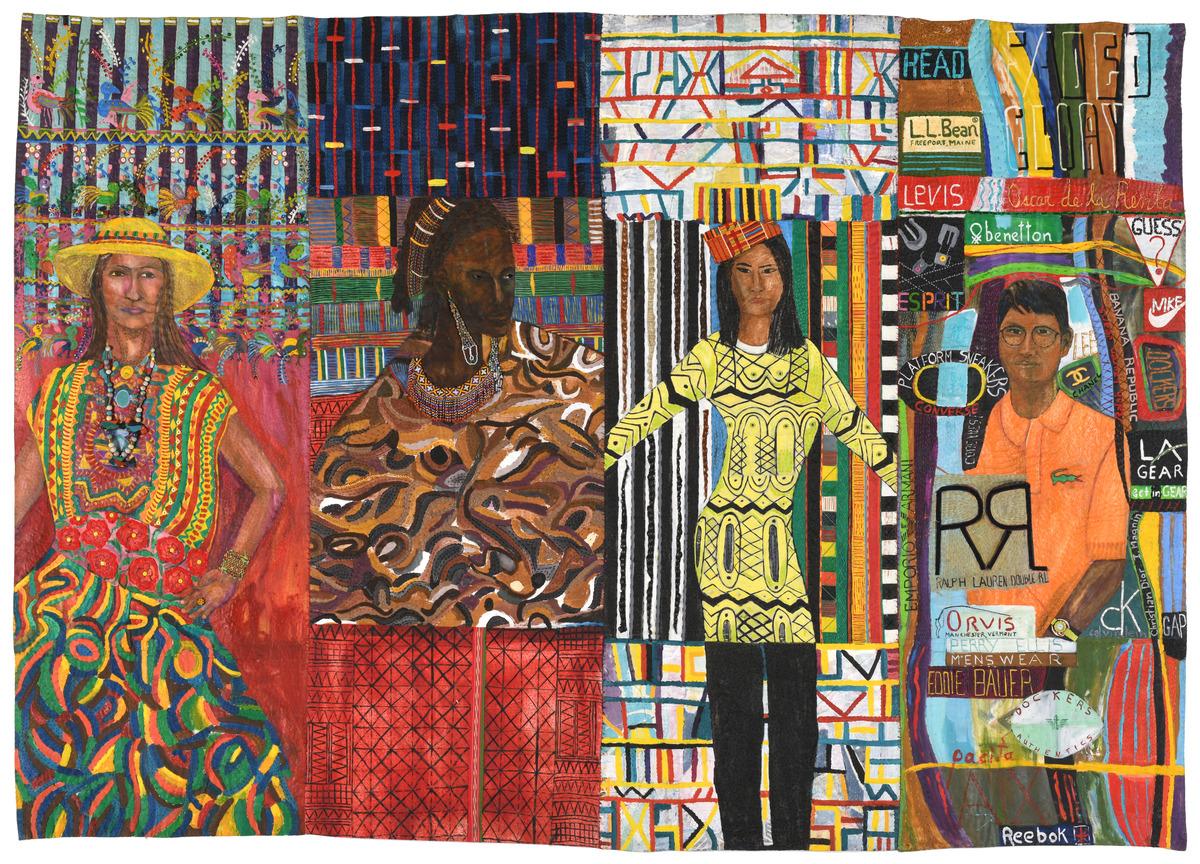

Pacita Abad. Cross-cultural Dressing (Julia, Amina, Maya and Sammy), 1993. Oil, cloth, plastic buttons on stitched and padded canvas. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate and Spike Island, Bristol. Photo: Max McClure.

In 1970, Filipina artist Pacita Abad (1946 - 2004) landed in San Francisco, marking the first time she left the Philippines.

Abad was forced to leave after she became a target for organizing student protests against Philippine dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Initially, her plan was to further her law studies in Spain, with a stop on the way to visit her aunt in San Francisco. However, Abad chose to remain in the city, embracing the hippie style of the time and finding work as a seamstress and part-time typist. She also began her graduate studies at Lone Mountain College.

While Abad’s appreciation for global cultures is often discussed alongside her international travels, her early time in America was crucial for expanding her worldview. It was in San Francisco that Abad first encountered people and cultures from around the world, including her fellow immigrants whom she honours in one of her most personal series, Immigrant Experience.

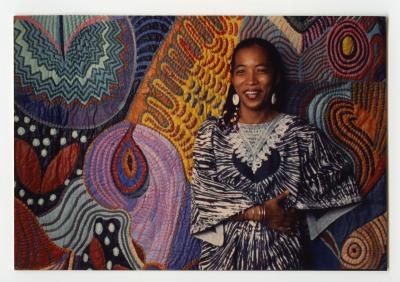

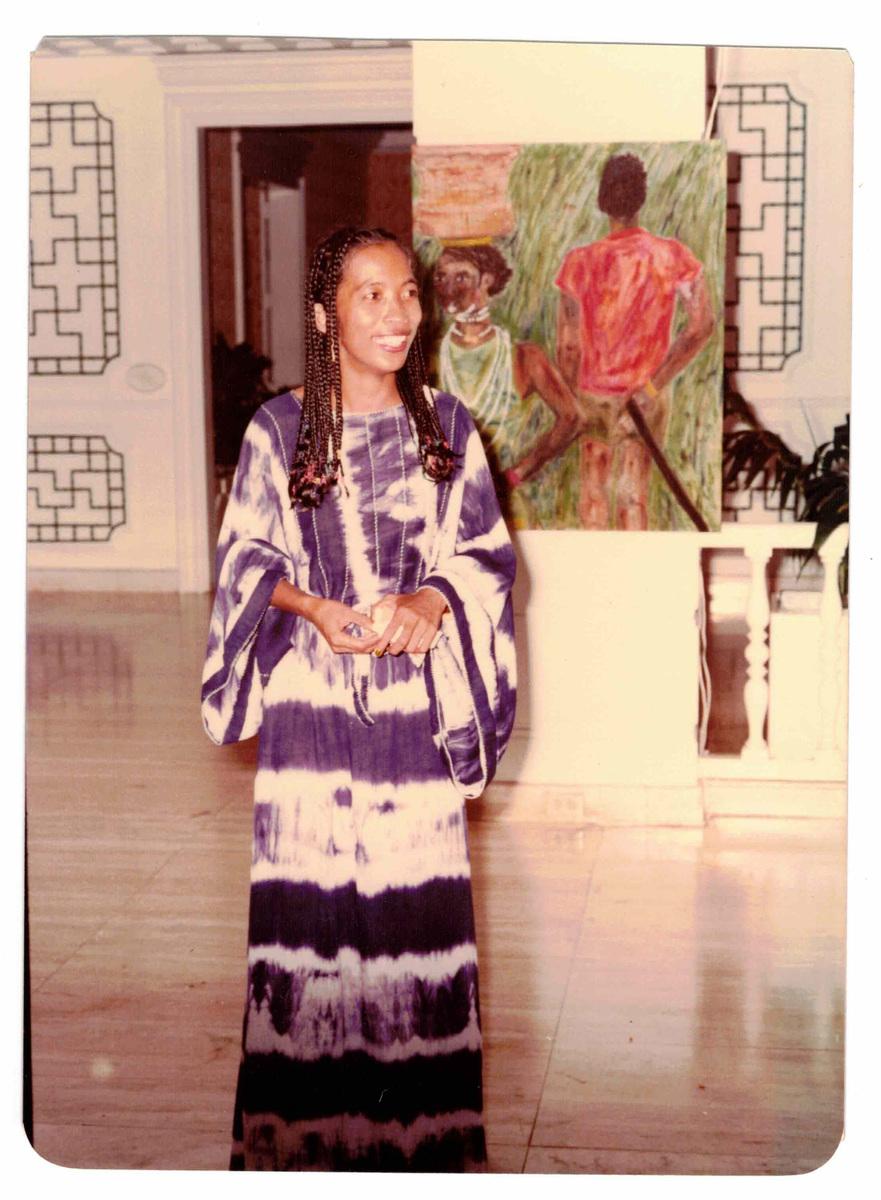

Pacita Abad at the opening of the exhibition The People of Wau at the Oriental Hotel, Bangkok, 1979. The artist wears a tie-dyed dress from Nairobi, Kenya. Her painting Abuk and Tong (1979) is visible behind her. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate.

Currently on view at the AGO, the exhibition Pacita Abad marks the debut of Abad’s work in Canada. It features over 100 works ranging in mediums by the artist alongside ephemera documenting Abad’s vibrant life. A selection of trapuntos — a hybrid, textured-based art form created by the artist — from Immigrant Experience are on view as part of the AGO’s presentation.

Consisting of around 20 trapuntos, Immigrant Experience explores the multifaceted yet interconnected experiences of immigration around the world, centring the stories of refugees, economic migrants, and both legal and undocumented immigrants.

Abad began the series after returning to America from a year-long international trip. Her time abroad led her to further appreciate the diversity of America. Inspired by the immigrants she met in San Francisco and later in Washington, D.C., Abad learned that many of them, like her, were political refugees or victims of American proxy wars. She came to understand the interlinked struggles of what she called the “uncelebrated” immigrants: people of colour from Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Through Immigrant Experience, Abad decided to make their overlooked stories visible.

In honour of this personal series, learn more about three works from Immigrant Experience that are currently on view at the AGO as part of the exhibition Pacita Abad.

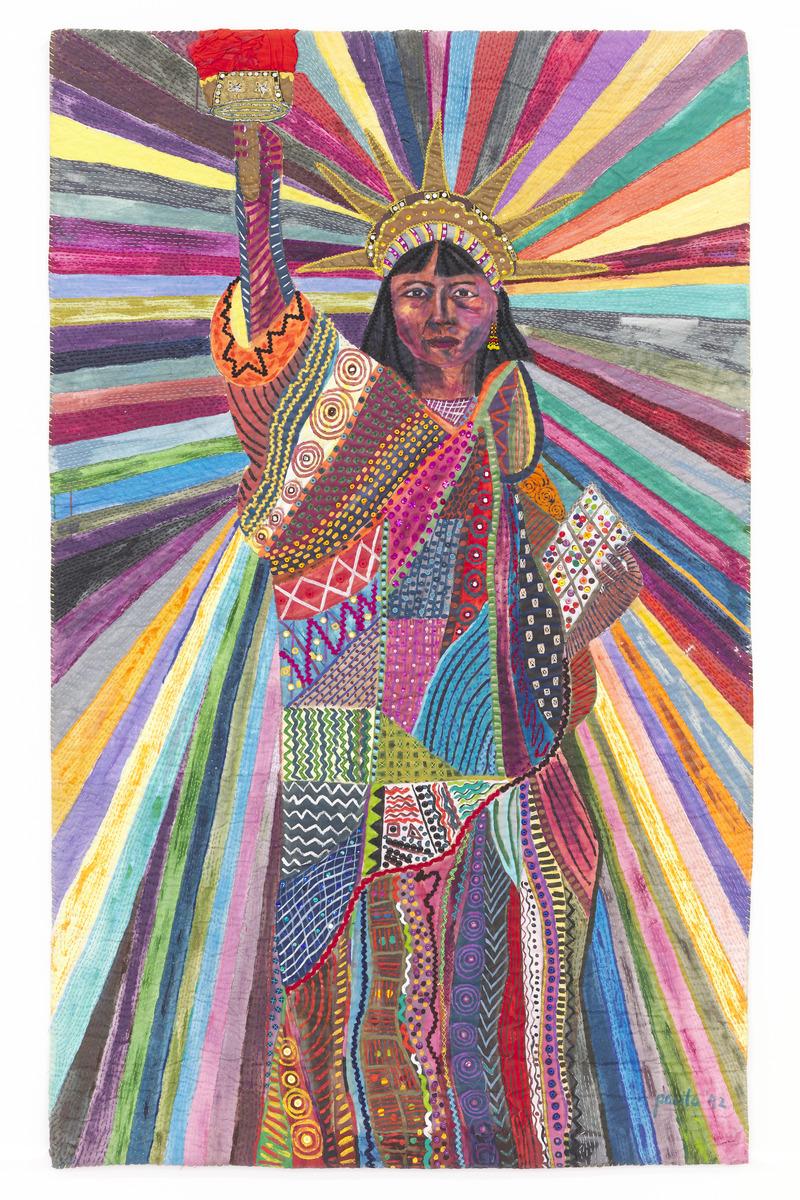

L.A Liberty (1992)

Pacita Abad, L.A. Liberty, 1992. Acrylic, cotton yarn, plastic buttons, mirrors, gold thread, painted cloth on stitched and padded canvas. Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; T.B. Walker Acquisition Fund, 2022. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate and Spike Island, Bristol. Photo: Max Clure.

When Abad decided to create Immigrant Experience, her first stop was Ellis Island, a historic immigration port that has become a monument to the American dream. During her visit, she could only find stories from European immigrants.

Understanding that immigrants from the Global South would enter America through southern and western borders rather than Ellis Island, she went looking for an equivalent monument. The closest she found was the Immigration Station on Angel Island, which was used to detain and interrogate over one million Asian immigrants.

Dissatisfied with the omission of non-European immigrants from American monuments, Abad created her own: L.A. Liberty (1992). This reimagining of the Statue of Liberty celebrates immigrants from the Global South while addressing the unequal treatment they face when arriving and living in America. This work is specifically dedicated to Asian and Latin American immigrants. The L.A. in the title stands for both Los Angeles and Latin America.

In L.A. Liberty, Lady Liberty is a proud, brown-skinned woman. For Immigrant Experience, Abad often asked friends and acquaintances to model for her works. In L.A. Liberty, her Filipina-Chinese friend Miriam Vermeiren was the model.

Abad’s Lady Liberty dons a vibrant, multi-coloured patchwork robe featuring buttons, tiny mirrors, and multicolour sequins. The vibrant robe represents the diverse ways immigrants from the Global South have contributed to the fabric of American society. While this version of Lady Liberty also holds a torch, Abad purposefully omitted the flame portion to symbolize how liberty’s light does not shine as brightly for non-European immigrants. A kaleidoscope of colour bursts from the figure's crown and fills the background of the work.

Abad’s lively depiction of the real-life monochromatic statue is reminiscent of her answer when asked what she has contributed to American art: “Colour, I have given it colour!”

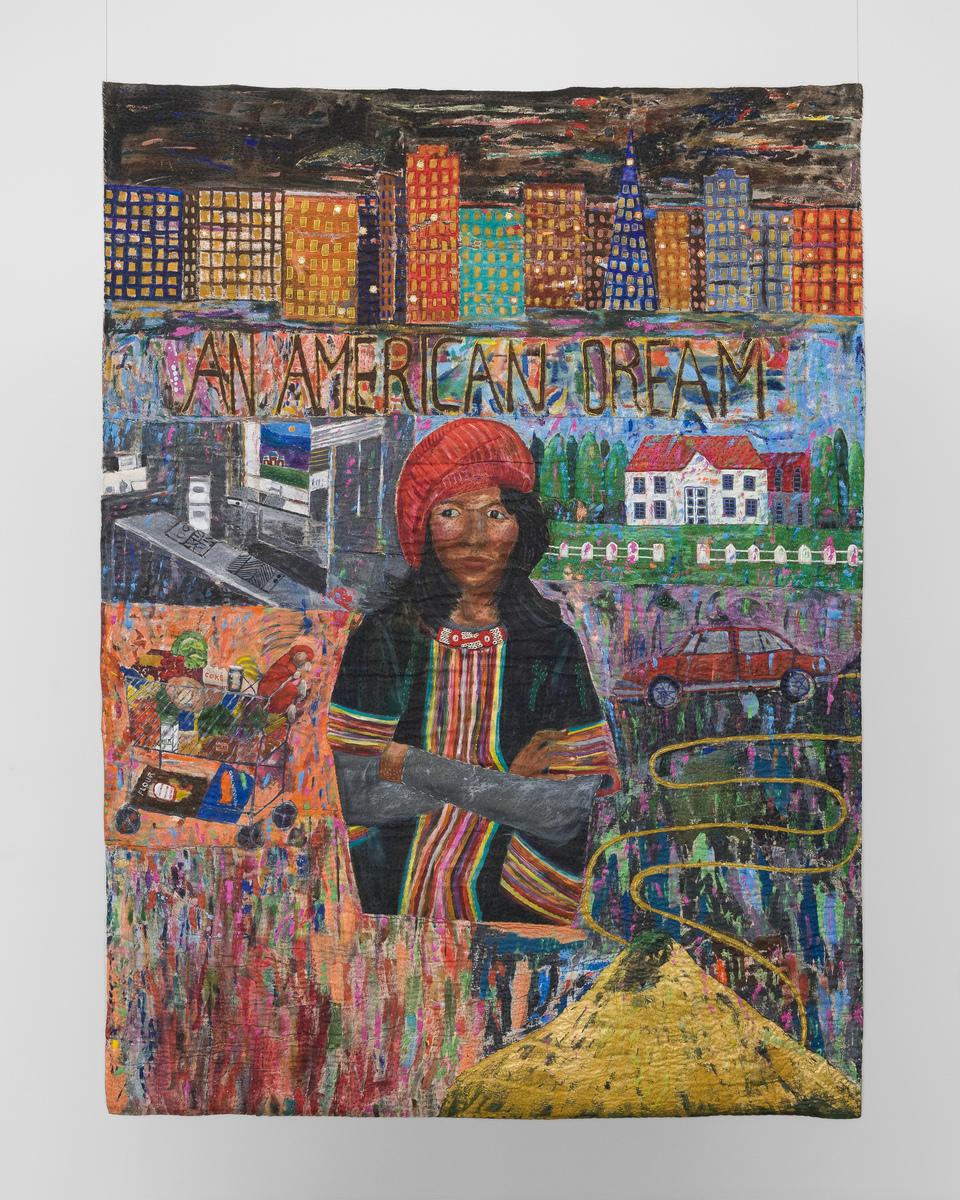

If My Friends Could See Me Now (1991)

Pacita Abad, If My Friends Could See Me Now, 1991. Acrylic, painted canvas, gold yarn on stitched and padded canvas. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Purchase, by exchange, through a gift of Peggy Guggenheim. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate and Tina Kim Gallery. Photo: Charles Roussel.

Likely a self-portrait, If My Friends Could See Me Now (1991) features Abad wearing a Guatemalan huipil and a red beret. She’s positioned in the centre of vignettes representing the American dream: a house with the white picket fence, a kitchen equipped with appliances, a grocery cart filled with endless groceries and a baby, a city skyline under a dark sky, and a car driving on roads paved with gold.

This trapunto tells the story of immigrants who were able to pursue higher education and built what can be deemed as “successful” lives through the lens of the American dream. While it’s likely a self-portrait, in the book Immigrant Experience, Abad’s husband Jack Garrity speaks about Abad’s friend Than Lo when reflecting on If My Friends Could See Me Now.

Than Lo immigrated from Vietnam to America in the 1970s and married her husband, an immigrant from Laos. The pair were able to earn their graduate degrees, work professional jobs, and buy a house in the suburbs for their family.

Than Lo’s family in Vietnam lived a very different reality. Released from a communist re-education camp, her family barely survived fleeing to a refugee camp in Malaysia. Eventually, Than Lo was reunited with her family after they immigrated to America. While not necessarily idealizing nor villainizing the American Dream, If My Friends Could See Me Now is an example of how Abad’s series captures the complicated realities of immigrating to America.

Filipina: A Racial Identity Crisis (1990)

Pacita Abad. Filipina: A Racial Identity Crisis, 1992. lithograph with pulp-painted chine collé and metallic powder on paper, edition of 40. Courtesy Pacita Abad Art Estate. Photo Rik Sferra for Walker Art Center.

Alongside Abad’s experiences as an immigrant, Immigrant Experience also examined the artist’s Filipino roots and identity, as well as the realities of Filipino migrant workers.

Filipina: A Racial Identity Crisis (1990) examines how the Spanish colonization of the Philippines has created a divide in Filipina identity. Abad split this work down the centre to examine the tension between two Filipina archetypes.

On the left is Maria Isabel Lopez, who is fairer-skinned, has a Spanish name, and is dressed in a Maria Clara-style terno, which is often made from pineapple fibre, a fabric introduced by Spanish colonization. Around her neck is a rosary-styled necklace called a tamborin, symbolic of how the Spanish brought Catholicism to the Philippines.

On the right is darker-skinned Liwayway Etnika, who bears a Tagalog name and is dressed in Indigenous textiles. She wears a malong (waist wrap) closely resembling fabrics created by Indigenous Filipino weavers and a brightly coloured patterned top.

The dualism of these two archetypes examines how Spanish colonialism has impacted Filipino culture and created ethnic and class divisions. Maria Isabel Lopez represents how colonizer culture has become linked to elite classes in the Philippines. The work also touches on how colourism has become adopted within Filipino culture. Yet, Abad gives both women equal space, emphasizing the importance and value of Indigenous Filipino culture and features.

It’s no surprise which woman Abad saw herself in: “As you may have guessed, I lean more towards the tribal Filipina,” she shared in Abstract Emotions, an unpublished text by the artist.

—

Many more trapuntos from Immigrant Experience are on view in Pacita Abad, on view at the AGO until January 19, 2025, on Level 2 in the Sam and Ayala Zacks Pavilion (galleries 244 and 245).

Organized by the Walker Art Center in collaboration with Abad’s estate, the exhibition is curated by Victoria Sung, Phyllis C. Wattis Senior Curator at Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive (BAMPFA), and former associate curator, Visual Arts, Walker Art Center; with Matthew Villar Miranda, curatorial associate at BAMPFA, and former curatorial fellow, Visual Arts, Walker Art Center. The AGO presentation is organized by Renée van der Avoird, Associate Curator, Canadian Art.