A short (brimmed) history of the trilby hat

Explore the creative life of one of Leonard Cohen’s signature accessories.

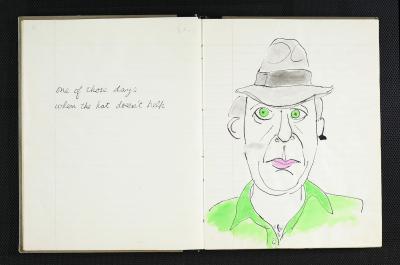

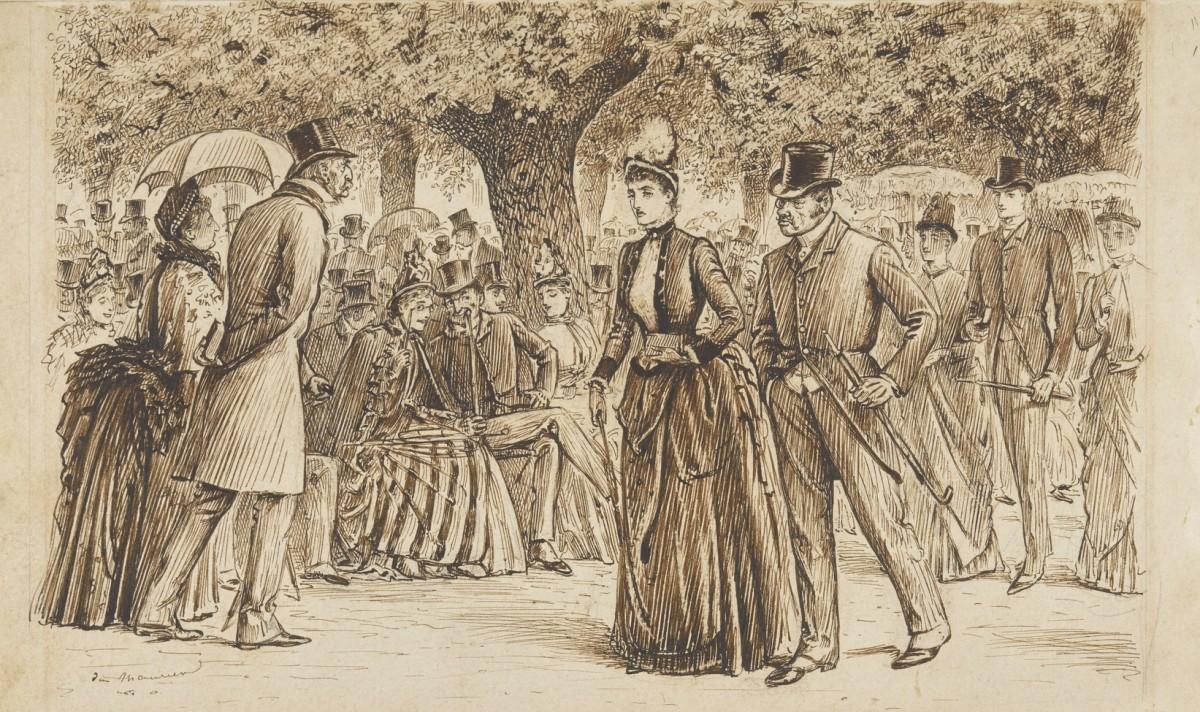

Leonard Cohen, One of those days (Watercolour Notebook), 1980-1985. Watercolour notebook. Overall: 21.1 x 32.5 cm. © Leonard Cohen Family Trust.

An intimate view of Leonard Cohen’s creative life as seen through his own archive, the exhibition Everybody Knows reveals much about the man – his influences and his output. It suggests a man in near constant motion, forever seeking the right words, the right place, the right kind of success. But spend enough time in the exhibition and it becomes clear that for all his material asceticism, Cohen was a man of specific tastes – prizing his typewriter, his sketchbooks, his guitar, and we discovered, his hats.

We counted 22 instances of the artist depicted wearing a hat throughout the exhibition – as a child shoveling snow in home movies, in a photo taken by his neighbour Hazel Field, in his sketchbooks, on album covers, in prayer and on stage. And what the chronology of the exhibition makes clear is that, during the last decade of his career, only one kind of hat would do: a dark wool or felt trilby, worn with a dark, double-breasted pinstripe suit. No tie.

If the hat makes the man, what then makes the trilby so appropriately Cohen? While not as commonplace nowadays, it is an object whose history and popularity are perhaps as literate and storied as the artist himself. The perfect choice for a man who allegedly claimed to have taught the poet Irving Layton how to dress. In recognition of Cohen’s sartorial taste, we here present a short, artfully biased history of the trilby hat.

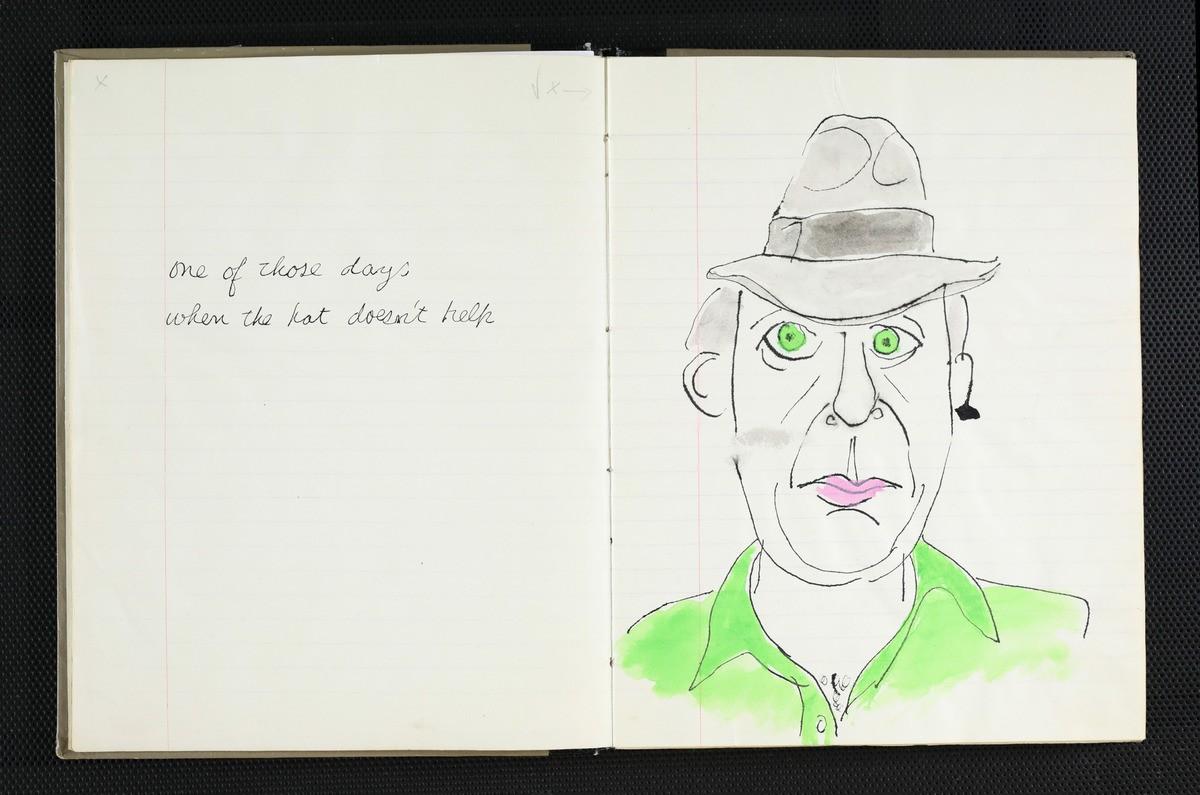

An uneven cross between a fedora and Tyrolean cap (and not to be confused with the pork pie hat beloved by jazz musicians like Lester Young), the trilby, according to Lock & Co Hatters (the world's oldest hat shop), is defined by its “short brim that is customarily turned up at the back and down at the front. A trilby is typically worn on the head either straight or slightly backward.” In the timeline of hats, the trilby is something of an ingénue and owes its invention to a best-selling novel by the French-born British writer and illustrator Georges du Maurier (1834-1896). To be clear – du Maurier didn’t invent the hat, just the book it was named after. In fact, the bulk of du Maurier’s career was spent drawing satirical cartoons for magazines like Punch, and this one, for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, from the AGO Collection.

George Louis Palmella du Maurier, Feminine Perversity: The Sunday Promenade in Rotton Row (for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine), 1887. Pen and brown ink on paper. Comprised of two sheets: 16.6 x 34.3 cm. Gift of the Trier-Fodor Foundation, 1981. Photo © AGO. 80/103.

The success of du Maurier’s novel Trilby, published in 1894, changed all that. Victorians couldn’t get enough of his scintillating tale of one woman's journey from orphan to opera star in Paris, thanks to the hypnotic powers of the evil Svengali. That woman’s name? Trilby O’Farrell. She doesn’t wear a hat in the book – she scandalously wanders barefoot and smokes. But when the book was adapted for stage by the American playwright Paul Potter in 1895, a new, appropriately rakish hat was invented for the occasion and quickly gained popularity among men and women alike. Unlike Cohen, du Maurier (grandfather of the novelist Daphne du Maurier) reportedly spent his remaining years begrudging his international success.

Now a mostly forgotten tale, Trilby informed a generation of writers. In his 1922 novel Ulysses, James Joyce has his main character Molly Bloom recalls in her closing monologue, seeing a performance of Trilby. “They're always trying to wiggle up to you,” recalls Molly, “that fellow in the pit at the pit at the Gaiety for Beerbohm Tree in Trilby the last time I'll ever go there to be squashed like that for any Trilby or her bare bum” (Joyce 1922, 717).

Skip forward two world wars, during which time Buster Keaton made a straw pork pie hat hilarious and Humphrey Bogart’s fedora reigned supreme, and suddenly, in 1958, who's wearing a trilby but ol’ blue eyes himself, Frank Sinatra, on the cover of his album Come Fly with Me.

Through the 1950s and ‘60s and into the ‘70s, the trilby was never fully in or out of fashion. For his role as the inept French Inspector Clouseau in A Shot in the Dark (1964), actor Peter Sellers donned a custom trilby. Subsequent Pink Panther films cast it aside however, in favour of a more Sherlock Holmes tweed bucket hat. It was 1980 before Jim Belushi and Dan Ackroyd put the trilby back onto the big screen as the R&B singing duo on a mission from God in the film The Blues Brothers.

The choice of a trilby for The Blues Brothers wasn’t purely aesthetic however, but an intentional nod to the style of soul, jazz and reggae musicians. At a 2021 exhibition at the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum in Coventry, UK, trilby hats again were very much front and centre, on view as part of an exhibition celebrating the cultural impact of the 2 Tone record label, and the eponymous musical genre they cultivated in Britain during the 1970s and ‘80s. A distinctive blend of Jamaican ska music, punk, blue beat, reggae and soul, 2 Tone bands included The Specials, The Beat and The Bodysnatchers. Wide-reaching, 2 Tone’s racially and musically diverse talent pool found mainstream success at a moment of widespread social unrest. These musicians, the so-called ‘rude-boys’, were identifiable, in the words of musician and label founder Jerry Dammers, by their “trilbys, bowler and pork pie hats…pinstripe suits, button-down shirts and checked scarves.”

{"preview_thumbnail":"/sites/default/files/styles/video_embed_wysiwyg_preview/public/video_thumbnails/074AfC9tw48.jpg?itok=6v7u6ZZZ","video_url":"https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=074AfC9tw48","settings":{"responsive":1,"width":"854","height":"480","autoplay":0,"title_format":"@provider | @title","title_fallback":true},"settings_summary":["Embedded Video (Responsive)."]}

Which, to come full circle, does sound a lot like Cohen during that final decade. We would be remiss (and hardly an art gallery) if we did not pause for a moment to consider the artistry of the hatmakers themselves. Once a hotspot for clothing manufacturing – Cohen was himself born into a family of clothing merchants – the tradition lives on in Montreal, courtesy of Canadian Hat 1918, an independent manufacturer where hats have been made by hand for more than 100 years.

Leonard Cohen: Everybody Knows runs until April 10, 2023, and is organized by the AGO with the exceptional support of the Leonard Cohen Family Trust and Musée d'art contemporain de Montréal.