All about chintz

ROM curator Sarah Fee discusses the floral-adorned textile as seen in Cassatt-McNicoll

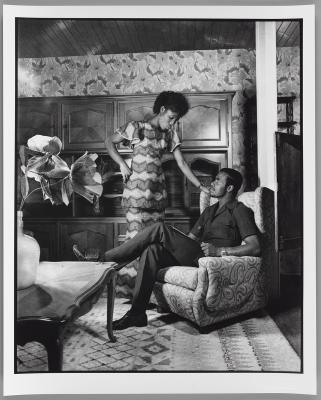

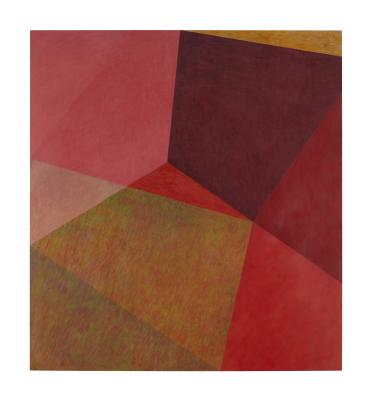

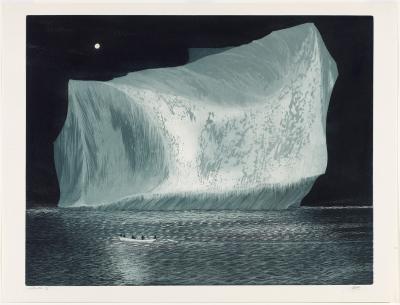

Helen Galloway McNicoll, The Victorian Dress, 1914. Oil on canvas, 107.1 × 91.7 cm. Art Gallery of Hamilton; Gift of A. Sidney Dawes, M.C., 1958. Photo: AGO.

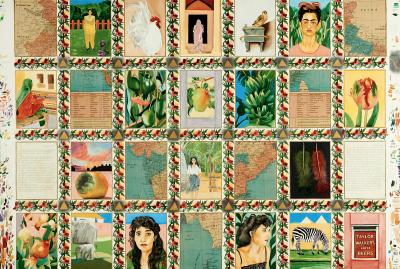

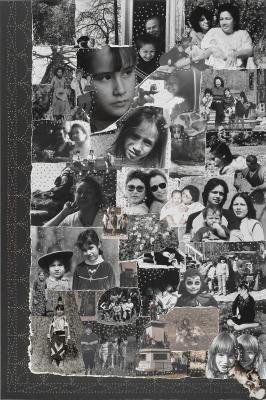

Today we think of chintz as a cotton printed with flowers in bold colours against a light, plain background, and we may associate it with England. But its roots go much deeper, to India. Originally hand-crafted in India, chintz in modern times was appropriated and industrially produced in European factories. Looping back into mainstream popularity every 30 to 50 years, chintz has always found its way into the worlds of fashion, design and art. We see this in the AGO’s exhibition Cassatt-McNicoll: Impressionists Between Worlds in Helen McNicoll’s paintings featuring floral-patterned chintz sofas:The Victorian Dress (1914) and Chintz Sofa (1913). Similarly, Mary Cassatt’s painting Portrait of Madame J (Young Woman in Black) (1883) also features a domestic interior with chintz-upholstered furniture.

So, what made chintz so popular in the 19th and 20th centuries and how did it stand the test of time? What did it symbolize? Further, what roles does chintz play today in art and fashion? To find out, we connected with Sarah Fee, Senior Curator of Global Fashion & Textiles (Asia and Africa) at the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) who wrote Cloth that Changed the World: The Art and Fashion of Indian Chintz, to learn more about the centuries-old history of the textile.

Foyer: Where did chintz originate? How is it traditionally made?

Fee: The term chintz itself is originally Hindi and hails from India. It means spotted or speckled. It’s an Indian term because the technique of printing cotton with bold colours itself comes from India. Before modern times, about 1860, it was very difficult to get cotton to take colour and pattern. However, thousands of years ago, artisans in India developed techniques to create brightly-coloured designs on cotton using special substances. With a brush or block, they applied these substances to the cloth surface which would then attract or repel dyes—indigo, turmeric, madder plants. That was how colour-patterned cotton dress and furnishing fabrics were made.

India exported vast quantities of its chintz painted and printed cottons to Africa and Asia for over a thousand years, adjusting designs and colour to suit every market. Europe was very late to the party. European chintz consumption really only began after 1500, when European East India companies began sailing to maritime Asia. They went in search of spices, but found that Indian chintz was more popular and profitable back in Europe, both as furnishing fabric and as dress. Merchants often commissioned designs, but Indian artisans loosely interpreted them, mixing florals and other motifs from both Asia and the West. Soon, European textile producers at home were trying to imitate chintz using Indian techniques. By 1770, Britain and France had mechanized production, and by 1820 Britain’s factory-made chintz replaced Indian hand-made chintz in global markets—including in India itself!—and put India’s artisans out of work. It’s no wonder that freedom fighters such as Mahatma Gandhi made rejecting imported printed English cottons to instead consume India’s own cotton textiles a cornerstone of independence movements from the 1910s.

Mordants, resists, and dyes could also be applied using carved wooden blocks. Here the printer is applying the mordant alum; after dyeing with the roots of certain plants, the printed areas will turn red. Photography by Sophena Kwon, Maiwa.

Foyer: What made chintz so popular and influential in the West, in the fashion and art world? What did it symbolize back in the 1800s to 1900s?

Fee: Everything about Indian chintz was novel in Europe. We have to remember that up until 1500, cotton cloth did not exist in the West. There was only linen and wool, which was much more difficult to colour, wear and wash. So cotton itself was a revolutionary fibre in many ways. And Indian chintz’s bright colours were unparalleled. India is home to potent dye plants for indigo blue and bright reds not found in the West.

Of course, design was also a huge part of it. India’s cotton painters and printers were able to continually invent and adapt new designs to appeal to consumers everywhere, from Thailand to Ethiopia. Europe developed its own tastes. Floral designs on a white ground are only one kind of chintz pattern, and a rather late one. The earliest Indian chintz made for Europe might show monkeys, mongoose, cobras and things people had never seen before. The Dutch preferred red or purple grounds. A popular chintz wall covering featured enormous flowering trees with scattered animals, combining Indian and European species. These designs were in many ways co-creations, and are often called Indo-European chintz.

But design changes over time as fashions change over time. In Britain by the mid-1770s, chintz goes from a very fussy, compact, and crowded design, to a very sparse, clean white ground with a more minimalist design of floral sprays or flower heads. It was probably tied in part to a middle-class way of showing hygiene, cleanliness and the ability to have white as a fabric. It was this pattern that was most imitated by European factories, and most popular with consumers. So by the late 19th century, the Indian origins of the textile had already been forgotten and was considered, instead, quintessentially European or quintessentially "British country house".

European-made chintz also has known cycles of fashion, essentially appearing and disappearing every 30 to 50 years. By the 1820s, it had gone out of fashion as an interior design and for dress in Europe. In the 1870s, it came back into fashion partly because of William Morris and the arts and crafts movement.

Foyer: The chintz sofa has appeared in the works of Impressionist painters like Helen McNicoll and Mary Cassatt. Can you give some insight as to why chintz became a common motif in artworks of that time? What did it symbolize and tell us about these artists?

Fee: By the late 1800s to early 1900s, English chintz meant many things to many different people. It was still fashionable for wealthy British interiors until the start of WWI, although it would wane soon thereafter with the new modern minimalist interiors. Chintz furnishing fabrics were fashionable from 1870 to 1900, so it’s not surprising to encounter them in domestic interior spaces, and so also in paintings of the time.

As a viewer looking at the chintz sofa paintings of Cassatt and McNicoll, I can't help but first notice all the white. The curtains are white, the clothing is white, and then you have these vivid floral sofas. I must wonder if the artists may have thought of bringing the garden, the exterior, inside. To make an interior garden. To me, it resonates with the idea expressed in the [AGO] exhibit of presenting women as dynamic subjects with rich interior lives, as they [these painters] chose to incorporate elements of outdoor landscapes to the indoors.

Actually, by the time of McNicoll’s works, chintz would have been on the downslide again in terms of popularity. So, it’s fascinating to see her focusing on it and directly naming the paintings after the textile. In my opinion, McNicoll’s own choice of chintz print could be part and parcel of her ongoing interrogation of female labour and creativity. Certainly, the bold, willful, colourful sofa print contrasts sharply with the anachronistic all-white Victorian dress in McNicoll’s painting of that name and supports a reading of seeking freedom from constraint.

Woman’s jacket. Textile made in coastal southeast India, for the Dutch market, eighteenth century. Cotton, hand-drawn, mordant-dyed, resist-dyed. Tailored and woven ribbon added in Europe. ROM 962.107.2

Foyer: Has chintz made a comeback since then?

Fee: Both Indian handcrafted chintz fabrics and Western factory-made chintz have known fashion cycles throughout the 19th, 20th centuries and even in the 21st. Every generation, it seems, rediscovers it. In the West, printed floral cottons went out of fashion in the early 1900s and then started creeping back in the 1940s and 1960s as Jackie Kennedy reintroduced them to interior design in the White House. Next, chintz was further built up as a desired textile with Laura Ashley, one of the many brands in the 60s to the 80s who made it popular again for middle-class furnishings. Fashion designer Bill Blass used interior designer Rose Cummings’ Cabbage Rose in his spring 1983 collection. The famous designer Mario Buatta, nicknamed the “The Prince of Chintz,” used the print extensively to bring English country house style to the United States. Chintz interiors also bleed into dress fashion, with Princess Diana and Nancy Reagan popularizing it. By the 80s, it was all about chintz again. I’m sure we all remember our flowered dresses from the 80s!

Of course what comes next is a backlash. It begins with IKEA. They ran one of the world's most successful ad campaigns in 1996 called Chuck Out Your Chintz. It was particularly aimed at the British and getting rid of what they called “fussy interior design.” The ads showed British housewives throwing floral lamps out their windows and running to IKEA for minimalist design. So in the 1990s to 2000s, chintz is out again and we're back to beige and white. But in 2018, it returns to become a huge fashion craze, back on the runways and as interior design. Maximalism was back again. H&M collaborated with the William Morris archives, to create a floral chintz line of fashion. Many famous interior designers were using it as well. Some see it specifically as nostalgia for the 80s, for Laura Ashley, and for yet others, it is about cottagecore. Usually a desire to evoke a perceived simpler, easier time. Even IKEA in 2017 reintroduced a chintz floral fabric for its armchairs!

In India too, for the last 20 years, Indian chintz – that is, hand printed or painted cottons -- has made a huge comeback. Some of it is exported to the west, to consumers seeking slow fashion or natural fibres and dyes. Much more of it is consumed locally, by local fashionistas and designers who value it for the same reasons, and also as a unique, heritage textile. If the number of India's cotton painters and printers had dangerously dropped by the 1960s, today there are hundreds of thriving ateliers and dedicated cotton print boutiques such as Anokhi.

Foyer: Are there any artists or designers that you feel have incorporated chintz into their work in interesting ways?

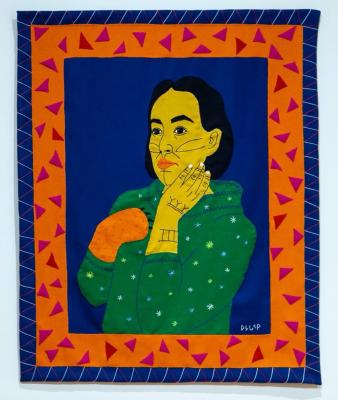

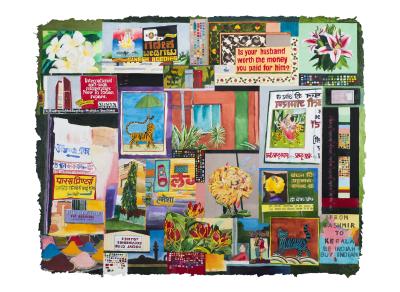

Fee: For me the most interesting work is coming from Africa and Asia, from artists working with printed cottons -- their patterns or techniques — to resurrect the Indian origins of the cloth, or explore the violence and appropriation that followed with European colonization and industrial imitation of local cloth.

In the U.S. and Europe, the Singh Twins presented several works in their exhibit Slaves of Fashion that speak to British and Dutch colonial violence and appropriation of indigo (the plant dye native to India that coloured chintz) and chintz fabrics.

Artist Meena Hasan paints details of chintz florals to visually “time travel” and to free patterns from the purely decorative. She features the mango tree (which is indigenous to South Asia) to emphasize the South Asian origins of the textile.

Besides works on canvas and paper, chintz patterns also became integral to English ceramics. The ceramicist Michelle Erickson interrogates themes of colonial violence, global commodities and empire with her 2006 Globular Chintz Teapot.

In India, the studio-based artist Ajit Kumar Das of Kolkata uses the hand painting and natural dye techniques of chintz to make contemporary paintings that explore esoteric and personal stories and imagery. Another artist, Renuka Reddy, based in Bangalore, explores and re-creates 18th-century Indo-European floral chintz designs in her works. In terms of fashion, all major Indian designers from Rajesh Pratap Singh to Ritu Kumar to Sabayasachi and 11.11/eleven eleven have in recent years brought out chintz (printed floral cotton) fashion lines. Nowadays, major lifestyle store Good Earth is also promoting natural dyes and hand-crafted chintz for fashion and décor.

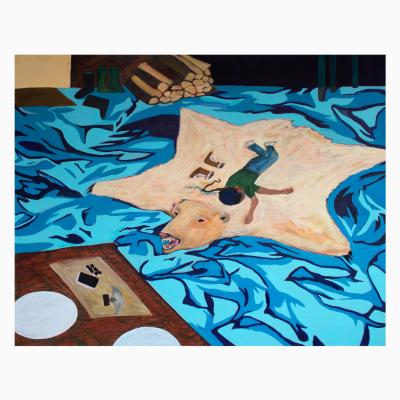

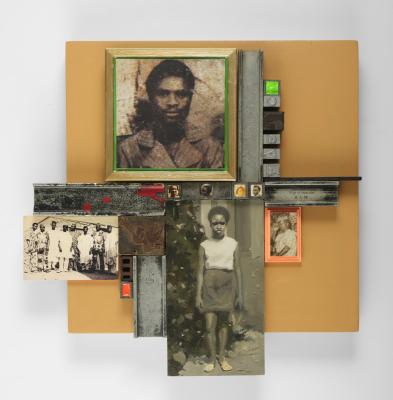

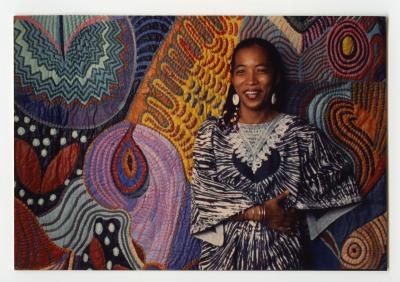

Far beyond Europe, Indian chintz inspired textile arts in Africa and Southeast Asia. It gave birth to the handmade cotton batiks of Indonesia. The designs of Indonesian batik, in turn, gave birth to the cloth we today call “Dutch wax” or “African prints”. Taking design direction from consumers in Africa, European factories in the early 1900s developed new patterns that combined Indonesian batik design with African aesthetics, creating a brightly patterned cotton still now worn across much of the continent. Today, numerous artists explore identity, colonial violence and globalization through these African prints—as sculpture or self-portrait photography or painting. Some of the better-known and most creative in my view include Yinka Shonibare, Hassan Hajjaj, Grace Ndiritu, and Omar Victor Diop.

Cassatt-McNicoll: Impressionists Between Worlds is on view now until September 4 in Sam and Ayala Zacks Pavillion, located on Level 2 at the AGO.