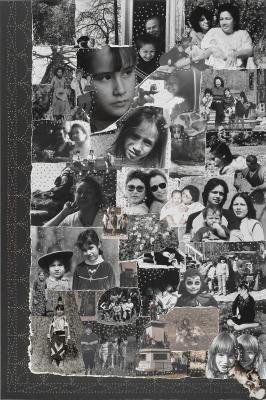

Alexa Kumiko Hatanaka’s washi futures

The Japanese-Canadian artist speaks about washi and the art of wearable sculpture

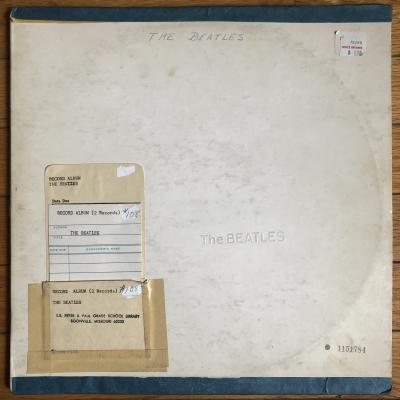

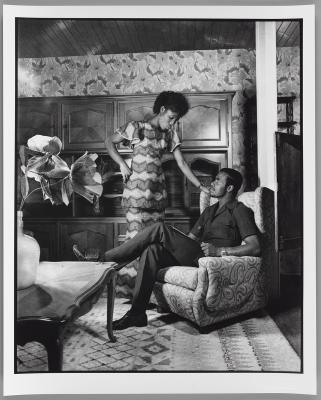

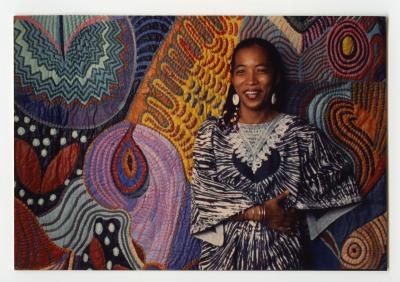

Hatanaka in her washi wearable art and flying her "Kochi Koinobori," Kochi, Japan. Photo by: Johnny Nghiem

Alexa Kumiko Hatanaka first encountered the sacred Japanese tradition of washi (Japanese paper) as a child when she was gifted several paper dolls from her grandmother. Fast forward a couple of decades, and the Japanese-Canadian artist has built a thriving and rigorous practice that features the art of washi manifested as wearable clothing (Kamiko). Hatanaka’s immersive study of this ancient discipline is exemplified by a three-month residency she completed earlier this year at Kashiki Seishi – a fourth generation washi mill located on Japan’s Niyodo river.

Currently on view at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre (JCCC), Unchanging and changing and changing is a solo exhibition by Hatanaka featuring wearable artworks made exclusively with washi from Kashiki Seishi. On Thursday October 12, 2023, the official opening of the exhibition and a performance installation of the same title are happening live at the JCCC. Fusing elements of live music, traditional Japanese dance and wearable paper garments from the exhibition, the performance will personify the core elements of Hatanaka’s art practice – all housed in a building she frequented as a child, taking dance lessons and attending community gatherings.

We spoke to Hatanaka about washi, the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre and her philosophy on wearable sculpture.

Foyer: When and how did you first become interested in kamiko and washi? How did you go about incorporating these ancient traditions into your practice?

Hatanaka: I was gifted several washi, Japanese paper, dolls that are dressed in kimono from my obachan (grandmother) as a child, but I hadn’t seen them again until recently – it made me realize washi, craft and the treasure of cultural inheritance has been embedded in my early imagination and play.

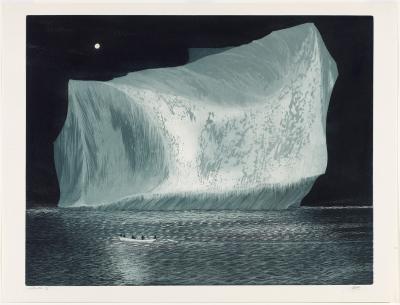

I started using washi in my art practice when I studied printmaking beginning in 2009 and have been using it for relief printmaking, which has a long history, ever since. I learned papermaking in 2011 and discovered that washi is an over 1000-year-old craft that can be very thin yet strong and malleable.

I began researching kamiko around 2018, and was mind blown by how durable and functional washi can be. It was even used to make firefighters gear! Washi clothing was worn even more commonly than fabric until it started fading out in the 1800s. Now it's almost non-existent. When people experience my work there is always that element of surprise at the material because our most common relation to paper is disposable, environmentally devastating, and a weak material.

Some of the shapes I sew are somewhat traditional or inspired by traditional farming gear and protection, but mostly they are contemporary and often intersecting with fashion.

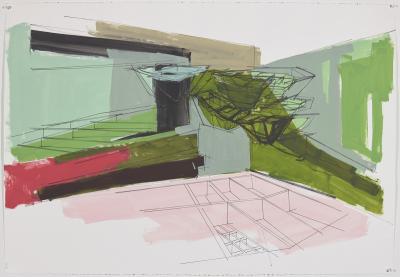

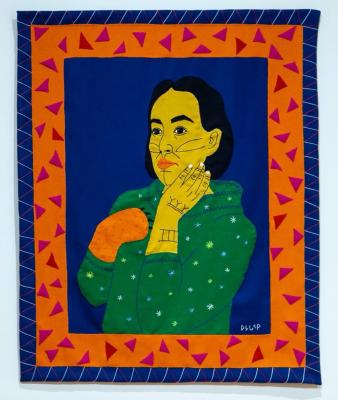

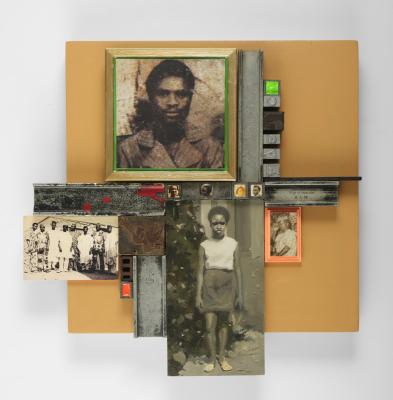

Hatanaka's studio at Kashiki Seishi, a washi mill in Japan of seventh generation washi makers. Photo by: Johnny Nghiem

Foyer: Can you describe your artistic philosophy and creative approach to wearable sculpture? Why is it a particularly special creative space for you?

Hatanaka: I have a deep foundation of community-engaged, social projects. Collaboratively finding ways to manifest tangible impact from art practice. Applied to washi, my motivation is to be part of sharing the significance of washi and its tireless makers, and envisioning even more possibilities for it into the future so that it may survive.

It has felt important to dissolve the boundaries between music, fashion, art, and functionality to reach more people and encourage other creative peoples’ engagement with the craft technology. I also want it to be clear that washi can be for everyone, it isn’t meant to be a niche thing or only to be preserved for Japan alone.

The wearables I have been making are both intentionally for specific performances or performers, and also for daily life, particularly joyful moments like dancing. In this way, the memory and expression of the wearer is embedded in the artwork, it’s an object full of life and story and connection. The process is also the artwork – the conversation, sharing, and FUN with friends and with artists I really appreciate.

Washi both requires a clean environment to be produced and it positively contributes to a healthy ecosystem, it can go back to earth as part of a natural cycle. Natural methods are reflective of the reality of life and capacity of the earth, and this is more crucial than ever – humans have already spent generations perfecting these harmonious ways of being, it’s important to pay attention to that.

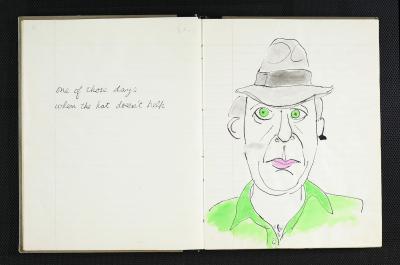

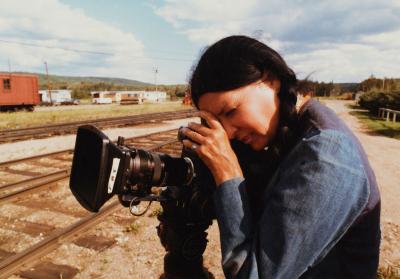

Mist Walker in Hatanaka's washi wearable art and flying "Neko Noren/ Flag" in Tokyo. Photo by: Johnny Nghiem

Foyer: Can you share some details with us about your artist residency experience at Kashiki Seishi? What were some of the technical processes you learned there? How much of the work in the exhibition was produced there?

Hatanaka: Kashiki Seishi is an inspiring washi mill run by seventh generation washi makers. After connecting with Ayumi Hamada that created and runs the visitor farming program and artist residency, we realized that it is their washi that I use the most in my practice! I used washi I made there, but the majority of the washi I used is produced by Kashiki Seishi. Also, the documentary and photos in my exhibition by Johnny Nghiem, capturing the mill, my process and the wearing of my artwork in Japan were created there.

I went fishing and I non-toxically printed the fish we caught onto washi which is a technique called Gyotaku. I use this a lot in my practice to then starch and sew into my work.

One highlight was making washi in the Niyodo river with the master Tatsuyuki Kitaoka which was such a gorgeous experience really exemplifying how integral that particular pristine water is to the washi and people of that region.

I helped harvest kozo, prune, sort and cut, and communally peel steamed kozo so that the inner bark can then be beaten into pulp, picked of any specs of outer bark and then made into paper. I learned that washi isn’t the stand-alone object so much as it is an expression of the environment, the people, the function of family and community, and the fierce care for ancestors' contributions and passing on highly purposeful traditions for future generations…it holds all of the seasons and relations over 1000 years. Washi in general also holds inherited techniques from Korea and China that traveled via Buddhist monks so the history and knowledge goes back even further.

Foyer: The exhibition is on view at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre. Why was it important for this to be the home of the exhibition? What is your personal connection to the space?

Hatanaka: I am Japanese Canadian and I spent a lot of time at the JCCC growing up, including taking part in Japanese dance lessons, and performances. The ritual of being dressed by elders in these special garments and the communal folk dances at festivals really stuck with me.

I was happy to be invited by the JCCC to envision a project there and the opportunity to create a dance performance came to fruition. I additionally have been connecting to the Japanese Canadian creative community which has been so nourishing and so this performance and work really couldn’t be anywhere else.

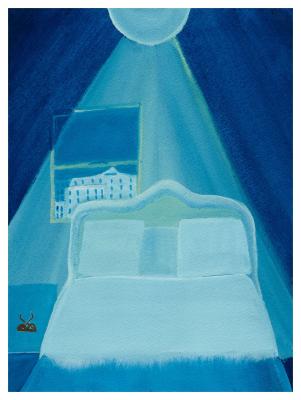

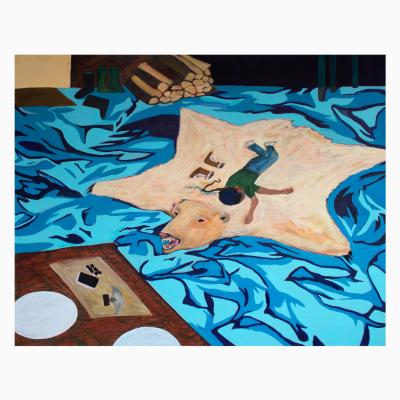

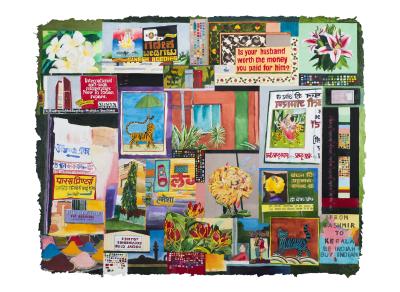

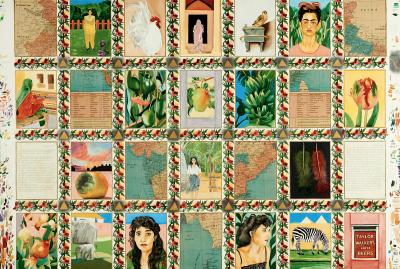

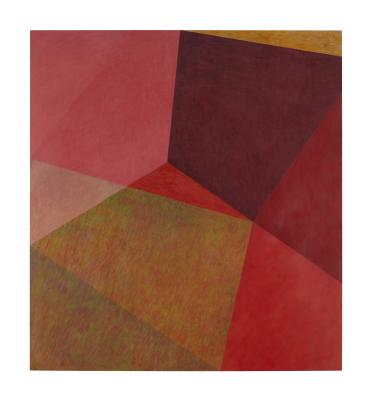

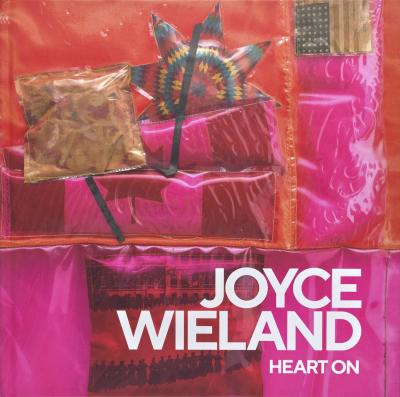

Works "For Nihon Buyo (Rain Defense)" and "For Nihon Buyo (Juban)," Washi , printmaking, natural dye, ink, 2023. Photo by Darren Rigo

Foyer: The exhibition’s official opening event features a live performance that brings together elements of music, dance, and works from the exhibition. Without too many spoilers, can you share some details about the performance piece and the inspiration behind it?

Hatanaka: Yes! All the performers will be in washi wearable artworks that I made for them.

Benja and Peach Luffe, very special local musicians, will play together and have previously worn my work – I had to make my first pants ever and it was a fun challenge.

For the collaborative performance of the same name as the exhibition, Unchanging and changing and changing, I had been reflecting on the folk dances I mentioned starting about three years ago while I simultaneously started moving through a very big life change, processing a lot of grief from things over many years, and struggled to get a handle on my chronic health condition. The exhibition and performance has a lot to do with this, emerging from lots of isolation to full expression, connection and cultivating joy. That’s why the opening ends with a dance party with amazing DJs!

Taiko drummers Jody Chan and Wy Joung Kou composed something so moving and with arm movement that is dance choreography unto itself.

Nihon-Buyo dancer Katherine Yamashita had the conceptually perfect idea to dance with her daughter Danielle. One special serendipity is that I danced with Danielle as a child at the JCCC! They are some of the few people with deep lived knowledge of the dance and have a similar interest as I do in honouring the integrity of a historical practice while approaching it in a personal way to evolve its relevance into the future.

Unchanging and changing and changing the official opening and live performance is happening October 12, 2023 at the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre. Register for free here.