A Great Day in Toronto Hip Hop with Patrick Nichols

The pioneering photographer speaks on documenting Toronto hip hop and The Culture's grand finale

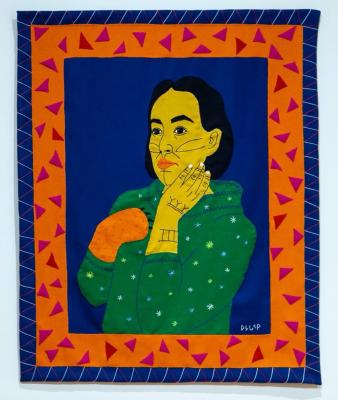

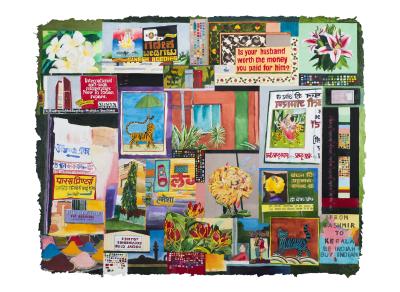

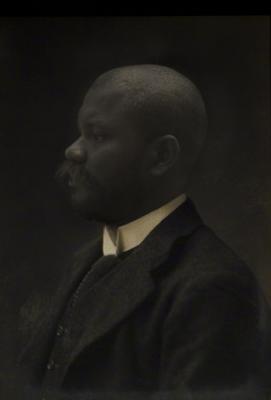

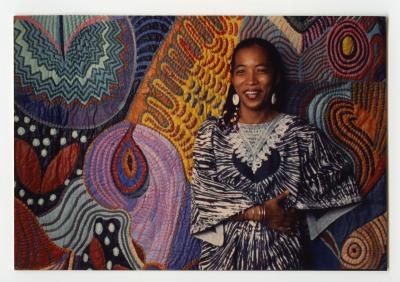

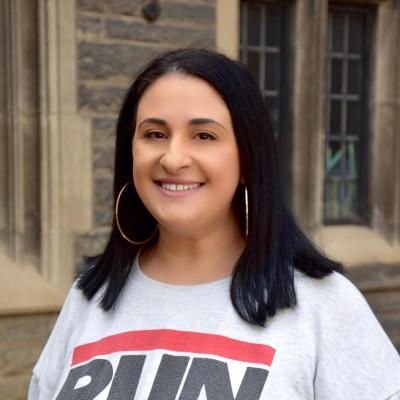

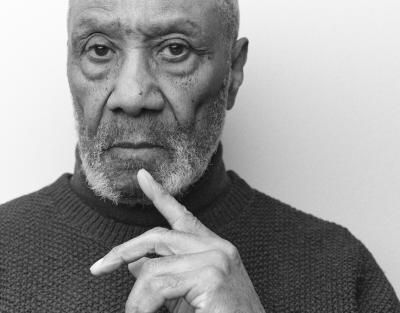

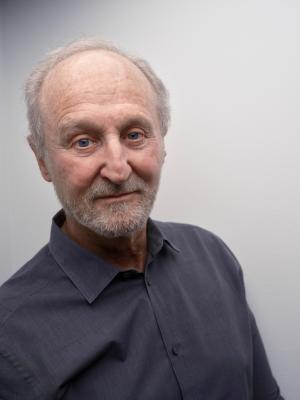

Portrait of artist Patrick Nichols. Photo: Craig Boyko © AGO

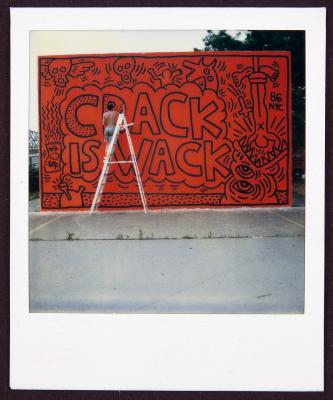

In 1958, music photographer Art Kane brought together 57 prominent jazz musicians on the stoop of a Harlem brownstone to create one of the most important photographs in jazz history. That year, A Great Day in Harlem was published in Esquire magazine, earning Kane numerous accolades for his work. It was so influential that in 1998, XXL Magazine commissioned a 40th-anniversary recreation of the seminal group portrait— this time focusing on hip hop. Shot by legendary African American photographer Gordon Parks, A Great Day in Hip Hop (1998) featured over 200 of the genre’s biggest names, from Rakim to E-40, and was published as the centrefold of XXL’s December 1998 issue.

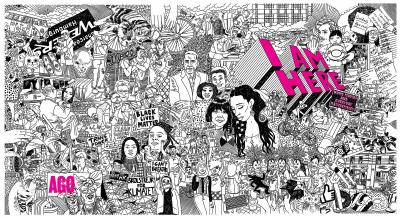

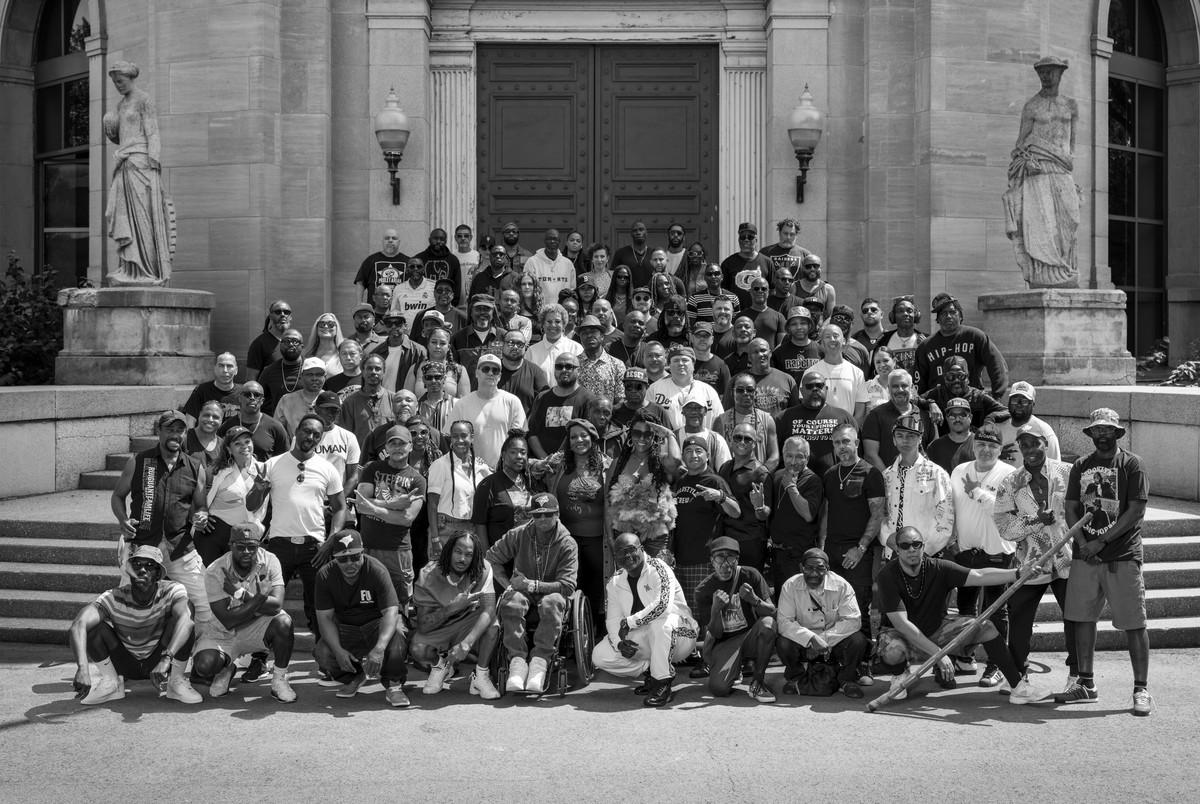

In conjunction with the Toronto edition of the landmark exhibition The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century, the AGO commissioned Canadian hip hop photographer Patrick Nichols to be the next torchbearer of the Great Day tradition. On August 14, 2024, Nichols gathered 103 key figures from three decades of Toronto hip hop for a massive group portrait on the steps of the Toronto heritage building, The Liberty Grand.

Described by Nichols as “a way to give back,” A Great Day in Toronto Hip Hop features a diverse group of MCs, DJs, break dancers, graffiti writers, promoters, designers and media personalities— most of whom he considers personal friends. Among them are the founder of Canada’s first-ever hip hop radio show, Ron Nelson; gold record-selling artists Choclair and Saukretes; and owner of the iconic vinyl shop, Play De Record, Eugene Tam. This monumental portrait is the exhibition’s grand finale, prompting visitors to witness and acknowledge the forebears of the Toronto hip hop community before they exit.

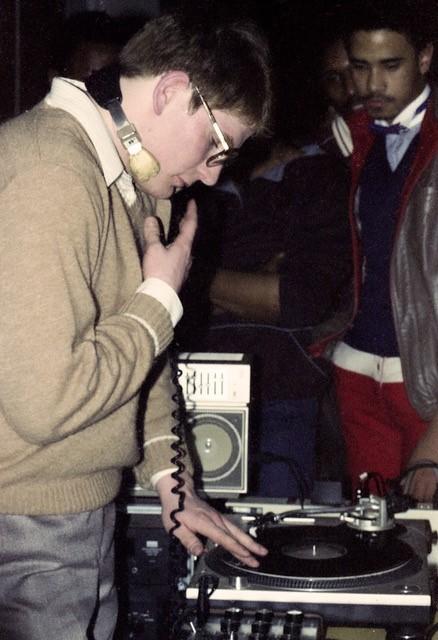

Born in Kingston, Jamaica, in 1965, Nichols moved to Canada as a child and spent his adolescence in Toronto and Chicago. At 19, he began studying photography at Humber College and later became the protégé of American photographer Dave Jardano. Around the same time, Nichols and his close friend Julian Arthur purchased turntables, hoping to DJ hip hop parties in Scarborough with the foundational Toronto music collective, Sunshine Soundcrew. Although he would eventually give up DJing to pursue photography full-time, Nichols’s place in the hip hop community gave him direct access to the artists, events and personalities at the forefront of the scene. After catching the attention of local artist manager and label owner Ivan Berry in 1991, Nichols became the official photographer for the European tour of The Dream Warriors, Gangstarr and Michie Mee. Since then, he has built a celebrated career, working in multiple spheres of photography in Canada and abroad.

We spoke with Patrick Nichols about his journey with photography in the 1980s and 90s, his experience shooting A Great Day in Toronto Hip Hop, and his thoughts about the exponential growth of hip hop culture over the years.

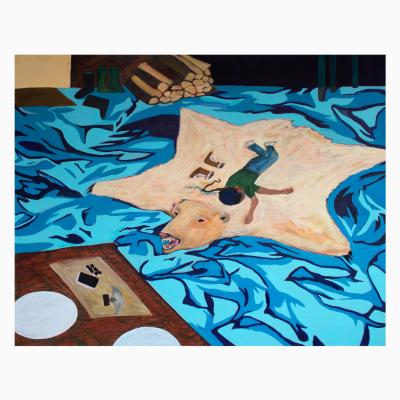

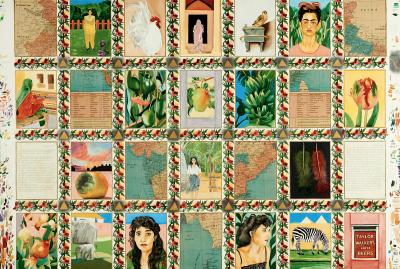

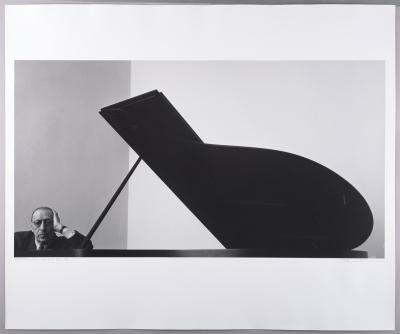

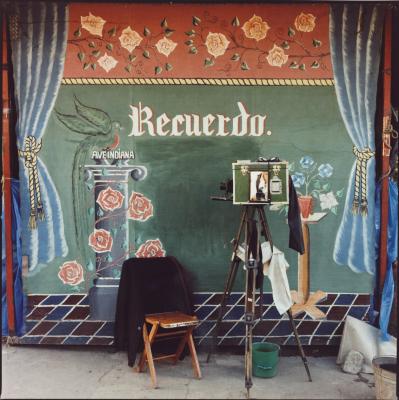

Patrick Nichols. A Great Day in Toronto Hip Hop, 2024. Inkjet print, Overall: 147.3 × 223.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist. © Patrick Nichols

Foyer: A Great Day in Harlem is a legendary photograph, and A Great Day in Hip Hop has become legendary as well. What do these two photographs mean to you and how did it feel to shoot Toronto’s edition?

Nichols: I was quite honoured to do this. I researched Art Kane and learned that he was actually a designer and a graphic artist, which is exactly what I wanted to do before I got into photography. Growing up in Jamaica, I would hear the famous “pop pop fizz fizz” Alka-Seltzer commercial and see how much it resonated with people. I wanted to create things with resonance. That’s what Kane did with the 1958 photograph, and it became legendary. Kane documenting these jazz musicians was a big honour for them because they didn't always necessarily get put in print.

Going back and forth between Toronto and Chicago as a teen, I always knew about Gordon Parks. He was a photographer for LIFE Magazine, which was one of the goals I had as a young photographer. In ‘98, XXL wanted a big name to take the photograph, so they got Parks. Although Parks is a legend as a photographer and it’s an important moment in hip hop history, I am curious as to why the decision was made to shoot with shadows cutting off the front row.

My relationship to this portrait began in 2016 when I had the idea to photograph everyone that I already knew in Toronto since I’ve had the privilege of shooting so much of the birth and renaissance of Toronto hip hop. The original idea started as a family tree, where I would create a group portrait including many people I’ve photographed - and some that I wanted to but never had the chance to. Eight years later when I got the opportunity to complete the portrait through the AGO, it made sense.

[Taking the photograph] was a daunting task. I called almost everybody that I knew to come and be in the portrait. I worked with Toronto hip hop historian from York University Francesca D’Amico-Cuthbert to gather everyone together. She’s currently working on recording and documenting the history of Toronto hip hop, so she was quite happy to meet so many people she’s been studying, all of whom happen to be friends of mine. I picked up the phone and called almost every person that came out for the portrait and knowing that the relationships I'd built since 1988 made it all possible felt great. It was a way for me to give back.

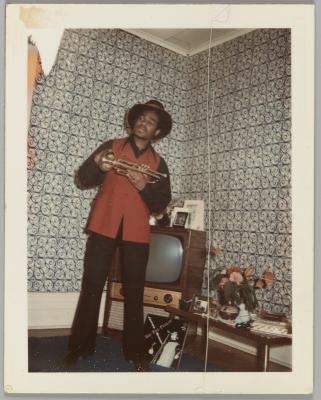

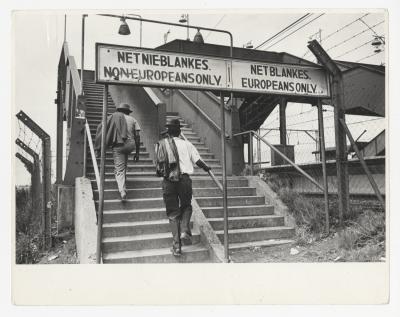

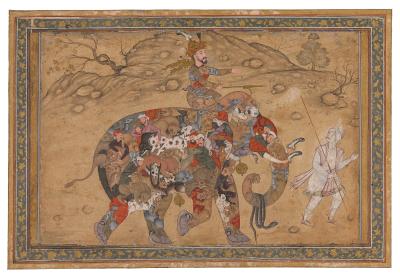

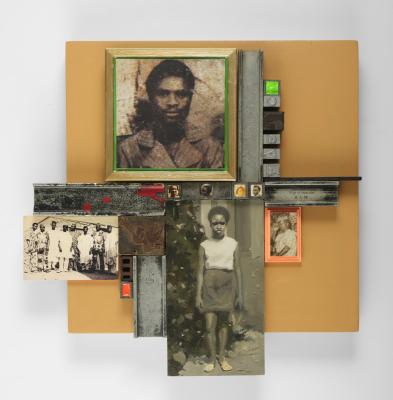

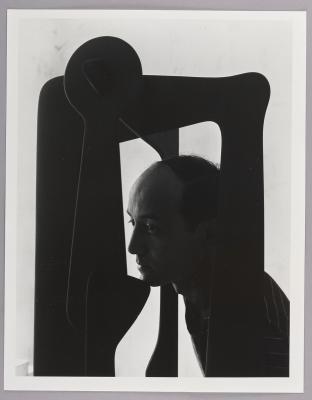

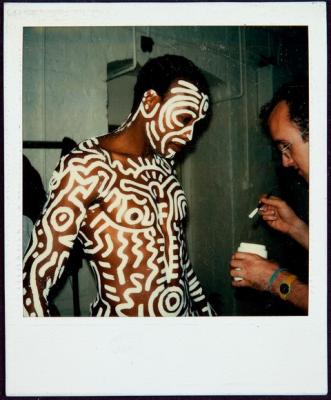

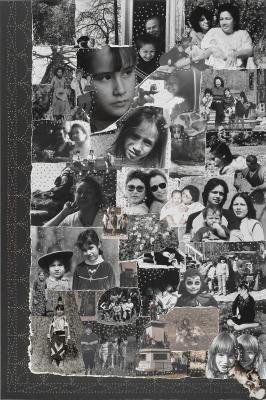

Patrick Nichols. Michie Mee and Guru in Europe, 1991. Courtesy of the artist © Patrick Nichols

You've been one of the foremost documenters of hip hop culture in Toronto for several decades. Can you share your inception story as a photographer, and talk about how your career blossomed in the 80s and 90s?

When I was 16, I got a job at McDonalds in Scarborough and worked there until I was 19. That job helped shape me and taught me that if I can work hard for myself and that I have what it takes to be self-employed. Then, I went to Humber College for photography. I did very well there for a few semesters, but I found the program under stimulating and not worth the money, so I left in search of ways to become a better photographer. I was then mentored by the American photographer Dave Jardano, who taught me about lighting, composition, and helped me to develop a sense of taste.

At the time in the late 80s, hip hop was beginning to become a thing in Toronto. A lot of Jamaicans had immigrated to either Toronto, New York or London and were building hip hop and reggae scenes in those places. I was DJing parties around the city, but I was primarily a photographer. Since I was already on the Toronto hip hop scene and knew so many artists and people of influence, it gave me unlimited access to interesting photography subjects. This was great practice for me, and useful for them for promotional reasons.

I ended up creating some photographs for a popular Toronto barber shop called Cut Creator, which got a lot of attention around the city. That’s how I met music manager and label owner Ivan Berry, who was managing both the Dream Warriors and Michie Mee at the time. In 1991, he brought me oversees to photograph their European tour, alongside Gangstarr [acclaimed New York hip hop duo]. I got very close to Guru (1961 - 2010) [of Gangstarr], who asked me to move to New York and join the group as their photographer. I declined - which I have no regrets about - because at the time I thought Scarborough was the centre of the universe and I had no intention of leaving. While in Europe I saw how massive a following Dream Warriors and Gangstarr had become and I knew hip hop was going to become pop eventually. I took so many important historical photographs during that period I decided to put together a book.

Ivan Berry managed so many influential Toronto hip hop and reggae artists - Krush and Skad, Michie Mee, Carla Marshal, Chase and Power. Then Chase went on to manage Kardinal, Saukretes and Jully Black. From there it just kept growing. I was basically at the epicentre of it all, trying to use photography to help build a visual world to support it.

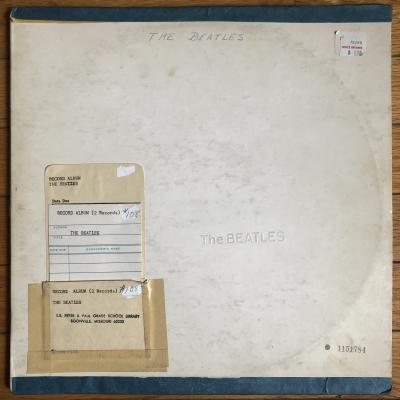

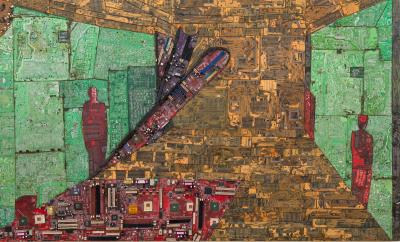

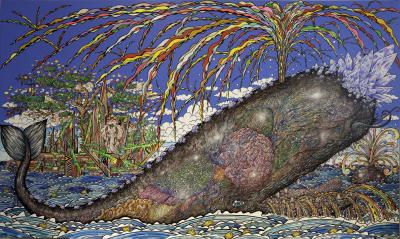

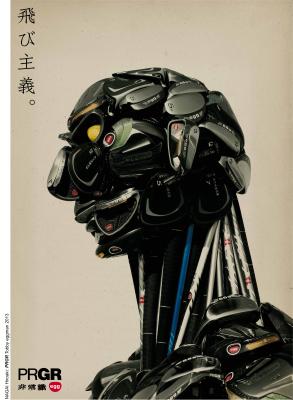

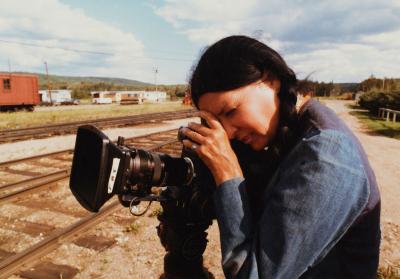

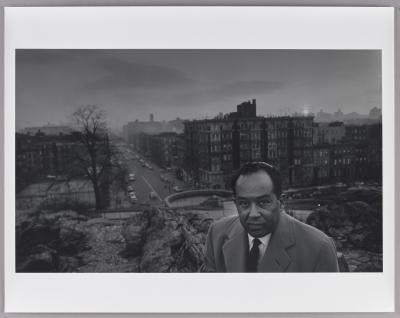

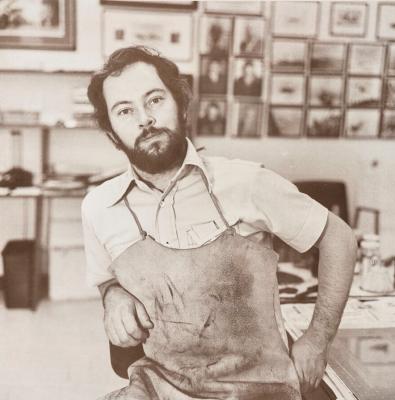

Patrick Nichols. K Force and Brother Different, 1982. Courtesy of the artist © Patrick Nichols

Reflecting on your career, especially your time documenting Toronto hip hop culture, are there any historically significant moments you witnessed that you could share with us?

The first thing that comes to mind are the massive block parties that Sunshine Soundcrew used to throw in the 80s. Everybody in Toronto would be there. That’s what really started the hip hop scene. Myself, Julian Arthur and Toronto rapper K Force would practice mixing daily, and Force would freestyle for over 40 minutes every time. It was amazing. Immediately, I suggested we start a crew and make some records instead of just doing parties, but Force refused and said he was too shy and that he was just fooling around. One day not too long after that I walked into a Sunshine party and they had our turntables and my records and K Force was on the mic rapping and rocking the party. I got so fed up with trying to organize the crew that I decided to sell my turntable and buy a camera, and from that moment I was a full-time photographer. After that, K Force introduced Michie Mee to Ivan Berry and that’s how the legendary Toronto record label Beat Factory got started. Julian Arthur went on to start another important Toronto hip hop label, Groove A Lot Records.

Portrait of artist Patrick Nichols. Photo: Craig Boyko © AGO

As someone who witnessed the inception of hip hop, what are your thoughts about how massive of a cultural force it has become?

I'm just sad I couldn't make more money out of it because I saw it coming. I wanted to write a book called The Globalization of Hip Hop in 1991, after I travelled around Europe and saw hip hop’s effect on the world. I knew hip hop was the centre of the universe. It involves fashion, music and style, so to see how big it’s become, I’m not surprised.

I’m saddened by what hip hop has lost: its depth of meaning. Hip hop started as the voice of disenfranchised communities who have been marginalized in society, and it’s no longer about that. If history teaches us anything it’s we’re doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past. Maybe hip hop as we know it now will die and then go back to its roots. More primal, conversational, uplifting, and educational. It seems like we’ve gravitated more to the lesser parts of ourselves, and people are thinking more about the money than the art.

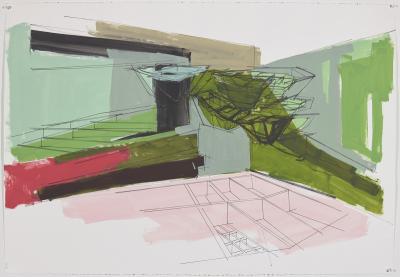

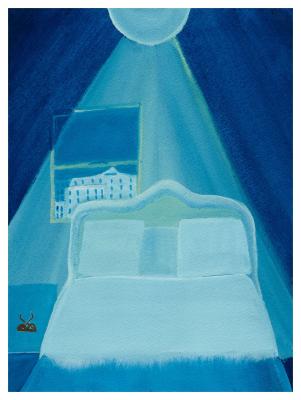

The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century is currently on view on Level 5 of the AGO. The exhibition is co-curated by Asma Naeem, the Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA)’s Dorothy Wagner Wallis Director; Gamynne Guillotte, the BMA’s Chief Education Officer; Hannah Klemm, Saint Louis Art Museum (SLAM)’s Associate Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art; and Andréa Purnell, SLAM’s Audience Development Manager. The AGO presentation is organized by Julie Crooks, Curator, Arts of Global Africa and the Diaspora, AGO.