A journey into sound with Wendel Patrick

The accomplished musician and professor reflects on creating The Culture’s hip hop soundscape

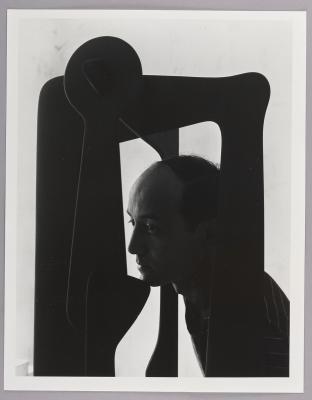

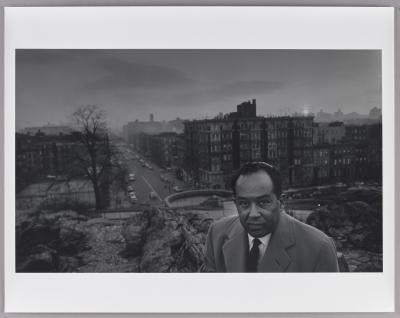

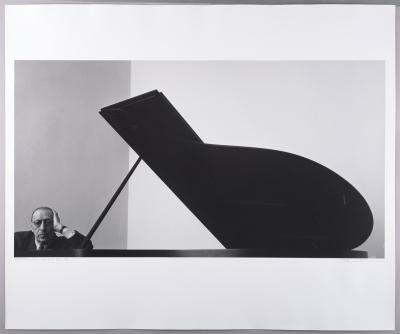

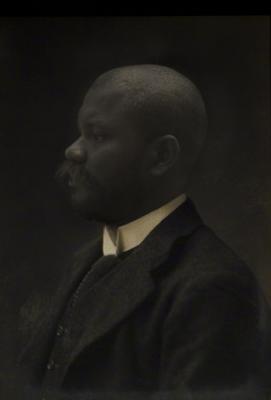

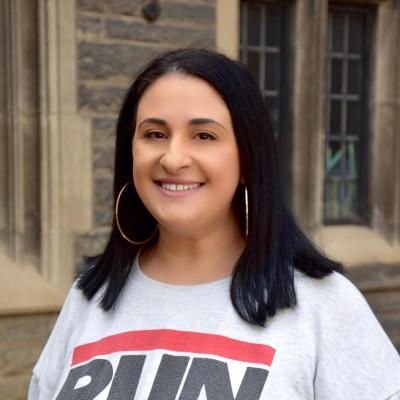

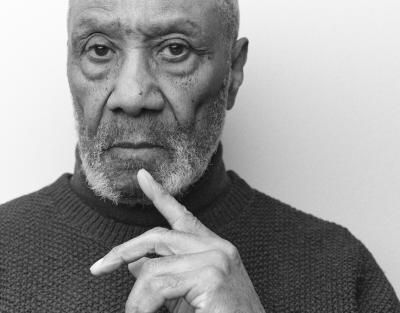

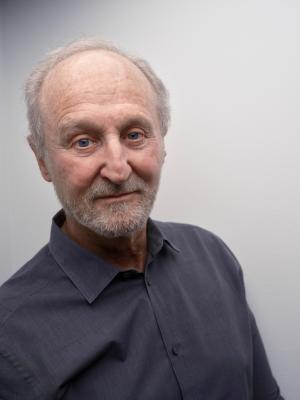

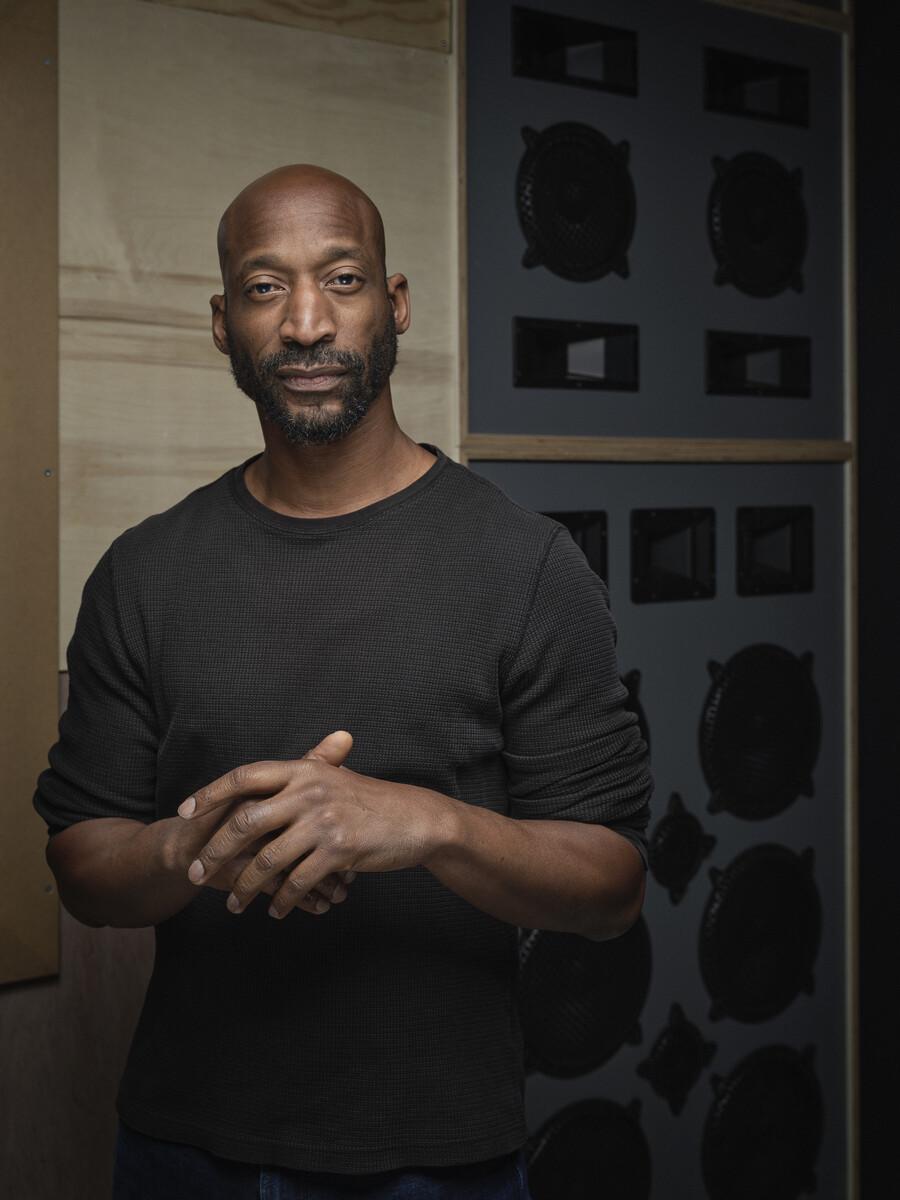

Wendel Patrick. Photo: Craig Boyko © AGO

When the Baltimore Museum of Art approached musician and professor of hip hop Wendel Patrick to collaborate on creating an original soundscape for a hip hop-themed exhibition, he knew he was a perfect candidate. The Washington D.C. native is a classically trained pianist who grew up entrenched in hip hop culture during the 80s and 90s. Along with his collaborator and fellow Baltimore-based musician-producer Abdu Ali, Patrick mixed and reinterpreted hip hop’s greatest artists and influences with ambient sounds and references to Baltimore house music, creating a distinct auditory atmosphere for the exhibition’s debut presentations.

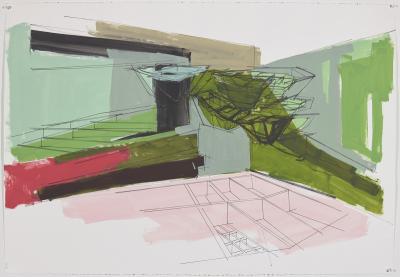

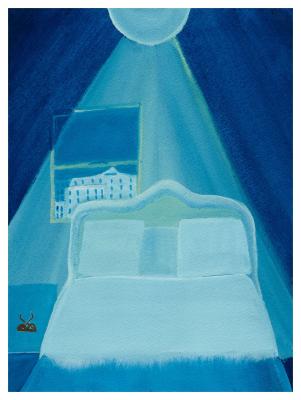

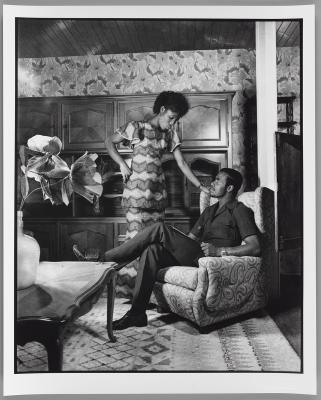

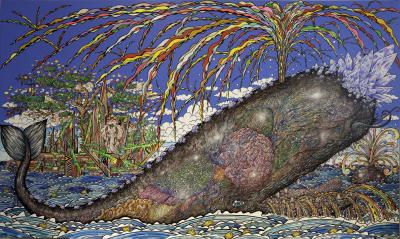

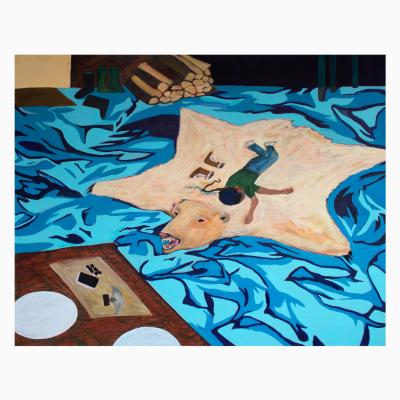

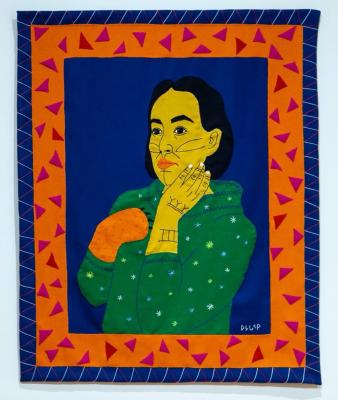

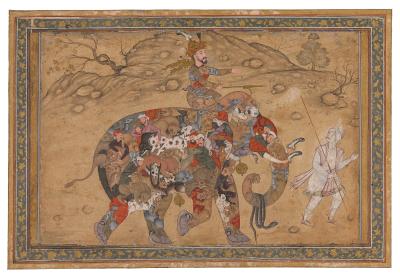

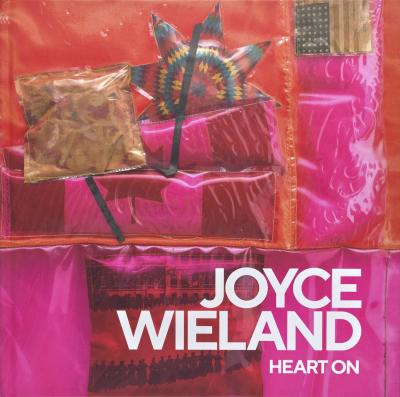

When the exhibition headed north to make its Canadian debut at the AGO, the museum approached Patrick to craft a second version of the soundscape, this time showcasing the roots of Toronto hip hop. His new rendition, along with ephemera and artworks from over 30 acclaimed artists, is featured now at the AGO as part of the exhibition The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

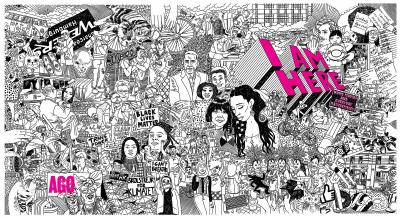

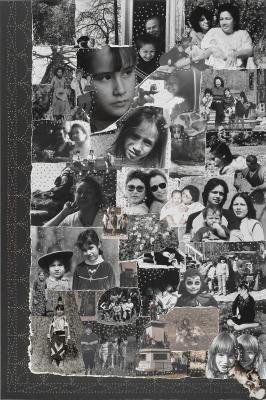

Patrick’s soundscape weaves together a collection of staple songs from hip hop’s first 30 years, using a pastiche of self-produced interpolations and abstractions. Imagine moving through an exhibition space, looking at replicas of wigs worn by Lil Kim, while hearing MC Lyte’s Paper Thin transition into an orchestral arrangement of Fall in Love by Slum Village. Or witnessing Patrick Nichols's epic portrait of 100 Canadian hip hop figures, while the Toronto classic Let’s Ride by Choclair blends into the Q-Tip song of the same title. It’s a complex sonic language, dense enough for hip hop heads yet fun enough for new listeners. The roughly 30-minute-long soundscape plays on a loop throughout every gallery in the exhibition. Visitors are also able to continue listening after they leave with The Culture’s AGO-curated Spotify playlist featuring 20 songs inspired by the exhibition.

Wendel Patrick is an award-winning polymath musician and composer. He has released five self-produced albums (Sound, Forthcoming, JDWP, Passage, and Travel) and toured widely, collaborating with a range of artists including poet Ursula Rucker and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra. He is an Associate Professor at The Peabody Music Conservatory – Johns Hopkins, where he teaches the course “Hip Hop Music Production: History and Practice.” It has recently been developed into the first-ever Bachelor of Hip Hop Performance degree program, which Patrick will be directing.

Patrick spoke to Foyer about his lifelong relationship with music production, his approach to building soundscapes, and what he hopes to impart on his students as a professor of hip hop.

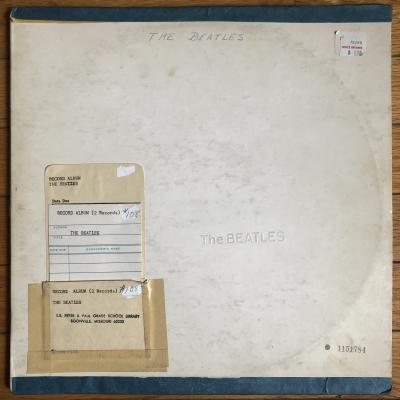

Foyer: This soundscape contains a wide range of songs and artists, from Rakim and Eric B to Bone Thugs-N-Harmony to Suite for Ma Duke's Orchestra. Can you walk us through some of your process for deciding what songs to include?

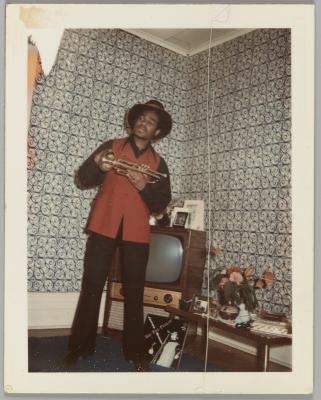

Patrick: The way I select the songs begins intuitively, then it grows from that initial seed. The order then progresses based on a number of things, including tempo and thematic lyrical content. I love all music, and one of my favorite things about hip hop is how musical it is. I wanted to pay tribute to some of the very early and important contributors to hip hop. Many of them are influences from my childhood and teenage years.

When listening to the soundscape, you’ll hear well-known songs that contain recognizable samples and you’ll also hear the original sources of those samples, specifically the sections that come before or after the part used in the popular song. This is a big part of the sonic fabric of hip hop. Thinking about hip hop production, this is all source material that has been built on and has also shifted and changed over time. Suite for Ma Dukes is a perfect example. It’s from Miguel Atwood-Ferguson's orchestral arrangement of one of the most influential hip hop beat makers of all time [J Dilla]. In the soundscape, I also used a cover of Bone Thugs-N-Harmony’s Crossroads, which I made. It’s all me playing various virtual instruments, but it’s made to sound like a jazz quartet, which is a nod to - and a unique expression of - the source material.

How much Toronto hip hop were you aware of before working on this project? Can you share some favorites that you discovered and why you wanted to include them?

This has been an awesome period of discovery for me. When I was first approached about doing this soundscape and asked about including a Toronto hip hop element, I viewed it as an opportunity to learn. I went down my own rabbit holes of research, but I also asked the curatorial team at the AGO for recommendations.

These days there's so much information at everybody's fingertips about who an artist is and where they’re from, but back in the day it wasn’t really like that. You might hear someone rhyming in dancehall or dub style and just assume they were Jamaican. We’d often hear songs mixed back-to-back on college radio, then they’d announce the artists but you wouldn’t know who was who. So, there were several Toronto hip hop songs I knew, but just wasn’t aware the artists were from Toronto. I probably assumed they were from elsewhere. Then there were other Canadian hip hop songs and artists I knew all about.

I was a really big k-os fan in the early 2000s. I remember going to see him at the 930 club in D.C. When I was in high school, Snow’s Informer was all over the radio. I had heard some of Kardinal Offishall’s music, but didn’t know he was from Toronto, but I could always hear the patois in his vocals. It was also interesting hearing earlier Maestro Fresh Wes and Michie Mee music, which reminded me that Toronto hip hop has representation in all of hip hop’s time periods.

I ended up listening to a lot of the music I discovered even after the soundscape was done. I now have an exclusively Toronto hip hop playlist that I listen to often.

Can you share some of your technical approach to building a soundscape? How do you make it cohesive? How do you decide when to play a song in full, versus adding an interpolation or an abstraction?

I'm a composer. I like to approach pretty much everything I do production-wise like a composer would. In the soundscape, there are almost no songs that play all the way through, because I wanted it to play like a DJ mix. That gives me a chance to pair certain songs or break elements of a song apart and pair them differently. The only song that plays all the way through is a rendition I made of Hotline Bling, where my goal was to explore a different sonic aesthetic than the original. I look at each song I add to the soundscape like a unique challenge. The way I incorporated Snow’s Informer starts with a 2018 remix of the song, then it moves into a hard-hitting original production I made, then it shifts into something else that is very unexpected - which I will keep as a surprise for visitors. These are all just opportunities to explore beyond how people typically think about sonic possibilities.

All the interpolation sections in the soundscape are performed by me, mostly on virtual instruments and software that I can craft and sculpt. I may adjust kick and snare drums, or change the tuning of an upright bass. I want the soundscape to feel cohesive , but also give the listener time and space to process what they’re hearing and the many juxtapositions throughout the mix. It's all designed to have the listener be a participant in the experience and then also, most importantly, to support what everybody is actually going to see in the exhibition.

Wendel Patrick. Photo: Craig Boyko © AGO

You are an associate professor at the Peabody Music Conservatory, where you direct of The Bachelor of Hip Hop Music degree program. Can you describe your approach to creating the curriculum and what you hope students will experience from taking the program?

I started teaching at the Peabody Music Conservatory in 2016. They gave me the freedom to create a brand new hip hip class of my own design. I ended up developing a history class, taught through a hip hop producer’s lens. The class was called Hip Hop Music Production: History and Practice. It was designed this way because, generally speaking, since the emergence of recorded hip hop, the major impact of the musical creators of the genre has been overshadowed by the vocal performers (rappers). In the class we talked about emcees, turntablists, beat boxers and many other elements, but all through the overarching lens of the hip hop producer. Over the years since the class began, the department has grown. There’s an upper level of the original class, a hip hop ensemble class, and others. These classes and other's I've designed will now serve as the basis for the first ever Bachelor of Music in Hip Hop performance degree. The program will have four primary disciplines: rap, turntablism, beatboxing and production, meaning students will be able to enroll as a hip hop major, specializing in one of those four disciplines.

I’ve learned so much about music and life through hip hop. I’m a classically trained jazz pianist, and learned that craft through traditional means. Hip hop production was totally different for me. I had to acquire knowledge and skill over time. As a young person, I had to slowly acquire pieces of digital music gear, which were expensive and hard to come by. I basically had to teach myself how to produce through studying the work of many other producers. The process of learning and improving took a long time, but was very rewarding and required a hands-on approach every step of the way. So, my hope for my students is the acquisition and honing of skill across these four disciplines, and learning from people who have acquired large amounts of skill along the way through the same kind of a process. Hopefully they can maintain that way of learning in a system and institution that isn't necessarily designed for that, but that can benefit from people who have this creative way of thinking.

Check out Wendel Patrick’s essay Hip Hop in Academia: Honouring the Past While Looking to the Future, as part of The Culture’s official exhibition catalogue on sale now at The AGO Shop on Level 1. The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century is currently on view on Level 5 of the AGO. The exhibition is co-curated by Asma Naeem, the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA)’s Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director; Gamynne Guillotte, the BMA’s Chief Education Officer; Hannah Klemm, Saint Louis Art Museum (SLAM)’s Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art; and Andréa Purnell, SLAM’s Audience Development Manager. The AGO presentation is organized by Julie Crooks, Curator, Arts of Global Africa and the Diaspora, AGO.