Eric Newman reflects on his father Arnold Newman

He shares childhood memories, experiences on set and his father’s lasting influence

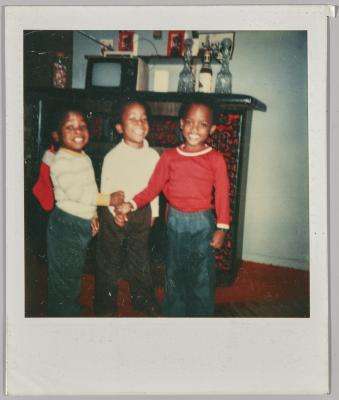

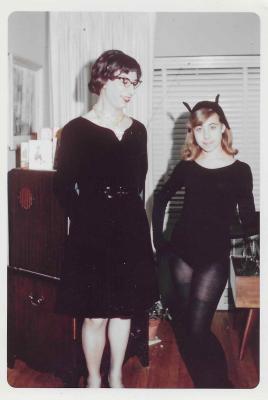

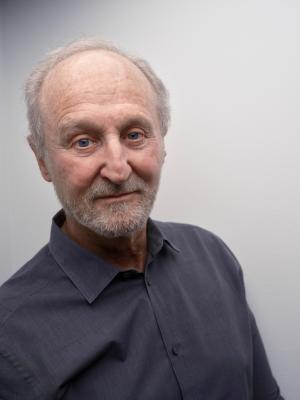

Family snapshot of Arnold, Mark and Eric Newman in 1983. Photo Courtesy of Eric Newman

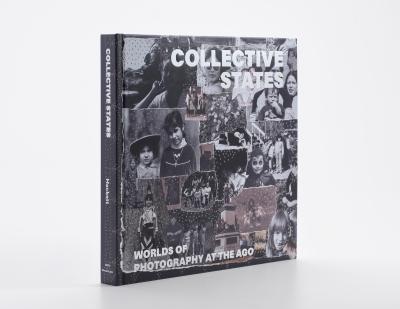

Acclaimed photographer Arnold Newman’s famed portraits are best known for expressing biography, creative vision and professional expertise. A collection showing the breadth of his photographic practice, particularly those commissioned for magazines, has been the subject of a major solo exhibition at the AGO. On view until January 21, Building Icons: Arnold Newman’s Magazine World, 1938-2000 highlights Newman’s style and influence on 20th-century photography.

But beyond his work as an photographer, who was Arnold Newman as a person, a husband and father? Looking to get a more personal perspective of Arnold Newman himself, we connected with one of his sons, Eric Newman. He spoke to Foyer about the importance of family, memorable moments working alongside his father, what he learned from him and much more.

Foyer: Your father worked closely with your mother, Augusta, throughout his photography career. How would you describe her influence on his practice? What role did she play?

Eric Newman: My mother was the office manager for the studio and assisted with doing a lot of the research for stories for his magazine shoots. She helped to plan out his work trips. I think a much more important influence was the love that they had for each other. The most important thing in my father's life was his wife and his family. That was true throughout his life, and he would be the first person to tell you that. In a sense, it was almost embarrassing. If he met some important person, he would often want to tell them about how great my brother and I were. He was very proud of us. His love for his family was the most important thing in his life.

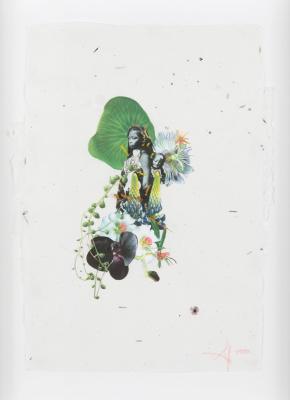

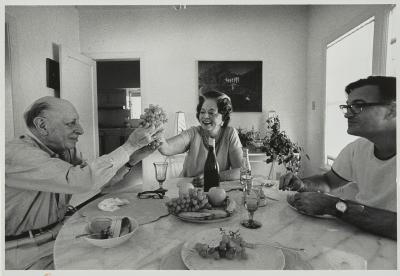

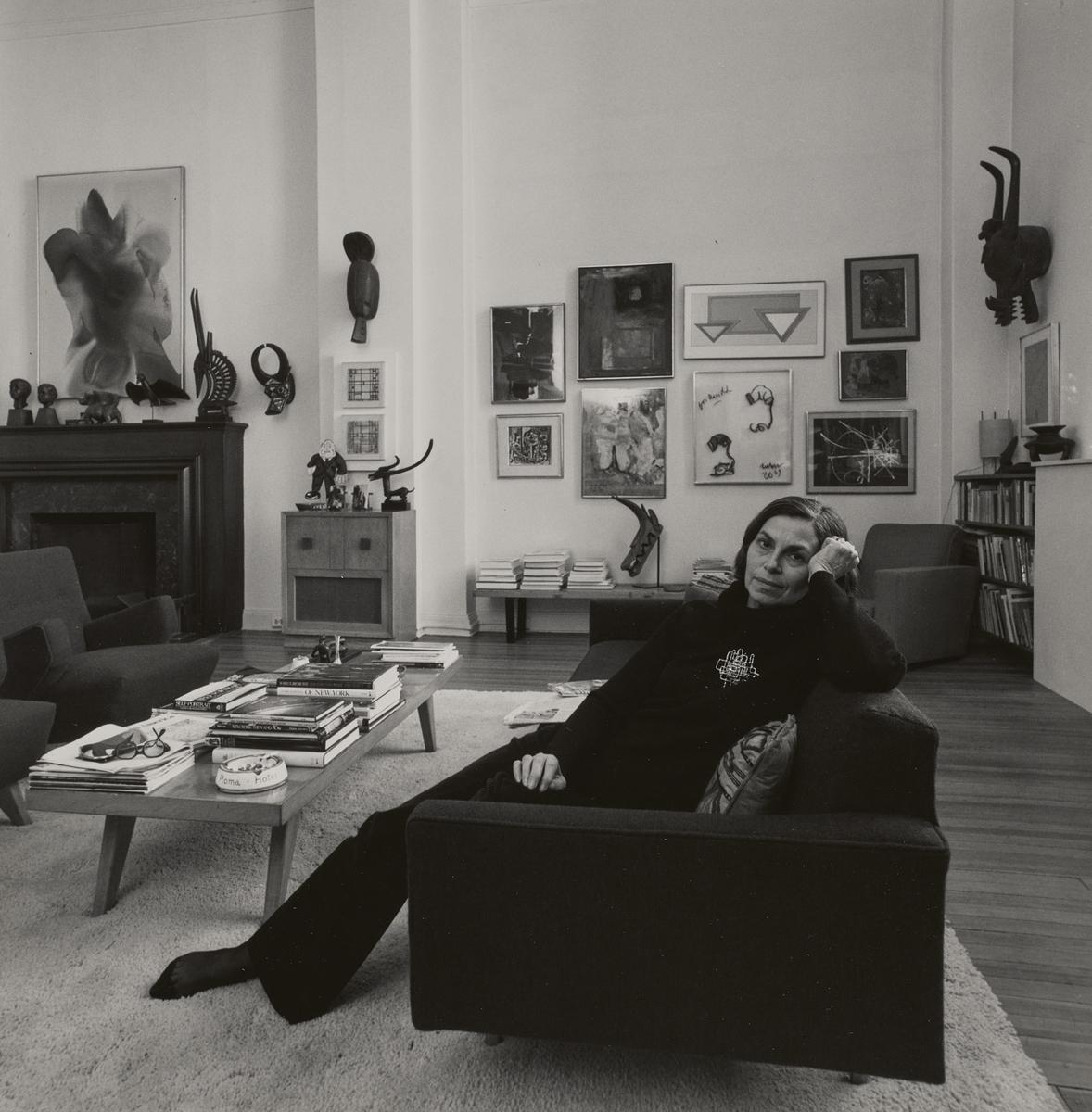

Arnold Newman. Augusta Newman at Home, New York, New York, 1977. Gelatin silver print, 35.6 × 27.9 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Anonymous Gift, 2012. © Arnold Newman Properties/Getty Images (2023). 2015/2416

Foyer: I understand you were also involved in his shoots sometimes, what was your experience?

Eric Newman: I think he probably used me as a model many times early in my life that I wasn't aware of. It wasn't until I was an adult, that he showed me a picture where I was featured on the cover of Life magazine. I was four years old at the time and I obviously didn't remember it. But I do remember that when he was going to plan out a photograph, he would get a person to stand in for the sitter to check the lighting and composition and so forth. So, I did that a lot together with his assistants.

Foyer: Do you have any memorable moments assisting or as a sitter in his works?

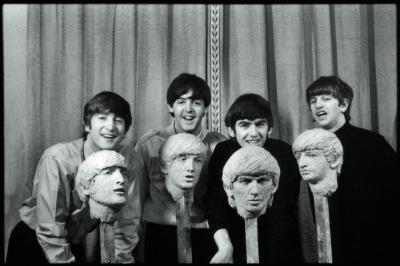

Eric Newman: There were a few memorable moments. One I really remembered was when he took a portrait of I.M. Pei in his architectural office in New York. I acted as his assistant there, lugging all the camera cases, moving lights and so on. A second time was when he was commissioned to do a book on Michelangelo's Pietà. He had the opportunity to photograph the sculpture when it came to New York during the 1964 World's Fair, in the Vatican Pavilion. He was given an opportunity to photograph the sculpture overnight from when the Vatican Pavilion closed one evening to when it opened the next morning. So, he spent the whole night photographing the sculpture and I was there. I was only 14 and I don't think I acted as much as an assistant as simply an observer, but that was memorable.

Another story was when he photographed Igor Stravinsky, first in 1946 and then again in 1966, when Stravinsky was preparing for the premiere of one of his last pieces, Requiem Canticles. I went to that premiere at Princeton and they did a recording of the piece. An initial pressing of the record was made for Stravinsky to review. He received this record but they didn’t have a record player in his hotel room. I had to race from the hotel, where I was visiting Stravinsky with my father, back to my home and bring my portable cheap record player back to the hotel. That’s how he listened to the first version of the record of that piece – on my cheap record player.

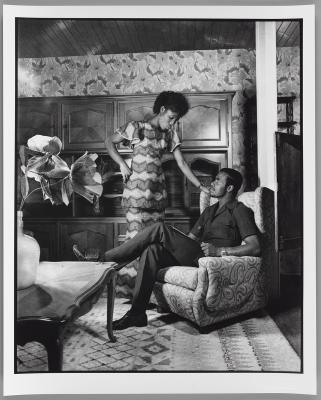

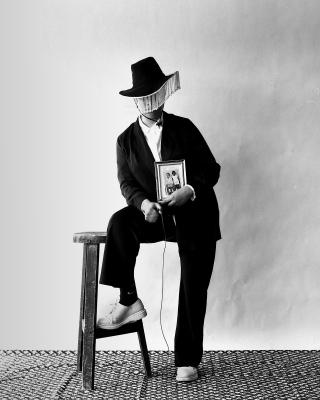

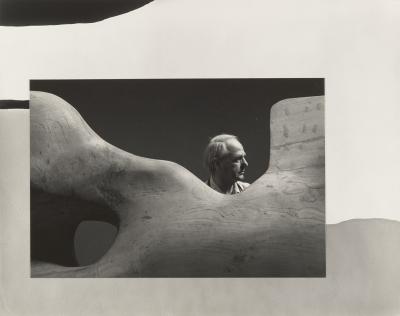

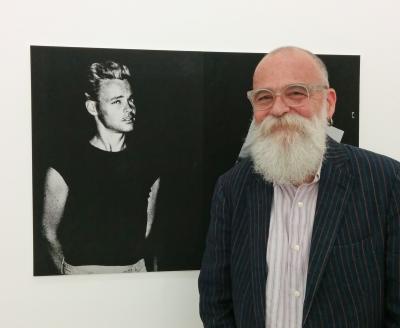

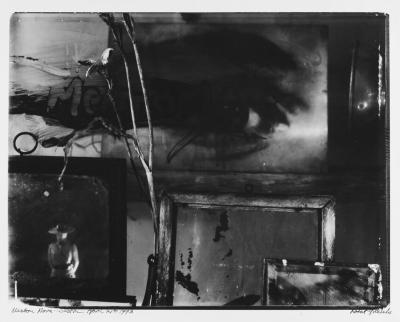

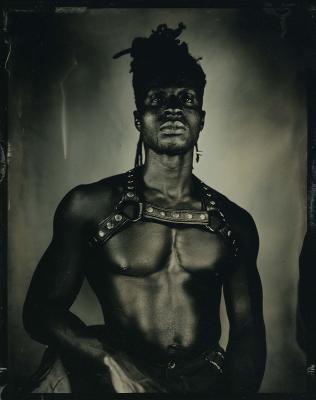

Arnold Newman. Self Portrait, 1979. Gelatin silver print, 35.6 x 27.9 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Anonymous Gift, 2012. © Arnold Newman Properties/Getty Images (2023). 2015/2569. Commissioned by New York Magazine.

Foyer: How would you describe his “off-duty” or “everyday” photography? In what ways was it similar or different from his professional work?

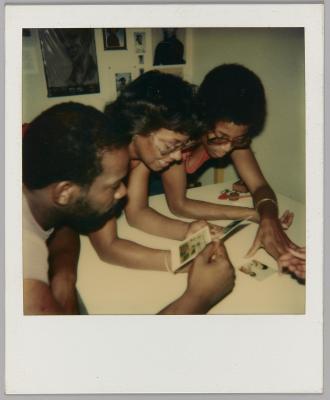

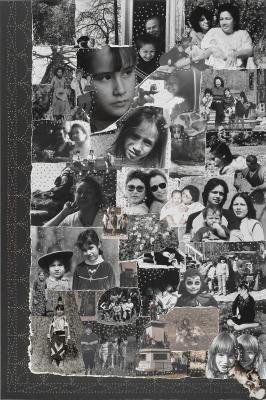

Eric Newman: It was very different. They were really just snapshots but I guess there was a range. He would take portraits of his family and those were (kind of) arranged. So, there was both. For the snapshots, they were truly just snapshots with little to no planning of the photograph itself. Another big difference, which his family and friends who wanted to get copies of these pictures would know about and what he was famous for, was that he would sometimes take months or even years to print the pictures before people received them. And he never, ever, took the effort to organize them. We never had family albums, not even a hint of one.

My wife found out about this one day when she wanted to see a picture of me when I was younger when we were visiting him in New York. All these candid snapshots were just dumped into 8 by 10 print paper boxes. There were maybe 30 to 40 boxes with no labels. Somewhere in that batch was a picture of me. So, we piled the boxes up on the dining room table, two or three deep, and opened each, one at a time. We started going through them and of course, he began telling stories about when he took a portrait of this famous person or that. Several hours later, he had only gotten through several boxes, and we never saw a picture of me. But that’s how he organized family snapshots – they weren’t organized at all. It wasn’t until many years after my father died that my brother and I went through and digitally scanned many of them and placed them in some kind of order

Foyer: Was there a pivotal moment in your life when you began to understand your father’s profession and his impact?

Eric Newman: I must’ve been in my early teens, but it was when I saw his well-known portrait of the painter Willem de Kooning. The picture shows de Kooning peeking through a slit in a drop cloth. You can only see a part of his face in the photograph. So, I asked my father, how is this a portrait where you can’t really see the person? He explained to me that despite the way his face was positioned, the portrait is showing the essence of de Kooning and his work. He explained the intentions behind the portrait. So that is one point at which I learned a lot about what his photographs were like and why they were important.

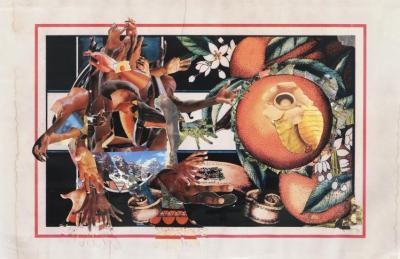

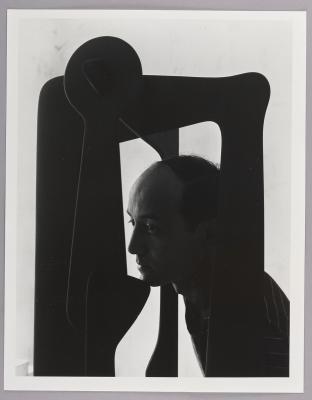

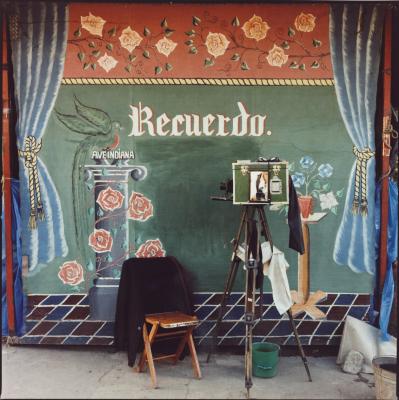

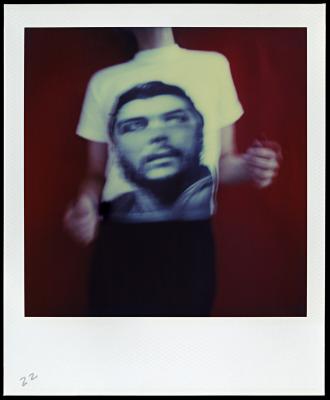

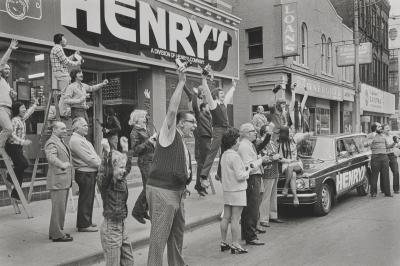

Arnold Newman. [Arnold Newman working on “What Do U.S. Museums Buy?”], 1950. Gelatin silver print, Overall: 25.4 × 20.3 cm. Art Gallery of Ontario. Anonymous Gift, 2012. © Arnold Newman Properties/Getty Images (2023). 2015/693.

Foyer: Did Newman share any advice with you about work ethic? Did his art practice somehow influence the way you work, even as a scientist?

Eric Newman: Very definitely. He had a very, very strong work ethic. And I think that I do, too. I learned a lot about how to work from him. There’s one small habit that always reminds me of him. He had a small part of his studio where he stored tools which he used to build sets for advertising photographs. And whenever I used these tools or his darkroom, he insisted that I had to clean up right away. It was very important to completely clean up after your work. That made a big impression on me, and I feel the same way about that myself. I always tell my students to do that as well. But in general, I really look up to him and try to model how I work and my attitude towards work from him.

Foyer: What was your experience at the AGO exhibition?

Eric Newman: I thought it was a fantastic exhibit. First, I was extremely impressed by how much the curators knew about my father. I think they went well beyond and knew so much more – everything from his personal life to his work life, than I ever knew. I found that very impressive. I also loved the way they put together the exhibition. When Sophie first told me that the exhibit was going to be based around his magazine work, I was a little puzzled. It wasn't until I saw the exhibition that I realized, which I hadn’t known, that almost all his famous pictures were taken as part of magazine stories. So, I've learned a tremendous amount about how he worked from the exhibit. I was extremely surprised to see picture after picture that I grew up with that I hadn't realized was done for one magazine or another. I think it was a fantastic exhibit, and I learned a lot.

Foyer: What's your favourite portrait?

Eric Newman: I’d have say for a picture, it was a snapshot he took when my family was in the woods outside of Boston. My children were two and four years old at the time. We walked ahead, and he just took a snapshot with a point-and-shoot camera of us. It’s a very good photograph. And because it's my family, I guess that's my favourite picture. I have it hanging both in my home and in my office at work.

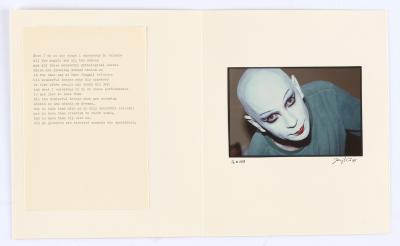

© Arnold Newman Properties / Getty Images

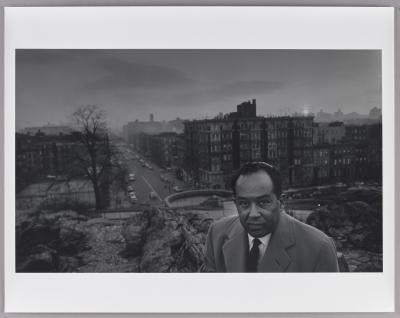

But I do have many favourite portraits by my father. My wife and I have maybe 15 of our favourites hanging in our dining room. It is sort of a mini exhibit of his pictures, and they include photographs of Martha Graham, Ansel Adams, Joan Miró, I.M. Pei, and, of course, Stravinsky. My father had a practise of after he took a portrait, he would go back to the sitter and have them sign the portrait to him. He often had them sign additional copies for me and my brother. So, I have a Stravinsky portrait signed by Stravinsky, that says “To Eric.” I also have signed photographs of Marc Chagall and Jacob Lawrence. He did that a lot. In fact, many of the photographs signed by the sitters were gifted to the AGO. You now have the largest collection of Arnold Newman portraits that are signed by the sitters.

Building Icons: Arnold Newman’s Magazine World, 1938-2000 is on view now until January 21 at the AGO on Level 2 in Sam and Ayala Zacks Pavilion (gallery 245). The exhibition is curated by Sophie Hackett, AGO Curator of Photography, with photo scholar and independent curator Tal-Or Ben-Choreen.

![Unknown photographer, Chillin on the beach, Santa Monica [Couple on beach blanket]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_small/public/2023-04/RSZ%20WMM.jpg?itok=nUdDiiKr)