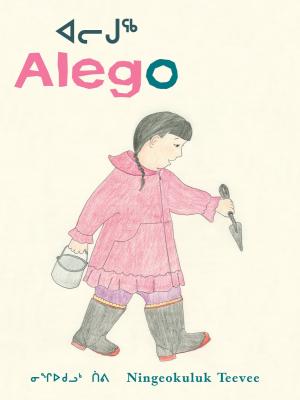

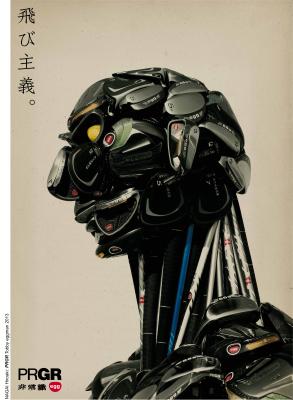

Constructing The Front Room with Michael McMillan

The Vincentian multidisciplinary artist unpacks his fascination with post-colonial front rooms

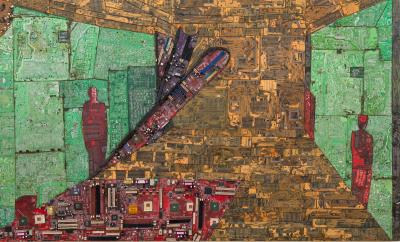

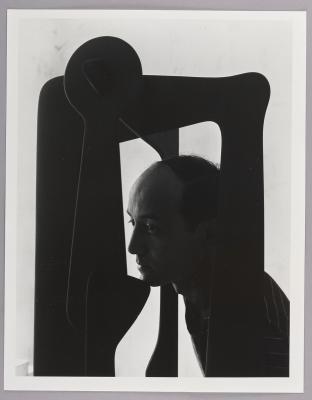

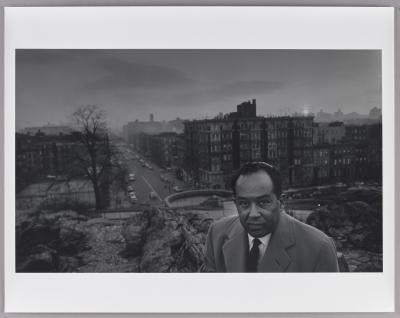

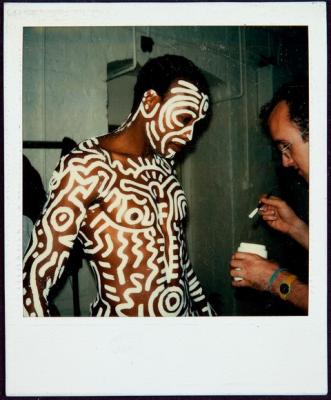

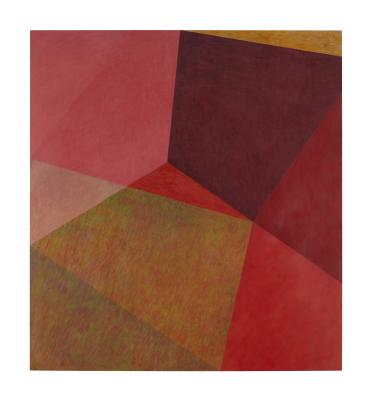

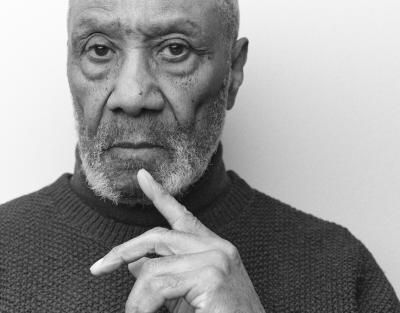

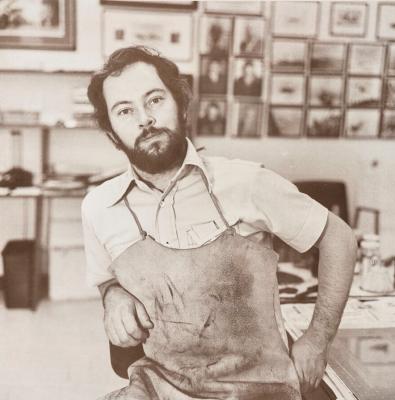

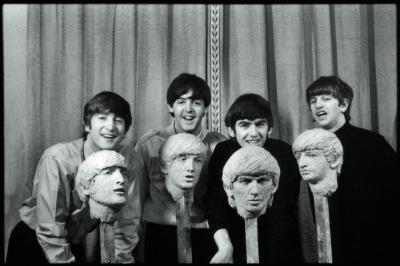

Michael McMillan in The Front Room: Inna Toronto/6ix, 2023, by Michael McMillan. Mixed media site-specific installation © Michael McMillan. Photo: Craig Boyko © AGO.

“I realized the front room was part of me and therefore worth exploring creatively.”

Acclaimed writer, playwright, artist and curator Michael McMillan arrived at this epiphany in 1998 while interviewing Caribbean elders for a project in his hometown of Wycombe, UK. At that moment, the universal aesthetic and powerful symbolic representation of post-colonial “front rooms” (specifically in Black and working-class communities) was revealed to him, giving way to what has become over 20 years of artistic exploration.

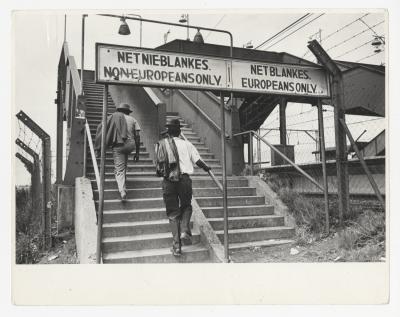

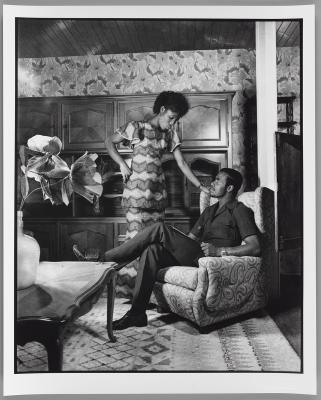

In 2005, his first major iteration of the installation, titled The West Indian Front Room: Memories and Impressions of Black British Homes, was unveiled at the Geffrye Museum, welcoming visitors into a life-sized, fully functional British-Caribbean front room set in the 1970s. Since then, the work has become part of the Geffrye’s permanent collection, and McMillan went on to construct iterations of The Front Room everywhere from South Africa to France.

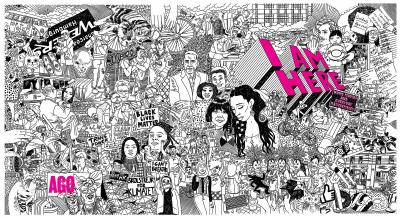

In 2021, a new version of the acclaimed work was added as an immersive centerpiece for the Tate Britain’s landmark exhibition, Life Between Islands Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now. After a successful run at the Tate, Life Between Islands has come to the AGO along with McMillan’s installation. On view now, The Front Room: Inna Toronto/6ix is the Toronto iteration of the series, based on a Caribbean-Canadian home in the 1980s.

The Vincentian multidisciplinary artist spoke to Foyer about front rooms, why they’re so important, and his journey with this epic series.

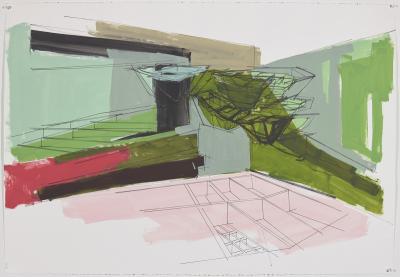

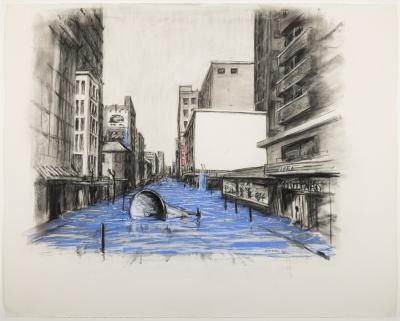

Michael McMillan, The Front Room: Inna Toronto/6ix, 2023. Mixed media site-specific installation © Michael McMillan. Photo: Sean Weaver © AGO.

Foyer: You created the first major iteration of The Front Room in 2005. What is the inception story of the work? Why was it crucial to you that it be an immersive installation?

McMillan: Growing up, I was fascinated by our front room and spent time in there listening to my parent’s eclectic vinyl record collection and looking for photo albums for family resemblances. But I also felt it was kitsch and was embarrassed because my friend’s living rooms didn’t look like ours. As part of developing my anthology The Black Boy Pub & Other Stories, I did some oral history work with Caribbean elders in High Wycombe (UK) where I was born. The interviews took place in different living rooms, but they all looked the same. It was an epiphany. I realized the front room was part of me and therefore worth exploring creatively. The opportunity came when the Wycombe Local History & Chair Museum invited me to curate an exhibition but had no money. Necessity being the mother of invention, I borrowed my mum’s crochet and ornaments and my late Auntie Lorna’s upholstered three-piece suite, glass cabinet, radiogram and a picture of The Last Supper. This was the first iteration of The Front Room entitled, The Black Chair: An Installation and Exhibition Rediscovering the West Indian Front Room (1998-99).

Other iterations of The Front Room came before The West Indian Front Room: Memories and Impressions of Black British Homes at the Geffrye Museum 2005-06. As an interactive multi-media exhibition with a central front room installation, it was the most successful exhibition at the museum. This was because it had a cross-cultural appeal beyond the Black British experience in speaking to other migrant communities: Southeast Asian, Turkish, Greek Cypriot, Jewish, Irish migrant, as well as white working communities about everyday domestic lives ignored in British design and social history. These shared affinities reflect our transcultural interconnectedness, which resists the neo-colonial project of divide and rule. Building on this universal appeal, The Front Room is now a permanent 1970s period room at the Museum of the Home (formerly the Geffrye Museum).

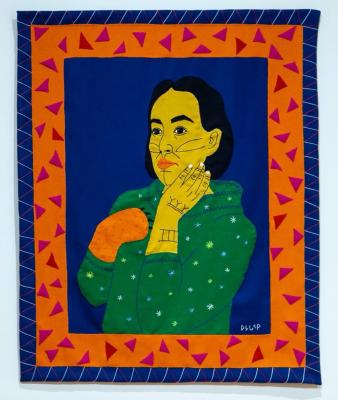

Through my interdisciplinary practice, I am interested in how identities, desires and impressions are performance in the front room, and therefore how visitors performatively experience the installation. As well as attracting migrant and working-class communities, who might not usually visit museums and galleries, iterations of The Front Room evoke/invoke memories of growing up of particular eras, and their associated domestic material culture that carry emotional, spiritual, social and cultural meaning. As part of Life Between Islands, co-curator David A Bailey, has told me that The Front Room has a similar appeal. I would envisage a similar response with The Front Room: Inna Toronto 6ix.

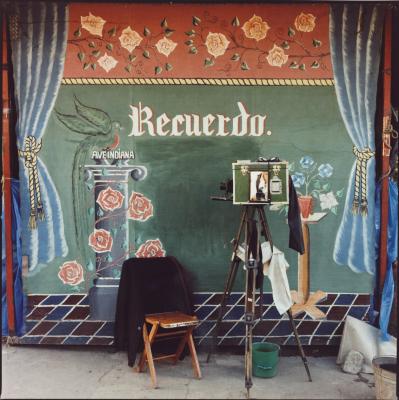

Michael McMillan, The Front Room: Inna Toronto/6ix, 2023. Mixed media site-specific installation © Michael McMillan. Photo: Sean Weaver © AGO.

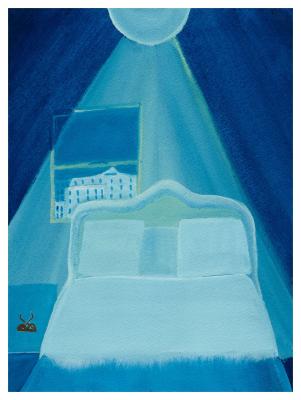

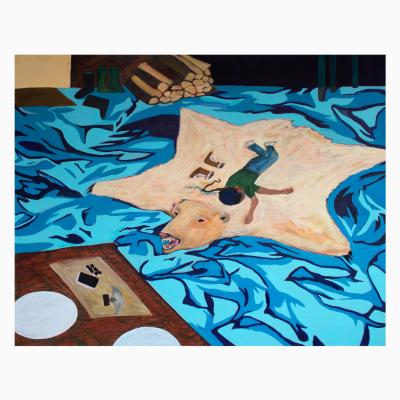

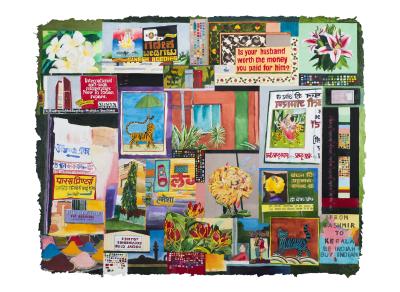

Foyer: The Front Room: Inna Toronto/6ix is based on a Caribbean home, situated in Toronto in the 80s. What are some of the specific elements of the room that best signify the city at that time and why?

McMillan: London was the metropole centre of the British empire, and Toronto was a satellite, where Caribbean migration begins there en masse from the late 1970s onwards. This movement is diasporic, as some Caribbean migrants coming to Toronto may have been resettling from the UK or New York in the USA, as well as also coming directly from the Caribbean.

The front room in Life Between Islands, belongs to Gloria, who stayed behind in the Caribbean as a child when her family emigrated to the UK as part of the Windrush generation in the early 1950s. Gloria mother, Carmen, trained as a nurse with the National Health Service, and Gloria becomes a nurse, in Scarborough, Ontario, where she marries and creates a family.

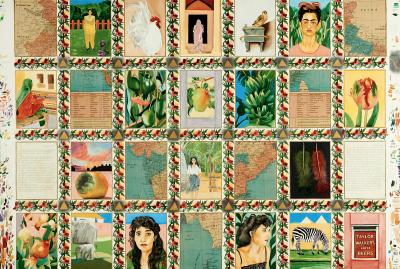

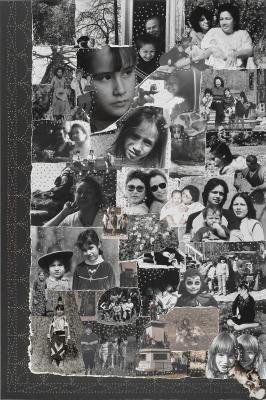

We encounter Gloria’s front room during the 1980s, and we experience the material culture of her family’s everyday lives. Though there is a loosening of that coloniality associated with earlier iterations of the front room, there are continuities shared across the diaspora: as expression of religious identities, here a Black version of The Last Supper picture and the presence of the bible; technological adaptation, such as listening and dancing to music, calypso, reggae, soul, RnB, jazz on vinyl records and tape cassettes, including a brochure from a The Jackson’s concert, and watching television, here VHS home movies. Her teenage children are of the emerging hip-hop generation, who if not playing video games, leave their hoodies and high-top trainers in the front room as if it were their bedroom. There are also memories of ‘back home’ with souvenir wall hangings, and an expression of Black consciousness through a picture of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, African sculptures and prints. Like Carmen, the front room is still a feminine domain for Gloria, that expresses her respectability as a mother and spouse resisting ongoing colonial racist tropes of the Black family as dysfunctional and pathological. Finally, there are framed photographic portraits of family and friends sourced from the Vintage Black Canada archive, including those of displaying Black female nurses, proud in their pressed uniforms.

Michael McMillan, The Front Room: Inna Toronto/6ix, 2023. Mixed media site-specific installation © Michael McMillan. Photo: Sean Weaver © AGO.

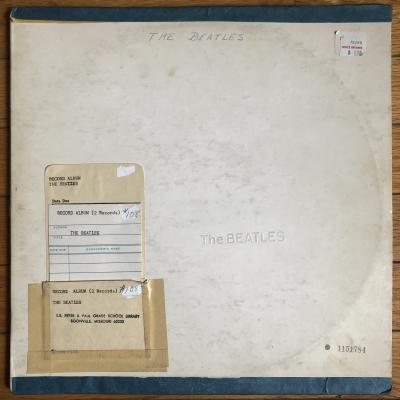

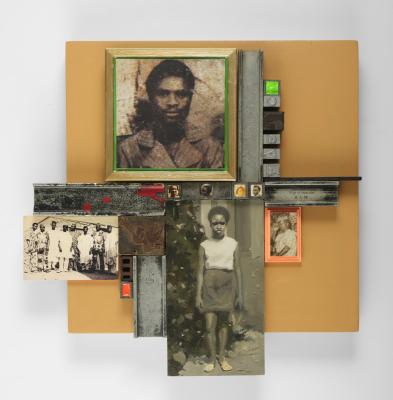

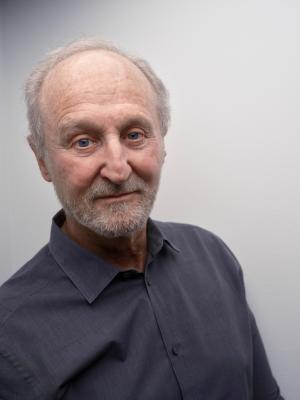

Apart from the UK and Canada, you’ve created regional iterations of The Front Room in South Africa, The Netherlands and France. What are some of the materials/qualities that have been present in every iteration? Can you share something you’ve learned (or come to understand better) about the global Black experience in the mid to late 20th century through studying front rooms?

I always attempt to recreate iterations of The Front Room from scratch, which enables research with local migrant communities, collecting local oral histories, towards sourcing local materials that reflect the domestic interiors of these people.

Through different iterations of The Front Room, I have observed shared expressions of being and becoming in the home as noted above: an engagement with sound technology development that Black people have been historically excluded from, yet they masters of through Black music; expressions of religious and spiritual identities, which resist colonial tropes that portray Black people has having none; souvenir wall-hangings and ornaments, framed photos that testify to ancestry, belonging, identity and subjectivity through the visual. Because patriarchy, the front room remains a space dressed by women, who are often judged on its maintenance.

Through researching different iterations of The Front Room across the diaspora, I have also learnt about similar yet different cultural politics. For instance, in London and Amsterdam, as the metropole centres of respective British and Dutch imperialism. And in terms of the urban vernacular, if Jamaican culture is the dominant street culture in London, and other centres of Black settlement in the UK, then Surinamese culture is of Amsterdam and Rotterdam. This is because Suriname, like Jamaica in the Caribbean, were significant colonies territories who resisted and revolted against Dutch and British slavery and colonialism.

Michael McMillan, The Front Room: Inna Toronto/6ix, 2023. Mixed media site-specific installation © Michael McMillan. Photo: Sean Weaver © AGO.

Do you have a bucket list of locations where you’d like to create front rooms in the future? If yes, could you share a couple of them, and tell us why specifically?

There is more to be learnt through iterations of The Front Room in the diaspora: elsewhere in the Caribbean, South America, Europe, including Africa and Asia. I am particularly interested in the United States, not simply because of Caribbean communities settled there, but also to make connection with African-American communities, who ostensibly do not engage with a sense of diaspora.

The kitchen is a more informally social space than the front room, and this has become a current interest through my installation I Miss My Mum’s Cookin’, which was first iterated in the Caribbean artist group show, Who More Sci-Fi Than Us, Who More Sci-Fi Than Us, KAdE Kunsthal, Amersfoort, The Netherlands 2012. Not a kitchen, but a homage to my mother, created from her cooking utensils that I collected she passed away. I inherit her food culture: spices, seasonings, preparation, cooking techniques, dishes and ways of eating.

I was asked to recreate it for the Brighton Fringe, 2023, to which was added signature recipes printed on tea cloths that I collected. With this iteration, I also facilitated a sensory workshop where participants, smelt, felt, tasted different spices, seasonings and food stuffs, and shared stories about how they were used and experienced.

As well as I Miss My Mum’s Cookin’, I have pulled threads from the material culture of The Front Room that informed other installation-based exhibitions: The Beauty Shop (2008), My Hair: Black hair culture, style & Politics (2013), Rockers, Soulheads & Lovers: Sound systems back in da Day (2015-16). As these works inform ongoing research that I would like to explore across the diaspora and beyond.

Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art, 1950s–Now is on view now until April 2024 on Level 5 of the AGO.